* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download COMMENTARY On the Diversity of Nature and the Nature of Diversity

Community fingerprinting wikipedia , lookup

Biogeography wikipedia , lookup

Molecular ecology wikipedia , lookup

Conservation psychology wikipedia , lookup

Theoretical ecology wikipedia , lookup

Restoration ecology wikipedia , lookup

Animal genetic resources for food and agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Ecological fitting wikipedia , lookup

Biological Dynamics of Forest Fragments Project wikipedia , lookup

Fauna of Africa wikipedia , lookup

Natural environment wikipedia , lookup

Conservation biology wikipedia , lookup

Tropical Andes wikipedia , lookup

Reconciliation ecology wikipedia , lookup

Biodiversity action plan wikipedia , lookup

Habitat conservation wikipedia , lookup

Biodiversity wikipedia , lookup

Latitudinal gradients in species diversity wikipedia , lookup

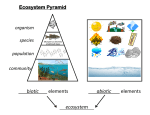

COMMENTARY On the Diversity of Nature and the Nature of Diversity I met a traveller from an antique land Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone Stand in the desert ... Near them, on the sand, Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whosefrown, And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command; Tellthat itssculptor well thosepassions read Which yet survive, ~tamped on these lifeless things, The hand that mocked them, and the heart thatfed: And on thepedestal these words appear: 'My name is Ozymandias, king of kings: Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!" Nothing beside remains. Round the decay Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare The lone and level sands stretchfar away. -"Ozymandias" Percy Bysshe Shelley LLoYD KNUTSON D IVERSITYwas the theme of the 1988 meeting of the Entomological Society of America, chosen to link with themes of other recent meetings: Habitat in 1986 and Evolution in 1987.It was to express an essential aspect of insects and related organisms, of entomology, and of the Entomological Society of America. I wish to relate entomology to the broad issue of the preservation of biotic diversity and to explore some aspects of entomology and ESAfor which diversity may be of value. My intention is to present a message of challenge, one of shared responsibility. My message contains several somewhat related aspects: the general issue of the preservation of diversity, areas of entomology that are related to issues of diversity, aspects of ESA for which emphasis on diversity is of benefit to the science and our membership, and a call for action on specific items. Preservation of Diversity When, in the 1960s, we saw the first pictures of Earth from space, and when, in 1969, we saw man's first step in the dead 0013-8754/89/0007-0011'02.00/0 dust of the barren desert of the moon, we saw the uniqueness and vitality of our blue and green globe-and, we hope, we realized its fragility. Yet the very ability to fly to the moon and to see Earth from space, shows us as tragic figures. We stand kneedeep in environmental sewage, in a worldwide shambles of our own making, and we sling rockets at the stars. Meanwhile, an irretrievable legacy of diversity is being lost. In 1986, the Smithsonian Institution and the National Academy of Sciences jointly sponsored a symposium on biodiversity, at which such entomologists as Paul R. Ehrlich, Thomas Eisner, Charles D. Michener, and E. O. Wilson characterized the insults-the threats-to our global ecosystem as second in importance only to the threat of thermonuclear destruction. The preservation of biotic diversity, according to many, is the issue that stands at the crossroads of the future of the human race. These statements are not mere rhetoric. They are based on solid knowledge of global warming; disruption of the ozone layer; air, water, and soil pollution; acid rain and acid soils; degradation in groundwater quality; erosion; the pressure of energy demands-whether from the growth in electricity production in the industrialized na- ~ ]989 Entomological Society of America tions or deforestation in developing countries; depletion of natural resources; problems of hazardous waste disposal; and homogenization of agricultural and natural ecosystems by aggressive invading species. At the root of these problems is the primary challenge to human survival: exponential increases in population that cause overproduction and overuse. The problem with humans and the biosphere is that there are too many humans and not enough biosphere. We humans stand at the apex of the pyramid of life, but we are systematically removing the stones at the base. The most invasive, "weedy" species of all time, we appear to be on a suicidal mission to destroy the very life support system on which our future depends. Why? Significantly, because we and our leaders do not appreciate the extent of biotic diversity, do not