* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Fentanyl citrate - Therapeutic Goods Administration

Survey

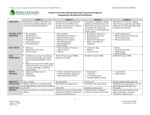

Document related concepts

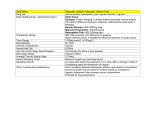

Transcript