* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Implementation Strategies for EMAR

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

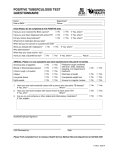

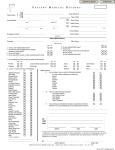

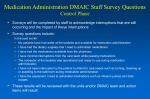

Section 4.13 Implement Implementation Strategies for E-MAR Distinguish among the different forms of electronic medical administration record (EMAR), and use a set of tools developed by the American Hospital Association, Health Research Trust and the Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Time needed: 20 hours Suggested prior tools: NA Introduction This tool uses the term EMAR to describe a general class of applications relating to electronic assistance with medication administration and its documentation. Use this tool to help you distinguish among the different forms of EMAR, and to direct you to a set of tools that have been developed by the American Hospital Association, Health Research Trust, and the Institute for Safe Medication Practices. How to Use 1. Determine the nature of EMAR you are implementing. The form of EMAR you are implementing has a big impact on its capabilities and drives the policy and procedure changes you may need to make. 2. If you have not done so already, engage all stakeholders in the process of implementation. While the predominant user of EMAR is nursing, individuals who provide pharmacy, quality improvement, and procurement services are very important to have on board. Even if it is necessary to obtain the services of a pharmacy consultant, this can be a valuable investment. A physician champion also can help ensure that the physician community understands the new processes and how nurses will utilize the system in administering medications, monitoring residents’ reactions, and documenting their activities. Ensuring that key stakeholders are on board and involved can reduce confusion and increase trust in the new system. 3. Conduct workflow and process improvement mapping to determine how the application being implemented may change current workflows and processes. Ideally during your planning for HIT acquisition you have mapped current workflows and processes and can now identify processes you want to be sure are included in the new application and how improvements can be made. Standardization will be needed, and there will be some processes that may support resident safety but which are a bit foreign to staff. 4. Afford the opportunity for all nursing staff and others, as applicable, to be fully trained. Stress the importance of following policies and procedures and reporting any issues or concerns regarding use. Because these processes are often quite different from manual processes, staff members who may be uncertain about how to handle exceptions often revert back to manual processes. As a result, workarounds are created, continue, and can produce misleading or erroneous outcomes that are potentially detrimental to residents and/or the organization. Section 4 Implement—Implementation Strategies for E-MAR - 1 5. Determine whether your organization has the applications, technology, and operational elements in place to move forward to the bar-code medication administration record (BCMAR) form of EMAR when that may be desired. Forms of EMAR Following are several possible forms of EMAR applications: 1. Electronic MAR forms. These paper forms provide the medication and its administration information printed in the typical MAR flow sheet structure. The forms are derived as a result of entering medication orders into the system. The primary benefits of these forms are reducing nursing transcription errors and saving nursing time. 2. Bedside medication verification (BMV) systems. These systems provide MAR formats online to enable nursing staff to see what medications must be administered to whom, when, and how. They also provide for documenting medication administration . In addition to reducing transcription errors, timing reminders should aid in timely administration of medications. Other patient safety features in these products may include the ability to: visually compare the medication being given against a picture on the computer; provide nursing staff with alerts to potential contraindications as another check between the provider, pharmacist, and nurse; and enable drug knowledge base (DKB) reference. 3. Bar code MAR (BC-MAR) systems. These systems add the dimension of positive patient identification, and thus afford the medication five rights: right patient, right drug, right time, right dose, and right route. This is accomplished through an application that is similar to the BMV in that it alerts the nursing staff when medications should be given, provides clinical decision support on potential medication contraindications and reference to a DKB, and verifies through the bar code reading system that the five rights have been assured. Nurses administering medications wand the bar code reader over the resident’s bar-coded wrist band, the bar-coded unit dose of the medication, and the nurse’s bar- coded identification badge. The system checks for right patient, right drug (including dose and route), and right time (because the bar coding actions both time stamp and document the administration). Some BC-MAR systems also may be designed to provide a unit dose dispensing drawer that opens to the specific unit dose for the resident identified. Challenges to Capabilities Of course, all of these systems depend on the right medication being ordered and the order correctly populating the EMAR system. Following are some key challenges: If the nursing home does not yet have a computerized provider order entry (CPOE) system, transcription of the medications ordered still must be done manually. The BC-MAR system also depends on having bar-coded unit doses available. For some nursing homes, this can be a significant challenge. Drugs may not be packaged in unit dose form, which may be more expensive. It is possible to purchase a unit dose drug packaging system, but this is another application that adds cost and time to the process. Finally, not all drugs are easily bar coded. Drugs administered through IV bags can be challenging, though not impossible. Another challenge is that the naming conventions of the drugs used in the E-MAR/BC-MAR may not be the same as the drug names in the ordering