understand very well the life support processes that depend on diversity, and thus do not underKNUTSON is director of the USDA-ARS Biological Control of Weeds Laboratory in Rome (U.S. Embassy-Agriculture, APO New York, N.Y. 09794). This commentary is adapted from his presidential address before the 1988 ESA Annual Meeting in Louisville, Ky. LLOYD 7 stand the value of maintaining a high level of natural diversity. Blinded by ignorance, we poorly protect and poorly manage biotic diversity, the thin veneer of fragile, complex ecosystems that cover the "superorganism," Earth. As we inappropriately use a fraction of diversity we are exterminating its larger part. And curiously, we who are the cause of biotic chaos appear to be an endangered species. I agree with the outlook of the founders of the Society of Conservation Biology,who stated in forming that mission-oriented, interdisciplinary scientific society that it is implicit that nature can be preserved. What value would there be in studying our own destruction unless we could avoid it? But there is little time, perhaps only a few decades, in which to rescue ourselves from environmental disaster. Time does not allow the luxury of compiling masses of data; even the lowest estimates of human-induced extinction rates are sufficient for decision making. The need for information and its management is to find ways to solve the problem of biotic diversity Some believe that the great environmental struggles will be won or lost in the 1990s.The clock is ticking. Transfer of scientific information to the public and its use in legislation is crucial to the process of dealing with the biodiversity crisis, and ESAhas many roles to play in that process. The essence of these roles is expressed in the theme of our centennial: "Entomology Serving Society" One important role, one opportunity, is to carry out research and provide information on diversity-the diversity of insects and related organisms. There is a long tradition in ESA of interest in biotic diversity C. V.Riley, first president of the American Association of Economic Entomologists, founded the National Insect Collection and started the first, but short-lived, Bureau of Biological Survey Other illustrations can be found in the work of such writers as Howard Evans (Life on a Little-Known Planet) and E. O. Wilson (The Little Things That Run the World). Entomology and agriculture are closely linked. Although agroecosystems displace natural ecosystems, there are strong proponents of biotic diversity who work in agriculture, from growers to policy makers. One important piece of legislation, the Food Security Act of 1985, included major provisions related to habitat protection and restoration: "Sodbuster," "Swamp buster," the Conservation Reserve, conservation setasides, and easement provisions. This bill and others are solid evidence of public concern translated into legislative action. Other examples of action taken include the state, federal, and private edifice of land manage8 ment and environmental agencies and programs; the reauthorization and strengthening of the Endangered Species Act of 1973; the 191 million acres in our system of national parks and grasslands; the 90 million acres in the Fish and Wildlife Service refuge system; the 3.5 million acres preserved by the Nature Conservancy and its cooperators in the past four decades; the U.S.Agency for International Development's consideration of environmental impact in planning its programs; and a House Science Committee report stressing biological diversity and conservation biology in the National Science Foundation Authorization Act for 1989. However, the scope ofthese efforts is limited. The Endangered Species Act, for example, protects critical habitats, primarily on u.s. federal property. Of the 485 species listed as endangered or threatened in the United States, nearly half are plants; only 15 are insects. Yet the total of U.S. flora and fauna is at least one-half million species, of which only 200,000 have been described. Perhaps the most significant new step that is intended to go beyond the current U.S. ecological safety net is the National Biological Diversity, Conservation, and Environmental Research Act, which was introduced by a bipartisan group of more than 80 sponsors to the House of Representatives in the spring of 1988.Although some agency officials consider this act a duplication of existing legislation, its proponents emphasize that it is the proper purview of the federal government to evaluate the long-term effects of individual policies. A more limited bill was planned for Senate introduction. The House bill would establish the conservation of biological diversity as a national goal. It also would require a federal program for maintaining and restoring biological diversity in the United States, require that biological diversity impact be included in environmental impact assessments and statements, and establish a national center for biological diversity to improve knowledge of biological resources and ways they can be managed to protect diversity A few entomologists, notably K. C. Kim and Michael Kosztarab, have been directly involved in discussions of the legislation. 