* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Mill Fall 2005

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

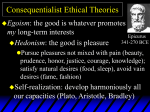

Poli 64 Modern Political Thought TURN YOUR PHONE OFF! PARLIAMENT ENACTS THE STAMP ACT: November 1, 1765 In the face of widespread opposition in the American colonies, Parliament enacts the Stamp Act, a taxation measure designed to raise revenue for British military operations in America. Modern thought Jeopardy! The answer: The “tendency of society to impose… its own ideas and practices as rules of conduct on those who dissent from them” The question?: What is MAJORITY RULE or FORCING PEOPLE TO BE FREE? OR IS IT THE TYRANNY OF THE MAJORITY? The Classical and the Modern Political Ideals We can no longer enjoy the liberty of the ancients, which consisted in an active and constant participation in collective power. Our freedom must consist of peaceful enjoyment and private independence. The share which in antiquity everyone held in national sovereignty was by no means an abstract presumption as it is in our own day. The will of each individual had real influence: the exercise of this will was a vivid and repeated pleasure. Consequently the ancients were ready to make many a sacrifice to preserve their political rights and their share in the administration of the state. Everybody, feeling with pride all that his suffrage was worth, found in this awareness of his personal importance a great compensation. This compensation no longer exists for us today. Lost in the multitude, the individual can almost never perceive the influence he exercises. Never does his will impress itself upon the whole; nothing confirms in his eyes his own cooperation. The exercise of political rights, therefore, offers us but a part of the pleasures that the ancients found in it, while at the same time the progress of civilization, the commercial tendency of the age, the communication amongst peoples, have infinitely multiplied and varied the means of personal happiness. It follows that we must be far more attached than the ancients to our individual independence. For the ancients when they sacrificed that independence to their political rights, sacrificed less to obtain more; while in making the same sacrifice we would give more to obtain less. The aim of the ancients was the sharing of social power among the citizens of the same fatherland: this is what they called liberty. The aim of the moderns is the enjoyment of security in private pleasures; and they call liberty the guarantees accorded by institutions to these pleasures. Benjamin Constant, 1816 The eclipse of republicanism and the “liberty of the ancients,” and the triumph of LIBERALISM *Revision of historiography: Stadial accounts of development, critique of the classical ideal (e.g. Athens over Sparta), emergence of “Whig history” *Ascendancy of “rights” discourse *Ascendancy of “political economy” *Development of capitalist and socialist economic theory *Popular government as means of individual satisficing (and the decline of collective greatness) “Classical liberty” becomes the purview of romantics and cranks, a justification for a “Dictatorship of Virtue,” the basis of “Totalitarian Democracy,” the original form of “Terrorism” Benjamin Constant on Rousseau’s political philosophy: I shall perhaps at some point examine the system of the most illustrious of these philosophers, of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and I shall show that, by transposing into our modern age an extent of social power, of collective sovereignty, which belonged to other centuries, this sublime genius, animated by the purest love of liberty, has nevertheless furnished deadly pretexts for more than one kind of tyranny. [Rousseau should be] regarded as the representative of the system which, according to the maxims of ancient liberty, demands that the citizens should be entirely subjected in order for the nation to be sovereign, and that the individual should be enslaved for the people to be free. Sparta, which combined republican forms with the same enslavement of individuals, aroused in the spirit of that philosopher an even more vivid enthusiasm. That vast monastic barracks to him seemed the ideal of a perfect republic. He had a profound contempt for Athens, and would gladly have said of this nation, the first of Greece, what an academician and great nobleman said of the French Academy: What an appalling despotism! Everyone does what he likes there. John Stuart Mill b. 1806 d. 1873 1809-1820 Education begins at age 3, with Aesop and Xenophon By age 14, has completed study of most of the Greek and Latin classics – in their original languages 1821 Completes reading of Bentham; becomes advocate of Utilitarianism 1823 Arrested for distributing birth control literature 1826 Mental breakdown; begins rethinking principles of Utilitarianism 1830 Meets Harriet Taylor [1832 Bentham dies] [1836 James Mill dies] 1851 Marries Harriet Taylor 1835 Reviews and endorses Tocqueville’s Democracy in America 1859 Publishes On Liberty 1861 Publishes Utilitarianism and Considerations on Representative Government 1869 Publishes (with Harriet Taylor) Subjection of Women Liberalism as a political tradition “Liberalism” is the dominant ideology in English speaking nations “Liberty” is individual freedom to act without interference from others; a “modern” form of liberty -- Originally an argument against monarchical and aristocratic privilege and authority Some notable achievements of liberalism: Freedom of religion Political and civil rights (for propertied individuals) Economic freedom (capitalism) -- Today an argument for individual opportunity for self-realization The problem for liberalism: What is required for individual self-realization? Liberalism’s two schools “Protective” liberalism “Developmental” liberalism John Locke John Stuart Mill “conservatives” in liberal polities (economic liberals, moral conservatives) “liberals” in liberal polities (moral liberals, economic conservatives) Libertarianism Something of a child prodigy, he learned to read as a toddler and began the study of Latin at age