* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download WEIGHT CHANGE AMONG COLLEGE

Survey

Document related concepts

Body fat percentage wikipedia , lookup

Fat acceptance movement wikipedia , lookup

Human nutrition wikipedia , lookup

Waist–hip ratio wikipedia , lookup

Body mass index wikipedia , lookup

Overeaters Anonymous wikipedia , lookup

Gastric bypass surgery wikipedia , lookup

Abdominal obesity wikipedia , lookup

Diet-induced obesity model wikipedia , lookup

Food choice wikipedia , lookup

Obesity and the environment wikipedia , lookup

Obesity in the Middle East and North Africa wikipedia , lookup

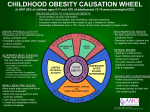

Childhood obesity wikipedia , lookup

Transcript