* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download epistemology - mrsmcfadyensspace

Survey

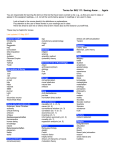

Document related concepts

Transcript

EPISTEMOLOGY • Philosophers are interested in knowledge. This will not surprise you – even if you have never studied any philosophy before, you will expect that philosophers are interested in gaining philosophical knowledge – just as historians seek historical knowledge, and mathematicians seeks mathematical knowledge, biologists seeks biological knowledge, and so on. EPISTEMOLOGY • Clearly a philosopher does want philosophical knowledge. But there is a more important point to make here. Historians and mathematicians and biologists want knowledge – but they don’t ask what ‘knowledge’ is. They take it for granted that there is knowledge, and then set out to find it. • Philosophers are different. They ask questions such as ‘what is knowledge?’, and ‘is it possible to have knowledge that is 100% reliable – knowledge that is absolutely certain?’. This is what we are to be studying in this Epistemology unit. EPISTEMOLOGY • Let’s see how this fits in with a definition of ‘philosophy’. • Philosophy is an activity. • When we are doing philosophy, we are trying to do two things: • We are trying to clarify our important beliefs. • We are trying to justify our important beliefs. EPISTEMOLOGY • One of the important beliefs that we all have is that knowledge is possible – that we can gain knowledge by various means. • One of the reasons for studying Philosophy is, after all, that you want to have knowledge of Philosophy. But you also want to have knowledge of many other things: whether it will rain today; what books you need for your course; when the class begins; who can tell you what you need to revise for the exam; where the exam will be held; and so on. EPISTEMOLOGY • We go through life taking for granted that knowledge is possible – and that gaining knowledge is straightforward – so that by the time we are in our teens, we have already learned an enormous amount (and that one of the most important differences between a 16-year-old person and a 16week-old person is the massive amount of learning – ‘knowledge-acquisition’ – that the 16-week-old has ahead of him or her). EPISTEMOLOGY • If we think about the definition of ‘philosophy’ given above, we can see, then, that there are two tasks for philosophers: • Getting clear what it means to say that we have knowledge (this is the ‘clarifying’ part). • Proving that knowledge is possible (this is the ‘justifying’ part). EPISTEMOLOGY • Philosophers who deal with these questions are ‘epistemologists’. The word ‘epistemology’ was introduced into philosophy by a nineteenth century Scottish philosopher, James Ferrier. It is made up of two Greek words. In Greek ‘episteme’ means ‘knowledge’, and ‘logos’ means ‘explanation, or study’. So ‘epistemology’ is the study of knowledge. EPISTEMOLOGY • It may seem that the epistemologist’s questions aren’t worth asking. How can we doubt that we have knowledge? How can there be any question about what knowledge is? This raises an important point about philosophy. Philosophers tend to take nothing for granted. Philosophers will generally be very suspicious of the notion that ‘it’s just obvious’. • What do we mean when we say that we have knowledge? EPISTEMOLOGY • Think about the ways in which we use the verb ‘to know’: • I know that David Hume died in 1776. • I know how to use this software. • I know who committed the ‘Jack the Ripper’ killings. • I know the quickest way to get from Glasgow to Edinburgh. • I know French. • I know France. EPISTEMOLOGY • This short list contains three different uses of the word to ‘know’. So if we are to clarify what it means to say that we have knowledge, then we will have to start by getting clear what are these three, and how they differ. EPISTEMOLOGY • Firstly, there is the use of ‘know’ in example 1: I know that … – where what comes after the word ‘that’ is a statement (also known as a ‘proposition’). In the case of example 1, we have three things: • The proposition ‘David Hume died in 1776’. • The person who is making the claim – ‘I’. • The relationship between the person and the proposition – here a relation of ‘knowing’. EPISTEMOLOGY • Notice how this is different from example 2. In example 2, what is known is not a fact (a true proposition such as ‘David Hume died in 1776’), but rather how to do something. This is the kind of knowledge that we have when we have ‘know-how’. So if I know how to write HTML code on a computer, or how to bake a cake or solve simultaneous equations, then I have this kind of knowledge. EPISTEMOLOGY • Example 3 is really just the same kind of knowledge as was example 1 – what we call ‘propositional knowledge’. Whereas in example 2 the target for knowledge is some skill, such as a mathematical skill, or a baking skill, in examples 1 and 3 the target for knowledge is a proposition – ‘David Hume died in 1776’, or ‘The Prince of Wales was Jack the Ripper’. EPISTEMOLOGY • Example 4 can be thought of either as propositional knowledge, or as know-how. ‘I know the quickest way to get from Glasgow to Edinburgh’ could be set out as: • I know how to get from Glasgow to Edinburgh by the quickest method. • I know that the quickest way to get from Glasgow to Edinburgh is by hiring a helicopter. EPISTEMOLOGY • People who are training to drive black taxis have to ‘do the knowledge’. What this means is that they have to know their way around the city so well that they can pass a rigorous examination before getting a licence. Here again we can think of their knowledge in one of two ways: the Edinburgh taxi driver needs to know how to get from Waverley station to the Scottish Parliament; alternatively s/he has to know that Waverley Station is at Waverley Bridge, and the Scottish Parliament is at Holyrood. EPISTEMOLOGY • ‘I know French’ (example 5) is, of course, an example of know-how. What it means is ‘I know how to speak French’ EPISTEMOLOGY • Finally, example 6 is importantly different. ‘I know France’ means ‘I am familiar with France, having been there’. This is really a third way of using the verb ‘to know’: it is what philosophers call knowledge by acquaintance. If I say that I know the paintings of Gauguin, or that I know the man who wrote the book or know the Beethoven Violin Concerto, then this means that I am acquainted with – I have been in some kind of contact with the man (whom I have met), the paintings (which I have seen), or the music (which I have heard). Notice how our Edinburgh cabbie can also be said to have knowledge by acquaintance (of course: he needs to be very familiar with Edinburgh).