* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 00 Inizio PACE - Plants and culture: seeds of the cultural heritage of

Evolutionary history of plants wikipedia , lookup

Plant stress measurement wikipedia , lookup

History of herbalism wikipedia , lookup

Plant nutrition wikipedia , lookup

Venus flytrap wikipedia , lookup

Plant use of endophytic fungi in defense wikipedia , lookup

Plant secondary metabolism wikipedia , lookup

History of botany wikipedia , lookup

Flowering plant wikipedia , lookup

Plant defense against herbivory wikipedia , lookup

Ornamental bulbous plant wikipedia , lookup

Plant breeding wikipedia , lookup

Plant physiology wikipedia , lookup

Plant evolutionary developmental biology wikipedia , lookup

Plant morphology wikipedia , lookup

Plant reproduction wikipedia , lookup

Flora of the Indian epic period wikipedia , lookup

Verbascum thapsus wikipedia , lookup

Sustainable landscaping wikipedia , lookup

Plant ecology wikipedia , lookup

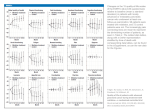

Bracken (Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn), mistletoe (Viscum album (L.)) and bladder-nut (Staphylea pinnata (L.)) - mysterious plants with unusual applications. Cultural and ethnobotanical studies Jacek MADEJA1, Krystyna HARMATA1, Piotr KOŁACZEK 1, Monika KARPIŃSKA-KOŁACZEK 1, Krzysztof PIĄTEK 2 and Przemysław NAKS 3 1 Department of Palaeobotany, Institute of Botany, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland Department of Plant Ecology, Institute of Botany, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland 3 Department of Plant Taxonomy and Phytogeography, Institute of Botany, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland 2 Abstract Rośliny od niepamiętnych czasów nie tylko pomagały zaspokoić głód i uzupełnić dietę. Na przestrzeni wieków człowiek zdobył i przekazywał wiedzę o ich właściwościach leczniczych, czy trujących. Ale ten bezpośredni kontakt z roślinami miał też inny wymiar, nie tylko materialny, ale i duchowy związany z wierzeniami w niezwykłą moc niektórych roślin. Rośliny miały swoje miejsce w sztukach magicznych, w zwyczajach, albo w ustalonych formach religii. Tu przyglądniemy się trzem wybranym przez nas gatunkom na różnych płaszczyznach związanych z człowiekiem. Kłącza Pteridium aquilinum w ciężkim dla człowieka czasie ograniczonego dostępu do pożywienia były wykorzystywane do celów konsumpcyjnych. Z nasion Staphylea pinnata sporządzano biżuterię oraz różańce, natomiast Viscum traktowana była jako roślina magiczna, a także lecznicza. Plants for ages have helped in satisfying hunger and supplementing a diet. For centuries man has gained and handed on knowledge about their properties, both curative and poisonous. However, this close relationship with plants had also different meaning, not only a physical one, but also spiritual that was connected with beliefs in extraordinary power of some plants. Plants had their place in magical arts, customs or certain forms of religion. Here we take a closer look at three chosen species in different areas connected with humans. Bracken rhizomes, during difficult times of limited food availability, were used for culinary purposes. Seeds of bladder-nut were popular in adornments and rosaries, this shrub was also considered to have magical power. Mistletoe established its reputation as a cult plant, moreover it was and still is in use in medicine. 1. - Distribution of bracken (Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn) in Poland (Zając and Zając 2001). Pteridium Pteridum aquilinum is a cosmopolitan species with an almost worldwide distribution apart from mountainous, desert and arctic areas. P. aquilinum subsp. aquilinum occurs mainly in the northern hemisphere, whereas P. aquilinum subsp. caudatum dominates in the southern hemisphere (Thomson 2000; Thomson and Alonso-Amelot 2002). Pteridium reproduces mainly vegetatively. Its rhizomes are located deep underground so that they are protected both against frost and fire. On burnt areas Pteridium produces leaves very quickly, blocking the light available to other competitors (Stickney 1986; Taylor 1986). Additionally, it has the ability to release allelopathic phytotoxins to prevent or moderate other plant growth in the nearest vicinity (Brown 1986). The present distribution of Pteridium aquilinum in Poland is presented on fig. 1 (Zając and Zając 2001). Because acid substratum facilitates the germination of spores (Page 1986), in fire-prone areas, especially in 207 P l a n t s a n d C u l t u r e : s e e d s o f t h e c u l t u r a l h e r i t a g e o f E u r o p e - © 2 0 0 9 · E d i p u g l i a s . r. l . - w w w. e d i p u g l i a . i t MYSTERIOUS PLANTS WITH UNUSUAL APPLICATIONS. CULTURAL AND ETHNOBOTANICAL STUDIES 2. - Spore of bracken (Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn). places where forest fires occur, the occurrence of a large number of young Pteridium specimens has been observed (Oberdorfer 1990), contributing to a decrease in substratum pH. Pteridium aquilinum is a pioneer plant which does not tolerate shading. It occurs in disturbed localities (Jackson 1981), in forest clearings and forest edges. It frequently occupies moors, drying swamps and appears in fields under cultivation. In Poland, Pteridium aquilinum spores have been recorded since the end of the Vistulian (fig. 2). Their