1Woof our affiliated societies, the American Institute of Biological Sciences (AlBS) and the Association of Systematics Collections (ASC), have been active in keeping scientists and the public informed about the resolution and in providing information and testimony to Congress. The overwhelming diversity of insectsin number but also in biology, life form, habitats exploited, and distribution-has begun to enter into these discussions. Although species with fur, feathers, or leaves often hold center stage with the public, there is a growing awareness of the need to conserve all forms of life. Of course, the value of high-profile species, such as pandas, elephants, and whales, in conferring protection on the less visible species occurring with them is being recognized. But it is for this identity problem that I support ESA's candidate for a national insect, and I personally prefer a creature recognized for its beauty, the monarch butterfly, to one known for its industry, the honey bee. In emphasizing the problem With biotic diversity in the United States, I do not mean to neglect other more serious situations. The preservation of the tropics, which harbor about 60% of the Earth's flora and fauna on just 6% of the planet's surface, is critical. The rate of extinction in the tropics is a horrifying 0.7% annually, a result of the destruction of 25,000 square miles a year. Apart from the problems of social distress that will result from tropical destruction, the well being of the rest of the globe is at stake. An International approach to the problem is essential to preserving biological diversity. Rep. Claudine Schneider (RR.I.), who was coauthor of the biodiversity bill with Rep. James H. Scheuer (D-N.Y.), has stated that "The unchecked loss of biological diversity anywhere in the world threatens all of us." But in testifying for ASC about the act, malacologist George Davis noted that the United States is "where we have the greatest ability to act, the greatest self-interest, the greatest know-how, and indeed, the greatest responsibility" Ethics is becoming a significant part of the issue. Philosopher Bryan Norton points out in The Preservation of Species-The Value of Biological Diversity that "The problem is, on the deepest level, not scientific but perceptual and attitudinaL" E. O. Wilson writes in the introduction to the proceedings of the Smithsonian-National Academy of Sciences biodiversity symposium that "In the end, I suspect it will all come down to a decision of ethics." In the same volume, Paul R. Ehrlich considers how it is that the analysis of scientific studies only points toward our need to come to almost a religious belief in the moral necessity of preserving diversity David Challinor, then assistant secretary for research at the Smithsonian, notes in the book's epilogue that "World leaders, who must make hard economic choices, may be so overwhelmed by more acute problems that they may not choose to invest in the security of humanity by perpetuating biological diversity." He concludes that the solution depends on the collective behavior and perception of people toward their habitat. BUll.ETIN OF THE ESA loss in the interest in observation, in oldfashioned natural history? How many of us will take time to watch a caterpillar crawl around for hours searching for its special, cryptic pupation site, so that pupae can be collected en masse as needed for biological control studies? We have learned to expect the unexpected of insects-blood-sucking moths; snail-killing flies; larvae that live in hot springs, arctic waters, petroleum pools, or salt lakes. Although much remains to be learned about economically important species, concentration of research on a minute and atypical segment of insect life, the "pests," gives a biased picture of ecological relationships. To balance our preoccupation with destructive agents, we would do well to look at the world from the insect point of view, as exemplified in the studies of Clifford Berg, Benjamin A. Foote, Richard D. Goeden, James L. Krysan, Robert W.Matthews, Carl W.Rettenmeyer, George B. Vogt, Robert F.Whitcomb, and Thomas K. Wood, among others. We cannot gain a complete understanding of pollination, the effect of colonizing species, parasitism, or predation unless we study important noneconomic groups. How we approach research on or management of pest or beneficial insects depends in part on our general understanding of insect biology. Insects are so many and so diverse that we can never hope to have an even sample of knowledge across tions today have a practical urgency for conservation planners and resource managers. Many of these questions can best be