* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Atomism, epigenesis, preformation and preexistence: a clarification

Sociocultural evolution wikipedia , lookup

Unilineal evolution wikipedia , lookup

Creation and evolution in public education wikipedia , lookup

Evolutionary developmental biology wikipedia , lookup

Punctuated equilibrium wikipedia , lookup

Hindu views on evolution wikipedia , lookup

Catholic Church and evolution wikipedia , lookup

Hologenome theory of evolution wikipedia , lookup

Koinophilia wikipedia , lookup

Genetics and the Origin of Species wikipedia , lookup

The eclipse of Darwinism wikipedia , lookup

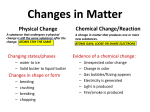

Biological Journal of Ihe Linnean Socie!y ( 1986), 28: 33 1-341 Atomism, epigenesis, preformation and pre-existence: a clarification of terms and consequences OLIVIER RIEPPEL F.L.S. Palaontologisches Institut und Museum der Universitat, Kiinstlergasse 16, CH-8006 Zurich, Switzerland Received 16 Juh 1985, accepted for publication 4 February 1986 The meaning of the terms atomism, epigenesis, preformation and pre-existence is clarified by a historical analysis. Today, two alternative models of organismic change are opposed to each other. Atomism views the organism as being composed of traits or atoms: it implies the possibility of gradualistic change and a nominalistic species concept, while an increase in complexity is identified as an addition of new parts. Epigenesis, in contrast, implies the possibility of saltational change and an essentialistic species concept, while an increase in complexity is considered to result from an enhanced compartmentalization and differentiation of the originally homogeneous primordium. Schwabe & Warr’s (1984) ‘genetic potential hypothesis’ qualifies as pre-existence at the genotypic level. KEY WORDS:-Ontogeny - phylogeny - preformation - epigenesis. CONTENTS Introduction . . . . . . . . . Aristotle’s critique of atomism . . . . . William Harvey and his notion of epigenesis . Pre-existence and the correlation of parts . . Atomism and epigenesis in the eighteenth century Darwinism and atomism . . . . . . The modern critique of Darwinism . . . . Modern preformationism . . . . . . Atomism versus epigenesis . . . . . . References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33 1 332 333 334 335 337 338 338 339 340 INTRODUCTION All scientific endeavour must be guided by theoretical premises and methodological rules.. The results of some investigations are determined by empirical data but even more so by the way these data are interpreted, the interpretation following theoretical premises inherent in the vocabulary used to communicate about research programmes. A critical evaluation of the meaning of certain notions, their theoretical content and consequences is therefore important in all fields of natural science. 0024-4066/86/08033I I + I 1 $03.00/0 33 1 0 1986 The Linnean Society of London 332 0. RIEPPEL The present paper deals with critical terms derived from the vocabulary of modern embryology. The study of mechanisms of ontogenesis plays a n increasingly important role in the study of tempo and mode of evolution (e.g. Bonner, 1982; Raff & Kaufman, 1983; Arthur, 1984). I n this context, notions like preformation or epigenesis make their frequent reappearance (e.g. Katz & Goffman, 1981; Schwabe & Warr, 1984), and the relative merits of these two concepts are discussed in the light of modern understanding of embryogenesis (e.g. Mayr, 1982); however, at the same time the theoretical content of these notions is by no means clear. The reasons for this are twofold. I n the field of the history of science a controversy has been triggered by Jacques Roger (1971; first edition 1963), who distinguished between preformation and pre-existence (see Wilkie, 1967; Bowler, 1971; Hofieimer, 1982), while such notions were not unequivocally defined in the great debate which dominated biology during the eighteenth century. The purpose of this paper is to clarify the meaning of these models of ontogeny in their historical context, and to investigate the theoretical implications they carry into present-day discussions. ARISTOTLE’S CRITIQUE OF ATOMISM The atomistic philosophy of Democritus, revised by Epicurus and popularized by Lucretius, considered the organism to be composed of parts or atoms. Each part of the adult body of both sexes was thought to be represented by equivalent, i.e. preformed, but miniaturized, atoms in the male and female seminal fluids. Generation would consist of a mixture of the two seminal fluids within the mother’s womb stirred by the warmth of the maternal body, and it would result in the aggregation of the atoms to form the fetus. T h e system appeared to explain the similarity of the offspring with both parents, while ‘errors’ in the combination of atoms would result in malformations. The embryo, according to atomists, was a formation de novo, resulting from the combination of preformed parts derived from the parental bodies (RegnC11, 1967; Kullmann, 1979; see also Lucretius Carus, D e rerum natura, liber I. 169-170). This is the original theory of preformation which Aristotle set about to criticize. How do the parts forming a larva derive from the sexually mature imago? Why does the newborn boy lack a beard? Why are mutilations not heritable? Why does usually only one child result from the combination of two seminal fluids?