* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download A Developmental History of the Hispano-Romance Verb

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

A Developmental History of the Hispano-Romance Verb Conjugations

Dissertation

Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy

in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University

By

Thomas William Stovicek, M.A.

Graduate Program in Spanish and Portuguese

The Ohio State University

2010

Dissertation Committee:

Wayne J. Redenbarger, Advisor

Fernando Martínez-Gil

David Odden

Copyright by

Thomas William Stovicek

2010

Abstract

This study outlines the development of Portuguese and Spanish verbal morphology from

Latin in the context of the Hispanic branch of Romance, with a focus on the

conjugational classes, whose number has been reduced to only three in this branch of

Western Romance. It is innovative in approaching the topic as a study of sequential

productive grammars in an Item and Process type framework. We have found evidence

to indicate that in addition to regular phonological change, morphological restructuring

and language contact each played an important role in the reclassification of the Latin

verb classes II-IV into the verb classes of the Hispano-Romance daughter languages. The

historical data studied have been collected from published secondary sources of

manuscript and dialectological data and supplemented with data from searchable

electronic corpora.

ii

Dedication

Dedicated to my wife, Vanessa, who is my soulmate, best friend and greatest inspiration

iii

Acknowledgments

I wish to acknowledge all the outstanding faculty and staff of The Department of Spanish

and Portuguese and The Department of Linguistics at The Ohio State University who

have aided, taught, inspired and elightened me these past 10 years, and especially Dr.

Wayne J. Redenbarger who has been not only an incredible teacher and dedicated mentor

for many years, but also a dear friend. I also wish to acknowledge the College of Arts and

College of Humanities and the Post-Prospectus Fellowship which greatly facilitated the

completion of this dissertation. And of course, I must aknowledge my dear and beloved

family whose unfaltering love and patience form a network of support without which I

could never find the courage to follow my dreams.

iv

Vita

2000………………………………………... Indian Valley High School

2004………………………………………... B.A. Portuguese, With Distinction, The

Ohio State University

2004………………………………………... B.A. Spanish, With Honors, The Ohio

State University

2004 to present…………………………….. Graduate Teaching Associate, Department

of Spanish and Portuguese, The Ohio State

University

2006………………………………………... M.A. Spanish and Portuguese - Hispanic

Linguistics, The Ohio State University

Publications

Stovicek, Thomas. 2004. A Sociolinguistic Analysis of the Factors Resulting in the

Successful Imposition of the Portuguese Language in Brazil. Precedings of the

National Conference on Undergraduate Research, 2004.

v

Nazareth Soares Fonseca, Maria. 2007. Master Tamoda and His Adventures in Language.

Research in African Literatures. Trans. Thomas Stovicek. 38.1: 75-86.

Assis Duarte, Eduardo de. 2007. Machado de Assis's African Descent. Research in

African Literatures. Trans. Thomas Stovicek. 38.1: 134-151.

Fields of Study

Major Field: Spanish and Portuguese

Hispanic Linguistics

Historical Romance Linguistics

Phonology and Morphology

Language Change

Language Contact

Dialectology

vi

Table of Contents

Abstract .......................................................................................................................... ii

Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................... iv

Table of Contents ......................................................................................................... vii

List of Tables................................................................................................................. ix

List of Figures ............................................................................................................... xi

List of Abbreviations .................................................................................................... xii

Chapter 1: Introduction ....................................................................................................1

Chapter 2: Verbal Morpho-phonology of Classical Latin .................................................7

Chapter 3: Historical Morphology and Phonology in Generative Grammar .................... 24

Chapter 4: Relevant Phonological Changes in the Vulgar Latin of the Iberian Peninsula 34

Chapter 5: Historical Data from Hispano-Romance ....................................................... 46

Chapter 6: Relevant Changes in the Morpho-phonology of the Hispano-Romance

Languages ..................................................................................................................... 57

Chapter 7: Summary and Conclusions ........................................................................... 85

References ..................................................................................................................... 93

Appendix A: Color key to Classical Latin and Hispano-Romance verb data................... 97

Appendix B: CL simple verbs with Modern Spanish and Portuguese Reflexes ............... 98

vii

Appendix C: CL compound prefixed verbs and Modern Spanish and Portuguese Reflexes

.................................................................................................................................... 103

viii

List of Tables

Table 1.1. Modern Castilian and Portuguese cognate verbs which disagree in conjugation

membership. ....................................................................................................................4

Table 2.1. Minimal pairs in CL based on contrastive vowel length, from Penny (2002:

45). ..................................................................................................................................9

Table 2.2. The four CL conjugation classes according to the traditional classification. ... 10

Table 2.3. Differences in the paradigms of CL conjugations III and IIIi in the present

active tense. Adapted from Anderson (1978: 174,176). .................................................. 11

Table 2.4. The CL conjugation classes according to Hall (1983:179). ............................ 12

Table 2.5. The CL Conjugation classes following Redenbarger (1976). ......................... 13

Table 2.6. Two third declension neuter nouns, from Redenbarger (1976: 2). .................. 15

Table 2.7. /ĭ/-epenthesis in third declension nouns. ........................................................ 16

Table 2.8. Application of CL rhotacism and vowel-lowering in the inflection of corpus.17

Table 3.1. The present indicative paradigm of the Modern Castilian verb perder „to lose‟.

...................................................................................................................................... 28

Table 3.2. The present indicative paradigm of the Old French verb amer „to love‟. ........ 28

Table 3.3. The present indicative paradigm of the Modern French verb aimer „to love‟. 29

Table 3.4. Innovative weak preterites in Aragonese and their standard Castilian

equivalents. ................................................................................................................... 30

ix

Table 4.3. The merger of CL vowels in HR tonic position.............................................. 39

Table 4.4. The merger of CL vowels in HR atonic position. ........................................... 39

Table 4.5. The merger of CL vowels in HR word-final atonic position. .......................... 40

Table 4.6. The predicted reclassification of the CL verb conjugations in HR based on

regular sound change. .................................................................................................... 45

Table 5.1. Past Perfect Stem Classification (Perfect Type) ............................................. 52

Table 5.2 Perfect Participle Classification (Part. Type) .................................................. 52

Table 6.1. Latinisms in Castilian taken from the Latin second conjugation .................... 67

Table 6.2. Latinisms in Portuguese taken from the Latin second conjugation ................. 68

Table 6.3 Some Latinisms in Castilian taken from the Latin third (athematic) conjugation

...................................................................................................................................... 74

Table 6.4 Some Latinisms in Portuguese taken from the Latin third (athematic)

conjugation .................................................................................................................... 75

Table 6.5 Some Portuguese Latinisms from the Latin third (athematic) conjugation

alongside their Galician cognates. .................................................................................. 76

x

List of Figures

Figure 4.1. The Vulgar Latin vowel inventory as described by many traditional accounts.

...................................................................................................................................... 35

Figure 4.2. The Vulgar Latin surface vowels before the loss of the length distinction. .... 36

Figure 4.3. The Vulgar Latin inventory of vocalic phonemes after the loss of the length

distinction. ..................................................................................................................... 37

Figure 5.1. A sample view of the spreadsheet in Microsoft Excel 2007. ......................... 56

xi

List of Abbreviations

1SG: first-person singular

1PL: first-person plural

2PL: second-person plural

ant.: antiquated

atr: advanced tongue root

C: consonant

Cast.: Castilian

CdE: Corpus del español

CdP: Corpus do português

CL: Classical Latin

DRAE: Diccionario de la Real Academia Española

HR: Hispano-Romance

Mod.: Modern

PLD: Primary linguistic data

Port.: Portuguese

rtr: retracted tongue root

RV: root-vowel

TV: theme-vowel or thematic vowel

V: vowel

xii

Chapter 1: Introduction

All students of the Spanish and/or Portuguese languages are familiar with the

three conjugation classes, although they may not all know them by that term. Textbooks

for teaching Spanish or Portuguese as a foreign language divide verbs into the groups: “ar verbs”, “-er verbs” and “-ir verbs”, based on the vowel found before the final –r which

is characteristic of verb infinitives in these languages. These groupings hold the key to

learning a large portion of the inflectional morphology of verbs in these languages

because choosing the “correct” inflectional ending often depends on the group to which

the verb belongs. These groupings are also frequently referred to by number, where the –

ar verbs constitute the “first conjugation”, the –er verbs the “second conjugation” and the

–ir verbs the “third conjugation”.

