* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download notes 2nd midterm

Present value wikipedia , lookup

Securitization wikipedia , lookup

Syndicated loan wikipedia , lookup

Shadow banking system wikipedia , lookup

Monetary policy wikipedia , lookup

Interest rate ceiling wikipedia , lookup

Quantitative easing wikipedia , lookup

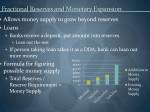

Fractional-reserve banking wikipedia , lookup

The Bank Balance Sheet Banks are a financial intermediary, taking the funds of depositors and turning into loans in their primary business. This process is one of asset transformation: the assets of a persons savings deposit are converted to a home loan, which is a bank assets, and the bank creates liabilities in the process. We will see this with a look at a banks balance sheet. A summary of almost 8000 commercial bank balance sheets for August 2004 is on page 288. A bank's balance sheet is simply a list of a bank's assets and liabilities where total assets = total liabilities + capital. Assets Assets are a bank's uses of funds. Reserves. All banks must hold some funds to satisfy the withdrawals of their depositors (known as vault cash), and they are also required to hold some funds in deposits at the Fed. The some of these holdings are the bank's reserves. Some of the reserves are required reserves that much be held by law. This requirement is set by the Fed as a percentage of deposits and is called the required reserve ratio. The remaining are excess reserves held to satisfy depositor withdrawals. Cash items in process of collection include funds being transferred from one bank to another, mostly due to check writing and depositing between different banks. Banks often have deposits at other larger banks for check clearing and exchanging foreign currency. Securities. Banks hold securities as a source of income (and profit). Bank's security holding are only debt securities as they are not allowed to hold stock. Banks hold a large amount of U.S. government debt due to its high liquidity and low risk. This type of debt can be sold quickly to raise cash, so they act assecondary reserves. Banks also hold municipal debt for its tax advantages and to gain the business of those municipalities. Loans. Over 60% of a commercial banks assets are loans. Categories include commercial lending, real estate lending, consumer loans, and interbank loans. Specific institutions will often specialize in a category of lending. Loans are significantly less liquid than securities and often have a higher default risk. Liabilities Liabilities are a bank's sources of funds. Over 60% of the funds for commercial banks come from deposits. Checkable deposits include basic checking accounts that earn no interest, along with other interest-bearing checking accounts (NOW accounts and money market accounts). The low or zero interest on these accounts make them a cheap source of funds, but they are also expensive for banks to service as well. These types of deposits have declined proportionally as a bank liability as people have turned to other alternatives from nondepository institutions, namely money market mutual funds. Nontransaction deposits are the most important source of bank funds. The pay higher interest but have no check-writing privileges. Savings deposits, small time deposits and large time deposits are all in this category. In addition to deposits, banks also obtain funds from borrowing. Borrowed funds include Discount loans from the Federal Reserve system Federal funds, which are loans from other banks Repos, which are asset repurchase agreements from corporations Eurodollar loans from foreign banks Commercial paper issued by the bank holding company. Bank Capital Bank capital refers to the bank's net worth or assets minus liabilities. This capital provides a safety net in case some of the banks assets fall in value, so the bank can still meet it obligations to the depositors and creditors. One important component of bank capital is loan loss reserves, specifically set aside to cover defaulted loans. Note that in the bank balance sheet on page 288, bank capital is $700 billion on $7.2 trillion of liabilities. This is a leverage of 10 to 1--a bank borrows $10 for every $1 in capital. This degree of leverage is far greater than U.S. households or even other nonfinancial businesses. As we will see in the next chapters, government guarantees enable banks to get away with this high degree of leverage and the risk it entails. Banks also must make decisions about capital. Capital provides protection for the bank from bad loans or securities. Without it, any loss in asset value could lead to insolvency for the bank. However, lower bank capital will increase the return to the banks shareholders (the ROE, equation 3, 296). So the bank faces a tradeoff between safety and the returns to the bank's owners. Because of this conflict, federal regulators set minimum capital requirements for banks, as a percentage of risk-adjusted assets. Bank Risks The leverage in