* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download CT_19

Currency War of 2009–11 wikipedia , lookup

Reserve currency wikipedia , lookup

Currency war wikipedia , lookup

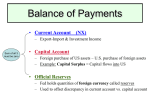

Foreign exchange market wikipedia , lookup

Bretton Woods system wikipedia , lookup

Foreign-exchange reserves wikipedia , lookup

International monetary systems wikipedia , lookup

Fixed exchange-rate system wikipedia , lookup

Modern Principles: Macroeconomics Tyler Cowen and Alex Tabarrok Chapter 19 International Finance Slide 1 of 54 Copyright © 2010 Worth Publishers • Modern Principles: Macroeconomics • Cowen/Tabarrok Introduction • In this chapter we build on the principles of • international trade. We learn… What it means when we are told that the dollar is “strong” or “weak”. What a trade deficit is and if it is worse than a trade surplus. Why people protest against the World Bank and the IMF. • What are these institutions? Slide 2 of 54 Introduction • There are three principles underlying this chapter. 1. 2. 3. Gains from trade occur when people trade across different countries with different currencies. The rate of saving is a key variable. Market equilibrium means that, at the margin, the gains from holding or spending one currency are equal to holding or spending some other currency. Slide 3 of 54 U.S. Trade Deficit and Your Trade Deficit • • • Trade deficit (surplus)—The value of a country’s imports (exports) exceeds the value of its exports (imports). Surplus good, deficit bad—right? Not necessarily All of us run trade deficits with our grocery store, gas station… These deficits are balanced with a trade surplus with someone else…those who buy our labor. Same is true for the U.S. • What if the U.S. runs a deficit with the world as a whole? Slide 4 of 54 The Balance of Payments • Balance of payments: yearly summary of all economic transactions between residents of one country and residents of the rest of the world. Goods and services Transfers of financial claims: stocks, bonds, loans, and ownership rights. When there is no borrowing/lending, trade deficits must be balanced with other trade surpluses. Slide 5 of 54 The Balance of Payments • A trade deficit with the rest of the world is possible if a country can borrow from the rest of the world. This borrowing is called a capital inflow. • A trade surplus is possible if on balance U.S. residents lend money to the rest of the world. This lending is called a capital outflow. • Capital surplus (deficit)—when the inflow of foreign capital is greater (less) than the outflow of capital to other nations. Slide 6 of 54 The Balance of Payments • Another way a trade deficit can be financed Sell assets and spend the proceeds. • The following identities put this all together. For individuals: Earning - Spending debt assets cash reserves For countries: Current account Capital account official reserves • Let’s look at each of these in turn. Slide 7 of 54 The Balance of Payments • The Current Account—sum of three items 1. Balance of trade 2. Net income of capital held abroad • Profits • Interest • Dividends 3. Net transfer payments, such as foreign aid All transactions are completed in the current period. Categories (2) and (3) tend to be stable. Balance of trade and capital account are where the action is. Slide 8 of 54 The Balance of Payments • The Capital Account (Financial Account)— measures changes in foreign ownership of domestic assets, physical or financial. Investments are divided into three categories: 1. Foreign direct investment (FDI): Plants or other specific tangible operations in the U.S. 2. Portfolio investment: Purchase of U.S. stocks, bonds, or other asset claims. 3. Other investment: Movements of bank deposits from another country to the U.S. Slide 9 of 54 The Balance of Payments • The Official Reserves Account—Includes U.S. government holdings of… Foreign currencies Gold reserves International Monetary Fund claims—Special drawing rights (SDRs) Sometimes governments stockpile U.S. dollars or other currencies such as the Euro. • Chinese government currently holds more than $1 trillion in dollar-denominated assets. Slide 10 of 54 The Balance of Payments • How the pieces fit together Suppose Wal-Mart buys more toys from China • U.S. current account deficit increases. • Chinese receive the dollars. If they… Buy U.S. goods→ ↓ current account deficit. Buy U.S. government bonds → ↓ U.S. capital account deficit. Send the money to a bank in the U.S. → ↓ U.S. capital account deficit. Keep the money in a Chinese bank → ↓ U.S. reserves. Conclusion: The B of P will always balance. Slide 11 of 54 The Balance of Payments • Two Sides, One Coin Usually major changes in the balance of payments come through the current account and the capital account. Implication: A country that is running a current account deficit is also running a capital account surplus. • That is, current account deficits in the U.S. are financed by foreigners investing in the U.S. • The following figure shows this