greatest abundance in pollen spectra is noticeable between 8000-5000 BP, during which Pteridium constituted an important element of pine and mixed deciduous forests (Madeja et al. 2004). Undoubtedly, the frequent occurrence of Pteridium aquilinum at this time was connected with forest clearing by Mesolithic and Neolithic human groups. The Polish name “orlica” refers to the vascular bundle arrangement in the stipe which on cross-sections is reminiscent of a flying, double eagle. Pteridium aquilinum is one of the many members of the plant world that have practical and diverse uses. Despite its worldwide distribution, the range of basic applications is very similar across its range and is connected mainly with use as a food source. In Europe, western bracken rhizomes were consumed most likely even in the Middle Stone Age (Göransson 1986). Its poisonous qualities have been known for a long time. Ptaquiloside - the main toxin of bracken - causes frequent intoxications and even leads to death of domestic animals, while thiaminase, another active agent, causes disturbance in the absorption of vitamin B1 (Fenwick 2006, Yamada et al. 2007). In Japan and Korea, where bracken is an important dietary element, an archaic method of disposing of the toxic substances from young plant parts is used even today. This method consists of soaking bracken in water for a day with the addition of ash, and boiling afterwards; young plants can then be consumed as a vegetable or as a soup (called “warabe”) (Pieroni 2005). A similar way of discarding the toxic residues and bitter taste is given in the guidebook entitled: Dzikie rośliny jadalne Polski. Przewodnik survivalowy (Wild edible Polish plants. Survival Guidebook, in Polish) (Łuczaj 2004). Because bracken’s rhizomes contain up to 60% starch, they were often dried and used as a valuable starch source. Unfortunately, they have a bitter, unpleasant taste that is hard to get rid of. One way of eliminating the taste involves drying (in this state they can be stored for years), removing the black peel and threshing with the use of a stick, causing the disintegration of the dry farinaceous parts from among the hard, oblong fibers (Łuczaj 2004). Rhizomes grinding yielded similar results. Flour obtained in this way was commonly added to bread baking, especially during periods of famine. In France this kind of bread was baked during the Great Famine (Coquillat 1950). The oldest written information related to using ferns as a source of food in Great Britain reads as follows: «Poor people made the bread of fern roots» (Caxton 1480). During the First World War, which significantly limited food availability for people as well as for animals, greater attention was paid to the possibility of using rhizomes of bracken as food. Such observations were initiated in Scotland and conducted also in other countries (Hendrick 1919). Recipes for boiled bracken leaves appeared in British newspapers at that time (Braid 1934). Suggestions included using green, still twisted leaves as an asparagus substitute and also the possibility of using young rhizomes for brewing. Both bracken rhizomes and leaves were used as fodder for domestic animals. In Wales, shredded dried leaves mixed with straw or hay were given to horses and mules pulling trams during winter. Leaves were also given to rabbits. Because of its chemical properties, bracken was used in folk medicine for a long time. Dried, powdered rhizomes were utilized most often. Powder was added to wine or water sweetened with honey. A drug prepared in this way was known for its anti-ascaris and antiparasitic properties. There is also a known analgesic property of the aqueous extract made from bracken rhizomes (Pieroni and Quave 2005); in Poland there is a conviction that compresses made of dried bracken leaves bring relief from rheumatic pain (personal information). Pteridium was also used as an abortive agent in domestic animals (Viegi et al. 2003). 208 P l a n t s a n d C u l t u r e : s e e d s o f t h e c u l t u r a l h e r i t a g e o f E u r o p e - © 2 0 0 9 · E d i p u g l i a s . r. l . - w w w. e d i p u g l i a . i t J. MADEJA, K. HARMATA, P. KOŁACZEK, M. KARPIŃSKA-KOŁACZEK, K. PIĄTEK, P. NAKS The charcoal (cinder), result of the burning of bracken leaves, mixed with a small amount of olive oil, was also used to treat bite wounds caused by wolves (Guarrera et al. 2005). Apart from the common use as a source of food and medicinal substances, Pteridium also had a whole spectrum of other practical, and sometimes amazing uses. Because of the high potassium content in ash, after lixiviation bracken was a frequent additive in glass production during the Middle Ages (Jackson and Smedley 2008). Ash from bracken was also used as a cheap washing detergent for clothes. Ash balls were often bought as a universal washing agent (Morris 1947). After mixing ash with oil and suet, more expensive washing detergents, soaps, were made. As a highly energetic plant, bracken was used as fuel from which briquettes burned in stoves were made (Callaghan et al. 1981). Bracken leaves were used to thatch roofs and also as bedding for cattle. They were also processed for compost (Pitman and Webber 1998). In the Mediterranean area bracken leaves are frequently used by shepherds to filtrate sheep milk and for freshly made ricotta cheese preservation (Pieroni 