* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download to read the full Gender Dysphoria Article.

Gender and development wikipedia , lookup

Transfeminism wikipedia , lookup

Blanchard's transsexualism typology wikipedia , lookup

Prenatal hormones and sexual orientation wikipedia , lookup

Gender inequality wikipedia , lookup

Gender role wikipedia , lookup

Sex differences in humans wikipedia , lookup

Causes of transsexuality wikipedia , lookup

Michael Messner wikipedia , lookup

Judith Butler wikipedia , lookup

Gender and security sector reform wikipedia , lookup

Gender Inequality Index wikipedia , lookup

Feminism (international relations) wikipedia , lookup

Social construction of gender wikipedia , lookup

Gender apartheid wikipedia , lookup

Gender roles in non-heterosexual communities wikipedia , lookup

Special measures for gender equality in the United Nations wikipedia , lookup

Judith Lorber wikipedia , lookup

Sex and gender distinction wikipedia , lookup

Gender roles in childhood wikipedia , lookup

Third gender wikipedia , lookup

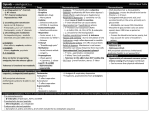

GENDER DYSPHORIA (Gender Identity Disorder) DIAGNOSIS The diagnosis of gender dysphoria (formerly gender identity disorder) emphasizes the incongruence between one's perceived gender and one’s anatomical sex particularly in older children, adolescents, and adults. In all ages a strong desire to be the other gender must be present and will reduce the possibility of over-diagnosing individuals who have extreme gender-variant behavior. Although some advocate the removal of “transgendered” conditions from diagnostic nomenclature, gender identity disorders are recognized disorders because they almost always cause significant distress, or as one patient said, “How would you like to go through life as a woman trapped in a man’s body?” Dysphoria rather than disorder captures how the incongruence feels. With gender dysphoria there exists a determination and motivation for change but conversely a lack of flexibility and willingness to entertain other options. That rigidity may interfere with treatment and the most satisfactory resolution. Increased age, duration of cross-gender behaviors, and resistance to change these behaviors are more likely to be associated with real gender dysphorias. Formerly called “transsexualism” in adult cases, gender dysphoria is such a persistent feeling of severe discomfort with one’s own anatomical sex, that there is a strong wish to be rid of one’s genitals, and wish to live as the opposite sex. TABLE 1 Diagnostic Criteria for Childhood Gender Identity Disorder (Gender Dysphoria) A. An intense and persistent cross-gender identification as manifest by the following (DSM-5 requires at least six): 1. the pervasive and persistent desire to be (or insistence that he or she is of) the opposite sex to that assignedepeatedly stated desire to be, or insistence that he or she is, the other sex 2. an intense rejection of the attire of the assigned gender and persistent preoccupation with the dress of the opposite gender 3. an intense rejection of the attributes and behavior (roles) of the assigned gender 4. a very strong desire to participate with the games, toys and pastimes stereotypically of the other gender 5. preferred playmates are of the opposite gender 6. an intense rejection of participation with the games, toys, and pastimes stereotypically of the same gender 7. repudiation of the anatomical structures specific to their own gender 8. a strong desire for the sexual anatomy of the other gender In adolescents and adults, the disturbance is manifested by symptoms such as a stated desire to be the other sex, frequent passing as the other sex, desire to live or be treated as the other sex, or the conviction that one has the typical feelings and reactions of the other sex. B. Persistent and intense distress about ones assigned gender or significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational or other important areas of functioning. Note. Adapted from ICD-10 (pp. 168-170) and DSM-5 (pp. 452-459) EPIDEMIOLOGY Gender dysphoria is rare but may be increasing, with an estimated prevalence among men of 1 in 25,000; among women, 1 in 100,000. Heightened awareness and increased openness in today's society has resulted in more referrals for gender dysphoria. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS Those with gender dysphoria usually, but not always, cross-dress to be in accord with their own gender identity. The patient’s family members typically recollect that as a child he wanted to be a she, or vice versa, even as early as 3 years old. While growing up, these children often experience correction, criticism, ostracism, and/or marginalization by peers and some relatives. These interpersonal difficulties, combined with the person’s own strong and disturbing intrapsychic cross-gender conflicts, result in high rates of oppositional and antisocial behavior, self-mutilation (frequently of the genitals), attempted suicide, and completed suicide. If a gender non-conforming youth experiences erotic pleasure and sexual arousal from engaging in cross-gender role behaviors, the diagnosis would more likely be a paraphilia (transvestitic fetish). In adolescents it is difficult to know whether this is a permanent situation or just an experimental phase in someone who will never seek gender reassignment. The gender dysphoria may reflect an