system. Pharmacy systems generally record drug names using the National Drug Code (NDC), which is a naming convention used in naming packages of drugs. The name of the manufacturer, brand name, serial number, and other such information are all embedded in this code. However, when physicians enter medications into CPOE systems and when nurses record these medications on a MAR, they Section 4 Implement—Implementation Strategies for E-MAR - 2 may use terminology that is more clinically relevant. In addition, physicians may leave it up to the pharmacy to supply the specific brand stocked, or to substitute a generic equivalent. A closed-loop medication management system with CPOE, pharmacy interface, and EMAR/BC-MAR would enable mapping to occur automatically so that there is equivalency between the two naming conventions. If the systems are standalone or not well-integrated without the mapping on the naming conventions, the result can be confusing. Workarounds are a very common challenge in using EMAR systems. One of the most frequent is to print extra copies of the barcoded wrist bands worn by residents and barcode them at the nursing station before actually administering the medication, instead of at the time of administration. A classic article, entitled Technology Implementation and Workarounds in the Nursing Home, available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2274876/, describes many such workarounds. Workaround are so common, in fact, that a typology of EHR workarounds in small- to medium-size primary care practices has been created with the hopes that it will be used to identify and resolve workarounds in these settings. The typology can be adapted for other settings. This article, which requires membership in the American Medical Informatics Association or a subscription to the Journal of AMIA is available at: http://jamia.bmj.com/content/early/2013/07/31/amiajnl-2013-001686.abstract. Policy and Procedure Changes When any form of EMAR is adopted, the nursing home may see more reports of medication errors. The following are common types of medication errors: incomplete patient information (e.g., not knowing about patients' allergies, other medicines they are taking, previous diagnoses, and current lab results) unavailable drug information (e.g., lack of up-to-date warnings) miscommunication of drug orders, caused by poor handwriting, confusion between drugs with similar names, misuse of zeroes and decimal points, confusion of metric and other dosing units, and inappropriate abbreviations inappropriate labeling as a drug; prepared and repackaged into smaller units environmental factors (e.g., lighting, heat, noise, interruptions) that can distract health professionals from their medical tasks It is important to review policies before you implement EMAR (and other components of medication management), define terms very carefully, and recognize that there are likely not more actual errors, but better reporting. Errors also should be classified by their type, including those that are adverse reactions that may have been anticipated, and near misses. Different organizations use different definitions for these concepts, often driven by required reporting systems. The following definitions are supplied by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/cliniciansproviders/resources/nursing/resources/nurseshdbk/HughesR_MAS.pdf. Adverse drug event. In some reporting systems, this is a widely encompassing term referring to actual errors, near misses, and adverse drug reactions. In other reporting systems, adverse drug event refers solely to harm caused by an actual error in medication management. The source of the error may be one or more sources, as described above. In implementing an EMAR system, one of the most frequent increases in reported errors is timing errors. Many EMAR systems identify timing errors using a very narrow time window. It is important to reach agreement on an acceptable window of time, and whether the window Section 4 Implement—Implementation Strategies for E-MAR - 3 is smaller than before due to other reporting requirements. Workflows and processes should be studied to determine the impact of this change in definition. Near miss. An event or situation that did not produce injury, but only because of chance. This good fortune might reflect robustness of the individual (e.g., a person with a specific medication allergy receives a very similarly compounded medication, but has no reaction) or a fortuitous, timely intervention (e.g., a nurse happens to realize that a physician wrote an order in the wrong chart). EMAR systems often are able to identify these near misses when an alert or reminder is invoked in the clinical decision support component of the application. Adverse drug reaction. This reaction is an adverse effect produced by the use of a medication in the recommended manner. These effects range from nuisance effects (e.g., dry mouth with anticholinergic medications) to severe reactions (e.g., anaphylaxis due to severe allergy). In addition to policies that define errors, another area of policy that should be considered relates to adherence to procedures. As the EMAR systems significantly change workflows, it is very important to (1) engage nursing staff in all aspects of workflow and process changes during implementation, and (2) ensure that these changes are monitored for adherence and potential need to make adjustments. Unfortunately, many systems are installed with a specific workflow change that staff members have not been engaged in understanding or discussing. As a result, staff members may find workarounds, resulting in significantly less safety improvement than anticipated, and productivity issues. You should be flexible in studying these issues and working through necessary changes, while freezing critical changes into place. Assessing Readiness Although old, the following Web site has an excellent tool, entitled Assessing Bedside Bar-coding Readiness, as well as other useful tools for managing the MAR implementation. This document is used with permission, copyright 2002, by the American Hospital Association, Health Research & Educational Trust, and the Institute for Safe Medication Practices: www.medpathways.info/medpathways/tools/content/3_2.pdf Copyright © 2014 Section 4 Implement—Implementation Strategies for E-MAR - 4 Updated 03-19-2014