Chapter 2

... • The acceleration is constant for all objects in free fall. During each second of fall the object gains 9.8 m/s in velocity. • This gain is the acceleration of the falling object, 9.8 m/s2, or 32 ft/s2. The symbol g is used for this. Thus g= 9.8 m/s2, or 32 ft/s2 • The acceleration of free falling ...

... • The acceleration is constant for all objects in free fall. During each second of fall the object gains 9.8 m/s in velocity. • This gain is the acceleration of the falling object, 9.8 m/s2, or 32 ft/s2. The symbol g is used for this. Thus g= 9.8 m/s2, or 32 ft/s2 • The acceleration of free falling ...

Physics Final Study Guide: Practice Problems Compare the

... C rest. What is the car’s acceleration? 3) A skateboard rider starts from rest and maintains a constant acceleration of +0.50 m/s 2 for 8.4s. What is the rider’s displacement during this time? 4) A rolling ball has an initial velocity of -1.6 m/s. a. If the ball has a constant acceleration of -0.33m ...

... C rest. What is the car’s acceleration? 3) A skateboard rider starts from rest and maintains a constant acceleration of +0.50 m/s 2 for 8.4s. What is the rider’s displacement during this time? 4) A rolling ball has an initial velocity of -1.6 m/s. a. If the ball has a constant acceleration of -0.33m ...

hw4,5

... to equally accelerate a 10-kg brick, one would have to push with A) just as much force. B) 10 times as much force. C) 100 times as much force. D) one tenth the amount of force. E) none of these. ...

... to equally accelerate a 10-kg brick, one would have to push with A) just as much force. B) 10 times as much force. C) 100 times as much force. D) one tenth the amount of force. E) none of these. ...

Section 3: Circular Motion

... Notice how instead of drawing an x and y axis as we would have for previous problems instead we have drawn a system of coordinates that is more appropriate for a problem involving circular motion. The two axis are the centripetal (c) and tangential (t) axis here. The two forces that act on the ball ...

... Notice how instead of drawing an x and y axis as we would have for previous problems instead we have drawn a system of coordinates that is more appropriate for a problem involving circular motion. The two axis are the centripetal (c) and tangential (t) axis here. The two forces that act on the ball ...

document

... (A) a satellite orbiting Earth in a circular orbit (B) a ball falling freely toward the surface of Earth (C) a car moving with a constant speed along a straight, level road (D) a projectile at the highest point in its trajectory ...

... (A) a satellite orbiting Earth in a circular orbit (B) a ball falling freely toward the surface of Earth (C) a car moving with a constant speed along a straight, level road (D) a projectile at the highest point in its trajectory ...

Newton`s First Law

... is getting rid of the effects of friction. When we said no force earlier on it should really have been no unbalanced force. In the example of the stone the weight of the stone is just balanced by the upward force of the ice - the two forces on the stone are equal and so it continues moving at a cons ...

... is getting rid of the effects of friction. When we said no force earlier on it should really have been no unbalanced force. In the example of the stone the weight of the stone is just balanced by the upward force of the ice - the two forces on the stone are equal and so it continues moving at a cons ...

File

... (b) What does the scale read if the cab is stationary or moving upward at a constant 0.50 m/s? (c) What does the scale read if the cab accelerates upward at 3.20 m/s2 and downward at 3.20 m/s2 ? ...

... (b) What does the scale read if the cab is stationary or moving upward at a constant 0.50 m/s? (c) What does the scale read if the cab accelerates upward at 3.20 m/s2 and downward at 3.20 m/s2 ? ...

Physics 106a/196a – Problem Set 2 – Due Oct 13,...

... 2. (106a) A lunar landing craft approaches the moon’s surface. Assume that one-third of its weight is fuel, that the exhaust velocity from its rocket engine is 1500 m/s, and that the acceleration of gravity at the lunar surface is one-sixth of that at the earth’s surface. How long can the craft hove ...

... 2. (106a) A lunar landing craft approaches the moon’s surface. Assume that one-third of its weight is fuel, that the exhaust velocity from its rocket engine is 1500 m/s, and that the acceleration of gravity at the lunar surface is one-sixth of that at the earth’s surface. How long can the craft hove ...

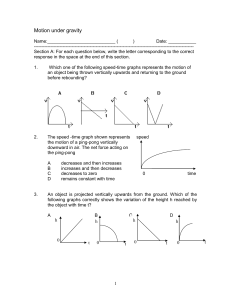

Quiz on Motion under gravity

... ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Section A: For each question below, write the letter corresponding to the correct response in the space at the end of this section. ...

... ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Section A: For each question below, write the letter corresponding to the correct response in the space at the end of this section. ...

Mass versus weight

In everyday usage, the mass of an object is often referred to as its weight though these are in fact different concepts and quantities. In scientific contexts, mass refers loosely to the amount of ""matter"" in an object (though ""matter"" may be difficult to define), whereas weight refers to the force experienced by an object due to gravity. In other words, an object with a mass of 1.0 kilogram will weigh approximately 9.81 newtons (newton is the unit of force, while kilogram is the unit of mass) on the surface of the Earth (its mass multiplied by the gravitational field strength). Its weight will be less on Mars (where gravity is weaker), more on Saturn, and negligible in space when far from any significant source of gravity, but it will always have the same mass.Objects on the surface of the Earth have weight, although sometimes this weight is difficult to measure. An example is a small object floating in a pool of water (or even on a dish of water), which does not appear to have weight since it is buoyed by the water; but it is found to have its usual weight when it is added to water in a container which is entirely supported by and weighed on a scale. Thus, the ""weightless object"" floating in water actually transfers its weight to the bottom of the container (where the pressure increases). Similarly, a balloon has mass but may appear to have no weight or even negative weight, due to buoyancy in air. However the weight of the balloon and the gas inside it has merely been transferred to a large area of the Earth's surface, making the weight difficult to measure. The weight of a flying airplane is similarly distributed to the ground, but does not disappear. If the airplane is in level flight, the same weight-force is distributed to the surface of the Earth as when the plane was on the runway, but spread over a larger area.A better scientific definition of mass is its description as being composed of inertia, which basically is the resistance of an object being accelerated when acted on by an external force. Gravitational ""weight"" is the force created when a mass is acted upon by a gravitational field and the object is not allowed to free-fall, but is supported or retarded by a mechanical force, such as the surface of a planet. Such a force constitutes weight. This force can be added to by any other kind of force.For example, in the photograph, the girl's weight, subtracted from the tension in the chain (respectively the support force of the seat), yields the necessary centripetal force to keep her swinging in an arc. If one stands behind her at the bottom of her arc and abruptly stops her, the impetus (""bump"" or stopping-force) one experiences is due to acting against her inertia, and would be the same even if gravity were suddenly switched off.While the weight of an object varies in proportion to the strength of the gravitational field, its mass is constant (ignoring relativistic effects) as long as no energy or matter is added to the object. Accordingly, for an astronaut on a spacewalk in orbit (a free-fall), no effort is required to hold a communications satellite in front of him; it is ""weightless"". However, since objects in orbit retain their mass and inertia, an astronaut must exert ten times as much force to accelerate a 10‑ton satellite at the same rate as one with a mass of only 1 ton.On Earth, a swing set can demonstrate this relationship between force, mass, and acceleration. If one were to stand behind a large adult sitting stationary on a swing and give him a strong push, the adult would temporarily accelerate to a quite low speed, and then swing only a short distance before beginning to swing in the opposite direction. Applying the same impetus to a small child would produce a much greater speed.