clearly. Slide 12 of 54 The Balance of Payments • Two Sides, One Coin (cont.) U.S. Balance of Payments 1980-2005 1000 800 Capital Account 600 400 200 0 -200 -400 -600 Current Account -800 -1000 1980 1982 1984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 Year Current Account (in Billions) Capital Account (in Billions) Source: Bureau of Economics Analysis Slide 13 of 54 The Balance of Payments • Two Sides, One Coin (cont.) Is our trade deficit a problem? → Same question: Is our capital surplus a problem? Two Views • “The U.S. is a great place to invest.” Capital account surplus → current account deficit Investment → ↑ wealth • “Americans are foolishly saving too little.” Tied to government budget deficit. Results in lower future living standards. Slide 14 of 54 The Balance of Payments • The Bottom Line on the Trade Deficit Most economists believe that the trade deficit per se is not a problem. A trade deficit might indicate or signal a problem of low savings. • Trade restrictions are unlikely to solve a savings problem. If Americans are saving too little, a better solution: • Tax hikes and/or • Spending cuts Slide 15 of 54 CHECK YOURSELF An inhabitant of Lincoln, Nebraska, buys a German sports car for $30,000. What changes does this make to the U.S. current account? A German sports car manufacturer opens a new plant in South Carolina. How does this affect the U.S. current account and capital account? Is there a link between a current account deficit and a capital account surplus? Slide 16 of 54 What Are Exchange Rates? • Exchange rate: price of one currency in another currency (February 28, 2007) Slide 17 of 54 What Are Exchange Rates? • Exchange Rate Determination in the Short Run $/¥ Supply of Yen Exchange rate is determined by supply and demand just like any other commodity. $0.0085 Demand for Yen Market for Yen Quantity of Yen Slide 18 of 54 What Are Exchange Rates? • Factors that Shift the Demand Curve 1. An increase (decrease) in the demand for a country’s exports increases (decreases) the value of its currency. 2. The more desirable (undesirable) a country is for foreign investment, the higher (lower) the value of that country’s currency. 3. An increase in the demand to hold dollar reserves boosts the value of the dollar. Let’s use the supply and demand model to illustrate each of these… Slide 19 of 54 What Are Exchange Rates? 1a. U.S. residents order more Toyotas $/¥ Supply of yen ↑ demand for Japan’s exports → ↑ value of the yen $0.0090 Demand for yen w/↑ orders of Toyotas $0.0085 Demand for yen Market for Yen Quantity of Yen Slide 20 of 54 What Are Exchange Rates? 1b. U.S. residents order fewer Toyotas $/¥ Supply of yen ↓ demand for Japan’s exports → ↓ value of the yen Demand for yen w/↓ orders of Toyotas $0.0085 $0.0080 Demand for yen Market for Yen Quantity of Yen Slide 21 of 54 What Are Exchange Rates? 2. Mexico becomes a better investment $/peso Supply of pesos The Mexican peso ↑ in value 0.090 0.075 Demand for peso w/↑ foreign investment Demand for pesos Market for Pesos Quantity of Pesos Slide 22 of 54 What Are Exchange Rates? 3. Change in the demand for dollar reserves Many governments prefer to hold dollars as a means of saving and enjoying liquidity. Of all currencies held in the world U.S. dollars comprise 2/3. The Swiss franc is also another global currency. • It has long been regarded as a “safe haven” currency. Let’s use our model to see this… Slide 23 of 54 What Are Exchange Rates? 3. Japan ↑ its demand for $ reserves ¥/$ Supply of dollars The U.S. $ increases in value 120.000 Demand for dollars w/↑ demand for U.S. $ reserves 118.225 Demand for dollars Market for Dollars Quantity of dollars Slide 24 of 54 What Are Exchange Rates? • Factors That Shift the Supply Curve Depreciation: A decrease in the price of a currency in terms of another currency. Central banks have the power to increase the supply of their country’s currency. • Zimbabwe had been printing trillions of Zimbabwe dollars. By 2006: ↓ U.S.$/Z$ → 0.018 to 0.00001 • If the Federal Reserve increases the supply of U.S. dollars → depreciation of $. • Let’s use the model once more… Slide 25 of 54 What Are Exchange Rates? • Fed Increases the Supply of Dollars €/$ The U.S. $ depreciates against the euro Supply of dollars Supply of dollars w/↑ money supply 0.76 0.68 Demand for dollars Market for Dollars Quantity of dollars Slide 26 of 54 What Are Exchange Rates? • Exchange rate determination in the long run Important principle: Equilibrium requires that the benefit of spending should be the same. • Whether in Chicago, Berlin, or Paris. • Whether on goods, services, or investments. Nominal exchange rate: rate at which one currency can be exchanged for another. Real exchange rate: rate at which goods and services of one country can be exchanged for the goods and services of another. Slide 27 of 54 What Are Exchange Rates? • Exchange rate determination in the long run (cont.) Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) Theorem: The real purchasing power of a money should be about the same, whether it is spent at home or converted into another currency and spent abroad. Two predictions of the PPP: • Toyotas should cost the same in Tokyo or Chicago. • A general bundle of goods should cost the same everywhere. Slide 28 of 54 What Are Exchange Rates? • Exchange rate determination in the long run (cont.) • • • PPP is an application of the law of one price. Law of one price—If trade were free, then identical goods should sell for about the same price throughout the world. In order for this to happen prices and exchange rates have to adjust to equalize the rate of return. These adjustments will determine the real exchange rate. Slide 29 of 54 What Are Exchange Rates? • Exchange rate determination in the long run (cont.) PPP is only approximately true. Why? 1. Transportation costs PPP only applies when goods can be transported easily. Services are a good example; It’s possible but costly to fly to London for a haircut. 2. Some goods cannot be shipped. Sipping coffee in Paris is different than sipping it in Mobile, Alabama. Apartments Slide 30 of 54 What Are Exchange Rates? • Exchange rate determination in the long run (cont.) PPP is only approximately true. Why? (Cont.) 3. Tariffs and quotas—To the extent governments restrict trade, prices will not equalize across countries. PPP holds more tightly in the long run than in the short run. • In the long run, entrepreneurs are able to bring prices closer. Slide 31 of 54 What Are Exchange Rates? • Short-run movements within the boundaries set by PPP About $1.9 trillion in foreign exchange transactions take place on a typical day. • Most trades are speculative. • Daily price movements are set largely by psychology and expectations. • Some traders are simply guessing what other traders are going to do. • Sometimes these short-run movements are called “noise.” Slide 32 of 54 CHECK YOURSELF If the U.S. dollar is a safe haven currency and risk increases, what does this do to the value of the dollar: send it higher or lower? If the Federal Reserve increases the U.S. money supply, what will this do to the value of the dollar compared to the euro? If purchasing power parity holds and the nominal exchange rate is one pound for two dollars, how much should a Big Mac cost in London if a Big Mac costs $4.00 in New York? How does a tariff affect purchasing power parity? Slide 33 of 54 How Exchange Rates Affect Aggregate Demand • Monetary Policy Suppose the Fed increases M through open market operations. • Short-run The supply curve for dollars shifts to the right → depreciation of the dollar. A depreciation of the dollar → ↑ Exports ↑ Exports → ↑ AD • Long-run Money is neutral → ↑ domestic prices to match ↑ M If ↑ M is permanent → U.S. p rises. Slide 34 of 54 How Exchange Rates Affect Aggregate Demand • A depreciation ↑ AD in the short run Inflation rate Solow growth curve New SRAS (pe = 7%) Longrun c 7% 4% b SRAS (pe = 2%) Short-run: a → b ↑p: 2% → 4% Long-run: b → c ↑p: 4% → 7% 2% a AD(M v 10%) Short-run AD(M v 5%) 3% 6% Real GDP growth rate Slide 35 of 54 How Exchange Rates Affect Aggregate Demand • Dynamics of the Real Exchange Rate Once a Fed action is announced, the dollar moves on international currency markets within minutes. Because domestic prices do not move as quickly, the dollar has lower value → ↓ real exchange rate. In the long run as prices adjust, the real exchange rate returns to the PPP value. The following figure illustrates this... Slide 36 of 54 How Exchange Rates Affect Aggregate Demand • Dynamics of the Real Exchange Rate Slide 37 of 54 How Exchange Rates Affect Aggregate Demand • Fiscal Policy Government borrows more money → ↑ demand for loanable funds → ↑ interest rates ↑ interest rates attract foreign capital inflow → appreciation in the U.S. dollar. Appreciation in the U.S. dollar reduces U.S. exports → trade deficit. Result: Twin deficits Using fiscal policy to boost AD is partially offset by the rise in the trade deficit. Conclusion: Fiscal policy is less justified in an open economy. Slide 38 of 54 CHECK YOURSELF In the short run, what will happen to exports if the Fed increases the money supply? What will happen in the long run? Which tends to be more effective in an open economy: monetary policy or fiscal policy? Slide 39 of 54 Fixed vs. Floating Exchange Rates • Definitions: Floating exchange rate: determined primarily by market forces. Fixed (pegged) exchange rate: the central bank has promised to convert its currency at a fixed rate. Dollarization: occurs when a foreign country uses the U.S. as its currency. • Today, floating exchange rates are most common. Slide 40 of 54 Fixed vs. Floating Exchange Rates • Fixed exchange rate systems take three forms: 1. Adopting the money of another country. • Called “dollarization” • Panama, Ecuador, and El Salvador • Disadvantage: the country must buy and save sufficient dollars. • Advantage: Once in place, the country receives U.S. monetary policy. Avoids high inflation that has plagued other Latin American countries Slide 41 of 54 Fixed