2005). The germicidal and fungicidal substances contained in bracken leaves make food wrapped in them resistant from perishing. Some gardeners in Poland who avoid available commercial chemical plant protection products use an aqueous extract from bracken leaves for spraying plants in order to control plant lice or for watering plants as an anti-snail agent (personal information). Human activity contributed to an increase in the area occupied by bracken at least since the Middle Stone Age. Observations from Finland (Oinonen 1976) show a correlation between an increase of new areas occupied by bracken and periods when warfare took place. Warfare induced frequent forest fires that promoted the spread of bracken. Today, the continuing expansion of Pteridium species is troublesome and hard to control in Europe and globally (Cox et al. 2007; Pakeman et al. 2005; Hartig and Beck 2003). Human intervention made it possible for bracken to spread to new areas, made use of the plant through various applications, and frequently helped bracken survive hard times. Now man is trying to find a way to stop the expansion of bracken. Viscum Viscum is an amazing plant that lives at the expense of its hosts which constitute various tree species. In autumn and winter, when trees stand leafless, green spheres of various size, formed by the twigs of Viscum, can be seen from afar. Underneath the bark of the host 3. - Pollen grain of mistletoe (Viscum album (L.)). tree, mistletoe forms a branched system of suckers used to absorb water and mineral salts. Because of its evergreen, olive-green coloured leaves and twigs that seem to be dychotomically branched, Viscum can assimilate self-sufficiently. Mistletoe’s shoots divide into nodes and internodes. A new dichotomy appears every year, so by counting these it is possible to determine the age of the plant. Individuals can live for 30-40 years (Stypiński 1997). There is considerable variation in Viscum in the selection of tree species as hosts, particular subspecies demonstrate important differences in this regard. Viscum occurs on trees that are 20 years old at least. It also shows preferences for trees that grow in soils rich in calcium carbonate. Mistletoe is dioecious and is usually in bloom from February till April. Male flowers are characterized by a single yellow-green perianth with four sepals that join at the base and form a short tube. Instead of typically formed stamens, at the base of the perianth occur up to 50 anthers that burst and enable the spread of pollen. These flowers also produce a large amount of nectar. Female flowers usually occur in trios surrounded by a small inconspicuous perianth, they also produce nectar but, in contrast to male flowers, they possess very little detectable odour. Flowers are probably pollinated by insects among which bees probably play an important role. Nevertheless some researchers claim that this plant is also wind-pollinated. Mistletoe is a sparse pollen producer (fig. 3) (Stypiński 1997). Berries grow on female specimens after spring pollination. These mature in late autumn or winter and can be distributed by birds, mostly by waxwings and mistle thrushes, which swallow whole fruits and enable long distance dispersal. Other birds nibble fruits which can easily attach to the branches 209 P l a n t s a n d C u l t u r e : s e e d s o f t h e c u l t u r a l h e r i t a g e o f E u r o p e - © 2 0 0 9 · E d i p u g l i a s . r. l . - w w w. e d i p u g l i a . i t MYSTERIOUS PLANTS WITH UNUSUAL APPLICATIONS. CULTURAL AND ETHNOBOTANICAL STUDIES 4. - Distribution of mistletoe (Viscum album (L.)) in Poland (Zając and Zając 2001). of the host-tree due to their sticky flesh, afterwards they form suckers and eventually roots. Mistletoe is a phytoindicator of environmental contamination with heavy metals (Stypiński 1981, 1997). However, the branches of trees on which it parasitizes are deprived of water and mineral substance inflow which can lead to desiccation. If there are many specimens on one tree, Viscum may cause the death of the host. Fossil remains of the genus Viscum were identified in the younger periods of the Neogene. They were accompanied by tree genera including maple (Acer), birch (Betula), lime (Tilia), elm (Ulmus), hornbeam (Carpinus), beech (Fagus) and walnut (Juglans). Mistletoe was the main component of mesotrophic deciduous forests (Stuchlik et al. 1990). Viscum pollen was found quite often in the interglacial flora (JanczykKopikowa 1977). An examination of isopollen maps of Poland reveals that mistletoe percentages in the pollen assemblages are discontinuous and low (<0,6%). In the Holocene, Viscum pollen appeared about 9000-8500 years BP in central Poland, at the foot of the Tatra Mountains and in the Sudetes. Between 8500-7500 years BP, Viscum expanded gradually and about 3500 years BP its range spread across the whole country (Granoszewski et al. 2004). According to Jacomet and Kreuz (1999) the presence of mistletoe pollen grains indicates a mean temperature of the warmest month over 15ºC and very warm summer seasons. This taxon is also indicative of a mean temperature in January higher than -7ºC. Mistleote is a Eurasian plant; according to Hegi (1957) it is a Boreomeridial-Euroasian-Oceanic species. The present distribution of Viscum in Poland is presented on fig. 4 (Zając and Zając 2001). Many