* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Solidifying Federalism by Recognizing Secession As a Legitimate

Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution wikipedia , lookup

Union (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

United States presidential election, 1860 wikipedia , lookup

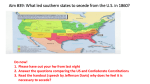

Alabama in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Texas in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Virginia in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Mississippi in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Tennessee in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Baltimore riot of 1861 wikipedia , lookup

Georgia in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Border states (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Missouri secession wikipedia , lookup

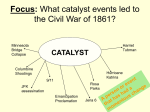

Issues of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup