* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 36. Part One of Reconstruction

Economy of the Confederate States of America wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Lewis's Farm wikipedia , lookup

Anaconda Plan wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Namozine Church wikipedia , lookup

East Tennessee bridge burnings wikipedia , lookup

South Carolina in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Virginia in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Fort Pillow wikipedia , lookup

Opposition to the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution wikipedia , lookup

Alabama in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Confederate privateer wikipedia , lookup

Conclusion of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Jubal Early wikipedia , lookup

Georgia in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

United States presidential election, 1860 wikipedia , lookup

Lost Cause of the Confederacy wikipedia , lookup

Border states (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Carpetbagger wikipedia , lookup

Mississippi in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution wikipedia , lookup

Union (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Tennessee in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Issues of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Commemoration of the American Civil War on postage stamps wikipedia , lookup

United Kingdom and the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Hampton Roads Conference wikipedia , lookup

Military history of African Americans in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

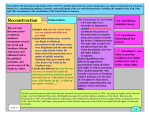

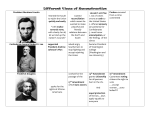

Radical Republican wikipedia , lookup

Part One of Reconstruction The last weapons fired in the conflict between the North and the South were not rifles or cannon but words. Just as a war of words preceded the Civil War, the last volleys were in the form of three amendments to the Constitution designed to punish the South. The 13th Amendment was, in December of 1865, the first amendment to the Constitution since 1804 so it is radical even in its timing. It also launched Reconstruction, one of the most complex and controversial periods in US history. The term reconstruction does not merely imply rebuilding burned cities or torn-up railroads. The period historians call Reconstruction is when the country tried to figure out how to go forward as one nation in the aftermath of the Civil War. Several crucial questions demanded answers. Should the Rebels be punished? How were the slaves to be kept free? What rights did freedmen have? When, and how, and under what conditions should the seceded states be readmitted to the Union? Will the readmitted states be permitted to vote in national elections? Would they be allowed representation in the Congress? Essentially, would the former Confederate states ever be allowed to be equal members of the United States again? The reason Lincoln’s death by assassination was a calamity for the South was that his plan for Reconstruction was the most lenient of the three that would be proposed. Had Lincoln lived, he would have served out his second term as President and guided the process. While there were many detractors opposed to Lincoln’s ideas, he had stood alone on more than one issue already. His entire Cabinet had feared the issuing of the Emancipation Proclamation, but it proved to be one of Lincoln’s most significant contributions to US history and laid the groundwork for the 13th Amendment which abolished slavery. Lincoln’s plan was known as the 10% Plan because he suggested that when 10% of a state’s population disavowed the Confederacy and supported a pro-Union government, the rebels of that state would be given amnesty. John Wilkes Booth removed any possibility for a benevolent federal government’s forgiveness. Lincoln’s second Vice President was a unionist Tennesseean named Andrew Johnson, the only Southern US Senator not to leave the US Congress upon the secession of his state. As President, Johnson’s plan for Reconstruction was just, but not harsh. He said Southern whites should initiate new state governments while he appointed new state governors. These hand-picked governors would call state conventions to form new constitutions with three requirements. Each reconstructed state must adopt the 13th Amendment, repeal their acts of secession, and cancel their war debts. These “hoops” through which Johnson wanted the states to jump were intended to make the people of the South regret that they had ever supported the Confederacy, especially if they had purchased war bonds. By 1866, all the eleven seceded states were on their way back, but you can probably gather that Johnson was ultimately unsuccessful by the fact that Mississippi did not adopt the 13th Amendment until your lifetime. Johnson recommended that the states he had reconstructed send Congressman back to Washington, DC. Congress, however, had grown jealous of Executive power during Lincoln’s presidency and tacked on the 14th Amendment as another hoop. The 14th Amendment, among other things, said that freed slaves were citizens, a radical departure from the ante bellum Supreme Court. The South refused ratification and a third plan for Reconstruction was launched by the Radical Republicans who wanted to punish the South for the war. The 13th and 14th Amendments had already earned them their radical label, but they became harsher and pushed for black male suffrage with the 15th Amendment. The Reconstruction amendments, therefore, are the 13th, 14th, and 15th. Roughly, they freed slaves, made freedmen citizens, and gave black males the right to vote. At no other time for another century could they have been possible. Only when former Confederate/Democrats could still not vote and when radicals in the Republican Party had taken control in the wake of Lincoln’s assassination were they accomplished. Together they were a punitive peace that made the South’s way of life Gone with the Wind. Only Tennessee escaped the righteous indignation of the Radical Republicans partly because it was Johnson’s home state but mostly because it had been conquered early in the war. Tennessee was Reconstructed (back in the Union) by 1866. Most other states had to wait until 1871 when they submitted to equality-based constitutions forced on them by an occupying Union Army’s protection of black voters. The South was even divided up into five military districts and placed under martial law, and three states still did not submit to the repressive measures of the Radical Republicans until 1877 when Reconstruction was considered over. On the brink of being