Spanish and Portuguese are both members of the Hispano-Romance language

family, which in turn is a branch of the Romance family of languages; a branch of the

Indo-European language family. The Hispano-Romance family of languages includes the

languages which developed from Latin as it was spoken in the Iberian Peninsula, the

geographic location of modern-day Spain and Portugual. Although Spanish and

Portuguese are, by far, the most widely spoken languages in this family, they are just two

of its members. Galician, Leonese, Asturian and Aragonese are also represented by a

significant body of literature and continue to be spoken natively (often alongside

1

Castilian) by regional populations in Spain. From here on, I will primarily use the name

Castilian in reference to the national language of Spain, and that which is spoken

throughout Spanish-speaking Latin America and elsewhere in former territories of Spain.

This is simply to distinguish this variety from the other Romance varieties which are also

native to Spain. Catalan is a Romance language which is spoken along the eastern coast

of the Iberian Peninsula and along the Spanish border with France. Some scholars of

Romance linguistics group Catalan together with the Hispano-Romance languages as part

of the Ibero-Romance family of languages. However, Catalan shares certain structural

characteristics with languages of the Gallo-Romance family (of which French is a

member), and so other scholars prefer not to group it with Hispano-Romance, but rather

(along with Occitan) in a separate family which is neither Hispano-Romance, nor GalloRomance. Due to some of these structural differences, especially as they relate to the verb

conjugations which are the focal point of the present study, Catalan will not be given

extensive consideration here.

Latin is generally described as having four conjugation classes (see Chapter 2).

Among the Romance languages, only those of the Hispano-Romance subfamily have

completely reduced their conjugation classes, completely eliminating the stress pattern

once characteristic of Latin conjugation-III verbs, to just three conjugations. This

development sets the Hispano-Romance (HR) languages apart from the rest of Romance

in terms of verbal morphology.

Despite the common origin and close relationship between the HR languages, if

we make a comparison of cognate verbs between any two of them, we will quickly notice

that a number of verbs differ in their conjugation class membership. Table 1.1 lists a

2

number of Castilian and Portuguese verbs that differ in this manner along with their Latin

etymons.

Latin Verb

Modern Castilian

Modern Portuguese

fervēre

hervir

ferver

possidēre

poseer

possuir

morī

morir

morrer

percipĕre

percibir

perceber

tussīre

toser

tossir

bat(t)(u)ĕre

batir

bater

cadĕre

caer

cair

constringĕre

costreñir / costriñir

constranger

deterĕre (reterĕre)

derretir

derreter

dīcĕre

decir

dizer

ēligĕre

elegir/eligir

eleger

ērigĕre

erigir / erguir

erguer

exprimĕre

exprimir

espremer / exprimir

fervĕre

hervir

ferver

gemĕre

gemir

gemer

occurrĕre

ocurrir

ocorrer

expellĕre

expeler

expelir

repoenitĕre

repentirse / arrepentirse

arrepender-se

praedīcere

predecir

predizer

reddĕre (rendĕre?)

rendir / render

render

regĕre

regir

reger

requīrĕre

Continued

requerir

requerer

3

Table 1.1 continued

scrībĕre

escribir

escrever

tangĕre

tangir

tanger

convertĕre

convertir

converter

vīvĕre

vivir

viver

sufferre

sufrir

sofrer

Table 1.1. Modern Castilian and Portuguese cognate verbs which disagree in conjugation

membership.

These differences pose an interesting problem for historical linguistics. If we take

into account only the regular sound changes which are known to have taken place in

Hispano-Romance during development of this language family from Latin (see Chapter

4), the above-illustrated differences in conjugation come as a surprise. Therefore, the data

suggest that the evolution of the Hispano-Romance verbs is more complex than what can

be accounted for by historical phonology alone.

The reduction of the conjugation classes in number, from four to three, in

Castilian has been previously discussed by a number of linguists. The process has

generally been described as a collapse of Latin conjugations II and III along with the

movement of some of these verbs (primarily from conjugation III) to conjugation IV.

Several studies have also emphasized the importance of the role played by the stem

vowel (or root vowel) in the reclassification of verbs in Castilian. It has been claimed that

the –er conjugation excluded all verbs with high stem vowels, whereas all verbs of the –ir

4

conjugation include some forms with high stem vowels. Verbs with the stem vowel /a/

are considered “neutral” in this process (Lloyd 1986: 283).

Far less attention has been given to the reduction of the conjugation classes and

the reclassification of affected verbs in the other HR languages. However, a brief look at

data like that given above in Table 1.1 shows that the process must have varied between

varieties of Hispano-Romance. This fact alone warrants a new study of this change from

a wider perspective which incorporates data from throughout the Hispano-Romance

language family.

Furthermore, some linguists have challenged the traditional description of the

Latin verb conjugation system (see Chapter 2). These analyses, especially that of

Redenbarger (1976), posit an athematic verb conjugation which lacks the underlying

theme vowel which is central to the distinction between verbs in the traditional fourconjugation description of the Latin verb system. A thorough study of the development of

the Hispano-Romance verb conjugations that takes into account this finding regarding the

morpho-phonology of Latin has not previously been undertaken.

This dissertation describes the findings of such a study. The study traces the

development of the three-conjugation system of the Hispano-Romance language family

from the five-conjugation system of Classical Latin described by Redenbarger (1976)

with attention to how the system of productive morpho-phonological rules changed from

one stage of the language to another, and to how the overall development of the system

varied between varieties within the language family. The results of this study strongly

suggest that, in addition to regular phonological change, morphological restructuring and

5

language contact were instrumental in shaping the verb conjugations of the HR

languages.

6

Chapter 2: Verbal Morpho-phonology of Classical Latin

Latin is the ancestor of Spanish, Portuguese and all other Romance languages.

The Romance languages are Latin as it continues to be spoken today in the diverse and

far-reaching territories of the Romance-speaking world. “[T]here is an unbroken chain of

speakers, each learning his or her language from parents and contemporaries, stretching

from the people of the Western Roman Empire two thousand years ago to the present

population of the Spanish-speaking world (Penny 2002: 4),” and the same can easily be

said of Portuguese and the other Hispano-Romance varieties. Although it has been

recognized since at least the nineteenth century that the Romance languages do not

exactly descend from Classical Latin (the literary language), but rather from spoken, nonliterary varieties (referred to collectively as Vulgar Latin) (Penny 2002: 4), the study of

Classical Latin still plays a key role in our understanding of the history of the Romance

languages. This is simply due to the fact that the knowledge we have of Vulgar Latin is

fragmentary and incomplete in comparison to the wealth of data preserved in the

Classical Latin texts. “There can be no such thing as a „Vulgar Latin text‟. Texts of all

kinds are composed, by definition, by the educated and therefore in the codified or

„standard‟ variety of Latin in which such writers have inevitably been trained (Penny

2002: 6).” Latin was a member of the Italic branch of Indo-European, and was spoken

originally in a small area around the mouth of the Tiber known as Latium (Hall 1974:

7

47). All languages have some degree of variation between speakers, and Latin cannot

have been an exception. As it spread across the vast Roman Empire, the diversity of oral

expression from one geographic region to another increased as well. The separation

between the literary standard and the popular, spoken language became more marked in

the first century B.C. Classical Latin thenceforth became more and more static, while

popular speech continued to develop more-or-less independently (Hall 1974: 71).

Classical Latin can be seen as the best-documented evidence we have of the historical

roots shared by all Romance languages, while at the same time it must be recognized that

significant (though scarcely documented) change and diversity had already developed in

the spoken variety (or varieties) of Latin long before the appearance of the first Romancelanguage texts. Despite the fact that there is a considerable gap in the data regarding the

stages and varieties of the language that lie between Classical Latin and any of the

Romance languages, the division between Classical Latin and Vulgar Latin should not be

over-exaggerated. “Whatever the influences which have come to bear on the Romance

languages during the course of their history, their most prominent feature is an abiding

Latinity. From Latium came virtually all their structure and by far the greater part of their

vocabulary (Elcock 1960: 18).”