the banking industry, along with the unique deposit-taking features of its business, expose the industry to a variety of risks. Liquidity Risk But how does a bank decide how much to lend and how much to keep as excess reserves? This is the key issue in liquidity management, where bank managers must decide the amount of liquidity necessary to deal with deposit outflows. The tradeoff here is this: Reserves earn no interest, so too much excess reserves will drag down profits. However, if the bank holds insufficient cash to meet deposit outflows, then it must raise additional cash by borrowing from other banks in the federal funds market, incurring borrowing costs borrowing from the Fed, which could increase regulatory scrutiny as well as incur borrowing costs selling securities, which incurs trading costs call in some existing loans and risk alienating bank loan customers or sell some existing loans, typically at a steep discount. All of these options are costly in some way. So banks will hold some excess reserves to reduce the probability of having to raise additional cash quickly. The amount of excess reserves will depend on the costs of raising cash as well as the expected deposit outflows. This will also affect the amount of secondary reserves the bank chooses to hold. In managing the asset side of the balance sheet a bank has several goals: maximize returns (and profits) minimize risk adequate liquidity regulatory compliance Again, these goals involve tradeoffs. If a bank is too conservative with respect to risk and liquidity (choosing assets with only high liquidity and low risk), then asset returns may be too low to return a profit. Banks that take on too much risk and incur loan defaults could end up insolvent, with the value of assets too low to satisfy all liabilities. Liability management has taken on more importance in the last 30 years as banks have facing increasing competition from other financial institutions with new financial instruments and as financial markets opened up new alternatives for banks to raise funds. Large banks, known as money center banks, raise funds through avenues other than deposits, including commercial paper markets, CD markets, and the federal funds market. Credit Risk The previous discussions about asset and capital management highlight the importance of managing credit risk (or default risk) for banks. As loans are the primary asset for commercial banks, the problems of adverse selection and moral hazard come into play. A bank must deal with these problems in order to minimize its credit risk. Recall from chapter 11 that adverse selection occurs BEFORE the loan is made, in that individuals that engage in risky behavior or more likely to want to borrow money in the first place. Moral hazard occurs AFTER the loan as an individual may "blow" the money and not be able to repay it. Also described in chapter 11 are the variety of ways banks deal with these problems: screening, collateral, monitoring to name a few. One key to risk reduction is diversification. By holding the debt and loans of many different borrowers, a bank can reduce default risk without sacrificing too much return. Too often banks have specialized in lend to one industry, like agriculture or oil, and have suffered losses when those industries hit hard times. Interest Rate Risk Both a bank' assets and liabilities are sensitive to changes in market interest rates. For assets, changes in interest rates affects the VALUE of assets, but also the interest INCOME they generate in different ways. Long-term assets, such as long-term securities and loans generate income that is not sensitive to interest rate changes (although their VALUE is very sensitive). However short-term assets such as federal funds, variable-rate loans, or short-term loans and securities generate income that fluctuates with market interest rates. On the liability side, the cost of acquiring funds (the interest paid by banks) goes up with interest rates, especially for money market accounts and shortterm CDs. The cost is more stable for long-term CDs, checking deposits, and savings deposits. So when interest rates rise, the cost of liabilities goes up, but the income from assets go up as well. The total effect on bank profits will depend on whether the rate-sensitive assets outnumber the rate-sensitive liabilities. In most cases, banks have many more rate-sensitive liabilities than assets, so rising interest rates may result in falling profits. This is because banks typically borrow short-term and lend long-term, a function known as maturity intermediation. As interest rates have become more volatile in the past 30 years, banks have taken measure to manage their interest rate risk using derivative securities, which we discussed in Chapter 9. Trading Risk Risk management has become an essential part of overall bank management. However managing these risks involves the trading of derivative assets that introduce new risks. Traders working on behalf of banks are able to bet large sums of money without being responsible for covering losses. This introduces what economists refer to as the principalagent problem. The principle (the bank) and the agent (the trader) may have different objectives so that the trader does not always operate in the bank's best interest. An example of the disastrous effects of rouge traders is discussed on page 308. Other Bank Activities Banks increasingly generate revenue through activities not on the balance sheet. These activities are a growing source of bank profitability. Loan sales have risen with the growth of a secondary loan market. Instead of remaining on the balance sheet until paid, banks sell loans or just the right to the loan payments to third parties. If these loans carry higher interest rates than the current market, they will sell at a premium. If the loans carry lower interest rates, they will sell at a discount. Either way, a loan sale will free up funds for the bank to make additional loans. Fee income has increased in importance in its contribution to bank profits. These include ATM fees, account service fees, fees for servicing loans after their sale, and fees for more specializing lending services. Banks also receive fees for guaranteeing securities against default, acting as a co-signer with a debt issuer. As banks increasingly face competition from other finance companies for the loan market, this has interest-rate margins, and thus profits down. Fee income has helped increase profitability in the 1990s. The Central Bank Balance Sheet and the Money Supply Process In this chapter we begin to look at the mechanics of how the Federal Reserve affects the money supply. The Feds track record as stabilizer is mixed, as noted in the beginning of this chapter. The Fed's success in maintaining the stability of financial markets in the aftermath of 9/11 is a remarkable success and a stark contrast to its failure to stem the banking crises of the Great Depression. Though the Federal Reserve is the most important player in the money supply process, there are four players in total: 1. The Federal Reserve 2. Depository institutions--including commercial banks, savings and loans, credit unions 3. Depositors holding deposits in these institutions. 4. Borrowers obtaining loans from these institutions. The behavior of all parties determine the money supply and the size of changes in the money supply. The Fed's Balance Sheet The balance sheet is summarized on page 428 of your textbook, in table 17.1. We just go over top items here: Assets 1. U.S. government securities dominate the asset side of the Fed balance sheet. Holding this large inventory is essential for open market operations. 2. Loans consist of discount loans, loans by the Fed to other banks and the float, balances of checks in the process of clearing from different banks around the country. 3. Foreign exchange reserves are the Fed's holdings of currency of other countries, usually in the form of foreign government bonds. This reserve is essential for foreign exchange interventions discussed in chapter 10. The first two items earn interest and make the Fed self-funding. They are also key to the Fed's control of the money supply. Liabilities 1. Currency in circulation The Federal Reserve issues all U.S. currency (printed by the U.S. Treasury Bureau of Engraving, but issued by the Fed.) The top of all U.S. currency reads "Federal Reserve Note" U.S. currency in circulation to the nonbank public is a liability for the Fed, but the Fed just exchanges them for additional notes. It is their wide acceptance as a medium of exchange that gives them value. 2. Government accounts The Treasury needs a bank account just like we do to issue checks and tranfer funds. 3. Reserves. All commerical banks must keep reserves in an account at the Fed. Reserves consist of required reserves and excess reserves. The required reserve ratio determines the fraction of deposits that banks are required to hold as reserves. Any extra amount held are excess reserves. The liabilities in the Fed balance sheet basically make up what is known as the monetary base or high-powered money. Basically, monetary base = currency + reserves = C + R The monetary base is an important measure of the money supply since a $1 increase in the monetary base will lead to an increase in the money supply of more than $1. Control of the Monetary Base The Federal Reserve is able to control the monetary base through open market operations and through discount loans to banks Open Market Operations On page 434, your textbook uses T-accounts to show you how open market operations affect the monetary base. I will just explain the process here. When the Fed makes an open market purchase, they buy securities from banks or the public. If purchased from a bank, the banks receives money from the Fed in return for the securities. So bank reserves increase by the amount of the purchase. If purchased from the public and the public deposits proceeds in a checking account, bank reserves also increase by the amount of the