dissolved, the federal government had asserted sweeping powers that totally reorganized society in ways that some Southerners rue even to this day. Those stubborn holdouts, however, should contemplate the frightening prospect that Reconstruction could have been much worse. There are at least three groups with motives to make Reconstruction harsher, more violent, and more repressive. If any one of three possible scenarios had occurred the process of Reconstruction could have taken significantly longer and crippled our nation even to the point of keeping us on the sidelines in the two World Wars of the Twentieth Century, which is to say, the “new birth of freedom” of which Lincoln spoke at Gettysburg could have been snuffed out. For once in A. P. US history I will deal for a time with “What if?” None of these scenarios happened, but to truly understand Reconstruction we should briefly imagine why they might have happened and what would have been the consequences for all Americans if they did. First, since the North had lost 360,000 men and would eventually pay $10 billion to cover the cost of putting down the rebellion, Reconstruction could have been worse. Beyond these costs in lives and treasure, there was the discovery after the war of the atrocities of Andersonville, Georgia, where a Confederacy that could barely afford to feed its own soldiers kept prisoners of war in conditions of extreme exposure and deprivation. Twelve thousand of the fifty thousand prisoners who went to Andersonville died, a death toll of almost 1 in 4. To the outrage of other segments of the Northern population, Nathan Bedford Forrest was said to have ordered the beating, shooting, and burning of black soldiers he had captured in Tennessee. Both Frank and Jesse James got their start as outlaws by committing other atrocities while “serving” as Confederate guerrilla fighters. Rumors also abounded. Harper’s Magazine printed rumors that Southern men drank from goblets made from Yankee skulls, and women wore necklaces of Yankee teeth. It was no rumor, however, that a Southerner murdered Lincoln. The point of all this conjecture is that the North could have turned on the South for vengeance. The federal government of the United States could have hanged Jefferson Davis, Alexander Stephens, Robert E. Lee, and every man who had served as an officer in the Confederate Army above the rank of, say, Major. All other officers and politicians could have been exiled. The government could have erased all state boundaries and started again with states all the size of Texas, reducing the power of the South in the Senate. All plantation land could have been confiscated and redistributed to freedmen, an experiment that was even tried on a limited scale. None of these measures was done, however. The only Confederate officer executed for war crimes was Major Henry Wirtz, the commandant of Andersonville. Jefferson Davis, who had been caught in Irwinville, Georgia on May 10, 1865, was merely imprisoned for two years and had all charges of treason dropped against him in 1869. Robert E. Lee went on to be the President of what was renamed Washington and Lee University. Some Confederate officers fled the country, but they were not exiled. The South had been steeped in propaganda, too, however. They were told by their leaders that even Lincoln’s lenient plan for Reconstruction included, “emancipation, confiscation [of land], conflagration, and extermination.” The President was going to use, ironically, “the Assassin’s dagger, the midnight torch [arson], poison, famine, and pestilence.” It was no rumor, however, that the North had an embarrassing prisoner of war camp at Elmira, New York, where 775 of 8,347 prisoners died in three months, a 9% death rate. Sherman’s March to the Sea was a bitter memory well on into the Twentieth Century. The South knew the March had included “unauthorized” plunder when Yankees had stolen the silver out of plantation houses along with other valuables and either carried them off or threw them in wells or ponds to come back for them later. A vengeful plan was proposed to Robert E. Lee by some of his junior officers on the morning of the day of his surrender at Appomattox Courthouse. Foreshadowing halfa-dozen 20th-century insurgencies including Afghanistan (against the Russians), Cuba, Iraq (against the US), and the forty-year struggle in Columbia, these Confederates suggested that the Army disband to form bands of guerrilla fighters. They said determined troops could hold out in the Appalachian Mountains for years while they sabotaged, assassinated, and robbed. Some even cut through the first Union assault to top a rise only to observe a “sea of blue” surrounding them. Had they attempted to act on their idea earlier, historians guess that the Confederacy might have fought on for at least another decade. Some of these officers were the ones to exile themselves to Canada and Mexico. Lee was against the plan from the beginning. He urged all his men to surrender, to restore law and order, to re-establish agriculture and commerce, and to promote education and general rebuilding. This moment is when Lee saved the Union. Don’t rule out the blacks. Former slaves could have easily sought vengeance and gone renegade, unleashing violence across the South including murder and the rape of white women in payment for centuries of sexual exploitation of their women. Blacks could have demanded and carved out a nation within a nation similar to a huge Indian reservation where no whites would be allowed. Southerners, indeed, feared these things would happen. Blacks did expect to obtain the former masters’ lands, but they did not seize them. This scenario is a third disaster that did not occur. In fact, blacks said they would strive for “peace, friendship, and good will toward all men—especially toward our fellow white citizens among whom our lot is cast.” That line is among the most incredible ever uttered in US history! I am sure the South was grateful that they had permitted their slaves to become Christians. Blacks actually fought in political struggles to return former Confederates to full citizenship, including voting and holding public office (which the 14th Amendment forbade). After all the sacrifice of the Civil War, the Union was preserved; the slaves were freed. Radical changes took root in our society, but Reconstruction was by no means as revolutionary or as bloody as it could have been. In fact, the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments were stymied by the South and did not at all accomplish their purpose until approximately 100 years after the Civil War. We will need to take up the limitations on Reconstruction that made the Civil Rights Movement necessary in our next installment.