pursued by the study of insects and related organisms. The array of questions about immigrant organisms, the exotic species accidentally or purposefully established in new areas, is of interest both to applied and to basic entomology. Long of interest to entomologists, the subject was brought to the fore in Reece I. Sailer's 1977 ESApresidential address, "Our Immigrant Insect Fauna." Immigrant species are significant from practical and theoretical points of view as pests; as beneficial species (especially as natural enemies of introduced pests and as pollinators); as noneconomic species that affect native, noneconomic plants and animals; and as prime subjects for the study of microevolutionary and biogeographical processes. Despite the importance of immigrant species and the fact that about 1,800 known immigrant species make up a small portion (perhaps 2%) of the North American fauna, it is surprising that information on their presence, geographic origin, adventive distribution, hosts, and prey is limited. An important element in the diversity of insect fauna, in the rest of the world as well as in North America, is inadequately known for economic and scientific purposes. ESA members E. Richard Hoebecke, Thomas). Henry, John D. Lattin, A. G. ogical products will fit into our ecosystems the class. We will never know the biologies Wheeler, Jr., Donald R. Whitehead, and oth- in environmentally sound ways. The area that deals most directly with diversity (and the one most threatened with extinction itself) is systematics, which, as a legitimate pursuit in and of itself, provides the framework for relating the diverse data of evolutionary biology. Its classifications give critically important predictive information. Systematics is not simply a means for managing the inventory of biotic diversity or a handmaiden to biological control, plant quarantine, ecology, or other areas. Without the effort and partnership of systematists, conservationists would not know what to conserve, and ecologists could not understand the dynamics of the ecosystems to be saved. Unfortunately, the needs and opportunities described for systematics by Curtis W. Sabrosky in his 1969 ESA presidential address remain largely unfulfilled. And Thomas Lovejoy,Smithsonian assistant secretary for external affairs, notes that entomologists "seem strangely unstirred as a group by the biological diversity problem." Knowledge of the diversity of insect behavior is, like knowledge of systematics, a basic and neglected area of study that is important to other areas. We are making great advances in using modern technology to analyze insect behavior, but is there some of many species and genera of some families because of the lack of time and resources and because we are driving some to extinction. The importance of diversity in ecological study was encapsulated by Robert M. May in "The Search for Patterns in the Balance of Nature: Advances and Retreats," which was published in the journal Ecology in 1986: Understanding the essentials of how species originate was the most important intellectual achievement of the 19th century. It seems to me that the next step-the largely unanswered question for the 20th century (and maybe the 21st)-is to understand how many species there are. The overall question ... is composed of a mosaic of subsidiary questions: what factors determine the number of species we expect to find in a given patch, or on a continent, or on the globe? How is the number of species in a given region likely to be affected by particular kinds of natural or human perturbation? ... Such questions have the same intellectual fascination and importance as questions about the forces binding nuclei or the large-scale structure of the universe. More than this . . . the ques- ers are contributing to this area. Although I recognize that insect genetics, physiology, pest management-in fact all aspects of entomology-interrelate with issues of diversity, there is just one more focal point I wish to discuss. Biological control is an indicator of the health of our science and a developing area that should be a significant part of ESA's future. Use of the diversity of nature to correct accidental pest introductions and to improve the health of our natural and artificial ecosystems is the objective of biological control. Thus, it has a natural link to those potent issues in natural resource management: resistance, residues, resurgence, and groundwater quality, which likely will become increasingly important in driving funding for many aspects of entomology. Especially in biological control there is opportunity for ESAto contribute in the international arena. Entomology and Diversity Several areas of entomology have especially important relationships to issues of biotic diversity. They are also examples of the diversity of the science and of ESA.The "big science" of molecular biology and the "small science" of whole-organism