-These were some of the questions he asked (Kullman, 1979). Based on the observation of the development of the chick (Kullman, 1979: 43), Aristotle devised his own theory of generation which was later-through the work of W. Harvey (1651)-to become known as epigenesis. The hallmark of this theory is that the parts of the embryo, forming de novo, are not all present and preformed at the beginning of its development, but arise one after the other. The male semen is derived from the blood which itself is prepared by the heart. It is endowed with the soul which represents the principle of form and of movement. The ‘knowledge of form’ and the potential movement are transmitted via the aura seminalis to the receptive female substance (the menstrual blood) within which the form of the species becomes actualized by the effect of the actual movement of the heart, the first part of the embryo to be formed (Balss, 1943: 213). The species-specific form is eternal and hence ATOMISM AND EPIGENESIS 333 immutable; its continuous actualization by generation provides a means of the partaking of ephemeral individuals in divine eternity (Balss, 1943: 183). In contrast to Plato, Aristotle held the causu formalis to be immanent in matter itself, and so is the telos of the developmental process, the actualization of this form (Kullman, 1979: 19). Nevertheless, the critique of nominalism hit Aristotelianism just as severely as Platonism. WILLIAM HARVEY AND HIS NOTION OF EPIGENESIS The writings of William Harvey (1578-1657) on matters of generation, published in 1651, have been analysed by several authors in great detail (e.g. Adelmann, 1966; Pagel, 1967; Gaskin, 1967; Roger, 1971) which is why only the most important points pertinent to the understanding of his theory of epigenesis will be mentioned here. Harvey closely followed Aristotle, as he himself announced, but not in a servile manner, deviating from the thoughts of his master when observation of the developing chick made this necessary. An important point to note is that during medieval times Aristotelian philosophy had become embedded within the Christian tradition of thought and thereby had become mixed with Platonic or Neoplatonic concepts, since Western philosophers took it over from the Islamic invaders of Spain (Gilson, 1955). The soul, which according to Aristotle is the principle of knowledge of the form, immanent in matter (Balss, 1943: 175, 213), is replaced in Harvey’s system by God. The species-specific form is rooted in the eternal world of Divine ideas; the Creator’s providence directs the actualization of this form during embryogenesis. God does so by using the male and female as instrumental causes for generation (Harvey, 1651, transl. by Whitteridge, 1981: 234) and the soul of the fertilized egg as a guiding principle (Harvey, 1651, transl. by Whitteridge, 1981: 139, 216-217) residing in the blood (Harvey, 1651, transl. by Whitteridge, 1981 : 249) which, following Harvey, makes its appearance before the heart in contra-distinction to what Aristotle had said. With God as principle of knowledge of the form we encounter a n element of ‘preformation’, not in its original atomistic meaning but rather in the sense of Divine predetermination of embryonic development: “. . . I have said that it [the cicutriculu, i.e. the blastoderm] is the principal part, as being that in which all the other parts exist potentially, and from whence they later arise, each in its due o r d e r . . .” (Harvey, 1651, transl. by Whitteridge, 1981: 274; see also pp. 450-452). According to Harvey, the egg is a formation de novo; the embryo develops successively, one part after the other, proceeding from the homogeneity of the primordium to the heterogeneity of the adult, which means that the embryo differs at first from the adult condition which it approaches successively. Two mechanisms are invoked by Harvey to explain this developmental process, budding and subdivision: “. . . because it is certain that the chick is built by epigenesis, or the addition of parts budding out from one another. . . the first [part] to exist is the genital part by virtue of which all the remaining parts do later arise as from their first original. . . at the same time that part divides up and forms all the other parts in their due order. . ,” (Harvey, 1651, transl. by Whitteridge, 1981: 240, emphasis added; see also p. 207). The epigenetic process 334 0. RIEPPEL of development is one of vegetation and compartmentalization. One