legends and customs are associated with mistletoe and the attributes that it is believed to possess. These have been used for practical and cultural purposes for ages. Among the special features of mistletoe that determine its cultural meaning, the most important is the location of this hemiparasite high between the earth and the heavens. This state of suspension means that mistletoe is positioned in a boundary zone, and results in a possibility of mediation and representation of the sacrum order that has always been radically separated from the mortal world. Another important feature is that it never yields its green colour, even if the parasitized tree loses its leaves. This everlasting green is a demonstration of permanency, invariability, and a defiance of the destructive influence of time (Kowalski 2007). Mistletoe was called a “golden branch”, because if its leaves are dried it changes colour from green to yellow-gold, associated with sunlight and eternity. It may also be linked to the underworld, another sign of mistletoe’s attachment to sacrum. Pliny described the circumstances accompanying the taking of mistletoe from oak by celtic Druids. A whitedressed priest would harvest mistletoe five days after a new moon using a special golden sickle. The severed plant should fall into white linen laid under the tree so as not to touch the ground, because if it did it would lose its sacred power. Later practises preserved this special care during the gathering of this plant. According to the Herbarium of Polish Marcin from Urzędów (in the original: Herbarz Polski Marcina z Urzędowa), mistletoe is collected not by cutting using metal tools, nor even by touching the plant itself, but by snapping the twigs through linen and then placing the plant onto another linen sheet laying on the ground. In Slavic tradition mistletoe was gathered during the evening before Christmas Eve. After climbing a tree with mistletoe, the plant was broken off using the head of an axe (not the blade) and was thrown to a man standing under the tree, so as not to let it touch the ground. Mistletoe twigs were put into beehives in order to obtain plenty of honey the following year (Kowalski 2007). In the Mazovia region mistletoe was burnt and smoke was spread around hives (www.bio-life.pl/art.7749). Mistletoe protected the home from insincere people. It was also said that you must leave a part of a branch on the host tree to avoid misfortune. According to present folk beliefs, a girl that refuses a kiss under mistletoe may provoke bad luck for herself. It was also believed that if a girl was kissed seven times during a day by seven men, then she would marry one of them that year (Kowalski 2007). Mistletoe is considered to be an aid for people in love and lovers; today, when there is so much tension, separation and divorce, this feature should not be neglected. Thus mistletoe that has been gilded or silver-plated, added to bouquets, decorations and ikebanas enters homes during Christmas 210 P l a n t s a n d C u l t u r e : s e e d s o f t h e c u l t u r a l h e r i t a g e o f E u r o p e - © 2 0 0 9 · E d i p u g l i a s . r. l . - w w w. e d i p u g l i a . i t J. MADEJA, K. HARMATA, P. KOŁACZEK, M. KARPIŃSKA-KOŁACZEK, K. PIĄTEK, P. NAKS time to bring us best wishes and joy. Surely mistletoe, especially the berries, can be sticky; incautious people may be caught as are flies. There is a well known saying in Poland “to be caught on glue” (in the original: “złapał się na lep”). Maybe this is mistletoe’s revenge for the fact that its twigs are taken nowadays without ceremony and with no respect for primeval rituals (Macioti 2006). Particular species are used by communities as food (Barlow 1987; Stypiński 1997). Leaves and twigs can be used as fodder for cattle and other animals. During famine, dried and ground mistletoe was added to flour from which bread was baked. Bastiaens et al. (2007), during investigations in a late-Mesolithic locality in Belgium, found large amounts of mistletoe twigs and ivy seeds. Researchers suggest that people collected these evergreen plants for ritual purposes or as fodder for animals during the winter. Pliny bequeathed an opinion known in ancient times according to which «Gauls believe that mistletoe used in drinks ensures fecundity and is a remedy for all poisons» (Questin 1994). In Polish folk medicine it is also regarded as “an antidote to all poisons and heaven’s gift”. Mistletoe taken from an apple tree or hawthorn protected from fear, especially children, if twigs were placed into a child’s bed then all nightmares were supposed to disappear. The plant most holy for the Druids was oak mistletoe. Pliny wrote: «For Druids there is no greater holiness than mistletoe that on a winter oak is born. Winter oak is for them a tree absolutely divine, it forms sacred groves venerated by them, and its leaves are essential at offering all sacrifices. If on one of the trees a mistletoe shrub appears, it is a certain sign that it came directly from heaven and the tree itself was chosen by one of the gods». The applications of mistletoe in medicine from Druid times till the beginning of the 20th century were summarized in a monograph by Tubeuf (1923). It was used as a cure for epilepsy, convulsions and to lower blood pressure. Extract from Viscum is helpful for arteriosclerosis and the spitting of