individual’s lack of acceptance of homosexuality. Also, there are those who believe that cross-gender behavior is a normal developmental pathway to homosexuality. However, gender non-conformity is clearly not a precondition of homosexuality and does not necessarily lead to the same. In rare cases of gender dysphoria there is a wish for genital ablation in persons who preferred to be sexless but have no cross gender identity for example in a male to eunuch identity disorder in males who seek castration voluntarily without wanting to acquire the female sex characteristics. Similarly there are teens who attempt to integrate masculine and feminine aspects of the self and adopt an androgynous or gender queer form of expression. This may signify incomplete gender identity development. With a history of sexual abuse such a wish may be an avoidance of traumatic reminders. Post-traumatic gender dysphoria and associated gender variant behaviors may be a repetition compulsion of sexual abuse to relieve the anxiety associated with the anticipation (likelihood) of future trauma. Family stress whether a major change, loss, or some other trauma may cause brief periods of cross-gendered behaviors. To make the diagnosis of gender dysphoria, the intrapsychic gender conflict must not be the product of psychosis. Psychotic delusions may be present in mood disorders (mania or depression), delusional disorders, and schizophrenia. With a psychotic delusion, an individual may truly believe he or she is a member of the other sex, but an individual with a gender dysphoria strongly feels like a member of the other sex rather than believing it is factually true. Neurologic impairments across a spectrum of parietal lobe dysfunction could cause a variety of syndromes leading to dissatisfaction with one's physical body. Comorbid psychiatric problems may be a driving factor of gender dysphoria and desire for gender reassignment. One study revealed over half of GD children met criteria for at least one other psychiatric diagnosis. Perhaps 30% have an anxiety disorder. GD is also significantly associated with measures of parental psychopathology. Prenatal sex hormones (androgen exposure) may affect gender role behavior and sexual orientation in adulthood. Those individuals with ambiguous genitalia have a higher rate of gender dysphoria and patient initiated gender change than the general population. Such intersex conditions are most often caused by congenital adrenal hyperplasia or 5-alphareductase deficiency. See Guevote note in references. It is important to consider an underlying diagnosis of Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD) when encountering patients with gender dysphoria. Autistic spectrum disorders are present in 10% of individuals with gender dysphoria. This association is possibly explained by the propensity for obsessions and restricted interests. When individuals with ASD realize their uniqueness and differences compared to others, they may develop confusion of identity which could be exhibited as gender dysphoria. Some autistic individuals assert gender dysphoria symptoms in response to social isolation at school. Many of the clinical symptoms related to gender dysphoria might be explained by the cognitive characteristics and psychopathology of ASD. Although the comorbid psychopathology may be the result rather than the underlying problem of gender dysphoria, being transgender may also be sought as a solution to non-gender problems. Even experienced interdisciplinary teams find it is more complicated to accurately diagnose gender dysphoria in youth who are not functioning well in multiple domains. The validity of the evaluation in the face of self-presentation biases can be improved by interviewing multiple informants and by employing various methods to collect accurate clinical data. ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS Gender identity development is complex and the mechanism of geneenvironment interactions of mechanisms poorly understood with unclear outcomes. There are no associations with systemic hormone levels in adolescents and adults and GD or homosexuality. It has been hypothesized that prenatal androgen exposure promotes the development of attraction to females whereas insensitivity or lack of exposure to androgens leads to male attraction. Antibodies to testosterone from previous pregnancies with a male fetus, may lead to incomplete androgenation of the brain (consistent with the later birth order and more older male siblings). Also androgen insufficiency may occur with fetal stress. There are epigenetic explanations for same-sex partner preference, ambiguous genitalia, and transgender identity. Homosexuality does occur more frequently in families but no studies implicate a specific gene. Epigenetics is the study of heritable changes in gene expression caused by mechanisms other than the underlying DNA sequence. DNA methylation and histone modification do not alter the underlying nulceotide sequence but may persist for multiple cell divisions and are sometimes passed to the next generation. These epi-marks may regulate the expression of certain genes involving androgen production or response to androgens during fetal development. Sex-specific epi-marks produced early in embryogenesis may protect each sex from the substantial natural variation in testosterone that occurs later in fetal development i.e. girl fetuses are not masculinized