* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Torah Rediscovered - Hebraic Roots Teaching Institute

Supersessionism wikipedia , lookup

Jewish views on astrology wikipedia , lookup

Homosexuality and Judaism wikipedia , lookup

Index of Jewish history-related articles wikipedia , lookup

Jewish views on sin wikipedia , lookup

Three Oaths wikipedia , lookup

Origins of Rabbinic Judaism wikipedia , lookup

Jonathan Sacks wikipedia , lookup

Ayin and Yesh wikipedia , lookup

Priestly covenant wikipedia , lookup

Jewish views on religious pluralism wikipedia , lookup

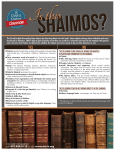

Torah scroll (Yemenite) wikipedia , lookup

Jewish views on evolution wikipedia , lookup

Mishneh Torah wikipedia , lookup

Torah im Derech Eretz wikipedia , lookup

Jewish schisms wikipedia , lookup