blood. It was also prepared as injections that lower blood pressure. Often, especially in folk medicine, mistletoe was used in compresses for wounds and frostbites. Hence, nowadays drinking extracts from mistletoe is worthy of recommendation for many reasons. Likewise, wine that is made from 40 mg of leaves macerated for 10 days in one litre of dry white wine is also recommended. After filtration 100 mg of wine should be drunk twice or three times a day (Macioti 2006). Farmers in villages added leaves of this hemiparasitic plant to fodder, ensuring the fertility of their pigs, increasing milk production in cattle, and augmenting speed and strength in horses. Modern medicine has not forgotten the magical plant of the Celts. Indeed, it has even broadened its 5. - Distribution of bladder-nut (Staphylea pinnata (L.) in Poland (Zając, Zając 2001). usage. Preparations from mistletoe are used for curing cancer (Kołodziejak-Nieckuła 1994). A drug prepared from Viscum album called Iscador strengthens the immune system and inhibits tumour growth (Stypiński 1997) in anti-cancer therapy and against HIV. Oak mistletoe has the most extensive pharmacological effects as the medication Iscador Q (Iscador Qu). The most active components of this preparation are lectins and viscotoxins. They suppress the divisions of cancer cells and additionally mitigate the side effects of radiotherapy and chemotherapy (www.henryk.gower. pl/viscum.htm). In cytology mistletoe extract was used to change the cell division mechanism in maize seeds (Zea mays). Enormous polyploid cells were produced under the influence of different concentrations (0,1; 0,01; 0,001 %) of this extract (Stypiński 1967). Staphylea The origin of Latin name of genus Staphylea comes from shape of inflorescences, in greek language word ‘staphyle’ means bunch of grapes. Polish name ‘kłokoczka’ comes from characteristic sound called ‘klekot’ that can be heard when fruits are shaked by wind. If we take into consideration the aspects of distribution (Domin and Podpera 1928; Domin 1949; Gostyńska 1961a; Zając and Zając 2001) and ecology (Browicz 1959; Gostyńska 1961; Tylkowski 2007), bladder-nut is one of the most interesting Polish shrubs. It is the only representative of the genus Staphylea and the family Staphyleaceae in Poland. 211 P l a n t s a n d C u l t u r e : s e e d s o f t h e c u l t u r a l h e r i t a g e o f E u r o p e - © 2 0 0 9 · E d i p u g l i a s . r. l . - w w w. e d i p u g l i a . i t MYSTERIOUS PLANTS WITH UNUSUAL APPLICATIONS. CULTURAL AND ETHNOBOTANICAL STUDIES pink color, they are pollinated by flies. The fruit is two- or three-lobed capsule 3-10 cm long containing brown hardshelled seeds (fig. 6). Fossil remains of seeds and pollen grains of genus Staphylea were identified mainly in late Tertiary material. Latałowa (1994) mentioned 4 localities dated to the Holocene, whereas Środoń (1992) listed as many as 43 localities dated to Miocene and Pliocene from Poland. In the territory of Poland, the earliest reliable excavations where bladder-nut was found dates back to the turn of the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, comes from Prószcz Gdański (Latałowa 1994). Its seeds, threaded on a silver wire, formed a part of a rich necklace (fig. 7) (Pietrzak and Tuszyńska 1988, Latałowa 1994). The most interesting folk customs and religious rites connected with this plant have 6. - 1. Fructifying shrub. 2. Bark -olive-grey or brown with oblong white furrows. 3. survived the longest in the Inflorescences. 4. Flowers. 5. Pollen grain. 6. Fruit -bladdery multiseed capsule, 3-5 cm long. Podkarpacie region (S-E 7. - Seeds - with hard shells, containing oil substances. Photographs taken by: P. Naks (1,2,3), M. Karpińska-Kołaczek (4), P. Kołaczek (5,7), K. Piątek (6). Poland) (Gostyńska 1962), where the density of natural localities is the highest, and the The issue of its natural territorial range in our country populations are among the most numerous in the whole is still disputable. One of the reasons is the questionable country. Hence, this plant is often to be found there in the status of particular localities, which is caused by the fact household gardens. that for the centuries bladder-nut has been used by Bladder-nut’s wood was said to have the power to people as a utilitary plant (Šistek 1932a, 1932b; Jarvis keep away the evil spirits and the devil. Therefore it 1979). The presence of this species is limited to southern used to be carved into crosses, which were later hung and south-eastern part of Poland (Zając and Zając 2001) above the entrance doors, or put in the corners of the (fig. 5), at the northern limit of its range (Meusel et al. fields in order to prevent natural disasters and ensure a 1978). According to Kornaś and Wróbel (1972) these good harvest. The wood was also attached to the horns sites are treated as natural, however many modern of the cattle at the beginning of the pasturing season, in localities of this plant are of an antropogenic origin. order to protect them from evil spells and sickness. In Staphylea pinnata L. belongs to the east Mediterranean some places, bladder-nut’s wood was used to make pontic element (Hegi 1965). walking sticks and plungers for churning butter Bladder-nut is a termophilous calcicole shrub (Gostyńska 1962). growing up to 5 m. It is in blossom from May to June, The amazing