* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The US Dollar and the Euro as International

Foreign exchange market wikipedia , lookup

Foreign-exchange reserves wikipedia , lookup

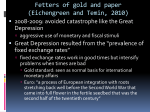

Bretton Woods system wikipedia , lookup

Currency war wikipedia , lookup

Fixed exchange-rate system wikipedia , lookup

Currency War of 2009–11 wikipedia , lookup

Exchange rate wikipedia , lookup

International monetary systems wikipedia , lookup

Currency intervention wikipedia , lookup

Reserve currency wikipedia , lookup

International status and usage of the euro wikipedia , lookup