The remainder of the present chapter will constitute an attempt to summarize

those aspects of Classical Latin morpho-phonological structure that are essential in order

to contextualize the discussion of the historical development of the conjugation classes of

Hispano-Romance that will follow in the subsequent chapters of this dissertation.

8

The Latin vowel system

Classical Latin distinguished between five vowels in terms of articulation. The CL

vowel system was also sensitive to quantity, such that there was a phonemic distinction

between long and short vowels (henceforth represented in the traditional way by the

presence of brevs and macrons respectively). Thus, there were a total of ten vocalic

phonemes in the in the CL system: /ă/, /ā/, /ĕ/, /ē/, /ĭ/, /ī/, /ŏ/, /ō/, /ŭ/ and /ū/.

The phonemic distinction made between long and short vowels can be illustrated

by the existence of minimal pairs such as those given in Table 2.a.

Long vowel

Short vowel

HĪC „here‟

LĪBER „free‟

LĒVIS „smooth‟

VĒNIT „he came‟

MĀLUM „apple‟

ŌS „mouth‟

PŌPULUS „white poplar‟

HĬC „this‟

LĬBER „book‟

LĔVIS „light in weight‟

VĔNIT „he comes‟

MĂLUM „evil, misfortune‟

ŎS „bone‟

PŎPULUS „people‟

Table 2.1. Minimal pairs in CL based on contrastive vowel length, from Penny (2002:

45).

Of the many diphthongs which existed in the oldest Latin texts, only three are

preserved in the literary texts of Classical Latin. These are [aj], [oj] and [aw] (spelled ae,

oe and au respectively) (Elcock 1960: 43).

9

The Conjugation Classes

Traditional descriptions of the Classical Latin conjugations (Anderson 1979,

Lloyd 1987, Penny 2002, Williams 1962, and others) indicate four distinct thematic

classes of verbs, distinguished by a thematic vowel appearing in the present active

infinitive form of the verb. These are shown in Table 2.1 with representative verb forms.

CL Conjugation

Theme vowel

Present, active

infinitive form

I

/ā/

cantāre

II

/ē/

vidēre

III

/ĕ/

perdĕre

IV

/ī/

sentīre

Table 2.2. The four CL conjugation classes according to the traditional classification.

As Table 2.2 illustrates, conjugations I, II and IV were characterized by the

phonemically long vowels /ā/, /ē/ and /ī/ respectively, whereas conjugation III was

characterized by the short vowel /ĕ/. It is also customary to distinguish between two

subgroups of conjugation III, according to certain differences in the surface paradigms of

these verbs as exemplified in Table 2.3 below.

10

Infinitive

perdĕre

(III)

fugĕre

(IIIi)

1SG

perdō

perdam

fugiō

fugiam

2SG

perdis

perdās

fugis

fugiās

3SG

perdit

perdat

fugit

fugiat

1PL

perdimus

perdāmus

fugimus

fugiāmus

2PL

perditis

perdātis

fugitis

fugiātis

3PL

perdunt

perdant

fugiunt

fugiant

Mood

Indicative

Subjunctive

Indicative

Subjunctive

Table 2.3. Differences in the paradigms of CL conjugations III and IIIi in the present

active tense. Adapted from Anderson (1978: 174,176).

We can see from the examples in table 2.3 that conjugation IIIi differs from III by

the presence of an ĭ before the 1SG marker –ō a well as before the subjunctive marker -āthroughout the paradigm. Therefore, conjugation IIIi is generally treated as an irregular

subgroup of the verbs in conjugation III due to the identical vowels appearing in the

theme-vowel position in the surface forms of their present active infinitive forms and the

overall similarity of their surface forms in the present indicative active and other

paradigms.

Although this traditional classification of the CL verb conjugations continues to

be accepted by most scholars of Latin, and remains the standard model for use in the

11

teaching of Latin, some linguists have challenged the validity of the traditional analysis,

and have suggested alternative interpretations of the CL verb data. Hall claims that the

traditional presentation of the conjugation scheme errs in a number of ways. According

to his analysis, the dependence on the comparison of the present active infinitive to the

first person singular present active indicative as a basis for classifying verbs is

inadequate. He posits three theme vowels /a/, /e/, and /i/, each of which can be either

long or short, in addition to a zero theme (1983: 179). His classification is summarized in

Table 2.4.

Conjugation

I

a

b

II

a

b

III

a

b

IV

‘Stem’(Theme)-Vowel

ā

ă

ī

ĭ

ē

ĕ

Ø

Example stem

[kanta:] „sing‟

[da] „give‟

[dormi:] „sleep‟

[kapi] „seize‟

[kale:] „heat‟

[rege] „rule‟

[es] „be‟

Table 2.4. The CL conjugation classes according to Hall (1983:179).

Hall bases his classification on differences in the overall paradigms of the verbs

given in his table, rather than on the present active infinitive and the first person singular

active indicative. Unfortunately however, he does not otherwise offer any argument as to

the superiority of his analysis over the traditional classification. Some weaknesses in his

analysis are revealed when we consider that first, his /ă/-theme conjugation and Ø-theme

conjugation can be exemplified by just one verb each (DĂRE and ESSE, respectively)

and that each of these has long been recognized as irregular. While DĂRE agrees with

the CL conjugation I in most forms, its older compounds share forms with CL

12

conjugation III (Kent 1946: 100). ESSE, on the other hand, is an irregular verb in all of

the Indo-European language family, and varies in its morphology from all of the

conjugation classes (Moreland & Fleischer 1977: 25). Furthermore, Hall fails to account

in any way for the allophony of [ĕ] and [ĭ] in TV position in his /ĕ/-theme and /ĭ/-theme

conjugation classes. Let us now turn to yet another alternative analysis of Classical Latin

verb morphology.

Conjugation

T.V.

Infinitive

2SG pres. ind.

act.

2SG pres. sub.

act.

I

[ā]

laudāre

laudās

II

[ē]

monēre

monēs

III

Ø

dūcere

dūcis

IIIi

[ĭ]

capere

capis

IV

[ī]

audīre

audīs

laudēs

moneās

dūcās

capiās

audiās

Table 2.5. The CL Conjugation classes following Redenbarger (1976).

Redenbarger (1976) posits a five-conjugation system for Latin which is shown

above in Table 2.5. Unlike Hall (1983), Redenbarger makes a strong argument for his

classification based on an analysis of allomorphic alternations throughout the inflectional

morphology of the language, and a set of synchronic morpho-phonological rules and

abstract underlying representations for the surface forms. His classification is supported

by two productive rules which he posits for the synchronic grammar of Classical Latin.

13

2.1) Vowel-lowering: Underlying short high vowels are lowered preceding an [ɾ] or

word-finally.

V[-long] → [-high]/__{[ɾ], #}

2.2) /ĭ/-epenthesis: An /ĭ/ is inserted to break up consonant clusters across a morpheme

boundary.

Ø → /ĭ/ /C__+C

Along with some widely-accepted phonological rules such as the vocalis ante vocalem

corripitur rule (shown in 2.3) and a few others cited in his appendix (such as those shown

in 2.4-2.6), these synchronic rules cleanly account for the surface paradigms of all five of

the conjugations proposed in his classification.

2.3) vocalis ante vocalem corripitur: A long vowel is shortened in pre-vocalic position.

V[+long] → [-long] /__V

2.4) la loi des mots iambes: A long vowel is shortened in the second syllable of a bisyllabic word. (Ordered after vowel-lowering, this rule explains why ubi „where‟ or nisi

„if not‟ are not counter-examples to vowel lowering.)

V[+long] → [-long]/ #CVC__#

14

2.5) Vowel shortening before word-final stop consonants.