even under high testosterone conditions and boy fetuses are still masculinized even under low testosterone conditions. However, if these same epi-marks are transmitted to the next generation from fathers to daughters or mothers to sons they would cause the reverse effects i.e. masculinized girls and feminized boys. Father absence may contribute to GD. Mother’s of boys with GD have high levels of emotional involvement and lower criticism. Mother’s anxiety about violence from men, poor management of stress, and ambivalent or hostile relationships with the fathers could lead to parenting that promotes cross-gender behavior in sons. Sons may be anxious about maternal withdrawal and abandonment. There may be a lack of parental discouragement of cross-sex behaviors. The concept of what is male or female in most societies is deeply ingrained in culture and largely dichotomous. There are individual variations in maleness or femaleness that challenge this dichotomy and as with many of our diagnostic categories the suggestion of a spectrum. Over time society can accept these individual variations. Extreme deviations from the norm are not by themselves pathologic but can lead to psychopathology (functional impairment). Substantial and unusual variation (outside the norm) in maleness or femaleness in behavior or identity is generally designated as cross gender, gender variant, gender atypical, gender non-conforming youth, or transgender. Gender nonconformity is not always accompanied by discordant gender identity. In the societal context these variations may lead to gender dysphoria. A desire to become a girl may have been an effort to avoid the bullying from male peers or greater identification with non-masculine traits. It may be a result of a life-long avoidance of exploration because of an anxious temperament (association of less risk-taking and strong attachment to the female gender). Also negative feelings about self may lead to gender dysphoria as an effort to cope with these feelings. If there was a history of abuse by a male perpetrator, the cross-gender identification may be post-traumatic avoidance as opposed to identification with the aggressor. DEVELOPMENT OF GENDER IDENTITY Gender constancy is established between the ages of two and seven years when the child is able to discriminate different gender roles and identifies accordingly. Children learn about boys or girls from authority figures and from social cues and they apply this knowledge to themselves. As the child matures he or she becomes increasingly motivated to observe, incorporate, and respect gender roles. Although the idea of gender spectrum and gender fluidity has merit, it is easier for most children to have some clear sense of gender consistent with being either a boy or girl because our culture depends on gender to explain sexuality, society, and self. By two years of age parents begin to notice gender deviant behaviors such as feminine interests in their boys. At this age children may have idiosyncratic ideas of what it means to be a boy or girl. By the time they enter preschool they have highly conventional, concrete, and rigid notions of boy versus girl behaviors. These gender classifications may generate confusion in someone not interested in the activities typical of other kids with the same anatomical sex. He or she does not realize that there are different kinds of boys or girls who prefer things of the opposite gender because they are uncommon. It is common for the expression of gender variant behavior to decrease later in childhood around age 9 or 10 years although it may emerge again during adolescence. In essence the diagnosis of gender dysphoria may represent a medical accommodation of a social prejudice, where the distress and dysfunction are the result of that prejudice. Gender dysphoria theoretically would abate with more acceptance of androgyny versus the current societal preference for a rigid gender dichotomy. The vast majority of pre-pubertal gender dysphoric children do not become transgender in adolescence or adulthood. Although at least 80% of childhood GD desists by adulthood, GD rarely desists after the onset of puberty. In fact, when GD persists into adolescence, puberty is often associated with a worsening of dysphoria and distress. Gender dysphoric girls referred in childhood are less likely to remit than boys. Both gender nonconformity and gender dysphoria are believed by some to be developmentally related to homosexuality. Adolescents with gender dysphoria may vastly differ in their ability to handle the complexities and adversities that often accompany gender variance. Some have such intense distress that they expect clinicians to immediately provide them with hormones and gender reassignment surgery as quickly as possible. Others are simply trying to find ways to live with these feelings of confusion or some unease. The gender dysphoria may have started long before puberty or be more recent. The environment can be accepting and supporting or rejecting. These individuals may present with a broad range of coexisting psychiatric problems. Gender variant behavior and even the desire to be of another gender can be either a phase or a variation of normal development without any adverse consequences for a child's current functioning. Prospective studies show that gender variance in clinical populations is associated with later homosexuality or bisexuality as well as