* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Operant Conditioning (BF Skinner)

Psychophysics wikipedia , lookup

Educational psychology wikipedia , lookup

Behavior analysis of child development wikipedia , lookup

Behaviour therapy wikipedia , lookup

Learning theory (education) wikipedia , lookup

Classical conditioning wikipedia , lookup

Verbal Behavior wikipedia , lookup

Psychological behaviorism wikipedia , lookup

Behaviourism

Behavioural (or "behavioral") theory in psychology is a very substantial field: follow the

links to the left or right for introductions to some of its more detailed contributions

impinging on how people learn in the real world. How I have the effrontery to produce a

single page on it amazes even me, whatever my reservations about it!

Behaviourism is primarily associated with Pavlov (classical conditioning) in Russia and

with Thorndike, Watson and particularly Skinner in the United States (operant

conditioning).

Behaviourism is dominated by the constraints of its (naïve) attempts to

emulate the physical sciences, which entails a refusal to speculate about

what happens inside the organism. Anything which relaxes this

requirement slips into the cognitive realm.

Much behaviourist experimentation is undertaken with animals and

generalised.

In educational settings, behaviourism implies the dominance of the

teacher, as in behaviour modification programmes. It can, however, be

applied to an understanding of unintended learning.

For our purposes, behaviourism is relevant mainly to:

Skill development, and

The "substrate" (or "conditions", as Gagné puts it) of learning

Classical conditioning:

is the process of reflex learning—investigated by Pavlov—through which an

unconditioned stimulus (e.g. food) which produces an unconditioned response

(salivation) is presented together with a conditioned stimulus (a bell), such that the

salivation is eventually produced on the presentation of the conditioned stimulus alone,

thus becoming a conditioned response.

This is a disciplined account of our common-sense experience of learning by association

(or "contiguity", in the jargon), although that is often much more complex than a reflex

process, and is much exploited in advertising. Note that it does not depend on us doing

anything.

Such associations can be chained and generalised (for better of for worse): thus "smell

of baking" associates with "kitchen at home in childhood" associates with "love and

care". (Smell creates potent conditioning because of the way it is perceived by the

brain.) But "sitting at a desk" associates with "classroom at school" and hence perhaps

with "humiliation and failure"...

This site goes further into Watson's ideas, beyond Pavlov, and the "Little Albert" experiment.

Operant Conditioning

If, when an organism emits a behaviour (does something), the consequences of that

behaviour are reinforcing, it is more likely to emit (do) it again. What counts as

reinforcement, of course, is based on the evidence of the repeated behaviour, which

makes the whole argument rather circular.

Learning is really about the increased probability of a behaviour based on reinforcement

which has taken place in the past, so that the antecedents of the new behaviour

include the consequences of previous behaviour.

Summary of Skinner's ideas On operant conditioning Skinner's own account Wikipedia on operant

conditioning And here with diagrams of experimental set-ups and video

The schedule of reinforcement of behaviour is central to the management of effective

learning on this basis, and working it out is a very skilled procedure: simply reinforcing

every instance of desired behaviour is just bribery, not the promotion of learning.

Withdrawal of reinforcement eventually leads to the extinction of the behaviour, except

in some special cases such as anticipatory-avoidance learning.

Notes

Two points are often misunderstood in relation to behaviourism and human learning:

The scale: Although later modifications of behaviourism are known as S-OR theories (Stimulus-Organism-Response), recognising that the organism's (in this

case, person's) abilities and motivations need to be taken into account, undiluted

behaviourism is concerned with conditioning and mainly with reflex behaviour.

This operates on a very short time-scale — from second to second, or at most

minute to minute — on very specific micro-behaviour. To say that a course is

behaviourally-based because there is the reward of a qualification at the end is

stretching the idea too far.

Its descriptive intention: Perhaps because behaviourists describe experiments in

which they structure learning for their subjects, attention tends to fall on ideas such

as behaviour modification and the technology of behaviourism. However,

behaviourism itself is more about a description of how [some forms of] learning

occur in the wild, as it were, than about how to make it happen, and it is when it is

approached from this perspective that it gets most interesting. It accounts

elegantly, for example, for ways in which attempts to discipline unruly students

actually make the situation worse rather than better.