V[+long] → [-long]/__C[-strident]#

2.6) Deletion of [ā] before [ō] across a morpheme boundary (e.g. [laud-ā+ō] → laudō )

[ā] → Ø/__[ō]

Rule 2.1 accounts for the allophonic alternation of [ĕ] and [ĭ] in the paradigms of

conjugations III and IIIi by lowering [ĭ] before [ɾ]. Rule 2.2 accounts for the presence of a

vowel in the TV position of verbs from conjugation III, as well as for the lack of an [ĭ]

before the subjunctive marker -ā- when the surface forms of conjugations III and IIIi are

compared. The remaining allophonic alternations between long and short vowels are

accounted for by rule 2.3.

The synchronic productivity of Rule 2.1 is further exemplified if we turn to the

noun morphology of Classical Latin. One example in which the lowering of /ĭ/ in wordfinal position can be seen is in the third declension neuter noun rūs „country‟ which is a

normal third declension noun and mare „sea‟ which is a third declension ĭ-stem noun.

Inflectional form

nom./acc. sg.

nom. /acc. pl.

gen. pl.

Suffix

+Ø

+a

+um

„country‟

rūs

rūra

rūrum

„sea‟ ĭ-stem

mare

maria

marium

Table 2.6. Two third declension neuter nouns, from Redenbarger (1976: 2).

15

“The difference between the consonant final stem of rūs and the vowel final of mare is

clear, as is the alternation of [ĕ] / [ĭ] in that stem: [ĕ] appears word finally and [ĭ] before

vowels (Redenbarger 1976: 2).” The productivity of Rule 2.2 in the noun system is

revealed if we observe the dative / ablative plural forms of normal and ĭ-stem nouns of

the third declension.

Inflectional form

Suffix

„king‟

„sea‟ ĭ-stem

dat./abl. pl.

dat. / abl. pl.

+bus

*+ibus

regibus

regibus

maribus

*mariibus → marībus

Table 2.7. /ĭ/-epenthesis in third declension nouns.

If we take the suffix for the dative / ablative plural forms to be +ibus, given that mare is

an ĭ-stem noun, we would expect an ĭ+ĭ sequence (which Redenbarger shows to

“collapse” into a long ī by rule (1976: 3)). Instead we find the short vowel [ĭ] in both

regibus and maribus. This can be accounted for if we assume the suffix to be +bus. The

sequence [maɾĭ+bus] comes out cleanly as maribus. The /ĭ/-epenthesis rule can then take

care of the vowel that comes between the stem and suffix in the sequence [ɾeg+bus],

giving regibus.

Further evidence for the productivity of rule 2.1 can be found in the morphology

of words like corpus. This is shown in Table 2.8 where [ŭ] in the stem alternates with [ŏ]

in all forms where [ŭ] would have preceeded an [ɾ] (Redenbarger 1976: 6).

16

Rules

nom. / acc. singular dative singular

nom. / acc. plural

[kŏɾpŭs+Ø]

[kŏɾpŭs+ī]

[kŏɾpŭs+ă]

Rhotacism of /s/

[kŏɾpŭɾ+ī]

[kŏɾpŭɾ+ă]

Vowel-lowering

[kŏɾpŏɾī]

[kŏɾpŏɾă]

corporī

corpora

corpus

Table 2.8. Application of CL rhotacism and vowel-lowering in the inflection of corpus.

Rules 2.1-2.6 and the forms given in tables 2.3-2.8 are just a sample of how a

synchronic rule system that constructs the forms of the paradigm from abstract

underlying representations removes much of the mystery behind apparent irregularities

like the partial, but incomplete, similarity between the paradigms of CL conjugation-III

and conjugation-IIIi verbs, and between the paradigms of third-declension and thirddeclension ĭ-stem nouns.

Cases that remain apparently problematic like DARE, ESSE and FERRE (and

their related compounds) can also be accounted for. ESSE and FERRE belong to a

subgroup of the athematic conjugation. These verbs show irregularities in the perfect

system, a fact which suggests that these frequently-used verbs have maintained some

special morphological marking from a previous stage of Indo-European. Another feature

of this archaism is their morphological marking as non-epethesizing verbs, meaning that

they alone are exempt from the application of the /ĭ/-epenthesis rule. DARE is also an

athematic verb, but the apparent anomalies in its surface paradigm are not due to any

special marking as a non-epenthesizing verb. If we consider the internal structure to be

[da-Ø+re], where the root is vowel-final, we can see that the C__+C environment in

17

which /ĭ/-epenthesis occurs in other regular athematic verbs is absent. DARE is therefore

a regular Ø-theme verb whose root happens to end in /ă/ (Redenbarger forthcoming).

Given a convincing generative analysis of the Latin conjugations, in light of

morpho-phonological rules that can be shown to act productively elsewhere in Latin

morpho-phonology, such as that presented above in which the conjugations are not four,

but actually five in number, a reanalysis of the development of the Hispano-Romance

three-conjugation system is strongly warranted. “It is a century-old methodological

maxim that before doing historical comparative reconstruction, one must first do internal

reconstruction. Thus, given this new analysis of the synchronic system of Latin, previous

analyses of how Latin developed into the Romance languages must now be reconsidered

(Redenbarger 1976: 12).” We will begin a reconsideration of just this type with an

examination of a representative set of frequently-used Latin verbs from conjugations IIIV (see Chapter 5), and categorized by their theme-vowels following the schema put forth

by Redenbarger. A number of studies involving the historical development of the Spanish

conjugations, and in particular the changes in conjugation which took place among some

verbs which originated in CL conjugations II-IV, have given great importance to the root(or stem-) vowels as it pertains to their conjugation class membership in Spanish. These

studies include Wilkinson (1971), Togeby (1972), Montgomery (1976, 1978 & 1979),

Malkiel (1984), Lloyd (1987), and Penny (2002). It is therefore justifiable for us to

consider the root-vowels of CL verbs as they relate to their categorization by themevowel.

18

An Examination of Representative CL Verbs from Conjugations II-IV

Of the 305 frequently-used simple Classical Latin verbs selected as a starting

point for this research, the numerical distribution among the /ē/-theme, Ø-theme, /ĭ/theme and /ī/-theme verbs was far from equal. The Ø-theme verbs lead, constituting more

than half of the verbs from conjugations II-IV. The /ĭ/-theme verbs form the smallest

group. Their numbers shy in comparison to those of the Ø-theme verbs, a fact which

(given the overall similarity between the paradigms) certainly contributed to their

traditional classification as a subgroup of conjugation III.

A look at the root-vowels included within each conjugation is also illustrative.

Not surprisingly (due to their overall numbers), the Ø-theme verbs have a great variety of

RVs. These include /ā/, /ă/, /ē/, /ĕ/, /ī/, /ĭ/, /ō/, /ŏ/, /ū/ and /ŭ/ along with the diphthongs

/aj/ and /aw/, an inventory which exhausts the entire set of vowels possible in Classical

Latin with the unique exclusion of the diphthong /oj/. The /ē/-theme verbs have members

with each of the RVs listed above for the Ø-theme verbs, but /ī/, /ō/, and /ū/ are

represented by just one verb each. None of the /ī/-theme verbs in the data contains an RV

of /ā/, and there is only one verb each for the RVs /aj/ and /ō/. The RV inventory of the

/ĭ/-theme verbs is quite restricted. There are zero verbs in this conjugation represented by

the RVs /aw/, /aj/, /ē/, /ī/, /ō/ or /ū/. Thus, it is safe to say that long vowels were

extremely uncommon, if not non-existent as RVs in the verbs of this conjugation class.

Furthermore, while [ĭ] commonly appears in the RV position of prefixed compounds of

the /ĭ/-theme verbs, it is absent from the inventory of underlying RVs. This restricts the

set of possible underlying RVs in this conjugation to just four: /ă/, /ĕ/, /ŏ/ and /ŭ/.

19

These data stand in contrast to a claim made originally by Togeby (1972) and

sustained by Montgomery regarding the complementarity of stem-vowels and themevowels in Spanish. “No verbs of the Spanish –er conjugation contain stem-vowels i or u.