gender dysphoria in adulthood. Nonetheless even in clinical populations the vast majority cases of gender dysphoria do not persist from childhood into adulthood. When presenting during adolescence it seems much less likely that gender dysphoria will desist. Gender dysphoria can lead to such high-risk behaviors during adolescence as soliciting illicit hormones or silicone injections, drug and alcohol abuse, or suicide. Peer rejection can be a major issue for the child or adolescent with gender nonconformity leading to poorer social relationships in general. In childhood this is more of a problem for feminine boys than for masculine girls (tomboys). There seems to be a contemporary need for society to acquiesce to the desires of children with GD (or to normalize children with ambiguous genitalia). This may be motivated by the apparent fundamental human need to appear normal, perhaps to fill the social need of belonging to a group. Ironically, the desire to “fit in” survives despite telling our children to “be themselves” when the need to be accepted into the group is the issue and being like others is the goal. After adolescence this belonging to the majority group seems less important. There is no single clinical course for children with gender dysphoria although most children do not persist in their gender dysphoria. There is some evidence to suggest that those with more extreme measures of cross gender behavior and gender dysphoria are more likely to persist. Perhaps two-thirds of children with GD develop a homosexual orientation in adolescence. Anxiety may be related to real or perceived rejection, hostility, and abuse because of the teen’s transgender status or fear of being discovered. Transgendered teens have committed suicide, perhaps 50% have serious suicidal thoughts, and one third have actually made a suicide attempt. Gender non-conforming adolescents seem to have better psychological health than transgender adults. It could be that the stress associated with the desire to be of the other gender leads to socioemotional problems including depression and anxiety. Also there may be social ostracism and rejection by same-sex peers. Concurrent conditions such as ADHD, bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders, and autistic spectrum disorders may make a child more vulnerable to social ostracism or gender confusion. This helps explain some disturbing reactions such as emotional hypersensitivity, severe mood swings, oppositional behavior, temper tantrums, attention problems, anxiety, and depression. TREATMENT OPTIONS Children, adolescents, and adults manifesting such gender variation are referred to mental health professionals for assessment and treatment. However, few providers have much experience with these rare disorders. Other identified barriers to caring for gender nonconforming and transgender youth include variability in clinical approach by community providers, a general lack of comfort in and knowledge of gender identity issues, and multiple clinician (and from various disciplines) involvement with poor coordination and disagreement as to what constitutes competent and comprehensive care. The latter relates to the lack of solid evidence to inform practice. Prior to treatment of gender dysphoria directly, there must be exclusion of psychiatric conditions that are similar to or contribute to gender dysphoria. As the most basic initial step a comprehensive psychiatric evaluation is necessary to carefully assess and treat any underlying comorbidities that may be impacting gender identity and dysphoria. The gender dysphoria may have been caused by cooccurring psychopathology, family and social rejection, psychological distress due to the real discrepancy between psychological and anatomic gender, or by family psychopathology. Although psychopathology may be the result rather than the underlying problem of GD, sexual reassignment may also be sought as a solution to non-gender problems. Even for experienced clinical teams, it is more complicated to make an accurate diagnosis of gender dysphoria in adolescents who are not functioning well. It is a challenge to disentangle the gender and autistic spectrum disorders. There should be assessment of any comorbid psychiatric diagnoses as well as environmental influences on a child's gender development including school, peers, extended family members, siblings, popular culture, and patterns of the individual's coping strategies and resilience capacities. An ongoing treatment relationship will expand the opportunities to understand the dynamic interactions between psychiatric comorbidities and various external influences on the individual. There are three general approaches to management and treatment of gender dysphoria: 1) No active intervention 2) Attempt to lessen gender dysphoria by helping the child accept his biological sex and the associated gender identity 3) Encourage a transition to the cross-gender role. No systematic data are available on the effectiveness of these different treatment approaches. As one would expect, without strong evidence to guide clinical interventions, there are diverse and controversial opinions. The first approach offers no active intervention to lessen gender dysphoria or cross gender behavior. This hands-off approach is based on the assumption that 80 to 90% of children even without treatment will have resolution of gender dysphoria upon reaching adolescence. The