(This point is heretical!) For human beings, reinforcement has two components,

because the information may be cognitively processed: in many cases the "reward"

element is less significant than the "feedback" information carried by the

reinforcement.

Applied to the theory of teaching, behaviourism's main manifestation is "instructional

technology" and its associated approaches: click below for useful guides.

For practical illustration of reinforcement as feedback, look here. Instructional Design & Learning Theory

(Mergel 1998) Gagné's model as an example of instructional technology

Online accessed 2-12-10 at http://www.learningandteaching.info/learning/behaviour.htm

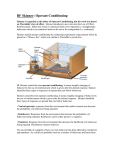

Operant Conditioning (B.F. Skinner)

Overview:

The theory of B.F. Skinner is based upon the idea that learning is a function of change in

overt behavior. Changes in behavior are the result of an individual's response to events

(stimuli) that occur in the environment. A response produces a consequence such as defining

a word, hitting a ball, or solving a math problem. When a particular Stimulus-Response (S-R)

pattern is reinforced (rewarded), the individual is conditioned to respond. The distinctive

characteristic of operant conditioning relative to previous forms of behaviorism (e.g.,

Thorndike, Hull) is that the organism can emit responses instead of only eliciting response

due to an external stimulus.

Reinforcement is the key element in Skinner's S-R theory. A reinforcer is anything that

strengthens the desired response. It could be verbal praise, a good grade or a feeling of

increased accomplishment or satisfaction. The theory also covers negative reinforcers -- any

stimulus that results in the increased frequency of a response when it is withdrawn (different

from adversive stimuli -- punishment -- which result in reduced responses). A great deal of

attention was given to schedules of reinforcement (e.g. interval versus ratio) and their effects

on establishing and maintaining behavior.

One of the distinctive aspects of Skinner's theory is that it attempted to provide behavioral

explanations for a broad range of cognitive phenomena. For example, Skinner explained

drive (motivation) in terms of deprivation and reinforcement schedules. Skinner (1957) tried

to account for verbal learning and language within the operant conditioning paradigm,

although this effort was strongly rejected by linguists and psycholinguists. Skinner (1971)

deals with the issue of free will and social control.

Scope/Application:

Operant conditioning has been widely applied in clinical settings (i.e., behavior modification)

as well as teaching (i.e., classroom management) and instructional development (e.g.,

programmed instruction). Parenthetically, it should be noted that Skinner rejected the idea of

theories of learning (see Skinner, 1950).

Example:

By way of example, consider the implications of reinforcement theory as applied to the

development of programmed instruction (Markle, 1969; Skinner, 1968)

1. Practice should take the form of question (stimulus) - answer (response) frames which

expose the student to the subject in gradual steps

2. Require that the learner make a response for every frame and receive immediate feedback

3. Try to arrange the difficulty of the questions so the response is always correct and hence a

positive reinforcement

4. Ensure that good performance in the lesson is paired with secondary reinforcers such as

verbal praise, prizes and good grades.

Principles:

1. Behavior that is positively reinforced will reoccur; intermittent reinforcement is

particularly effective

2. Information should be presented in small amounts so that responses can be reinforced

("shaping")

3. Reinforcements will generalize across similar stimuli ("stimulus generalization")

producing secondary conditioning

References:

Markle, S. (1969). Good Frames and Bad (2nd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Skinner, B.F. (1950). Are theories of learning necessary? Psychological Review, 57(4), 193216.

Skinner, B.F. (1953). Science and Human Behavior. New York: Macmillan.

Skinner, B.F. (1954). The science of learning and the art of teaching. Harvard Educational

Review, 24(2), 86-97.

Skinner, B.F. (1957). Verbal Learning. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Skinner, B.F. (1968). The Technology of Teaching. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

Skinner, B.F. (1971). Beyond Freedom and Dignity. New York: Knopf.

Online accessed 2-12-10 at http://tip.psychology.org/skinner.html