white flowers were also used to and the seeds ripen from September to November. The decorate churches on festive days. In some places bark is olive-grey or brown with oblong white furrows. inflorescences of this plant are components of palms The leaves are arranged in opposite pairs, and pinnate prepared for ceremonial Palm Sunday and wreaths with 3-7 leaflets. The blossoms are hermaphrodite prepared for Corpus Christi octave. There was folk belief produced in drooping terminal panicles 5-10 cm long that putting them into the handkerchief of a beloved one with 5-15 blossoms on each inflorescence, the individual secures his love. People trusted in its power of protecting flowers are about 1 cm in their diameter, white and pale houses from thunderbolts. For all these reasons bladder- 212 P l a n t s a n d C u l t u r e : s e e d s o f t h e c u l t u r a l h e r i t a g e o f E u r o p e - © 2 0 0 9 · E d i p u g l i a s . r. l . - w w w. e d i p u g l i a . i t J. MADEJA, K. HARMATA, P. KOŁACZEK, M. KARPIŃSKA-KOŁACZEK, K. PIĄTEK, P. NAKS 7. - 1. Adornments made of bladder-nut seeds dated back to 3rd or the beginning of 4th century AD found in excavations in Prószcz Gdański (N Poland) (Pietrzak, Tuszyńska 1988 after Latałowa 1994, changed), 2. The rosary made by the Michaelite Fathers from Miejsce Piastowe. Collection of the Museum of Botanic Garden in Cracow. nut was often transplanted into gardens. As an outcome of this popularity, Staphylea has disappeared from the forests in some regions of Poland. Probably it was the Celts who first started to plant it on their grave-mounds (Heigi 1965). Because of their beautiful colour, shape and durability, the seeds were very popular. The aforementioned Celts used them to make various adornments. In the early Middle Ages (10th-12th century) they could have been used as food, together with the green parts of the plant. After the introduction of Christianity, the seeds were used to make rosaries (fig. 7), that is why the bladder-nut shrubs can often be found in cloister gardens. What is more, its seeds contain a lot of fat and can be used as a source of oil. They used to be ground and added into fodder, because it was believed that they can provide good health and longevity for farm animals. They were also used as medicine for ill children, as they were believed to have healing effects. However, overdosed they could cause vomits (Gostyńska 1962). At present, a research into the chemical compounds contained in the bladder-nut’s leaves, flowers, and seeds is carried out. It turns out that the flowers contain mostly different oxygenated aliphatic hydrocarbons; aldehydes, ketones, esters of higher fatty acids, and hexadecanoic acid with dominating content of tricosane and also of heneicosane, pentacosane, heptacosane, and nonacosane and some nonaliphatic hydrocarbons In the leaves one can found rutine and two sacharides, glucose and saccharose. Plant extracts possesses also many interesting secondary metabolites (polyphenols, flavonoids, hydroxycinnamic derivatives) (Laciková et al. 2008). It is also known that Staphylea pinnata possesses significant cytotoxic and antibacterial activity (Jantova et al. 2001; Laciková et al. 2007). There are more plants that were satisfying spiritual needs of man and were regarded as sacred, as a gift from heaven, that could be mentioned. People were making deal with them, sometimes full of adoration, respect and admiration, sometimes full of apprehension and fear; they were creating legends of them. All of that probably resulted from the fact that people considered themselves as an element of the surrounding nature, in which plants played, besides different beings, very important, practically an equal to people role. Acknowledgements Financial support from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education (grant 787/ Kultura 2007/2008/7). References Barlow 1987: B.A. Barlow - Mistletoes, in Biologist (Australia), 43, 1987, p. 261-269. Bastiaens et al. 2007: J. Bastiaens, K. Deforce, L. Meersschaert and B. Klinck - Two late Mesolithic sites along the river Scheldt (Doel, Belgium): focus on woodland and the use of Viscum album and Hedera helix, in 14th Symposium of the International Work Group for Palaeoethnobotany. Kraków, Poland 17-23 June 2007. Programme and abstracts, Kraków, W. Szafer Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Sciences, 2007, 118 p. Braid 1934: K.W. Braid - Bracken as a colonist, in Scottish Journal of Agriculture, 17, 1934, p. 59-70. Browicz 1959: K. Browicz - O rozmnażaniu się kłokoczki południowej (Staphylea pinnata L.), in Rocznik Dendrologiczny, 13, 1959, p. 125-130. Brown 1986: R.W. Brown - Bracken in the North York Moors: its ecological and amenity implications in national parks, in R.T. Smith and J.A. Taylor (Eds.) Bracken: Ecology, land use and control technology, Carnforth, The Parthenon Publishing Group Limited, 1986, p. 77-86. Callaghan et al. 1981: T.V. Callaghan, R. Scott and G.J. Lawson - An experimental assessment of native and naturalized plants as renewable sources of energy in Great Britain, in Contractors Coordination Meeting, Energy from Biomass Project, Luxemburg, Commission of the European Communities, 1981, p. 13-19. 