biology reflect the diversity of science, but they also could exemplify the unity of science. Aspects of entomology are in both sciences. The conflict between them is primarily a contest for funding that stands in the way of fruilful integration. Certainly, wholeorganism biology has not been adequately supported recently, and there is the fear that such megaprojects as genome-mapping studies will drain resources further. Are our universities, as Robert Jenkins of the Nature Conservancy has written, "Hell-bent on turning their departments of biology into biotechnology departments"? Are we missing an important opportunity to form useful links between diverse approaches and interests? Entomology and other sciences can be made stronger by incorporating these unifying threads. As an integral part of biotechnology, we need the predictive powers of systematics to guide our search for new sources of genetic material. We need classical biologists to show us what diverse organisms have to offer for directed mutation. And we need the ecologists to show us how biotechnol- WINTER 1989 Emphasis on Diversity Benefits Science and Membership With 8,300 members, ESA is the largest entomological society in the world, surpassing the Entomological Society of China, which has 7,000 members. Most ESA members (7,300) are U.S. citizens, although 9 about 400 of them work overseas. We have about 400 Canadian and Mexican members, and about 600 members in other countries. Student membership has grown over the past decade to the current total of about 1,200. There are only about 200 foreign student members, however, most of them are studying in the United States. The size and diversity of membership provides ESAwith some opportunities and responsibilities, particularly internationally. Yet ESAdoes not have a strong international posture. Other smaller societies have placed more emphasis on international activities. The American Phytopathological Society, for example, recently established an office in international affairs, which has a specified budget. The evolution of our longterm Special Committee on International Affairs, currently chaired pies of our recognition of this interest. Following the suggestion of several members and a committee review, the Governing Board has approved a Youth Member category. Our organization has had a relatively poor record with regard to the diversity of its relationships with other organizations. In recent years we have severed our ties with some groups. I believe, however, that the interest of much of ESA'smembership is changing. We need to reconsider these relationships-not entirely in the sense of how much money we can save by not being affiliated, but in the sense of what the membership loses by not having such ties. These relationships are not bureaucratic considerations. They are important to the overall membership. The diversity by Carrol O. Calk- ins, into a standing committee would be an important step forward. Entomology has a special fascination for many young people. Our Committee on Youth Science Development, chaired by Rick L.Brandenberg; the target audience for our film "Discover Entomology"; and participation in science fairs are some exam- of ESA's journals is limited. Our science is much broader than our few publication outlets reflect. Journals started by other publishers on other areas-insect behavior, physiology, and morphologyshould have been started by ESA.Our purchase of the journal of Medical Entomology was a step in the right direction. We can expect to lose authors, editors, and even members if we do not pursue the possibility of new journals. We need a publication of broad interest, and I hope that the Bulletin in its reincarnation as the American Entomologist, will move quickly in that direction. Call for Action I call on each of us as members to consider some general and specific opportunities and needs. Although some of them relate to the broad issues of diversity, the following is partly a summary of our activities in 1988. We have made progress on a few. I suggest that we continue to support AIBS, ASC, and other organizations that provide ESAwith a link to broad issues such. as biotic diversity. We should also be build- ing new connections with other natural resource organizations, including the Council for Agricultural Science and 1echnology. We should take a hard look at the nature of our meetings and how effectively they relate entomology to the rest of the world. We should consider the use of small, critical issues seminars as a way to analyze where ento- Introducing the LAI-2000 Plant Canopy Analyzer • Non-destructive determination of Leaf Area Index (LAI) • Direct readout of Leaf Area Index in the field • Rapid Measurements • Measurements under all sky conditions 10 The new LAI-2000 Plant Canopy Analyzer estimates Leaf Area Index (LA I) and Mean Tip (inclination) Angle (MTA) for a vegetative canopy from measurements of light