organ formed becomes the material cause of the next one to develop: “. . . the construction. . . begins from some part as from its original, and by its help the other members are produced.. .” (Harvey, 1651, transl. by Whitteridge, 1981: 202). This is quite a striking contrast to the atomistic view of generation, according to which the embryo is built up by the juxtaposition of preformed parts. PRE-EXISTENCE AND THE CORRELATION OF PARTS Charles Bonnet, from Geneva (1720-1 793), had various reasons, predominantly theological and political ones, to defend the hypothesis of preexisting germs (Mam, 1976). Together with Albrecht von Haller (1708-1777) and Lazzaro Spallanzani (1729-1 799) he fought against the rise of materialistic philosophy during the Age of Enlightenment and against the theories of generation which he considered to be derived from that philosophy (Roe, 1981), thereby identifying two rather different models of embryonic development as epigenetic with consequences that will be discussed shortly. One of the many arguments used against epigenesis derived from the functional correlation of the parts of an organism. When Harvey claimed that the parts of the fetus develop one after and out of the other, he could obviously not invoke the functional correlation of these parts as was postulated by Bonnet: the parts of an organism are “SO manifestly linked together and subordinated to one another, that the existence of some presupposes the existence of others” (Bonnet, 1769, Vol. I: 355; see also Bonnet, 1764, Vol. I: 154). Consequently, the entire embryo must pre-exist from the beginning, i.e. from the time of creation (Roger, 1971). The egg, which equals the embryo, is no formation de novo, and therefore the primordium is not homogeneous but heterogeneous, i.e. organized. Development consists of nothing more than the unfolding (or “holution”) of pre-existing parts on the basis of mechanistic secondary causes. Yet Bonnet conceded that the pre-existing parts are not readily visible in the germ at the beginning of its development, and he knew both from the study of insect metamorphosis as well as from Harvey’s (1651), Malpighi’s (Adelmann, 1966) and Albrecht von Haller’s (1758) descriptions of the development of the chick, that the embryo does not resemble the adult but that its parts become visible one after the other and may undergo changes in shape, position and even in function before the adult condition is arrived at (Bonnet, 1764, Vol. I: 292; 1768, Vol. I: 122, 253f Vol. 11: 252fl). To reconcile these observational data with his theory of pre-existence, Bonnet simply avoided the passage from invisibility to non-existence, following the arguments expounded by the “great apostle of the pre-existence of the germs” (Bonnet in Savioz, 1948: 93), P. N. Malebranche, in De la Recherche de la Vkritk. Significantly, when Bonnet turned to a criticism of Harvey (Bonnet, 1764, Vol. I: 155; 1768, Vol. I: 87), he did not blame him for his theory so much as for his descriptions. They both adhered to the concept of an ideal and eternal principle of form, founded in God, who created all organisms each according to its species. As Harvey described the successive development of the parts of the chick, however, he had-according to Bonnet-simply fallen victim to the illusion that what cannot be seen must be ATOMISM AND EPIGENESIS 335 non-existent. If it was not Harvey’s theory, what then was the concept of epigenesis which Bonnet never became tired of attacking? ATOMISM AND EPIGENESIS IN THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY Bonnet’s Considhations sur les Corps Organist%, first published in 1762, was largely composed as a critique of the theories of generation put forward by Georges Buffon ( 1 707-1 788), John Turberville Needham ( 1713-1 78 1 ) and Pierre-Louis Moreau de Maupertuis (1698-1 759), naturalists whom Bonnet correctly identified as admirers of Epicurus. Indeed, atomism enjoyed a vigorous renaissance in the context of enlightened materialism, as is aptly illustrated by d’Holbach’s Systbme de la Nature. What Bonnet objected to was the exclusion of final causes from the interpretation of nature by materialists and the threat of atheism that resulted from such an outlook (letter of Bonnet to Haller dated 11 August 1770; see Sonntag, 1983: 890). No longer was Divine wisdom and foresight responsible for the formation of a viable organism, but rather the fortuitous aggregation of atoms, be it by spontaneous or by sexual generation. If the organism is conceived of as being composed of atoms, the constituent particles become, in principle, interchangeable. T h e atomistic system thus seemed to explain rather easily the problems of inheritance, particularly in cases of hybridization, as well as the origin of malformations. O n the other hand, the observed constancy of the species-specific form could not be explained if the aggregation of atoms during embryogenesis were a process governed by chance alone. This is why most atomists ended up with some kind of vitalism. The ground was prepared by Pierre Gassendi ( 1592-1655) who resurrected atomism as a reaction against Cartesian philosophy (Rod, 1978). According to him, the seminal fluids produced by both sexes consist of atoms derived from the parental bodies; the atoms would combine to form the embryo under the guidance of their soul at the moment of conception. To explain the constancy of the species-specific form, Gassendi was forced to endow the atoms with a soul which would remember their position in the parent body (Adelmann, 1966, Vol. 11: 776-815). H e thus defended some type of vitalistic atomism (Adam, 1955: 16 1- 162), the vitalistic component being derived from an Aristotelian background (Adelmann, 1966, Vol. 11: 802). It is crucial to note that Gassendi postulated not a successive, but an initial and instantaneous combination of the atoms in view of the functional correlation of all the parts of the developing embryo! This is the type of theory which Roger (1971) correctly identified as preformationism. In Buffon’s Histoire des Anirnaux, first published in 1749 in the second volume of his Histoire Naturelle, gktrale et particulilre (Paris, 1749-1 767), the atoms have become the “mol~cules organiques” while the guiding principle for their combination is provided by the famous and obscure “moules inthieurs”. The “molt!cules organiques” were believed to derive from nutritional matter; they would pass through the organs of the adult body where the appropriate form would be ‘imprinted’ on them before they are transported by the blood to the genital organs where they are stored in the seminal fluid. Again, ,the combination of the atoms stemming from the male and female seminal fluids was thought to occur instantaneously at the moment of conception to warrant 336 0. RIEPPEL the functional correlation of at least the ‘essential’ parts of the fetus. Buffon explicitly rejected Harvey’s views on this point, and although he conceded that the embryo has to go through some “dheloppement” before attaining the adult form, his theory clearly qualifies as preformationist (Roger, 1971: 546; see also Bowler, 1973) in spite of the fact that it became widely identified as epigenetic. Maupertuis, on the other hand, admitted the influence of Harvey on his thoughts in the seventh chapter of the first part of his Vknus physique, first published in 1745. He consequently postulated the successive juxtaposition of the (preformed: Hofieimer, 1982: 126) atoms derived from male and female seminal fluids under the influence of purely mechanical forces. Only under the pressure of Reni-Antoine-Ferchault de Riaumur’s ( 1683-4 757) critique (Roe, 1981: 15) would he endow the atoms, in his Syst2me de la Nature (Maupertuis, 1974), with some kind of ‘intelligence’, ‘memory’, ‘appetite’ and ‘aversion’ to explain the constancy of the species-specific form. However, he still considered errors in the combination of the atoms to be possible, which would result in malformations that might even become heritable: the inheritance of polydactyly in the family of Jakob Ruhe, surgeon in Berlin, served as a case in point (Glass, 1968). He finally ended up with the suggestion that new species might have originated in the past by the inheritance of malformations. Although Maupertuis considered himself to be a disciple of Harvey and hence an epigenesist, he grossly misinterpreted his master’s writings, as was in fact noticed by Charles Bonnet ( 1768, Vol. I: 122- 128). Indeed, Maupertuis-like all other atomists-claimed that the embryo forms by the juxtaposition of parts, although he added the qualification that their aggregation occurs successively and not all at once. This model of embryogenesis, resting on the analogy with the formation of a crystal, does not imply the development of the embryo from a homogeneous to a heterogeneous condition, but rather stipulates a mode of growth that was neither admitted by Harvey, nor by another epigenesist of the eighteenth century, Kaspar Friedrich Wolff (1 743-1 794) in his Theorie von der Generation (1764). As compared with Harvey, he qualifies as a vitalist since he put the causa formalis back into matter where Aristotle had it, calling it the vis essentialis. Under the influence of this essential force the embryo would develop from a homogeneous primordium to a heterogeneous condition by a process of ‘vegetation’ (Wolff, 1764: 252): “. . . the different parts develop one after the other, and they develop in such a way that one part is always secreted from or deposited by the other” (Wolff, 1764: 210). Just as in Harvey’s system, one organ formed becomes the material cause of the next one to develop. During the eighteenth century there existed two different models of embryogenesis, both identified as epigenetic by Charles Bonnet and his allies and both, indeed, differing from his own theory of pre-existence