213 P l a n t s a n d C u l t u r e : s e e d s o f t h e c u l t u r a l h e r i t a g e o f E u r o p e - © 2 0 0 9 · E d i p u g l i a s . r. l . - w w w. e d i p u g l i a . i t MYSTERIOUS PLANTS WITH UNUSUAL APPLICATIONS. CULTURAL AND ETHNOBOTANICAL STUDIES Caxton 1480: W. Caxton - Chronicles of England, London, 1480. Coquillat 1950: M. Coquillat - Au sujet du “pain de fougère” en Mâconnais, in Bulletin Mensuel de la Société Linnéenne de Lyon, 19, 1950, p. 173-176. Cox et al. 2007: E.S. Cox, R.H. Marrs, R.J. Pakeman and M.G. Le Duc - A multi-site assessment of the effectiveness of Pteridium aquilinum control in Great Britain, in Applied Vegetation Science, 10, 2007, p. 429-440. Domin 1949: K. Domin - Staphylea pinnata L. v Československu, in Hort. sanitat., 2(1), 1949, p. 34-35. Domin and Podpera 1928: K. Domin and J. Podpera Staphylea pinnata L, in Acta Botanica Bohemica, 6-7, 1928, p. 71, 107, 110, 114, 128. Fenwick 2006: G.R. Fenwick - Bracken (Pteridium aquilinum) toxic effects and toxic constituents, in Journal of the Sciences of Food and Agriculture, 46, 2006, p. 147-173. Gostyńska 1961: M. Gostyńska - Rozmieszczenie i ekologia kłokoczki południowej (Staphylea pinnata L.) w Polsce, in Rocznik Arboretum Kórnickiego, 6, 1961, p. 5-71. Gostyńska 1962: M. Gostyńska - Zwyczaje i obrzędy ludowe w Polsce związane z kłokoczką południową (Staphylea pinnata L.), in Rocznik Dendrologiczny, 16, 1962, p. 113-120. Göransson 1986: H. Göransson - Man and forests of nemoral broad-leaved trees during the Stone-Age, in Striae, 24, 1986, p. 143-152. Granoszewski et al. 2004: W. Granoszewski, M. Nita and D. Nalepka - Viscum album L.-Mistletoe, in A. RalskaJasiewiczowa, M. Latałowa, K. Tobolski, E. Madeyska, H.E. Wright Jr. and Ch. Turner (Eds.) - Late Glacial and Holocene History of Vegetation in Poland Based on Isopollen Maps, Kraków, W.Szafer Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Sciences, 2004, p. 237-243. Guarrera et al. 2005: P. M. Guarrera, G. Salerno and G. Caneva - Folk phytotherapeutical plants from Maratea area (Basilicata, Italy), in Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 99, 2005, p. 367-378. Hartig and Beck 2003: K. Hartig and E. Beck - The bracken fern (Pteridium arachnoideum (Kaulf.) Maxon) dilemma in the Andes of Southern Ecuador, in Ecotropica, 9, 2003, p. 3-13. Hendrick 1919: J. Hendrick - Bracken rhizomes and their food value, in Transactions of the Highland Society of Scotland, 31, 1919, p. 227-236. Hegi 1957: G. Hegi - Illustrierte Flora von Mittel Europa. Dicotyledones 3, München, Carl Hanser Verlag, 1957, 452 p. Hegi 1965: G. Hegi - Staphylea pinnata L., in Illustrierte Flora von Mittel-Europa. Band 5/1, Müchen, Carl Hanser Verlag, 1965, p. 258-262. Jackson 1981: L.P. Jackson - Asulam for control of eastern bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum) in lowbush blueberry fields, in Canadian Journal of Plant Science, 61, 1981, p. 475-477. Jackson and Smedley 2008: C.M. Jackson and J.W. Smedley - Medieval and post-medieval glass technology: seasonal changes in the composition of bracken ashes from different habitats through a growing season, in Glass Technology: European Journal of Glass Science and Technology Part A, 49, 2008, p. 240245. Jacomet and Kreuz 1999: S. Jacomet and A. Kreuz Archäobotanik, Stuttgart, Verlag Eugen Ulmer, 1999, 368 p. Janczyk-Kopikowa 1977: Z. Janczyk-Kopikowa - Flora plejstocenu, in J. Czermiński (Ed.) - Budowa geologiczna Polski. 2. cz. 3b. Katalog skamieniałości. Kenozoik, czwartorzęd, Warszawa, Instytut Geograficzny, Wydawnictwa Geograficzne, 1977, p. 43-70. Jantova et al. 2001: S. Jantova, M. Nagy, L. Ruekov and D. Grančai - Cytotoxic effects of plant extracts from the families Fabaceae, Oleaceae, Philadelphaceae, Rosaceae and Staphyleaceae, in Phytotherapy Research, 15(1), 2001, p. 22-25. Jarvis 1979: P.J. Jarvis - The introduction and cultivation of bladdernuts in England, in Garden History, 7(2), 1979, p. 65-73. Kołodziejak-Nieckuła 1994: E. Kołodziejczyk-Nieckuła - Wobjęciach jemioły, in Wiedza i Życie, 12, 1994, p. 24-28. Kornaś and Wróbel 1972: J. Kornaś and J. Wróbel Materiały do atlasu rozmieszczenia roślin naczyniowych w Karpatach polskich. 5. Staphylea pinnata L., in Rocznik Dendrologiczny, 26, 1972, p. 2731. Kowalski 2007: P. Kowalski - Kultura magiczna. Omen, przesąd, znaczenie, Warszawa, Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 2007, 654 p. Laciková et al. 2007: L. Laciková, J. Muselik, I. Mašterova and D. Grančai - Antioxidant activity and total phenols in different extracts of four Staphylea L. species, in Molecules 12(1), 2007, p. 98-102. Laciková et al. 2008: L. Laciková, I. Mašterová and I., D. Grančai - Bladdernut-determination of the content of selected secondary metabolites [Klokoč-Stanovenie obsahu vybraných sekundárnych metabolitov], in Farmaceuticky Obzor, 77(3), 2008, p. 69-73. Latałowa 1994: M. Latałowa - The archaeobotanical record of Staphylea pinnata L. from the 3rd/4th century A.D. in Northern Poland, in Vegetation History and Archaeobotany, 3(2), 1994, p. 121-125. Łuczaj 2004: Ł. Łuczaj - Dzikie rośliny jadalne Polski. Przewodnik survivalowy, Krosno, Chemigrafia, 2004, p. 148-150. Madeja et al. 2004: J. Madeja, K. Bałaga, K. Harmata and D. Nalepka - Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn - Bracken, in A. Ralska-Jasiewiczowa, M. Latałowa, K. Tobolski, E. Madeyska, H.E. Wright Jr. and Ch. Turner (Eds.) Late Glacial and Holocene History of Vegetation in Poland Based on Isopollen