In contrast, all verbs of the –ir class, excluding a-stems and oír, are marked by either i or

u in the stems of some or all of their forms. Thus, broadly speaking, mid-vowels

characterize both stem and ending of one paradigm, and close vowels those of the other

(Montgomery 1976: 281).” If we compare just the /ē/-theme and /ī/-theme verbs from

Classical Latin, we can see that in the former the mid vowels (/ē/, /ĕ/, /ō/, /ŏ/) constitute

about 43% of the total RVs, the high (or „close‟) vowels (/ī/, /ĭ/, /ū/, /ŭ/) constitute about

34% and those with an RV of either /ă/ or /ā/ make up approximately 24%. For the /ī/theme verbs, mid vowels make up around 56% of all RVs, high vowels make up 36% and

the „a-stems‟ constitute about 8% of the total RVs. The proportion of mid vowels to high

vowels in these two conjugations is very similar. If we include the other CL conjugations

we see that the Ø-theme verbs show a similar pattern: mid vowels – 44%, high vowels –

46% and a-stems – 18%. For the /ĭ/-stems: mid vowels – 21%, high vowels – 14% and athemes 64%. The claim regarding complementary stem-vowels put forth by Togeby for

Spanish, which is supported by the corpus of data compiled for the present study, must

clearly have arisen within the Vulgar Latin of Hispania, as the pattern he describes cannot

be observed in a large corpus of representative data from Classical Latin like the one

examined here.

Let us now continue to a discussion about the CL verbs from conjugations II-IV

which did not survive in Hispano-Romance. If we group together the CL verbs in the

corpus which do not have reflexes in the data from HR, several general observations can

20

be made. There are several groupings of CL verbs which lost a majority of their

members during the development of HR. The majority of the /ĭ/-theme verbs was lost,

especially those that were prefixed forms of iacĕre (e.g. adicĕre, interficĕre, prōicĕre).

Some of these did find their way into HR, but through an indirect route, as firstconjugation verbs, presumably formed on the basis of the participle form. Take for

example CL prōicĕre and inicĕre, whose past perfect participle forms are prōiectum and

iniectum respectively. These survive in modern HR as proyectar (Cast.), projetar (Port.)

and inyectar (Cast.) injetar (Port.). A similar process can be observed in Modern

Portuguese where the verbs frigir „to fry‟ and fritar „to fry‟ (from CL frīgere, frictum)

coexist and share a common participle form frito. See Chapter 3 for further discussion of

this type of change.

Most prefixed īre compounds were also lost (e.g. invenīre, custodīre, coīre). Of

these, invenīre has also been adopted as the first-conjugation inventar in Spanish and

Portuguese, presumably on the basis of the perfect participle inventum.

Few of the CL verbs without an attested perfect stem survived in HR. We may

infer that the lack of an attested perfect form alludes to relatively low text frequency for

many of these verbs, a situation which could easily contribute to their loss from the

lexicon. Nearly half of the Ø-theme verbs whose RV was either /ĕ/ or /ŭ/ were lost, a

fact which may just be coincidental since /ĕ/ is the most numerous of the RVs for this

conjugation by far and /ŭ/ is also fairly numerous.

In sum, a number of facts about the morpho-phonology of Classical Latin can be

ascertained from the above discussion. Some of these challenge traditional descriptions of

21

Latin structure, while others present a novel perspective for the study of the development

of the conjugations of Hispano-Romance.

A morpho-phonological analysis of synchronic processes in Classical Latin

reveals a system of five conjugations characterized by the theme vowels: /ā/, /ē/,

Ø, /ĭ/ and /ī/.

The surface pattern of conjugation III verbs is largely due to the insertion of an

epenthetic /ĭ/.

The athematic (Ø-theme) verbs were the most numerous among CL conjugations

II-IV.

High and mid root vowels were more or less equally distributed in each of the CL

conjugations, not showing the complementarity of root vowel and stem vowel that

can be observed in Castilian.

The underlying RVs of the /ĭ/-theme verbs were limited to just four: /ă/, /ĕ/, /ŏ/,

/ŭ/.

The large majority of /ĭ/-theme verbs was lost.

A number of CL verbs from conjugations II-IV that did not develop directly into

HR –er or –ir verbs, survived through an indirect path as –ar verbs built from

perfect past participles.

This description is intended to serve as a point of comparison for the following

discussion of the morpho-phonological changes that took place in the system during the

22

development of the Hispano-Romance languages. Chapter 3 introduces the theoretical

framework which shall serve as the basis for that discussion.

23

Chapter 3: Historical Morphology and Phonology in Generative Grammar

An approach to the study of language change, which has been advocated by

Kiparsky (1965), King (1969) and others, is to approach historical linguistics as the study

of successive generations of productive, synchronic grammars, each producing the

language output for the various historical phases of the language in question. A detailed

analysis of the allomorphic alternations that can be observed in the data of a previous

stage of a language can lead us to fascinating insights into the phonological and

morphological processes that were productive in a given stage of a language‟s history.

A grammar in generative linguistics is defined as “a set of rules which

characterizes all and only the sentences of the language that we as speakers are able to

produce and understand (Crain & Lillo-Martin 1999: 5)”. These rules guide the

arrangement of items in the dictionary-like lexicon of the speaker in such a way that they

define the set of utterances pertaining to that language, and thusly define the structure of

the language. Of course, “[a]n important feature of the structure of a sentence is how it is

pronounced – its sound structure. The pronunciation of a given word is also a

fundamental part of the structure of the word (Odden 2005: 2)”. The grammar must, then,

define all aspects of the structure of a given language, with rules to dictate what is and is

not possible at every level of structure. For a child who is learning her native tongue, how

do these rules get into her mind?

24

The child is presented with certain “primary linguistic data”, data which are, in

fact highly restricted and degraded in quality. On the basis of these data, he

constructs a grammar that defines his language and determines the phonetic and

semantic interpretation of an infinite number of sentences (Chomsky 1968: 331).

“[T]o learn a language is to master the rules of the mental grammar (Crain &

Lillo-Martin 1999: 5).” The child language learner must acquire a grammar sufficient for

effective communication in her speech community: those who provide her with primary

linguistic data (PLD) by speaking in her presence. If she is successful in doing so, the

language output generated by her acquired grammar will be identical or nearly-identical

in structure to that of the speakers who provided her with the PLD. Since we have plenty

of documentation to show that language does indeed change across generations, it is

evident that something is impeding the child from acquiring (in every case) a grammar

identical to that of the previous generation. As Kiparsky states, “Imperfect learning is

due to the fact that the child does not learn a grammar directly but must recreate it

himself on the basis of a necessarily limited and fragmentary experience with speech

(1965: 1-4).” Due to this so-called poverty of the stimulus, such imperfections seem to be

a highly likely consequence of the language-learning process. Nonetheless, since

children are generally successful in acquiring a grammar that allows them to

communicate fully and successfully in their speech communities, the changes that result

from their “imperfect learning” must generally be minimal enough that the language

25

defined by their grammar is nearly the same as that from which they glean their PLD. It is

the job of the historical linguist to hypothesize as to how such changes arise.

The traditional study of sound change in historical linguistics involved the

formulation of rules that described the changes that took place across time in a language.

An example adapted from Penny (2002: 71) describes a consonant change that took place

in Spanish between the Classical Latin stage and the Old Spanish stage.

3.1) The palatalization of CL intervocalic -LL- in the development of Old Spanish.

-LL- > /λ/

Rule 3.1 is demonstrable through the juxtaposition of Latin words with their cognate

Spanish forms (e.g. CABALLU > caballo „horse‟, GALLU > gallo „rooster‟ and

VALLĒS > valles „valley‟). The complaint that has been made by generative linguists

about this type of rule is that it does not represent speaker competence. Since the speaker

of Latin and the speaker of Old Spanish were not the same individual, such a rule does

not describe a relationship between elements of the same grammar. As King puts it, “We

have nothing to gain from comparing phoneme inventories at two different stages of a

given language and seeing what sound has changed into what other sound. Such a

comparison gives as little insight into linguistic change as a comparison of before-andafter pictures of an earthquake site gives into the nature of earthquakes (1969: 39).”