by the claim that the embryo was a formation de novo. I n fact, however, only Kaspar Friedrich Wolff qualifies as a true epigenesist in Harvey’s sense. Development starts from a homogeneous primordium, which becomes differentiated by a predetermined, i.e. programmed, process of vegetation, of budding and compartmentalization. In contrast, Buffon, Needham and Maupertuis all qualify as atomists and hence as preformationists in the original sense of the word. They considered the organism as being composed of atoms, derived from the parents’ bodies and passed on by the male and female seminal fluids. These particles were in principle interchangeable, which explained the phenomena of ATOMISM AND EPIGENESIS inheritance in hybrids as well as the origin of malformations-and species. 337 even of new DARWINISM AND ATOMISM Darwin’s theory of evolution was built on two fundamental aspects of nature: variation and natural selection. To explain the phenomena of variation, Darwin developed his theory of pan-genesis which, although construed independently, comes very close to the views of the atomists of the French Enlightenment: “I have read Buffon: whole pages are laughably like mine” (Ch. Darwin in Fr. Darwin, 1887, Vol. 11: 375; see also Bowler, 1974: 175; Mayr, 1982: 694). Darwin claimed that the cells of the adult body would give off invisibly small particles or ‘gemmules’ which represent the material basis for the inheritance of paternal and maternal characteristics. The atomistic background was retained in early Mendelian genetics, as is well documented by the analysis accomplished by Mayr (1982: 707-709, 713-714, 720). In modern population genetics it is the alleles that have become identified as ‘atoms’, and the simple 1 : 1 relationship between hereditary elements and traits of organisms has had to be replaced by elaborate statistical analyses. Nevertheless, the Darwinian or Neodarwinian theory of evolution requires that the organism be viewed in terms of variable traits to which correspond an equally variable genetic basis. T o talk of traits or characters of a n organism means to conceive of it as being composed of parts or ‘atoms’. To exemplify evolution, a canon of comparison of organisms and their traits must be agreed upon. This canon is the principle of homology, an instrument to decompose an organic structure into constituent elements and to compare these in terms of topographical relationships, thus establishing relations of coexistence (topographic homology) and of succession (phylogenetic homology) between these elements or ‘atoms’ on the basis of their connection (Rieppel, 1980, 1985). Naturally, Darwinism or Neodarwinism does not correspond to atomism in its original sense. Traits of an organism may change whereas atoms by themselves were considered immutable. From the viewpoint of genuine atomism, all organismic change was to be related to a changing combination of immutable and undivisible particles. Also, the Neodarwinian view of embryogenesis entails development proceeding from a more or less rigidly mapped or predetermined but macroscopically homogeneous primordium to a heterogeneous adult condition by successive formation of parts. Still, it seems possible to identify an atomistic background of the Neodarwinian view of evolution, both at the genetic and phenotypic level, treating genes and characters as atoms respectively and considering the organism as a particular combination or juxtaposition of these (Webster, 1984). As the atoms are modifiable and interchangeable, the organism can, in principle, vary and become modified in all its details. Gradual, in the sense of continuous (Gingerich, 1984), change, if not necessary, is at least compatible with the atomistic model of evolution. The particular combination of traits or atoms is continually evaluated, as are possible changes in their shape or juxtaposition, by natural selection: every step in a new direction is immediately tested and either admitted and thus made the basis for further change, or else rejected. Viewed from the atomistic perspective, an increase in complexity will be conceived of as an addition of new organs, traits 338 0. RIEPPEL or atoms that open up new ‘faculties’ (e.g. new adaptational options). The paradigm for this concept of increasing complexity is evolution by gene duplication (Ohno, 1970)) coding for new and additional phenotypic traits. THE MODERN CRITIQUE OF DARWINISM One line of argument against the Neodarwinian view of evolution centres on its atomistic background (Webster, 1984). This critique is coupled with the field-theory of ontogenetic development as construed by Goodwin (1984a, b). The development of an organism is no longer viewed as a process of combination of a set of traits or atoms that have so far stood the test of natural selection, and that will be tested again should any kind of change obtain. Rather, embryogenesis is viewed as a creative process which comes close