* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Magnetic Force on an electric current

Neutron magnetic moment wikipedia , lookup

Magnetic field wikipedia , lookup

Magnetic monopole wikipedia , lookup

History of electromagnetic theory wikipedia , lookup

Aharonov–Bohm effect wikipedia , lookup

Electromagnetism wikipedia , lookup

Electrical resistance and conductance wikipedia , lookup

Lorentz force wikipedia , lookup

Superconductivity wikipedia , lookup

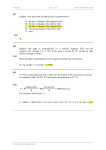

Magnetic Force on an electric current: A magnetic force acts on a current in a magnetic field due to the interaction of the surrounding field and the field caused by the current (electromagnetic induction). F= nBIl(sin) F: magnetic force on an electric current, n: number of current-carrying wires, B: magnetic field (strength) caused by magnets around the wires, I: current travelling through the wires, l: length of the wires, : angle between the current and the magnetic field, N.B. sin(90o)= 1, sin(0o)= 0, .: F┴ = nBIl, F║= 0, .: B = [T = Nm-1A-1] i.e., Magnetic field (strength) is the force exerted by a magnet on a current-carrying wire per meter of current-carrying wire. Right-Hand Grip Rule: Imagine that you grab the wire with your right hand so that your thumb points in the direction of the current (I), your fingers will then point in the direction of the magnetic field lines (B) induced by the current. ‘I’ is the conventional current, i.e., opposite to electron flow! ‘B’ is the magnetic field from N to S created by the current. Right-Hand Slap Rule: With your flat, open right hand, when your fingers point in the direction of the magnetic field (B), and your thumb points in the direction of the current (I), then the magnetic force (F)on the current is in the direction of you palm: ‘slap’. ‘I’ is the conventional current, i.e., opposite to electron flow! ‘B’ is the magnetic field from N to S that is affecting the current. ‘F’ is the magnetic force on the current caused by the interaction of the magnetic field affecting the current and the magnetic field created by the current. Magnetic Flux: The amount of magnetic field passing through an area is called the magnetic flux, , measured in Webers, ‘Wb’: = BAsin, B = magnetic field (strength) = [T = Teslas] A = area being considered = [m2] = angle between the field and the area, sin(90o)= 1, sin(0o)= 0, .: ┴ = BA = max, ║= 0 = min, = [W] = [Tm2], [T] = [Nm-1A-1] .: = [NmA-1] = [JA-1] Because electromagnetic induction is caused by a relative change: = E/I, E = energy transformed into electrical energy, I = current carrying that electrical energy, i.e., Magnetic Flux is the energy transformed per current induced. lsin), .: F┴ = nBIl = Fmax, F║= 0 = Fmin, Faraday’s Law: The average magnitude of emf, av, induced in a loop of wire is equal to the rate of change of the magnetic flux, /t, passing through that loop: av = n/t, av = the average emf (voltage) induced in the ends of the loop of wire. = the change in flux (= f inal – initial) due to any of; B, A, or . t = the time interval in which the change in flux took place. n = number of loops in the coil, Lenz’s Law: The amount of emf, , induced in a coil is equal to the rate of change of the amount of magnetic flux, /t, passing through a number of loops, n, so that the magnetic field, B, that is produced by the current, I, caused by the emf, , is in a direction that opposes, ‘–’, the change in flux: = –n /t, Alternating Current: When an electrical current reverses direction (i.e., alternates) regularly and rapidly it is called an ‘alternating current’, AC. Generally, alternating currents are sinusoidal (i.e., a graph of its current over time is shaped like a sine wave). It can be described by wave-like properties: I= A∙sin(2∙∙f∙t) I = conventional current (amperes), f = frequency (hertz) = number of cycles per second (Hz). T: period = time required for one cycle (s) = 1/f. t = time (seconds) A = amplitude (amperes) = magnitude from zero to maximum (peak). RMS and Peak Values: The Root Mean Square (RMS) value of an alternating current value is its average magnitude. This means that the equivalent amount of power is transformed/transferred when a circuit is connected to a DC source or an AC source with the same RMS Voltage as the DC Voltage. Vrms = Vpeak/√2, AND Irms = Ipeak/√2, p-p: peak-to-peak = magnitude from maximum to minimum. rms: root mean square of values: xrms =√( (xav–x)2), P(Vrms) = P(VDC): Vrms = VDC ( for equivalent DC power). P(Irms) = P(IDC): Irms = IDC (for equivalent DC power). Electric Power: Electrical power is transmitted when a voltage, ‘V’, across a component results in a current, ‘I’, through that component. This is because the voltage is a measure of the electrical energy, ‘E’, transferred or transformed by each unit of charge, ‘q’, and the current is a measure of the rate of transfer of unit charges: ‘q/t’. P= IV = q/t * U/q = U/t P = power transformed by device I = conventional current through the device (amperes) V = voltage drop across the device q = charge transmitted across device t = time taken to transmit charge or transform energy, U = electrical potential energy associated with each transmitted charge, Electrical Dissipation (Transmission Losses): In ohmic devices, such as conductors, the current through a component depends on the voltage across it and the resistance, ‘R’, of that component. Resistance, measured in ohms, , is a measure of the tendency of a component to dissipate the energy that is transmitted through it. Dissipation is the transformation of energy of one kind (e.g., electrical energy) into heat energy. This relation, V=IR, is known as ‘Ohm’s Law’. V= IR Power Loss: The rate at which energy is transformed from electrical to heat energy in a conductor (and therefore lost from the electrical circuit) depends on the product of the square of the current through the conductor and the resistance of the conductor: P= IV, V= IR .: P= I·IR = I2R; Ploss= I2R That is, the power lost from a conductor is proportional to both the current through it and the resistance of it: the higher the current or resistance the more power is lost. Operation of a Transformer: A transformer is made up of two coils of wire wrapped around opposite sides of a hollow square/ring of iron. When one of the coils (the primary coil) is connected to an alternating current (AC) source it will produce a changing magnetic field inside the iron core, according to the Faraday-Lenz Law: = –n /t. This will then produce a changing magnetic field inside the other coil (the secondary coil) which will induce a voltage/current in that coil: again according to the Faraday-Lenz Law: = –n /t. If the area of the two coils is equal (as usual), then the rate of flux, /t = –p /np, produced by the primary coil will be the equal to the rate of flux, /t = –s /ns, produced in the secondary coil. np /ns = Vp /Vs = Is/Ip The ratio of primary-to-secondary coils is proportional to the ratio of the voltages and inversely to the ratio of the currents. Transformers with np > ns, are step-down, np < ns, are step-up.