purchase. If purchased from the public and the public keeps the proceeds as cash, currency increases by the amount of the purchase With each possibility outlined above, either reserves increase or currency increases. Since the monetary base is the sum of reserves and currency, we can conclude the following: When the Fed conducts an open market purchase, the monetary base increases by the amount of the purchase. In an open market sale, when the Fed sells securities to banks or the public, the monetary base will fall by the amount of the sale. Discount Loans When the Fed makes a discount loan to a bank, it simply credits that bank's reserve account kept at the Fed. So with a discount loan, reserves increase, so the monetary base increases. So either an open market purchase or discount loans by the Fed will increase the monetary base by increasing either reserves or currency. Deposit Creation Now, when the Fed does increase reserves by $1, deposits in the banking system will increase by more than $1. This is known as multiple deposit creation. On pages 440-45 we see a simple case of this in action. Start on page 440. When the Fed buys securities from First Bank, then First national has $100,000 LESS in securities and $100,000 MORE in reserves. These reserves are excess reserves, so the bank can then lend them out, creating a $100,000 loan. On page 442, the borrower of the $100,000 loan from First National takes the loan and deposits it in Send Bank. So Second Bank has $100,000 more in checking deposits and $100,000 more in reserves. Suppose the required reserve ratio is 10%. Second Bank must keep $10,000 of the reserves and is free to lend out $90,000. On page 443, the borrower of the $90,000 loan from Second Bank takes the loan and deposits it in Third Bank. So Third Bank has $90,000 more in checking deposits and $90,000 more in reserves. With the reserve requirement of 10%, Third Bank must keep $9,000 of the reserves and is free to lend out $81,000. This process could keep going, but let's see where we are now. Due to the $100,000 open market purchase, checking deposits have increased by $100,000 + $90,000 + $81,000 = $271,000. The Fed, through borrowers, depositors, and the banking systems have created money. This process also works in reverse, causing multiple deposit contraction. The Simple Money Multiplier If this process kept going, as shown in Table 17.17, page 444, more deposits would be created. How much in total? We can calculate this with the simple deposit multiplier, which is simply the inverse of the reserve requirement: change in deposits = change in reserves x (1/reserve requirement) In our example, change in deposits = $100,000 x (1/.10) = $1,000,000 So with a reserve requirement of 10%, a $100,000 increase in reserves will create a $1 million increase in deposits. You may have noticed by now that this model is a bit simplistic. In particular, it leaves out two possibilities: 1. If borrowers take some of their loans as cash rather than deposit the entire amount, then the simple money multiplier overstates deposit creation. 2. If banks choose to hold some of their excess reserves instead of lending out the entire amount, then the simple money multiplier overstates deposit creation. Let's look at a more complicated version of the money multiplier that takes into account the cash and excess reserves preferences of banks and the public. The Monetary Base and the Money Supply Your textbook spends a couple of pages deriving this money multiplier, but we will instead focus on the movement of the given multiplier. So we seek to define a multiplier that tells us how changes in the monetary base affect the money supply: M = m x MB, where M is the money supply, m is the money multiplier, and MB is the monetary base. We derive the following money multiplier: Where r is the required reserve ratio, C/D is the ratio of currency to checkable deposits and ER/D is the ratio of excess reserves to checkable deposits. Plugging in some numbers, we can calculate the multiplier: = .10 C = $400 billion D = $800 billion ER = $.8 billion so the money supply M = C + D = $1200 billion The multiplier = So any changes in , (C/D), (ER/D) change the multiplier and change the affect of changes in the monetary base on the money supply, IN THEORY By looking at the multiplier or by using our intuition, we can determine the direction of these changes. With a higher reserve requirement, banks will have fewer excess reserves to lend out, and the amount of deposit creation will be smaller. Also, note that r is in the denominator of the money multiplier, so higher values for r mean a smaller money multiplier. So the higher the reserve requirement, the smaller the money multiplier. As depositors hold more currency, this currency does not expand the way that deposits do. So the higher the currency ratio, the smaller the money multiplier. When the ratio of excess reserves to deposits rises, banks are holding more excess reserve relative to deposits, which leaves less available for multiple