to the original notion of epigenesis. Development proceeds by growth, compartmentalization and differentiation of the initially patterned but macroscopically homogeneous primordium under the guiding influence of morphogenetic fields. The organism resulting from such a developmental process is a “Tout organique” (to use Bonnet’s terminology), subjected to natural selection as a whole and not as a composite of atoms which may change independently from one another. Natural selection loses its function as a guiding force of evolutionary change as the organism loses the capacity to change atomistically or in small steps. Evolutionary change is the result of changing morphogenetic fields which affect orgunique”, that natural selection may either admit or the organism as a LLTo~t eliminate as a whole. As a consequence, homology can no longer mean relations of coexistence and succession of parts or atoms, but in this context must designate shared developmental pathways (Roth, 1984). Finally, increasing complexity will no longer be understood as a result of the addition of new traits, characters or atoms, but rather as an enhanced compartmentalization and differentiation of the initially and macroscopically homogeneous primordium. The evolution of the great diversity of arthropods from a homonomously segmented annelid-like ancestor may serve as a paradigm (Raff & Kaufman, 1983: 25 1-261). There emerges the important theoretical consequence that an epigenetic increase in complexity results from the creative ontogenetic process and does not have to build on foregoing evolutionary steps along the ladder of life. MODERN PREFORMATIONISM Katz & Goffman (1981) have criticized epigenesis by proposing a preformationist model of ontogenetic development. By preformation they understand the determination of conservative topographical relationships or patterns during early ontogenetic stages, “regardless of how these patterns have been generated” (Katz & Goffman, 1981: 443). Their notion of preformation certainly does not match its original atomistic meaning, or the type of preexistence envisaged by Bonnet in an earlier phase of his theorizing. Rather, the authors have identified an early predetermination of the ontogenetic process which proceeds epigenetically. Where Harvey ( 1651) recurred to Divine providence and Wolff ( 1764) to a vis essentialis, Katz & Goffman ( 1981) invoke some genetic or cytoplasmic patterning of the zygote. The closeness of this ATOMISM AND EPIGENESIS 339 system of thought to Bonnet’s theory of pre-existence is once more illustrated by Bonnet’s designation of the germ as an “organized fluid” at a later stage of the development of his theory (Bonnet, 1768, Vol. 11: 118). On the other hand, the ‘genetic potential hypothesis’ proposed by Schwabe & Warr (1984) qualifies as a theory of pre-existence not at the phenotypic but at the genotypic level. According to these authors evolution loses its emergent aspect and consists of nothing more than the successive actualization of genetic information pre-existent since the beginning of life on this earth. In a similar vein, Bonnet had envisaged a series of encapsulated “germs of resurrection” from which new (but pre-existent) phenotypes would develop in the course of a series of earthly revolutions that would alter the conditions of life on the surface of the earth (Bonnet, 1769). The only problem was to explain how the successively actualized organisms (of increasing complexity) would be adapted to the changing environmental conditions. Bonnet had to recur to Leibnitz’ theory of pre-established harmony and to postulate that Divine providence had not only fore-ordained the environmental effects of the successive earthly revolutions but also the sequence of actualization of the encapsulated germs at the moment of Creation. The adaptation of the pre-existent organisms to changing environmental conditions was thus pre-established. I t will be interesting to see how Schwabe & Warr (1984) are going to explain the adaptation of organisms to changing environmental conditions during evolution by the successive actualization of pre-existing genetic programmes. ATOMISM VERSUS EPIGENESIS Drawing on the analogy to the formation of crystals, atomists had described the process of embryogenesis as one of juxtaposition and coalescence of modifiable and interchangeable parts. Epigenesists such as William Harvey or K. F. Wolff emphasized that ontogenetic development produces complexity and diversity from a homogeneous primordium by the emergence of one structure from another. Development entails growth (“budding”, “vegetation”) and compartmentalization or subdivision. Attempting a synthesis one might claim that growth, compartmentalization, subdivision and coalescence are all to be treated as attributes of an emergent developmental process, of which the polyp (Hydra) has been evoked as paradigm by the various schools of thought ever since the discovery of its