downside to this strategy is that the 1020% who persist upon reaching adolescence are more firmly established in their diagnosis and less responsive to interventions. Especially early in development one should avoid definitive labels on a person’s cross-gender identity because it is yet evolving. It would probably not best serve the child to refer to him or her by an alternate gender name or pronoun. Many transgender children do not express or experience distress or dysfunction with their assigned gender, despite some having the desire to be the other sex. And the overwhelming majority of gender nonconforming children desist from their cross gender identifications and behaviors by adolescence. The outcome may relate to severity of symptoms. However, if present after puberty gender dysphoria rarely resolves. Another approach attempts to lessen gender dysphoria by helping the child accept his biological sex and the associated gender identity. It just makes sense that the individual is best served by accepting one’s biology instead of rejecting it. The child is assisted with expanding sex-role stereotypes and flexibility in both directions. Dysphoria may be reduced by broadening the more narrow societal definitions of gender to allow for the patient's specific variation in gender role attitudes, preferences, and behaviors. This helps the person accept his biological sex through expanding the sex-role stereotypes to accommodate his preferences. The clinician should offer education and resources toward that end. For example, it can be instructive to demonstrate changes in societal gender norms over the course of human history in regard to care, clothing, and jewelry. Most children express relief when they can have a way of defining and understanding themselves as just a different kind of boy or girl. Educating parents and communities about expanding gender role and accepting cross-gender behaviors may complement this individual treatment goal. The matter of gender identity is patiently explored in psychotherapy. Selfacceptance and expanding gender role behavior are encouraged. The therapist attempts to increase the child's comfort by expressing behaviors and identifications consistent with his or her natal sex. The clinician best not rush to collude with young patients in the idea that unease and uncertainty are all related to an unclear vision of the most correct gender. Identity diffusion is a normal part of adolescent development. While it may be that a broader conception of gender would be advantageous to some, and that any one individual may over the course of a life come to see him or herself as more masculine or feminine, making a narrow determination of an incorrect gender in adolescence is shortsighted. The benefits of assuming a cross gender social role in the school setting is controversial. It is not realistic to expect that everyone will accommodate cross sex dress and behavior and it may be best to help the transgendered child fit better into his environment. It is adaptive to figure out how to negotiate between expressing one's real self and acclimating to the real world so we submerge aspects of ourselves depending on the context. So it is helpful to create safe spaces for the child to play, explore same-gender activities, and reinforce congruent gender role behaviors. This is sometimes accomplished through activities in art, theater, music, and creative play. Paying special attention (even negative attention) to either gender role behaviors may serve to reinforce them. It is generally a good practice to provide positive attention independent of any gender-specific behavior. Strategies to reduce peer rejection and ostracism can improve the social isolation and alienation that contribute to emotional distress. Reducing dependence and enmeshment with the caregivers addresses the typical imbalance between attachment and exploration. Families are discouraged from overtly or inadvertent reinforcing cross-gender behaviors. Minimizing family punishment, ridicule, and criticism helps reduce the risk for depression, suicide and substance abuse. Families are encouraged to have more tolerance of gender discordance while setting limits on expression of gender discordant behavior to the extent that these limits are necessary to decrease risk for peer or community harassment. Increased levels of harassment and victimization by peers are related to increased levels of depression and anxiety and decreased levels of self-esteem. The focus of these interventions is more on reducing the dysphoria than the gender role behaviors. However, hastening the desistence (i.e. fading) of gender discordance, is still an overarching treatment goal. Adolescents may resist therapy because of perceptions that they are psychosocially well-adjusted except for their gender issues. General psychotherapeutic interventions that improve the individual’s adaptive ego strength and resilience, expand the repertoire of coping skills, and enhances understanding are potentially helpful. The frequency of treatment is guided by the severity of associated psychopathology and the degree of functioning. Collaborative treatment with other provider’s patients and families often view the mental health component of treatment as a means to achieving the medical interventions. Once achieving the primary goal, mental health follow-up is poor. Acute safety issues are dressed through psychiatric