King‟s essay on the place of historical linguistics in generative grammar describes a

different approach to the practice of historical phonology. “A proper historical phonology

is the history of the grammars of a language, of the competences of successive

26

generations of speakers. The listing of rules converting the sounds of proto-IndoEuropean into those of West Germanic may be of interest as an exercise in ingenuity and

distinctive feature virtuosity, but historical linguistics it is not (1969: 104).”

Following King‟s argument, the question of the origin of the palatal lateral in Old

Spanish must be viewed not as the formulation of a transformation rule, but rather as a

question of language transmission. What was it about the surface forms of Hispanic

Vulgar Latin that led the child learner of Old Spanish to construct a grammar with a

palatal lateral in contrast to the /ll/ sequence of Latin?

For the child acquisition of phonological grammars, Reiss and Hale propose a

directness principle in which “the initial state of the grammar is such that surface forms

and underlying representations are (a) assumed to be identical to each other, and (b)

identical to the (child‟s) parse of the output of speakers of the target language (2003:

151).” Their claim implies that the child‟s grammar initially contains no phonological

rules or processes. In the case of the Old Spanish palatal lateral /λ/, this implies that in

order for the child learner to include a palatal lateral in her lexical entries for horse,

rooster and valley, the surface forms she was exposed to must have had palatal lateral

consonants. Even if the speaker of Hispanic Vulgar Latin had a rule in her grammar

palatalizing the /ll/ sequence, if all instances of underlying /ll/ in her speech were realized

as [λ], there would be no reason for the child language learner to construct /ll/ as the

underlying form, thus producing a change in the underlying structure of the lexical items

in question.

27

Phonological change can also lead to morphological change. Examples of this can

be seen in data from throughout the Romance languages.

1st

2nd

3rd

Singular

pierdo

pierdes

pierde

Plural

perdemos

perdéis

pierden

Table 3.1. The present indicative paradigm of the Modern Castilian verb perder „to lose‟.

The allomorphy illustrated in Table 3.1 is the result of a phonological change by which

CL short non-high vowels were diphthongized in an earlier stage of Castilian (see

Chapter 4). Since the verb stem is not stressed in the 1PL and 2PL forms, the diphthongs

do not appear in the corresponding surface forms. This situation results in the presence of

two different forms of the verb root: perd- and pierd-. A similar pattern can be found in

Old French for the verb amer „to love‟ (Anderson 1979: 30).

1st

2nd

3rd

Singular

aime

aimes

aime

Plural

amons

amez

aiment

Table 3.2. The present indicative paradigm of the Old French verb amer „to love‟.

Table 3.2 illustrates the verb root allomorphy am- ~ aim- corresponding, like in

Castilian, to the unstressed and stressed positioning of the stem respectively. Such

28

allomorphy has been considered a somewhat destructive result of phonological change,

pulling paradigms apart and upsetting the ideal one-to-one correspondence between shape

and meaning. Consider now the paradigm of the Modern French verb aimer „to love‟ in

Table 3.3.

1st

2nd

3rd

Singular

aime

aimes

aime

Plural

aimons

aimez

aiment

Table 3.3. The present indicative paradigm of the Modern French verb aimer „to love‟.

The verb root has the unique shape aim- in all forms of the paradigm. The change

observable through the comparison of Tables 3.2 and 3.3 is an example of what has been

called analogical leveling, and some linguists have considered it to be a response

phenomenon which undoes the destructive effect of phonological change on morphology

(Hock 2005: 450). We now turn to some examples of morphological change in Romance

which appear to have taken place in a similar fashion, but which do not result from

allomorphy that has directly arisen from phonological change.

In Hispano-Romance the past perfect (preterite) verb forms are generally

categorized as either strong or weak, depending on whether the word stress is on the stem

or the inflectional suffix respectively. The weak preterites are in the majority and verbs

of recent coinage, which all pertain to the /a/-theme conjugation, all show the weak

preterite pattern: e.g. Castilian fotocopiar „to photocopy‟, fotocopié „I photocopied‟. This

29

indicates that the rule forming weak preterites is synchronically productive, whereas the

strong preterites, which bear resemblance to cognate Classical Latin perfect forms, are

most likely marked in the lexicon as exceptional, and have separate lexical entries for

their preterite form.

Vicente cites some examples of innovative weak preterite forms characteristic of

the speech of Bielsa and Aragüés in the Aragonese language zone of Spain (1967: 258).

„I found out‟

„I said‟

„I had‟

Aragonese

sabié

dicié

tenié

Standard Castillian

supe

dije

tuve

Table 3.4. Innovative weak preterites in Aragonese and their standard Castilian

equivalents.

We might say that, through a comparison with the more numerous weak preterite forms,

Aragonese innovated weak preterite forms for these verbs. At some stage in the history

of Aragonese the child learners may have failed to incorporate the additional lexical entry

for the preterite forms of these verbs into their grammar. We cannot know for sure if the

necessary input for them to reconstruct the strong preterites was absent or infrequent in

their PLD, or if the loss of these forms is simply due to an overriding of the data as

suggested by Kiparsky (1965: 2-15). In any case, the change can be seen as a

generalization of the rule which forms preterites in the sense that fewer verbs must be

marked as exceptional and have dual lexical entries. Should the rule continue to

30

generalize, it is not difficult to imagine a total loss of the strong preterites in a future

stage of the language.

Finally, let us examine an example of ongoing morphological change in Modern

Portuguese. In Portuguese there are two synonymous verbs meaning „to fry‟, frigir (a

third-conjugation verb) and fritar (a first-conjugation verb). Both verbs share the past

(perfect) participle form frito, and both verbs are derived from the Classical Latin Øtheme (conjugation III) verb frīgĕre „to roast‟, whose past perfect participle is frictum.

Of the competing infinitive forms, frigir (based on the CL conjugation III infinitive)

seems to be loosing ground to fritar, which has every appearance of having been

constructed with a basis on the participle. To give a rough demonstration of this trend; a

search of Portuguese-language websites performed on Google.com on 02-23-2010

returned 31,400 hits for the keyword frigir as opposed to 349,000 hits for fritar. What

might be the cause behind this apparent preference for the –ar verb? As I previously

mentioned, in the modern HR languages, only the first conjugation in synchronically

productive, and new verbs coined in the language are adapted to the morphology of this

particular class of verbs (see Chapter 6 for further discussion). If we assume,

hypothetically, that a child learner of Portuguese is exposed more frequently to the

participle forms of this verb (masc. sing. frito, fem. sing. frita, masc. pl. fritos, fem. pl.

fritas) than to the infinitive or another inflected form of the verb, then it is absolutely

unsurprising that she would posit fritar, with an underlying structure like [fɾit-a+ɾ] where

the root frit- is the common element in all of the participle forms, -a- is the theme-vowel

of the (synchronically-productive) first conjugation, and –r is the infinitive marker. Of

course, with sufficient input and reinforcement, she may or may not later replace this

31

form with the competing frigir [fɾiʒ-i+ɾ], whose root shape is somewhat more similar to

that of the CL frīgere [fɾīg-Ø+ɾe]. This relationship between frequency and

morphological change has often been observed. Krazka-Szlenk affirms that,

“[a]llomorphy positively correlates with high text frequency, while rare text frequency

favors stem leveling. Anything else being equal, it is the more frequent allomorph (in

terms of text frequency) which becomes the Base for leveling, and not a rarer one (2007:

198)”.

We have seen a variety of changes in the phonology and morphology of several

Romance languages in the examples above. These changes have demonstrated how a

phonologically-conditioned change can lead to allomorphy, and how allomorphy can

serve as the basis for leveling by analogy. We have also discussed in this chapter how the

transmission of language from the community of speakers to the child learner can lead to

the generalization or loss of grammatical rules, and the reinterpretation of underlying

structure, between one stage of the language and another. Of course, such changes do not

happen suddenly and categorically between one generation and the next, as such

examples may persuade us to believe. It is quite possible that most innovations begin

initially as added optional rules that subsequently become obligatory (King 1969: 99).

