* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

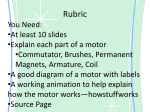

Download Design and Implementation of a Hybrid Electric Bike

Three-phase electric power wikipedia , lookup

Power inverter wikipedia , lookup

Transmission line loudspeaker wikipedia , lookup

Current source wikipedia , lookup

Stray voltage wikipedia , lookup

Electrical substation wikipedia , lookup

Brushless DC electric motor wikipedia , lookup

Electric machine wikipedia , lookup

Power engineering wikipedia , lookup

Electrification wikipedia , lookup

History of electric power transmission wikipedia , lookup

Mains electricity wikipedia , lookup

Voltage optimisation wikipedia , lookup

Switched-mode power supply wikipedia , lookup

Dynamometer wikipedia , lookup

Electric motor wikipedia , lookup

Power MOSFET wikipedia , lookup

Pulse-width modulation wikipedia , lookup

Opto-isolator wikipedia , lookup

Buck converter wikipedia , lookup

Alternating current wikipedia , lookup

Induction motor wikipedia , lookup

Brushed DC electric motor wikipedia , lookup