hospitalization. Play (psychomotor) therapy may help youth who do not easily verbalize feelings. Treatment roadmaps and narrative medicine (writing and telling a story with drawings and pictures) may assist with the impatient adolescent. Ongoing support of the youth and parents through the therapeutic treatment relationship is highly desirable. There are few experienced clinicians and little prospective evidence to guide treatment. Most parents initially question the diagnosis and whether the child is going through a phase or has been influenced by peers or social media or is otherwise exploring sexuality. There is also the concern that improvements in psychopathology following diagnosis and early treatment are transient and will return when experiencing ongoing discrimination, rejection, or disappointments. A more cautious clinical approach as opposed to strongly advocating for the presence and maintenance of the disorder is appreciated by most parents. Family therapy may be necessary to help resolve conflicts between family members. Parents may need guidance on how to relate to their child in a way that does not contribute to more gender dysphoria. Healthy boundaries and limits must still be provided by parents and will be tested by the gender variant adolescent. Parents often struggle with the conflict between validating the child's current stated wishes versus succumbing to the stigma that environmental influences may impose. Dealing with recommendations of other providers such as pediatricians, school psychologists, teachers, therapists involved in the child's treatment may reflect inadvertent or blatant opposing ideas and biases. With adolescents who are gender nonconforming, standards for establishing patient eligibility and readiness for treatment may be inconsistent across providers. Improving adaptation to the multiple external and internal challenges is necessary psychosocial treatment. Support groups may be helpful but online and other resources cannot be relied upon to give the best advice for any specific individual. Additionally this area has been highly politicized. A listserv through the CNMC helps families to know that they are not alone. The social challenges for both the child and the parents are the hardest because our culture expects and is designed to support extremely binary gender roles. Parents are encouraged to be straightforward and share the fact that my child is nonconforming in gender role behavior and has been that way since an early age. The message is conveyed in a way that communicates love and support for their child. They should be discouraged from openly sharing the associated emotional difficulties along the way. Instead of converting others it is best to be surrounded by people who are not rejecting. Families often deal with grief and loss around losing a son or daughter and the normative hopes and dreams and expectation for their child's future. They grieve the loss of anticipated stability as their child grows older and progresses through normal development. They worry about reducing the reproductive possibilities. They are concerned about their child's succeeding at school, work, interpersonal relationships, and family formation. They worry about the physical and emotional safety of their child. They may respond with reduced expectations of the child's achievements and expectations around the household and fail to set appropriate structure and limits that all adolescents need. They may withdraw and fail to give the adolescent needed support. Most parents have encouraged their child to limit cross dressing and other cross gender behaviors that may be focus of negative attention in public and rather practice them in the privacy of their own home. Some parents believe that group participation may prematurely validate and actually promote a course of action that the child would not otherwise take. However listening to the stories of others and talking about personal struggles contribute to developing insight, adaptive strategies, and collective problem-solving. For those with persistence of gender dysphoria into adulthood, a third approach encourages a transition to the cross-gender role. Gender discordance presenting in adolescents or adults is more likely to persist than when presenting in childhood, so treatment approaches often assume persistence of gender discordance. As adults, those with gender dysphoria try to live as if they belong to the opposite sex. Many successfully hide their sex from coworkers and friends. Sexual intimacy is restricted; a majority of transsexuals don’t marry, and when they do, the marriages usually fail. Because they experience themselves as members of the opposite sex, they prefer normal heterosexual partners of the same biological sex, but they do not view themselves as “homosexual” because of their cross-gender identity. At this point the goal of psychotherapy becomes the alleviation of emotional problems arising from the transsexualism. Sex reassignment (also referred to as normalizing or gender-conforming procedures) is controversial and includes real-life experience as the other gender with prescribed hormones, and surgery to change the genitals and other sex characteristics. Gender atypical behavior by itself should not be taken as an indicator for sex reassignment. A comprehensive psychological evaluation and an opportunity to explore feelings about gender with a qualified clinician are