Such a statement is supported by the variation that can be observed in all natural

languages, including those which are no longer spoken, and the presence of variation

should always be taken into consideration in the analysis of any corpus of linguistic data

be it historical or contemporary. In Chapter 4 I will review some of the major morphophonological developments which occurred in the Vulgar Latin of Hispania. These

32

changes set the stage for the divergence of the various Hispanic languages and for the

development of their three-conjugation system of verbal morphology which is the focus

of the present study.

33

Chapter 4: Relevant Phonological Changes in the Vulgar Latin of the Iberian Peninsula

In order to reconstruct the various stages in the evolution of the HispanoRomance conjugation classes it is necessary to understand the relevant synchronicallyproductive rules that were at work in the various stages of the language between Classical

Latin and Modern Castilian and Portuguese. In this chapter I will outline the major

morpho-phonological developments in Hispano-Romance, as relevant to the changes that

took place in the conjugational system.

The Development of the Vowel System

The vowel system of Classical Latin (see Chapter 2) underwent several major

changes en route to developing into the vowel systems of Hispano-Romance. The claim

has been made many Romance scholars, including Penny (2002: 45), that the short

vowels, with the exception of /ă/ which is not considered tense to begin with, became [atr] („atr‟ stands for the distinctive feature „advanced tongue root‟. See Redenbarger

1981.), or lax. Clearly, such a process of laxing must have occurred before the loss of

quantitative distinction in order to apply only to those vowels which had once been short,

and would have resulted in a vowel inventory like that given in Fig. 4.1, where the

difference between the long and short vowels is accompanied by an articulatory

difference; that of [±atr] or tense ~ lax.

34

ī

ū

ɪ

ʊ

ē

ō

ɛ

ɔ

ă, ā

Figure 4.1. The Vulgar Latin vowel inventory as described by many traditional accounts.

One major problem with this traditional analysis is that the high lax vowels [ɪ] and

[ʊ] are unattested in the Romance languages. However, the lax vowels [ɛ] and [ɔ] are

attested in all major branches of Romance. Thus, based on attested Romance vowel

systems, we can assume for Vulgar Latin a synchronic rule (4.1) by means of which the

underlyingly short non-high vowels /ĕ/ and /ŏ/ were laxed in stressed position.

4.1) Early Vulgar Latin laxing rule for /ĕ/ and /ĕ/.

V[+stress –long –high –rtr] → [-atr]

At approximately the same stage we can also assume a productive rule (4.2) lowering the

underlyingly short high vowels /ĭ/ and /ŭ/ to [ĕ] and [ŏ] respectively.

4.2) Early Vulgar Latin vowel lowering rule.

V[-long] → [-high]

35

We can hereby present a more plausible set of surface vowels for this early stage of the

Vulgar Latin of Hispania. Figure 4.2 illustrates the output of the CL vowel inventory after

the application of rules 4.1 and 4.2

ī

ū

ĕ

ŏ

ē

ō

ɛ

ɔ

ă, ā

Figure 4.2. The Vulgar Latin surface vowels before the loss of the length distinction.

By the first century AD, Vulgar (spoken) Latin had lost the meaningful phonemic

distinction between long and short vowels that characterized the vocalic system of

Classical Latin (Penny 2002: 45). It is unknown exactly why the length distinction was

lost, but the tense ~ lax distinction clearly grew to be more prominent in the

differentiation between words. As vowel length ceased to be essential for effective

communication, the child learners ceased to encode it into their grammars, and so, per

Reiss and Hale‟s directness principle, we can construct the inventory of vocalic

phonemes in VL that must have preceded the vowel inventories of all Hispano-Romance

varieties.

36

i

u

e

o

ɛ

ɔ

a

Figure 4.3. The Vulgar Latin inventory of vocalic phonemes after the loss of the length

distinction.

Word stress also came to play an important role in the vowel system of HispanoRomance. This may be due in part to the change in accent type that occurred during the

development of Vulgar Latin. It is believed that Latin accent was of the pitch type,

whereas Hispano-Romance accent is of the stress type (Penny 2002: 42).

The increasingly uneven deployment of energy over the word (more to the tonic,

less to the atonics) accounts in large part for the differential historical treatment of

the Latin vowels in different positions. Concentration of energy on the tonic (and

the greater audibility this brings) allows vowels to be quite well differentiated and

preserved, while lesser degrees of energy devoted, in decreasing order, to initial,

and final and intertonic vowels imply greater degrees of merger and loss (Penny

2002: 43).

We can see from the data available to us that stressed, or tonic, vowels in

Hispano-Romance have developed differently from the unstressed, or atonic, vowels.

The inventory of vowels which appear in atonic position is restricted in comparison to

37

that of vowels which occur in tonic position. This change in itself is a significant

departure from the CL system in which any vowel, long or short, could occur in either

stressed or unstressed position in a word.

CL tonic vowels

ā

ă

ē

ĕ

>

>

>

>

ī

ĭ

ō

ŏ

>

>

>

>

ū

ŭ

>

>

HR tonic vowels

a

a

e

ɛ

i

e

o

ɔ

u

o

Table 4.1. The tonic HR outcomes of CL vowels.

CL atonic vowels

ā

ă

ē

ĕ

ī

ĭ

ō

ŏ

ū

ŭ

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

HR atonic vowels

a

a

e

e

i

e

o

o

u

o

Table 4.2. The atonic HR outcomes of CL vowels.

38

An examination of Tables 4.1 and 4.2 above reveals that in both the tonic and

atonic vowels of Hispano-Romance, several of the vowels that were distinct from one

another have merged. In fact, if we study the atonic vowels of Hispano-Romance which

appear in word-final position, it becomes evident that these merged even further,

resulting in a mere three-way distinction. The results of these mergers are summarized in

tables 4.3 – 4.5.

CL Vowels

ā

HR tonic

vowels

ă

ē

a

ĭ

ĕ

ō

ɛ

e

ŭ

o

ŏ

ī

ū

ɔ

i

u

ŏ

ī

ū

i

u

Table 4.3. The merger of CL vowels in HR tonic position.

CL Vowels

HR atonic

vowels

ā

ă

a

ē

ĭ

ĕ

ō

e

ŭ

o

Table 4.4. The merger of CL vowels in HR atonic position.

39

CL Vowels

Word-final

HR atonic

vowels

ā

ă

a

ē

ĕ

ī

ĭ

ō

e

ŏ

ū

ŭ

o

Table 4.5. The merger of CL vowels in HR word-final atonic position.

The Classical Latin diphthongs [aj], [oj] and [aw] also underwent changes. In

Vulgar Latin, [aj] became [ɛ] and [oj] became [o]. There is also evidence that [aw]

sometimes became [o] during the same stage (such as the coexistence of forms like

CLAUDIUS and CLODIUS), but it was not until much later that this change was

generalized via a stage as [ow], which still persists in Portuguese (Elcock 1960: 43).

The vowel inventories illustrated in Tables 4.3 – 4.5 are relatively well preserved

in modern HR varieties, like Portuguese and Galician, which maintain a phonemic

distinction between seven oral vowels. However, further east on the Iberian Peninsula,

varieties like Leonese, Asturian, Castilian and Aragonese have subsequently lost the

tense ~ lax distinction (between [e], [o] and [ɛ], [ɔ] respectively). This occurred through a

process of diphthongization, in which the lax vowels came to be realized as diphthongs

(see Garcia de Diego 1909, Menéndez Pidal 1962, and Alvar 1953). Although the exact

contexts in which this occurred vary from language to language, the change can be well

40

illustrated by the one that took place in Castilian whereby /ɛ/ > /je/ and /ɔ/ > /we/ (Penny

2002: 52).