deposit expansion. So as the excess reserves ratio rises, the money multiplier falls. We might expect both C/D and ER/D to fall as interest rates rise, since the opportunity cost of holding cash and excess reserves becomes greater. This changes the money multiplier and money supply. However, in the U.S. and most modern economies the money multiplier is too variable and the Fed is unable to exercise a lot of control over the money supply through altering the monetary base through open market operations. In modern monetary policy, the Fed is more concerning about the long run growth trends of money and the implications for inflation. Monetary Policy: Using Interest Rates to Stabilize the Domestic Economy Now that we've studied the money supply process, we take a closer look at how the Fed impacts the domestic economy. The Fed has three tools at it's disposal to impact the money supply: (1) open market operations (the federal funds rate target), (2) discount lending, (3) the reserve requirement. In this chapter we see how each tool impacts the federal funds market and evaluate its usefulness. The Market for Reserves and the Federal Funds Rate Recall that the federal funds rate is the short term interest rate for the interbank lending market where banks lend reserves to each other. The Fed conducts monetary policy primarily through affecting this market, which in turn impacts other debt markets and the economy. The figure below shows the market for reserves, which determines the equilibrium federal funds rate: Note that the demand for reserves is downward sloping with respect to the federal funds rate. This is because the federal funds rate is the opportunity cost for a bank holding excess reserves, since the bank could lend out those reserves at the federal funds rate. So the higher the federal funds rate, the higher the opportunity cost of holding excess reserves, so the quantity of excess reserves (and reserves) will be lower. The supply curve is upward sloping because as the federal funds rates rises, banks will provide more reserves for other banks to borrow. How do the three tools of monetary policy impact this market? We have seen in chapter 17 how an open market purchases increases reserves in the banking system. So an open market purchase increases the supply of reserves, causing the federal funds rate to fall. An open market sale causes the federal funds rate to rise. We have seen in chapter 17 how increases in discount loans will increase reserves. So a lower discount rate will encourage bank borrowing, increasing the supply of reserves and decreasing the federal funds rate. With an increase in the required reserve ratio, banks must hold more reserves. A higher reserve requirement increases the demand for reserves and causes the federal funds rate to rise. Open Market Operations Open market operations are the most important tool of monetary policy. An open market purchase increases the monetary base and the money supply, lowering short-term interest rates. In theory the Fed could conduct open market operations with any type of debt security. In reality it uses Treasury securities because this market is large and liquid, so it can absorb large transactions. The FOMC votes on open market operations by voting on a federal funds rate target to be acheived through open market operations. The actual buying and selling is left to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (which is why the FRBNY president always has a vote on the FOMC). Every trading day, the FRBNY open market operations staff surveys conditions in financial markets to determine what type and how much of open market operations are need. They then line up potential buyers and sellers of Treasury securities by getting price quotes from large dealers in securities known as primary dealers. There are about 30 primary dealers. (FYI: Cantor Fitzgerald, a bond trading firm that lost 658 people in the WTC attack in September, did almost 25% of the trading volume in Treasury securities. They have since recovered that market share.) Trades are executed throughout the day, while watching for the desired impact in the federal funds market. Now the FOMC can set a target and the FRBNY buys and sells to keep the equilibrium federal funds rate as close to the target as possible. The difference between the target and actuall federal funds rate is shown in figure 18.2, page 464. OMO are the primary tool of monetary policy. They are flexible, so the Fed and change the federal funds rate by a little or a lot. They are quick and precises, with same day impact on the interbank lending market, with other short-term interest rates following quickly. They are reversible. If the Fed buys too many securities, they can turn around and sell some of them. Discount Lending Discount loans increase the monetary base and money supply. Each Federal Reserve district bank has a discount window where loans are made. They affect the volume of discount loans by setting the discount rate and by deciding when to make