required over a period of time. It is important to remember that transient periods of uncertainty about one's gender are common but should not be interpreted as a clear indication for sex reassignment. Once the adult with cross-gender identity clearly decides to switch sexes, some professionals support the patient in seeking hormonal and surgical sex reassignment. Other clinicians have ethical qualms about supporting the individual’s desire for surgical sex reassignment and remove themselves from the case and refer the person to another clinician. Much of the distress that transgender adolescents experience in puberty is related to the emergence of secondary sex characteristics. Sex hormone suppression through the use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues can be used to reversibly delay development of secondary sex characteristics to minimize the later need for surgery and until maturity allows for informed consent. Most importantly puberty suppression will inhibit the spontaneous formation of a gender identity corresponding to natal sex. Another drawback would be insufficient penile and scrotal tissue to construct labia and a vaginal vault in the future. Suppressing puberty does not give the adolescent the choice of freezing sperm prior to fertility. Of course delaying treatment until adulthood may have its own psychological drawbacks including the development of depression, suicidality, anxiety, and oppositional defiant disorders accompanied by school dropout and social withdrawal. So the rationale for early treatment is that transgendered youth may be spared the burden of having to live with irreversible signs of what they perceive to be the wrong secondary sex characteristics and more surgical procedures. This is often considered when GD intensifies instead of decreases during early puberty and there are no serious psychosocial problems interfering with diagnosis or treatment. Medical treatment to suppress puberty is expensive and not routinely covered by insurance and provides logistical hurdles that may not be affordable by the family. This may contribute to the adolescent’s perception that his or her parents are unsupportive or rejecting. Protective laws may preclude such treatment in certain states or countries and of course parents must be involved in treatment decisions prior to the age of legal consent. Most gender dysphoric youths choose to live in the desired gender roles simultaneously with the beginning of puberty suppression. Hormone therapy is the next step in sex reassignment and is considered at around the age of 16 years when there is sufficient maturity for independent medical decision-making. It is an absolute requirement that the social gender role change will occur simultaneously. It is desirable that gender dysphoric patients undergo a prolonged period of living in the desired gender in most or all domains of everyday life as appropriate for the patient's age before undergoing any poorly reversible or irreversible medical treatment such as cross gender hormone treatment or gender confirming genital surgery. Hormone therapy is easier and safer when following suppressed puberty. The resulting physical changes and impact on fertility are only partially reversible. Most adolescents who have received hormonal therapy report persistent cross gender identity and improved psychological functioning. A majority of adults with cross-gender identity express the strong desire to change their sexual anatomy permanently. In the United States, two to eight times more men than women seek surgical sex reassignment. To qualify for a surgical sex transformation, surgeons typically require that patients live as the opposite sex for at least 2 years, during which time they should demonstrate minimally adequate social and occupational functioning, be able to sustain enduring friendships, and be free of major psychopathology. Some surgeons in private practice perform sex reassignment surgery without any psychiatric evaluation but this would be unusual. Some individuals with gender dysphoria seek surgery in foreign countries at a lower cost, where psychiatric evaluations are rare. Surgical procedures are accompanied by prescriptions for estrogen or testosterone to induce the secondary sex characteristics of the other sex. Education about the short-term and long-term costs and benefits of sex reassignment will help the individual have a balanced view. Achieving congruence of gender identity and anatomical sex through reassignment surgery is an expensive and extreme intervention that potentially inflicts harm and dysfunction. Realistic expectations of the neo-vagina, neo-phallus, and sexual functioning (e.g. loss of orgasm and the ability to reproduce) are necessary. There is the real possibility of aggressive reactions when engaged in sexual encounters where the partner is not aware of the person’s natal sex. The surgical procedure and hormone therapy may not achieve the acceptance or validation of gender identity that the person may be seeking. Identity is not really about appearance so changing physical attributes does not change the identity, the genetic material, or the essence of the individual. This sex reassignment approach is inconsistent with the treatment of similar psychopathology such as Body Dysmorphic Disorder or Body Integrity Identity Disorder where noninvasive strategies are exclusively employed to reduce the patient’s