reproductive and regenerative capabilities by Abraham Trembley in the years 1740-1 741. Such an amended notion of epigenesis still transcends atomism in an important aspect, however: it entails a principle of individuation! In the context of atomism, an organism represents nothing more than the passing aggregation of atoms exposed to the contingencies of fundamental and random variation accumulating from a historical process-everything is in flux: “Naitre, vivre et passer, c’est changer de formes . . .”, writes Denis Diderot in his Le Rtve d‘dlembert (1769). Not only is this view of life compatible with Darwin’s adherence to “that old canon in natural history of natura non fucit saltum”, but if extrapolated beyond the taxic level of the organism in the hierarchy of nature, it must lead to a nominalistic species concept, as indeed is documented in Darwin’s writings (see Mayr, 1982: 267). The epigenetic or generative paradigm, on the other hand, emphasizes the 340 0. RIEPPEL uniqueness and individuality of each organism, of each ‘‘Tout orgunique”: each form is created anew during ontogeny, complexity emerging from homogeneity, the more specialized diverging from the more generalized. Ontogeny corresponds to a process of individualization: “the ontogenetic development of an individual corresponds to the growth of individuality in every respect”, wrote the epigenesist K. E. von Baer (1828: 263). The programme of the developmental process, genetic and epigenetic factors of canalization versus developmental plasticity, determines the potentialities of the individual which become actualized during ontogeny, and hence represents the principle of individuation: it represents an element of ‘being’ in the process of ‘becoming’. Gould (1983: 326-363) and Webster (1984: 206) have extrapolated this principle of individuation beyond the taxic level of the organism, and have consequently arrived at an essentialistic species concept. Distinct gaps between classes of essentially similar tissues, organs or organisms are bridged by a hypothesis of dichotomously organized developmental pathways. (See Raff & Kaufman (1983) and Arthur (1984) for the role played by homoeotic mutations in development and evolution, as well as Osborn (1984) for an example concerning the dentition of reptiles and mammals.) Homologies do not concern separate traits but developmental pathways (Roth, 1984). Shared developmental pathways are said to characterize species and higher taxa, and are considered as “real essences”, the characters they determine being “nominal essences’’ of taxonomies (Webster, 1984: 206). The extrapolation of the epigenetic or generative paradigm to supraindividual levels of the taxic hierarchy logically results in a break with the principle of continuity and in a theory of saltatory evolutionary change corresponding to a pattern of a dichotomously organized hierarchy of nature. The current debate on the tempo and mode of evolution can thus be traced back to contrasting paradigms of ontogenetic development. In view of the uniqueness and individuality of each “ Tout orgunique” it must be borne in mind, however, “that the relation of homology appears to be a category of the mind only . . . to search in nature for homology is as futile as to search for identity” (Nelson, 1970: 378). Homologies, whether they refer to separate traits or to developmental pathways, entail the abstraction of universals from particulars in order to reduce the multiplicity of appearances to a unified hierarchy of nature. Atomism versus epigenesis, continuity versus discontinuity, gradualism versus punctualism, process versus pattern, represent different ways of abstraction of universals from individuals, and represent different ways of looking at nature (Rieppel, 1985), or, in Gould’s (1982: 137) words: different ways of seeing. REFERENCES ADAM, M., 1955. L’intluence posthume. In Piewc Gassmdi 1592-1655. Sa Vie ct son Oeuvre: 157-182. Pans: A. Michel. ADELMANN, H. B., 1966. Marcello Malpighi and the Evolution of Embryology. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ARTHUR, W., 1984. Mechanism of Morphological Euoluiion. London: John Wiley & Sons. BALSS, H. (Ed.), 1943. Arisioiclcs Biologische Schrzzten. Muiichen: Ernst Heirneran. BONNER, J. T. (Ed.), 1982. Euoluiion and Dcuelopmni. Berlin: Springer Verlag. BONNET, Ch., 1764. Contmplaiion de la nature, 2 vols. Amsterdam: Marc-Michel Ray. BONNET, Ch., 1768. Conridtraiionr sur 1 s Corps Organists, 2 vols, 2nd edition. Amsterdam: Marc-Michel Ray. BONNET, Ch., 1769. La Palinglnlsic Philosophiquc, 2 vols. Geneva: C. Philibert & B. Chirol. ATOMISM AND EPIGENESIS 34 1 BOWLER, P. J., 197 1. Preformation and pre-existence in the seventeeth century: a brief analysis. Journal of the History of Biology, 4: 22 1-244. BOWLER, P. J., 1973. Bonnet and Buffon; theories of generation and the problem of species. Journal of the History of Biology, 6: 259-28 1. BOWLER, P. J., 1974. Evolutionism in the Enlightenment. History of Science, 12: 159-183. DARWIN, Ch., 1868. The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication, 2 vols. London: John Murray. DARWIN, Fr., 1887. The Life and Letters of Charles Darwin, 3 vols, 3rd edition. London: John Murray. GASKIN, E. B., 1967. Investigations into Generation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. GILSON, E., 1955. History of Christian Philosophy in the Middle Ages. London: Sheed and Ward. GINGERICH, P. D., 1984. Punctuated equilibria-where is the evidence? Systematic <oology, 33: 335-338. GLASS, B., 1968. Maupertuis, pioneer of genetics and evolution. In B. Glass, 0. Temkin & W. L. Straus Jr (Eds.), Forerunners of Darwin 17451859: 51-83. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Paperbacks. GOODWIN, B. C., 1984a. A relational or field theory of reproduction and its evolutionary implications. In M.-W. Ho & P. T. Saunders (Eds.), Beyond Neo-Darwinism: 219-241. London: Academic Press. GOODWIN, B. C., 1984b. Changing from an evolutionary to a generative paradigm in biology. In J. W. Pollards (Ed.), Evolution: Paths into the Future: 99-120. Chichester and New York: John Wiley & Sons. GOULD, S. J., 1982. Punctuated equilibrium-a different way of seeing. New Scientisf, 94: 137-141. GOULD, S. J . , 1983. Irrelevance, submission and partnership: the changing role of paleontology in Darwin’s three centennials and a modest proposal for macroevolution. In D. S. Bendall (Ed.), Evolution from Molecules to Man: 347-366. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. HALLER, A. VON, 1758. Sur la Formation du Coeur dans le Poulet. Lausanne: Marc-Michel Bousquet. HARVEY, W., 1651 (1981). Disputatiom Touching the Generation of Animals. Translated with introduction and notes by G. Whitteridge. London: Blackwell. HOFFHEIMER, M. H., 1982. Maupertuis and the eighteenth-century critique of preexistence. Journal of the History of Biology, 15: 1 19-144. KATZ, M. J. & GOFFMAN, W., 1981. Preformation of ontogenetic patterns. Philosophy of Science, 48: 438-453. KULLMANN, W., 1979. Die Teleologie in der aristotelischen Biologie. Heidelberg: Carl Winter Universitatsverlag. MARX, J., 1976. Charles Bonnet contre les Lumieres 1738-1850. Studies on Voltairc and the Eighteenth Century, 156157: 1-782. MAUPERTUIS, P.-L. M. DE, 1974. Systkme de la nature. In Oeuvres de Maupertuis, vol. 2. Hildesheim: Georg Olms Verlag. MAYR, E., 1982. The Growth of Biological Thought. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. NELSON, G. J., 1970. Outline of a theory of comparative Biology. Systematic .Zoology, 19: 373-384. OHNO, S., 1970. Evolution by Gene Duplication. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer Verlag. OSBORN, J. W., 1984. From reptile to mammal: evolutionary considerations of the dentition with emphasis on tooth attachment. In M. W. J. Ferguson (Ed.), The Structure, Development and Evolution of Reptiles: 549-574. London: Academic Press. PAGEL, W., 1967. William Harvey’s Biological Ideas. Selected Aspects and Historical Background. Basel and New York: S. Karger. RAFF, R. A. & KAUFMAN, T. C., 1983. Embryos, Genes, and Euolution. New York: Macmillan. REGNkLL, H., 1967. Ancient Views on the Nature ofLife. Lund: C. W. K. Gleerup. RIEPPEL, O., 1980. Homology, a deductive concept? ZeitschriJ f u r eoologische Systematik und Evolutionsforschung, 18: 315-319. RIEPPEL, O., 1985. Muster und Prozess: Komplementaritat im biologischen Denken. Naturwissenschaften, 72: 337-342. ROD, W., 1978. Geschichte der Philosophie, Band VII. Die Philosophie der Neuzeit I . Von Francis Bacon bis Spinoza. Miinchen: C. H. Beck. ROE, S. A., 1981. Matter, Life and Generation. Eighteenth-Century Embryology and the Haller- Wolff Debate. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ROGER, J., 1971. Les Sciences de lo Vie dans la PensCe Frangaise du X V I I I e Si2cle. Paris: Armand Colin. ROSENBERG, A., 1985. The Structure of Biological Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ROTH, V. L., 1984. On homology. Biological Journal of the Linnean Sociely, 22: 13-29. SAVIOZ, R. (Ed.), 1948. Les Mimoires Autobiographies de Charles Bonnet de Gendue. Paris: Librairie Philosophique J.Vrin. SCHWABE, C. & WARR, G. W., 1984. A polyphyletic view of evolution: the genetic potential hypothesis. Perspectiues in Biology and Medicine, 27: 465-483. SONNTAG, 0. (Ed.), 1983. The Correspondence between Albrecht von Haller and Charles Bonnet. Bern: Hans Huber. VON BAER, K. E., 1828. Ueber Entwickelungsgeschichte der Thiere. Beobachtung und ReJexion. I. Theil. Konigsberg: Gebr. Borntrager. WEBSTER, G., 1984. The relations of natural forms. In M.-W. Ho & P. T . Saunders (Eds), Beyond NeoDarwinism: 193-2 17. London: Academic Press. WILKIE, J. S., 1967. Preformation and epigenesis: a new historical treatment. History of Science, 6: 138-150. WOLFF, K. F., 1764. Theorie uon der Generation in t w o Abhandlungen. Berlin: Friedrich Wilhelm Birnstiel.