loans. Discount loans are made to banks for very short-term liqudity problems at the primary discount rate = federal funds rate + 100 basis points. They are also given to banks in regions with seasonal fluctuations in reserves (such as agricultural areas), and finally to banks in serious trouble at the secondary discount rate = federal funds rate + 50 basis points. However, banks have an incentive not to come to the discount window too often, since this would invite additional scutiny from regulators concerned about the bank's liquidity management. Beyond their ability to affect the monetary base, discount loans get to the original purpose of the Fed: To be a lender of last resort to banks in trouble in order to prevent larger bank and financial panics. The Fed, frankly, messed up this role during the Great Depression, but have done well in the post-WWII period in its role as lender of last resort. Even with the FDIC to insure deposits, the Fed still needs to be willing to provide liquidity to protect large depositors and to keep the FDIC from going bankrupt in the case of too many bank failures. Despite the importance of discount loans for financial market stability, they are not an ideal tool for changing the money supply: 1. Changes in the discount rate may be taken as a signal of monetary policy (an announcement effect) when the Fed is only trying to keep up with market interest rates. The fluctuating spread between the federal funds rate and discount rate will cause the volume of discount loans and the money supply to fluctuate, actually making it harder to control the money supply. 2. Discount loans are not completely under Fed control. They depend on bank behavior as well. 3. Discount rate changes are not easily reversible, since the rates on previous loans cannot be changed. Reserve Requirements The Federal Reserve Board of Governors sets the reserve requirements for depository institutions. Higher reserve requirements reduce the money multiplier and the money supply, causing short-term interest rates to rise. Required reserves on checkable deposits are 3% up to $44.3 million and 10% on the amount over $44.3 million. Changing the reserve requirement is certainly effective. In fact it is a very powerful tool. This is actually a disadvantage. The Fed usually wants to make small adjustments to the money supply, and that is not possible with the reserve requirment. As one of my economics professors once said, "it's like using a nuclear warhead when just a fly swatter will do." Also, practically speaking, the reserve requirement is expensive to change: Banks must change all types of liquidity and asset management strategies. Frequent changes in the reserve requirement would force banks to hold a large cushion of excess reserves to deal with the resulting uncertainty, cutting into their profits. While reserves were originally required to ensure the soundness of the banking system in meeting depositor withdrawals, today the reserves deposited at the Fed help the Fed maintain the federal funds rate target. The Goals of Monetary Policy There are 4 basic goals of monetary policy , which are really desirable goals we want to see for the economy: High Employment (Low unemployment). The federal government is required under laws passed in 1946 and 1978 to promote high employment consistent with price stability. It is clear why high unemployment would be bad: unused resources mean lost output and there are huge personal/social costs as well. But what level of unemployment is acceptable? As we learned in Principles of Macroeconomics the goal for unemployment is NOT zero. There will always be frictional and structural unemployment. The goal for unemployment is the natural rate of unemployment, estimated to be somewhere between 4 and 5%. The current unemployment rate is around 5.1%. FYI: The unemployment rate for the Syracuse area is currently at 4%, lower than the NYS 4.6%. Economic Growth. This goal is closely related to the goal of high employment since strong economic growth leads to job creation and high employment while stagnant or falling economic growth means layoffs. Economic growth (the % change in real GDP) in the U.S. averages about 3%, although the averages for growth in the 1970s and 1980s were lower, but have rebounded in the 1990s. In 2006 real GDP rose about 2.7%. Price Stability (Low inflation). Today this is view as the most important goal of monetary policy, not only by the Fed but by the European central banks as well. At high levels, inflation creates uncertainty, lower investments, and lower economic growth. How high is too high? In the U.S. currently, the Fed wants an inflation rate of about 2%, with higher than 4% being unacceptable. Inflation is a concern in 2007, given rising energy and food prices. In 2006 prices rose about 2.5% as measured by the CPI. Financial Market Stability. This category includes the stability of financial institutions, interest rates, and foreign exchange rates. Interest rate stability creates a more favorable investment