suffering (see below). Patients and their families perceive that they have almost no choice if they are choosing between a guaranteed low quality of life and the possibility of a more fulfilling life through sex reassignment. Based on the existing evidence, the clinician is ethically bound to avoid giving, even inadvertently, such an impression. Clinician neutrality regarding outcomes is often recommended in order to allow the youth to openly explore gender dysphoric feelings and treatment wishes. This recommendation sounds good on the surface but with the current evidence may not be on solid ethical ground. With all these problems, it seems that all other treatment options should be exhausted before a surgical solution is entertained to relieve psychological distress. With a few exceptions, those who have had sex reassignment surgery do not express regrets, no longer report dysphoria, and claim to be functioning well socially and psychologically. However, those patients selected for this treatment were the best-functioning from the start and may have done equally well with alternative treatment. There is little evidence to demonstrate actual improvement in overall functioning. In fact, psychological, relational, and vocational adjustment of individuals with gender dysphoria who obtain sex reassignment surgery are not significantly different from those who do not. In terms of a cost–benefit analysis, surgical sex reassignment is difficult to justify. However, for the gender satisfaction they anticipate, many adults with gender dysphoria continue to work for years to save up money to pay for this surgery since it is not typically covered by health insurance. ETHICAL ISSUES Perhaps the major ethical dilemma for gender reassignment surgery is the potential for doing harm where evidence is lacking. The more popular treatment options may lead to permanent irreversible harm and are inconsistent with approaches to similar clinical conditions. For example, the treatment of non-gender related body dysmorphic disorder seeks to minimize surgical interventions and promote self-acceptance. There are those who express concern that sex reassignment is a form of sanctioned self-mutilation supported by the politics surrounding sexual identity and orientation and by a dichotomous societal preference regarding gender. They argue that a different approach would prevail for other similar but non-politicized clinical situations. For example, Body Integrity Identity Disorder (BIID) denotes a syndrome in which a person is preoccupied with the desire to amputate a healthy limb. The desire to amputate seems related to a disturbance in the person's perception that the limb is not a genuine part of himself. Limb amputation can relieve temporarily the patient's feeling of distress without necessarily adjusting the patient's own identity misperception. Persons with this disorder seek surgical correction but the medical community is generally united in pursuing noninvasive treatment strategies to reduce the patient’s suffering. The patient retains the most function and is thus best served by incorporating the limb as part of a fully integrated and unified whole identity. As with gender dysphoria the persons receiving the surgery express no regrets afterward, but have clearly lost some degree of functioning. They may also initially report less distress although the ambulation difficulties will undoubtedly provide new challenges with social and emotional consequences. Because of the reduction in functioning, this lack of regret seems insufficient for physicians to support the process of relieving psychological distress through surgery. Gender reassignment can be clearly distinguished from surgeries that are cosmetic, restorative, or reconstructive. References and Resources Guevote – The Way I Feel is How I Am (1996) is a documentary film portraying the daily lives of a significant percentage of girls born in a Caribbean village who change into men at puberty because of a genetic variation that conveys androgen insensitivity. The Gender and Sexuality Development Program at Children’s National Medical Center (CNMC) in Washington, DC (www.childrensnational.org/gendervariance) provides psychosexual evaluations and therapeutic services on an outpatient basis. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) is an international and multidisciplinary professional organization devoted to the understanding and treatment of gender identity disorders by promoting evidence based care, education, research, advocacy, public policy and respect in transgender health. www.wpath.org American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. Barlow, D.H., Reynolds, E.J., & Agras, W.S. (1973). Gender identity change in a transsexual. Archives of General Psychiatry, 28, 569–576. Kilgus, M.D. (2014) Dysphoria about gender. In M.D. Kilgus and W.S. Rea (Eds.), Essential Psychopathology Casebook (pp. 367-399), New York: Norton. Rekers, G.A., Kilgus, M.D., & Rosen, A.C. (1990). Long-term effects of treatment for childhood gender disturbance. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality, 3(2), 121–153. Rekers, G.A. (1995). Handbook of child and adolescent sexual problems (pp. 255–271). New York: Lexington Books. World Health Organization. (2007). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (10th ed.). Available at http://www.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icd10online/.