interception. Canopy interceptance is calculated from measurements of the sky made above and below the canopy with a "fisheve" OPtical sensor. Measurements are made u ing diffuse sky radiation rather than direct solar beam radiation. The advantage of this technique are: o Mea urements under any sky condition (cloudy is best) o Immediate results (no waiting for sun angle to change) o Works at any location, such as high latitudes in the winter o Suitable for any size canopy (e.g. gras, forest, etc.) The optical sensor measures light interception at five azimuth angles simultaneously by using a fisheye lens system to project a hemispheric image of the plant canopy (or sky) onto five separate silicon detectors arranged in concentric rings. The lens system causes each detector to see a different portion of the sky. Since the optical sensor sees 3600 of azimuth, LAI estimates are based on a large sample of the canopy. All calculations are performed by the LAI-2000 control unit for onsite evaluation of your data. For more information call us at (402) 467-3576. Or write: U-COR, Box 4425, Lincoln, Nebraska 68504, USA. TWX: 910-621-8116 FAX: 402-467-2819. BULLETIN OF THE ESA mology should be more involved, and as a mechanism for building bridges. We should use these seminars to come to grips with support for the most threatened aspects of entomology-systematics, international cooperation in biological control, and others. We should shed our conservative attitude about publications and go ahead with a journal on biological control, a symposium series, and establish our magazine as the premier news outlet for our science. We should employ a full-time entomologist to assist the administrative staff with technical information, to build those bridges that require biopolitical expertise, and to lead grant-supported projects such as an information system on immigrant arthropods, an international directory of insect identification, and others. We should establish an international programs office, develop international contacts, and make a special effort to expand the scope of our thinking on such international issues as biological diversity. We should develop meaningful youth and amateur categories that provide substantial services to their constituents. We should establish a newsletter that will cover important state and federal programs and policy actions. We should support the inventorying of the insect fauna of North America, improve our relations with industry and the public, and encourage the role of the American Registry of Professional Entomologists therein. We need to develop a continuing-education program in concert with branch, section, and registry interests. We should engage in service to entomologists from a not-forprofit perspective, and we should continue in other appropriate ways to promote the value of our discipline and profession. The strength of our planet lies in the diversity of nature; the strength of ESAlies in the nature of its diversity. Dedication to preserving diversity is the only acceptable future we have. • Acknowledgment I thank the following for their comments on this manuscript and the notes for the oral pres- Environlllental Control FrOlll Percival Have control of the environment with a biological, insect rearing, dew, or plant growth chamber from Percival. Whether you need a table model or a giant walk-in, Percival has the knowledge, experience, and quality product line to meet your specific needs. Or, Percival will prepare a recommendation to fit your requirements. Write today for more information and the complete Percival catalog or call collect 515/432-6501. WINTER 1989 entation on which it is based: R.V.Carr, M. Dourojeanni, P.H. Dunn, T.L. Erwin, D. Feir, K. C. Kim, D. R. Kincaid, M. Kosztarab, M. Ma, R.j. McGinley,J.J. Menn, D. R. Miller, B. C. Pass, P.C. Quimby, Jr., R.L. Ridgway, and R. Villett. The following supplied photographs for use in the oral presentation: M. Cristofaro, R. E Denno, D. Dussourd, L. Fornasari, R. D. Gordon, A. S. Menke, D. R. Miller,J. Plaskowitz, A.Y.Rossman, and E C. Thompson. Suggested Reading Kim, K C. & L. Knutson [eds.]. 1986. Foundations for a national biological survey. Association of SystematiCS Collections, Lawrence, Kans. May, R. M. 1986. The search for patterns in the balance of nature: advances and retreats. Ecology 67: 1l15-1126. Norton, B. G. [ed.]. 1986. The preservation of species. The value of biological diversity. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. Wilson, E. O. 1987. The little things that run the world (The importance and conservation of invertebrates). Consen': BioI. 1: 344-346. Wilson, E. O. [ed.] 1988. Biodiversity. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C. Since 1886 Percival Manufacturina Company P.O. Box 249 • 1805 East Fourth Street Boone, Iowa 50036 Th nGlM 10 r~ for W'l'wlk BioIorlcal Incuba&ors, Ins«t ~C1rin, ChamMs, Dew Chambn-. C1ndPlcant Growth Chamber •. 11