climate and promotes economic growth. Stepping in to avoid financial crises also avoids the extreme recessions that can follow such crises. A stable exchange rate promotes international trade. This last goal often requires international cooperation with many central banks around the world. Linking Tools to Objectives To function as an effective instrument a tool must be easily observable by all controllable by the Fed predictably related to the objectives of monetary policy such as economic growth, low inflation, low unemployment, etc. These criteria rule out discount lending and reserve requirement, and leave open market operations. Why? 1. The Fed has complete control over open market operations. Not true with discount loans, where the banks decide to borrow or not. 2. Open market operations are flexible. They can do a little or a lot, depending on the size of the change desired. 3. Open market operations are easily reversible. If the initial purchase is too large, then the Fed just has to sell some. 4. Open market operations are quick. Trades and their impact appear almost immediately during the trading day. To summarize, all 3 tools at the Fed's disposal are capable of changing the money supply and interest rates, but only one tool, open market operations, is of practical use for conducting monetary policy. We will see how this tool is used to achieve economic goals The Fed has these ultimate goals, but they only have direct control over a open market operations. Unfortunately it can take over a year for the tools to eventually impact the economic goals. How does the Fed gauge its progress? Through the use of targets. These targets are other variables related to both the tools and the goals of monetary policy. By looking at these variables, the Fed knows if it is on the right track. The process looks like this: First, the operating targets are variables closely related to the tools, and respond immediately to changes in the tools. Possible operating targets include reserves, the federal funds rate, or a Tbill rate. Currently the FOMC targets the federal funds rate. The intermediate targets are variables affected by the operating target, but are closely associated with the goals. Possibilities includes the money aggregates (M1, M2, M3) or other short-term and long-term interest rates in the economy. Given the breakdown between monetary targets and the economy is recent decades, intermediate targets are not as important as they used to be. So for example, the Fed may want a 5% growth rate for nominal GDP. To do this, they believe they need 4% growth in M2, which will be accomplished with 3% growth in the monetary base. Then, the Fed conducts open market purchases to increase the monetary base by 3% (the operating target), which is measures fairly quickly. Over the next few months it follows changes in M2 to hit a growth rate of 4%. If M2 growth is too low, the Fed will conduct more open market purchases. If the growth rate is too high the Fed will reverse and conduct open market sales. However, the FOMC MUST make a choice between monetary and interest rates targets: they cannot simultaneously target both! Let's see why. Suppose the Fed wants to target the money supply M*. As money demand fluctuates, the equilibrium interest rate will change. This is because the Fed is committed to M* as a target so it does not shift the MS curve when MD shifts. The result is an interest rates that fluctuates with money demand: Suppose instead the Fed wants to target an interest rate i*. As money demand fluctuates, the equilibrium interest rate will rise above or fall below i*, the target. To prevent this, the Fed must increase or decrease the money supply to compensate, keep the equilibrium interest rate at i*. The result is that the money supply fluctuates when money demand fluctuates as the Fed pursues its interest rate target. If the Fed targets the money supply, then it loses control of interest rates. If the Fed targets interest rates, then it loses control of the money supply. The Taylor Rule The federal funds rate is clearly a popular target for monetary policy. How should this target be chosen? The Taylor Ruleis currently a popular policy rule created by John Taylor of Stanford University. The Taylor rule is an equation the says the target federal funds rate should be based on the current inflation rate, the real federal funds rate (a long-run equilibrium rate), the gap between real GDP and full employment GDP, and the gap between actual inflation and the inflation target. FF rate target = 2.5 + current inflation + (1/2)(current-target inflation) + (1/2)(current - potential GDP) So when inflation rises above its target level, the federal funds rate target should rise. When output falls below its potential level then the federal funds rate target will be lower. So the rule responds to economic conditions, including both prices and output. This relationship makes the federal fund rate target based on concerns about both price stability and the business cycle.