vs. Floating Exchange Rates • Fixed exchange rate systems take three forms: (cont.) 3. Backing a currency with a high level of reserves and promising convertibility at a certain rate. • Holding sufficient reserves makes the policy credible. • Central bank buys and sells its country’s currency to maintain the pegged rate. • Dirty float: currency isn’t pegged but kept within a certain range. Slide 42 of 54 Fixed vs. Floating Exchange Rates • Fixed exchange rate systems take three forms: (cont.) 2. Setting up a currency union. • A country gives up its own currency for a common currency, e.g., the euro. Larger countries saw it as a way to unify Europe economically. Smaller countries saw it as a way to obtain a more stable currency. Slide 43 of 54 Fixed vs. Floating Exchange Rates • The Problem with Pegs Thailand, Indonesia, Brazil, and Argentina attempted pegs to the U.S. dollar. • They were all broken by speculators. • These countries could not match U.S. economic policy. Argentina couldn’t control inflation → ↓ value of their peso. To maintain the peso at the pegged rate, the Argentine central bank would have to buy large amounts of pesos with U.S. dollars. Slide 44 of 54 Fixed vs. Floating Exchange Rates • The Problem with Pegs (cont.) Speculators didn’t believe that the pegs could be maintained. • They would buy dollars instead. • This would maintain value of the dollar and keep the Argentine peso below the peg. • Argentina did not have enough dollars to maintain the peg. Conclusion: Without an economy as sound as the U.S., countries cannot peg their currency to the dollar in the long run. Slide 45 of 54 CHECK YOURSELF When the value of a country’s currency is determined by the forces of supply and demand, is this a floating exchange rate or a fixed exchange rate? Who controls the monetary policy of the European Union? Slide 46 of 54 What Are the IMF and the World Bank? • International Monetary Fund (IMF) Created after the end of WWII to serve as lender of last resort. • When countries face financial difficulties, IMF steps in to organize a rescue package. Historically the President is a European. Income comes from… • Contributions from each member government. • Income from its loans. Slide 47 of 54 What Are the IMF and the World Bank? • International Monetary Fund (IMF) (cont.) Controversial • Critics: Argue that it forces borrowing governments to adopt painful economic policies. Cut government spending Tighten monetary policy Raise interest rates In other words they force a contractionary economic policy when perhaps expansionary policies were called for. Slide 48 of 54 What Are the IMF and the World Bank? • International Monetary Fund (IMF) (cont.) Controversial (cont.) • Defenders: IMF advice is more subtle than sometimes portrayed. Tough fiscal reforms are sometimes needed. Borrowing countries do not follow the advice even if it is good advice. Slide 49 of 54 What Are the IMF and the World Bank? • The World Bank (IBRD, International Bank for Reconstruction and Development) Also set up after WWII. Designed to facilitate the flow of capital to poor countries. • 2006—Loans to developing nations = $21 billion; loan repayments = $15 billion. Currently its largest borrower is China. Other top borrowers: India, Brazil, Mexico, and Turkey. Slide 50 of 54 What Are the IMF and the World Bank? • The World Bank (cont.) Also controversial • Critics: Not enough attention is given to whether projects deliver promised benefits. Lent funds often end up in developed countries as the funds are spent on materials and experts from countries that control the bank. Accountability is low because each year another round of loans will be made in any case. Slide 51 of 54 What Are the IMF and the World Bank? • The World Bank (cont.) Also controversial (cont.) • Defenders—argue that the bank has responded to its critics. Improved environmental record Avoided many previous mistakes Foreign aid is difficult to succeed at; overall the World Bank is a force for good. • Final comment: The IMF and the World Bank are not as important—for better or worse—as many people think. Slide 52 of 54 Takeaway • Trade deficits are not necessarily a problem • • • unless the country is investing foolishly or not spending enough. The trade balance is one side of the coin, with the capital account serving on the other side. Exchange rates are set in active markets following the laws of supply and demand. Monetary policy can affect the real exchange rate in the short run but not in the long run. Slide 53 of 54 Takeaway • In the long run exchange rates are set by • purchasing power parity. Both monetary and fiscal policy affect a country’s real exchange rate in the short run. These effects change AD by affecting exports, imports, and the flow of capital from one country to another. Most countries have floating exchange rates. Fixed or pegged exchange rates are possible but difficult to maintain over the long run. • Combinations of currency unions and floating exchange rates have become the norm. Slide 54 of 54