* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Digestive Function of the Large Intestine

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

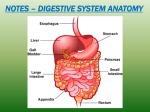

Digestive Function of the Large Intestine The major digestive role of the large intestine involves propulsion-pushing fecal matter toward the anus and then out of the body. Chyme, which stays in the large intestine for 12 to 24 hours, contains few nutrients. Enteric bacteria are responsible for a small amount of digestion. The bacterial flora creates vitamins required for normal metabolism, such as certain B vitamins and vitamin K. Most of the remaining water and some electrolytes (especially sodium and chloride) are recycled. Structure Action Outcome Lumen Bacterial degradation of chyme Breaks down undigested proteins, components carbohydrates, and amino acids into substances that can be absorbed and detoxified by the liver or eliminated in feces; synthesizes vitamin K and some B vitamins Mucosa Mucus secretionAbsorption Lubricates colon; protects mucosaAbsorbs water, solidifies feces, and helps maintain water balance in body; absorbed solutes include ions and certain vitamins Muscularis externa Haustral Muscle contractions move contents churningPeristalsisDefecation between haustrumsContractions of reflex circular and longitudinal muscles propel contents along length of colon; Propels contents into sigmoid colon and rectumContractions in sigmoid colon and rectum eliminate feces Ileostomy It may surprise you that the large intestine can be completely removed without significantly affecting digestive functioning. For example, if colon cancer necessitates the removal of the large intestine, anileostomy can be performed, in which the terminal ileum is moved out to the abdominal wall. A sac is then attached to the abdominal wall to collect eliminated food residues. Mechanical Digestion Mechanical digestion in the large intestine begins when chyme moves from the ileum into the cecum, an activity regulated by the ileocecal valve. This sphincter is usually partially closed, allowing slow movement of chyme into the large intestine. Right after we eat, the gastroileal reflex escalates peristalsis in the ileum, which forces whatever chyme is in the ileum into the cecum. The activity of the hormone gastrin also relaxes the ileocecal valve. When the cecum is distended with chyme, contractions of the ileocecal sphincter strengthen. Once chyme enters the cecum, colon movements begin. As food residues pass the ileocecal valve, they fill the cecum and gather in the ascending colon. The presence of food residue in the colon stimulates slowmoving haustral contractions (haustral churning). These sluggish segmentations, primarily in the transverse and descending colons, occur about every 30 minutes and last about one minute. When a haustra is distended with chyme, its muscle contracts, pushing the residue into the next haustra. The movements also mix the food residue, which helps the large intestine absorb water. The large intestine also has peristaltic movements, but they are slower than in more proximal portions of the alimentary canal, at a rate of from three to 12 contractions per minute. The third type of movement in the large intestine is called mass movements (mass peristalsis). These drawn-out, slow-moving, but strong peristaltic waves start around the middle of the transverse colon and quickly force the contents of the colon into the rectum. Mass movements usually occur three or four times per day, either while we eat or immediately afterward. Distension in the stomach and the breakdown products of digestion in the small intestine provoke the gastrocolic or duogenocolic reflex, which increases motility, including mass movements, in the colon. Fiber in the diet both softens the stool and increases the power of colonic contractions, optimizing the activities of the colon. Chemical Digestion The glands of the large intestine secrete only mucus; they do not secrete digestive enzymes. So chemical digestion in the large intestine occurs only through the activity of the bacteria in the lumen of the colon. Bacteria ferment residual carbohydrates in the chyme and discharge the hydrogen sulfide, carbon dioxide, and methane gases that help create flatus (gas) in the colon(flatulence refers to excessive flatus). Some of these gases, including dimethyl sulfide, have foul odors. Each day, about 500 mL of flatus is produced in the colon. Much more is produced when we eat some fiber-rich foods such as beans.