* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

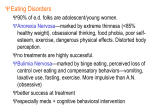

Download Conceptualization of anorexia nervosa : a theoretical synthesis of

Psychological evaluation wikipedia , lookup

Conversion disorder wikipedia , lookup

Separation anxiety disorder wikipedia , lookup

Pyotr Gannushkin wikipedia , lookup

Classification of mental disorders wikipedia , lookup

Generalized anxiety disorder wikipedia , lookup

Asperger syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Glossary of psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders wikipedia , lookup

Controversy surrounding psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Narcissistic personality disorder wikipedia , lookup

History of psychiatric institutions wikipedia , lookup

Dissociative identity disorder wikipedia , lookup

Control mastery theory wikipedia , lookup

Moral treatment wikipedia , lookup

Bulimia nervosa wikipedia , lookup

History of psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Mental status examination wikipedia , lookup

History of mental disorders wikipedia , lookup

Emergency psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Child psychopathology wikipedia , lookup