Changes in Accentuation

“[T]he position of the [Classical] Latin accent was determined by the

phonological structure of the word concerned and never by its meaning (Penny 2002:

41).” The rule of accentuation in CL was based on syllable weight, whereby a long

syllable is considered heavy and a short syllable is considered light. Syllable length and

accent position are determined by the following rules. In multi-syllabic CL words, either

the penultimate or antepenultimate syllable will bear the accent. In words of two

syllables, the penultimate syllable is accented. In words of more than two syllables, the

penultimate syllable receives the accent if it is long. If the penultimate syllable is short,

the antepenultimate syllable will bear the accent of the word. An open syllable ((C)V

structure) is long if it contains either a long vowel or a diphthong. Closed syllables

((C)VC structure) are also considered long. An open syllable containing a short, simple

vowel is a short syllable (Moreland & Fleischer 1977: 3). Therefore, a CL verb form like

FĂCĔRE (with a short penultimate syllable) would be stressed on the antepenultimate

syllable, whereas a verb form like DĒBĒRE (with a long penultimate syllable) would

bear penultimate stress.

For the most part, the Hispano-Romance languages maintain the stress on the

same syllable which was stressed in CL, even though the overall number of syllables, or

position of the stressed syllable relative to the number of syllables in the word, have

changed in many cases. Consider two examples from Castilian: MĀTERĬA > madera,

and DĒBĒRE > deber. MĀTERĬA was a four-syllable word with antepenultimate stress

41

[mā.‟tĕ.ɾĭ.ă]. Even though madera [ma.‟ðe.ɾa] is a three-syllable word in Castilian, we

can clearly see that the stressed is maintained on the same vowel which bore it in Latin.

DĒBĒRE was a three-syllable word with penultimate stress [dē.‟bē.ɾĕ]. The final vowel

was lost in Castilian, and yet the stress persists on the same vowel, despite its position in

the final syllable of the word [ðe.‟βeɾ].

Hispano-Romance, in contrast with the other Romance families, extended this

accentuation pattern on verb infinitives to all verbs, including those which bore word

stress on the antepenultimate syllable in CL (like FĂCĔRE) (Penny 2002: 154). As I will

show in Chapter 6, this generalization of the stress pattern of infinitives contributed to the

reduction of the conjugation classes to three in HR. Since the regularization of the stress

pattern of verb infinitives in all conjugations is unique, within Romance, to the Hispanic

languages, it is reasonable to assume that this development occurred in the late stages of

Vulgar Latin within that geographical area.

The overall retention of word-stress position, in spite of the changing shape of

Hispano-Romance words, ultimately led word stress to have distinctive, phonemic value,

since stress placement was no longer entirely predictable by phonology alone.

Loss of Intertonic Vowels

The internal (neither word-initial nor word-final) unstressed vowels of CL are

often referred to as intertonic vowels. These were often lost entirely in Vulgar Latin as

evidenced by inscriptions in the Appendix Probi. For example:

42

ANGULUS NON ANGLUS

CALIDA NON CALDA

SPECULUM NON SPECLUM

STABILUM NON STABLUM

VETULUS NON VECLUS

VIRIDIS NON VIRDIS

With the exception of /a/, Latin intertonic vowels have been almost entirely

eliminated in orally-transmitted words throughout the Romance languages (Penny 2002:

59). The fact that intertonic vowels were lost is often key in determining which words

have been borrowed back into Romance from Latin, as opposed to having passed through

all the stages of development that occurred as part of oral transmission. See Chapter 6 for

further discussion of this topic.

Rule Changes

As we have seen in the preceding chapter, phonologically-conditioned changes in

language can lead to the alteration, addition or loss of synchronically-productive rules in

the grammar of subsequent generations of speakers. Several such rule changes in

Hispano-Romance are relevant to the development of the verb conjugations.

Due to the allomorphic alternations observable in the inflectional paradigms of

words which contain lax vowels in some of their surface forms, the child learner of

Vulgar Latin would need to construct an unstressed tensing rule (4.3) to account for the

surface distribution of the lax vowels, and their appearance in stressed syllables only.

43

4.3) Vulgar Latin unstressed tensing rule

V[-stress] → [+atr]

The rule which deleted the TV -ā- before the 1SG marker –ō in first-conjugation

CL verbs like CANTŌ [kant-ā+ō] (Rule 2.6) became generalized in Vulgar Latin to the

extent that all TVs were deleted across a morpheme boundary when to the left of another

vowel. Therefore, CL verb forms like the first person singular indicative active DĒBEŌ

[deb-ē+ō] and first person singular subjunctive active DĒBEĀ [deb-ē+ā+Ø], in which the

TV /ē/ is apparent in the surface form, came to be realized without the TV in the surface

form just like their contemporary reflexes in Portuguese (devo and deva), and Castilian

(debo and deba).

The loss of word-final nasal consonants in Latin occurred by the first century A.

D. with the exception of a few frequent monosyllabic words in which the final nasal

consonants were preserved (e.g. QUEM, TAM, CUM). By the time we reach the earliest

stages of Old Castilian and Old Portuguese, around the 12th century AD, the word-final

stop consonants had probably fallen out of the underlying lexical representations of HR

speakers due to their absence in the surface forms of the PLD. The possible exception to

this is the third-person singular marker, which has been attested inconsistently in

manuscripts as both –t and –d up through the early thirteenth century (Lloyd 1987: 281),

although its appearance in written texts is feasibly due to the dual literacy in both

Classical Latin and Romance of the early Romance authors. It is reasonable to suggest,

44

then, that a socially-variable rule like Rule 4.4 that deleted final stop consonants was

present in Vulgar Latin until its latest stages.

4.4) Variable deletion of word-final stop consonants in Vulgar Latin

C[-cont] → Ø/__#

The above-mentioned changes in the morpho-phonology of the Vulgar-Latin of

Hispania led to an increasing similarity among the verbs which were developing from

those of CL conjugations I-IV. The combined effects of these changes in the vowel

inventory and grammar of the language would lead us to expect a change in the

conjugation classes of HR like that illustrated below in Table 4.6.

Latin Conjugation I

Latin Theme Vowel [ā]

II

[ē]

IIIa

Ø

HR Conjugation

HR Theme Vowel

[e]

[e]

I

[a]

IIIb

[ĭ]

IV

[ī]

[e]

III

[i]

II

Table 4.6. The predicted reclassification of the CL verb conjugations in HR based on

regular sound change.

As we can clearly see when we examine the reflexes of these verbs in Modern

Castilian and Portuguese, the changes in conjugation class were not entirely as regular as

our study of these major structural changes in the Vulgar Latin of Hispania would lead us

to predict.

45

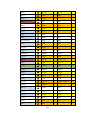

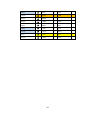

Chapter 5: Historical Data from Hispano-Romance

In order to collect and organize a large amount of verb data from Classical Latin

and the Hispanic daughter languages, a spreadsheet was created in Microsoft Excel 2007.

The software was chosen because it allows data to be organized in columns and rows

which can be sorted alphabetically, numerically or by cell color for an added dimension.

Selected columns or rows can also be hidden at the user‟s discretion. These features

prove extremely useful to the visually-oriented researcher who is looking for patterns

within the data. First, a column was created for Latin verbs, to be listed by their present

active infinitive form. Given that the focus of the present study is the historical linguistic

development of the /e/-theme (second) and /i/-theme (third) conjugation classes of the

Hispano-Romance languages from the Classical Latin conjugations II-IV, it was

necessary to collect a representative sample of Hispano-Romance verbs that derived from

Latin verbs in those classes. To do so, it was convenient to begin with a listing of

commonly used Latin Verbs under the assumption that words employed with higher

frequency have a greater chance of surviving in the lexicon of subsequent generations of

speakers. For this I turned to the book 501 Latin Verbs fully conjugated in all the tenses

in a new easy-to-learn format alphabetically arranged (501 Latin Verbs) (Prior &

Wohlberg 1995), and to Joseph Wohlberg‟s original 201 Latin Verbs Fully Conjugated in

all the Tenses Alphabetically arranged (201 Latin Verbs) (1964). In 201 Latin Verbs,

46

Wohlberg chose his verbs from the New York State Regents examinations and various

College Board tests. Prior expanded upon this work in 501 Latin Verbs by including the

“highest-frequency verbs in Classical Latin and all the irregular and defective verbs”

(Prior 1995: vii). I began collecting data by selecting the verbs from the main entries of