three. At 12 he was sent to Oxford, and was admitted to the bar at age 16. A prolific linguist, he eventually became fluent in 7 different languages: English, French, Spanish, German, Russian, Latin, and Greek, and was familiar with a half dozen more. He became disillusioned with the law, and when he was made financially independent after the death of his father, he dedicated himself to progressive political movements, including prison reform, poor relief, the codification of international law, the decriminalization of homosexuality, and animal welfare. One of the most influential founders of University College in London, which was one of the first colleges open to all races, sexes, and classes. A bit of an eccentric, for ten years before his death he carried around the glass eyes he planned to have inserted in his body after death. He fancied himself an amateur scientist, and when he died, he was embalmed with a fluid of his own invention. He gave all of his estate to UCL, on the condition that his body be kept on display at the College, and was present at all meetings of the College governing board. Unfortunately, his scientific skills left something to be desired. In a short time, the body shriveled up, and the head fell off. A wax effigy replaced the decomposed body, and the head was placed at the foot of the effigy. Undergraduates being what they are, the head frequently went missing. Once it was found in a storage locker at Aberdeen Station, and it occasional served as a ball for impromptu soccer matches on the college lawn. Eventually the head was boxed and stored away from the scheming plans of pranksters. The effigy, called the "auto-icon" can still be viewed at UCL. The minutes of the College governing board most often read "Mister X present but not voting," although it is said he does occasionally vote, always for the motion on the floor, whenever there is a tie. HINTS: (3) Designer of the innovative prison called the Panopticon (2) He coined a number of neologisms that have become part of common idiom. "Maximize" and "Minimize" being the most familiar (1) Founder of the movement known as Utilitarianism Jeremy Bentham and Utilitarianism Jeremy Bentham and Utilitarianism The goals of society and government: “The Greatest Good for the Greatest Number” The question for reformers: How can society and government be fitted to human nature? Human nature Maximize pleasure, minimize pain The problem for reformers: Variety of preferences and standards “Quantity of pleasure being equal, pushpin is as good as poetry” Solution: Measurement of pleasure and pain: “The felicific calculus” Preferences measured by market mechanisms. “Money is the instrument of measuring the quantity of pain and pleasure” “Each portion of wealth has a corresponding portion of happiness” Government goals 1. Provide subsistence 2. Produce abundance 3. Favor equality 4. Maintain security Do nothing; fear of starvation will work Do nothing; individuals will always want more Equality must yield, or incentives disappear John Stuart Mill and the Problem of Human Felicity The Goal of human life: individual happiness The Means of individual happiness: individual liberty The Political Principle of liberty: individual self-sovereignty The Questions We Must Ask What constitutes Individual Happiness? Are there limits to Liberty? What is required for Self-sovereignty? The only useful answers to these questions must be given in terms that bear on the problems of self-development in social relations Utilitarianism is the social theory of human felicity Utilitarianism (the social theory of human felicity) The purpose of social theory: What is useful for human happiness The goal of society and government (the principle of utilitarianism): The Greatest Happiness for the Greatest Number of Individuals The first and fundamental question: What is happiness? Definitional basis Hedonism vs. Excellence Conditions “Internal” (intellectual) “External” (material) Low High High High Considerations: What is the relationship of internal and external conditions? What are the individual and social implications of these ideals of happiness? Mill’s conclusion: Utility (the greatest happiness) requires progress, and progress requires Competence On Liberty Utility requires progress, and progress requires competence Liberty is the means of self-development for happiness; liberty both protects and develops competence Obstacles to competence Internal External Developing Ignorance Deprivation Protecting Infirmity Tyranny Historical limits of competence: Intellectual and material wealth Greatest danger to competence and individuality in appropriate conditions: Tyranny of the Majority The principle of liberty: freedom in all “self-regarding acts”; social/governmental regulation of “other-regarding acts” ONLY Liberty protects competence by preventing majority tyranny; liberty develops competence by encouraging individual self-development Spheres of liberty: Thought and expression (for truth) Tastes and pursuits (for individuality and diversity) Association (institutional forms for thought, expression, tastes and pursuits) Further considerations on development (or, why government should be limited): Overactive government is inefficient and undermines self-reliance Governments have limited capacity; individuals know their own interests Paternalism stunts development; individual initiative encourages self-development Monopolization stunts innovation; individual independence encourages creativity Mill on Representative Government Review: The prerequisites of progress Intellectual Material Capacity requires Development and requires Protection Productive societies requires requires requires Democracy Meritocracy Bureaucracy w/ expertise REPRESENTATIVE GOVERNMENT Limitations: insubordination, passivity, localism Conditions of success: Acceptance, action, and capacity Underdevelopment Particularity Threats to success Negative Positive Insufficient power Incompetence Remedies: Political participation and effective bureaucracy Means: education by example, experience, and public schooling Further considerations: enfranchisement and electoral influence