Maps, Kraków, W. Szafer Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Sciences, 2004, p. 327-335. Macioti 2006: M. Macioti - Mity i magie ziół, Kraków, Universitas, 2006, 344 p. Meusel et al. 1978: H. Meusel, E. Jäger, S. Rauschert and E. Weinert - Vergleichende Chorologie der Zentraleuropäischen Flora, Band II, Jena, Gustav Fischer Verlag, 1978, 286 p. Morris 1947: C. Morris - The journeys of Celia Fiennes, Long Riders’ Guild Press US, 2001, 376 p. Oberdorfer 1990: E. Oberdorfer - Pflanzensoziologische Exkursionsflora, Stuttgart, Verlag Eugen Ulmer, 1990, 1050 p. Oinonen 1976: E. Oinonen - The correlation between the size of Finnish bracken (Pteridium aquilinum (L.) 214 P l a n t s a n d C u l t u r e : s e e d s o f t h e c u l t u r a l h e r i t a g e o f E u r o p e - © 2 0 0 9 · E d i p u g l i a s . r. l . - w w w. e d i p u g l i a . i t J. MADEJA, K. HARMATA, P. KOŁACZEK, M. KARPIŃSKA-KOŁACZEK, K. PIĄTEK, P. NAKS Kuhn) clones and certain periods of site history, in Acta Forestalia Fennica, 83, 1976, p. 1-51. Page 1986: C.N. Page - The strategies of bracken as a permanent ecological opportunist, in R.T. Smith, J.A. Taylor (Eds.) - Bracken: Ecology, land use and control technology, Carnforth, The Parthenon Publishing Group Limited, 1986, p. 173-181. Pakeman et al. 2005: R.J. Pakeman, J.L. Small, M.G. Le Duc and R.H. Marrs - Recovery of Moorland Vegetation after Aerial Spraying of Bracken (Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn) with Asulam, in Restoration Ecology, 4, 2005, p. 718-724. Pieroni 2005: A. Pieroni - Gathering Food form Wild, in Sir G. Prance and M. Nesbitt (Eds.) - The Cultural History of Plants, New York, London, Routledge, 2005, p. 29-44. Pieroni and Quave 2005: A. Pieroni and C.L. Quave Traditional pharmacopoeias and medicines among Albanians and Italians in southern Italy: a comparison, in Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 101, 2005, p. 258270. Pietrzak and Tuszyńska 1988: M. Pietrzak and M. Tuszyńska - Periode Romaine Tardive (Pruszcz Gdański 7), in W. Hensel (Ed.) - Inventaria Archeologica Pologne. Fasc LX: PL, Warszawa-Łódź, PWN, 1988, p. 369-373. Pitman and Weber 1998: R. Pitman and J. Weber Bracken as a Peat Alternative, in The Forestry Authority, Edinburgh, Forestry Practice, 1998, p. 1-6. Questin 1994: M. Questin - Medycyna Druidów, Kraków, Wydawnictwo Kastel, 1994, 196 p. Stickney 1986: P.F. Stickney - First decade plant succession following the Sundance Forest Fire, northern Idaho, in USDA Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station, General Technical Report, p. 1-197. Stuchlik et al. 1990: L. Stuchlik, A. Szynkiewicz, M. Łańcucka-Środoniowa and E. Zastawniak - Wyniki dotychczasowych badań paleobotanicznych trzeciorzędowych węgli brunatnych złoża “Bełchatów”, in Acta Palaeobotanica, 30, 1990, p. 259-305. Stypiński 1981: P. Stypiński - Zależność składu chemicznego Viscum album L. subsp. album od właściwości gleby i natężenia ruchu pojazdów samochodowych na Pojezierzu Mazurskim, Olsztyn, Wyższa Szkoła Pedagogiczna, 1981, 77 p. Stypiński 1997: P. Stypiński - Biologia i ekologia jemioły pospolitej (Viscum album, Viscaceae) w Polsce, in Fragmenta Floristica et Geobotanica Series Polonica, Suppl. 1, 1997, p. 3-115. Šistek 1932a: V. Šistek - Klokoč (Staphylea pinnata L.), in Česky Včelař, 66(4), 1932, p. 133. Šistek 1932b: V. Šistek - Klokoč (Staphylea pinnata L.), in Česky Včelař, 66(5), 1932, p. 177. Środoń 1992: A. Środoń - Kłopoty z kłokoczką (Troubles with Staphylea pinnata L.), in Wiadomości Botaniczne 36, 1992, p. 63-67. Taylor 1986: J.A. Taylor - The bracken problem: a local hazard and global issue, in R.T. Smith and J.A. Taylor (Eds.) - Bracken: ecology, land use and control technology, Carnforth, The Parthenon Publishing Group Limited, 1986, p. 21-42. Thomson 2000: J.A. Thomson - Morphological and genomic diversity in the genus Pteridium (Dennstaediaceae), in Annals of Botany - London, 85, 2000, p. 77-99. Thomson and Alonso-Amelot 2002: J.A. Thomson and M.E. Alonso-Amelot - Clarification of the taxonomic status and relationships of Pterdium caudatum (Dennstaediaceae) in Centra, and south America, in Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 140, 2002, p. 237-248. Tubeuf 1923: K. V. Tubeuf - Monographie der Mistel, München-Berlin, R. Oldenburg, 1923, 832 p. Tylkowski 2007: T. Tylkowski - Stratification conditions determining seed dormancy release of European bladder nut (Staphylea pinnata L.), in Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae, 76(2), 2007, p. 95-101. Viegi et al. 2003: L. Viegi, A. Pieroni, P.M. Guarrera and R. Vangelisti - A review of plants used in folk veterinary medicine in Italy as basis for a databank, in Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 89, 2003, p. 221244. Yamada et al. 2007: K. Yamada, M. Ojika and H. Kigoshi - Ptaquiloside, the major toxin of bracken, and related terpene glycosides: chemistry, biology and ecology, in Natural Product Reports, 24, 2007, p. 798-813. Zając and Zając 2001: A. Zając and M. Zając (Eds.) Distribution Atlas of Vascular Plants in Poland, Kraków, Laboratory of Computer Chorology, Institute of Botany, Jagiellonian University, 2001, 714 p. 215 P l a n t s a n d C u l t u r e : s e e d s o f t h e c u l t u r a l h e r i t a g e o f E u r o p e - © 2 0 0 9 · E d i p u g l i a s . r. l . - w w w. e d i p u g l i a . i t