* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Print | Close Window

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

Print | Close Window

Note: Large images and tables on this page may necessitate printing in landscape mode.

|

Tintinalli's Emergency Medicine > Section 7: Cardiovascular Disease > Chapter 49.

Approach to Chest Pain >

Overview

Approximately 5 percent of all U.S. ED visits, or about 5 million visits a year, are for

chest pain, but accurate diagnosis remains a challenge.1,2 This chapter covers the

approach to acute chest pain, with attention to identifying patients with potentially

serious disorders.

Pathophysiology of Chest Pain

Stimulation of visceral or somatic afferent pain fibers results in two distinct pain

syndromes. The dermis and parietal pleura are innervated by somatic pain fibers, which

enter the spinal cord at specific levels and are arranged in dermatomal patterns. Visceral

pain fibers are found in internal organs, such as the heart and blood vessels, the

esophagus, and the visceral pleura. These visceral pain fibers enter the spinal cord at

multiple levels and map to areas on the parietal cortex corresponding to the cord levels

shared with the somatic fibers. Pain from somatic fibers is usually easily described,

precisely located, and experienced as a sharp sensation, whereas pain from visceral fibers

is more difficult to describe and is imprecisely localized. Accordingly, those experiencing

visceral pain are more likely to use terms such as discomfort, heaviness, or aching.

Patients frequently misinterpret the origin of visceral pain, because it is often referred to a

different area of the body corresponding to an adjacent somatic nerve. For example,

diaphragmatic irritation can present as shoulder pain, and arm pain may actually

represent myocardial ischemia.

Gender, age, comorbidities, medications, drugs, and alcohol may interact with

psychological and cultural influences to affect the patient's perception and

communication of pain.

Definitions

The phrase acute chest pain, commonly used in emergency medicine, deserves definition.

The term acute means of sudden or recent onset. While there is no precise time period

defined, in common practice acute means that the patient stops his or her usual activity to

seek medical attention, typically within minutes to hours. Some studies of acute chest

pain patients in the ED limit entry to those with chest pain of less than 24-h duration. The

term chest in this context means a location described by the patient on the anterior thorax,

from xiphoid to suprasternal notch and between the right and left midaxillary lines. This

is because the major serious thoracic disorders typically manifest symptoms localized to

the anterior thorax. While it is true that pain localized to the back, between the base of the

neck and the lumbar region, is on the thorax cage, in isolation, pain localized to this

region is approached differently (see Chap. 282). That said, there are occasional patients

with serious and life-threatening intrathoracic disorders who will manifest a location of

their most intense pain outside the boundaries noted above. In addition, some patients

may have migratory pain that has moved out of the anterior chest by the time the patient

reaches medical attention. Therefore, clinicians are encouraged to include within their

differential diagnosis important and significant intrathoracic disorders when patients

describe pain in adjacent regions; e.g., epigastric, neck and jaw, and arm. The term pain

describes a noxious uncomfortable sensation. However, pain perception and description

vary widely, and patients may use terms such as ache or discomfort. Alternative

descriptions are common in the elderly. Similar to alternative locations, clinicians should

be attuned to variation in the patient's description of the noxious sensation. In summary,

acute chest pain refers to (1) recent onset, typically less than 24 h, that causes the patient

to seek prompt medical attention, (2) location described on the anterior thorax, and (3) a

noxious uncomfortable sensation distressing to the patient.

Initial Approach

The initial approach to acute chest pain recognizes that some causes are serious and lifethreatening, and prompt medical attention may prevent death and limit morbidity.

Therefore, patients should be triaged promptly. Patients with visceral-type chest pain

(defined below), significantly abnormal pulse or blood pressure measurements, or with

dyspnea should be placed directly into a treatment bed, a cardiac monitor initiated, an

intravenous line established, oxygen administered, and an ECG ordered. Other less welldefined patients also deserve expeditious evaluation, and experienced triage officers and

nurses often have a "gut" feeling about certain patients; that insight should be respected.

The initial evaluation should focus on immediate life threats: ensuring adequate airway,

breathing, and circulation. The vital signs should be assessed and repeated at regular

intervals as determined by the patient's condition. The initial history should focus on

specific questions concerning the character of the chest pain, the presence of associated

symptoms, and a history of cardiopulmonary conditions. The patient is asked to grade

pain intensity in order to follow response to therapy. A 0 to 10 scale is commonly used,

with 10 being the worst pain the patient can imagine and 0 being no pain at all. Focused

cardiac, pulmonary, and vascular examinations should follow.

If immediate life threats are not detected or have already been addressed, a more

extensive evaluation can be preformed. This "secondary survey" consists of a history that

defines symptoms more precisely. Chest pain should be assessed like other pain

syndromes, with specific questions concerning quality, location, radiation or migration,

severity, time and character of onset, progression, provoking factors, relieving factors,

and associated symptoms. If the pain has been episodic, the frequency of pain episodes

should be assessed over the past weeks to better determine progression. Risk factors for

cardiopulmonary disease should be assessed. The physical examination during this phase

should complete those body systems not evaluated initially as well as rechecking

abnormalities noted before. Many organizations have developed structured history and

physician examination forms for acute chest pain to direct the information-gathering

process and organize the diagnostic approach. Such structured records are particularly

helpful to less experienced physicians. Further diagnostic testing is directed by the

history and physical examination.

Categorization

A useful initial approach is to classify patients into three categories: (1) chest wall pain,

(2) pleuritic or respiratory chest pain, and (3) visceral chest pain. Chest wall pain is a

somatic pain, usually described as sharp in quality, that can be precisely localized (often

with one fingertip) and is reproducible by direct palpation and/or chest wall movement

during stretching or twisting. Pleuritic chest pain is also a somatic pain, usually described

as sharp in quality that is distinctly worsened by breathing or coughing. The term

pleuritic is potentially confusing; more than the pleura moves during respiration, and

disorders other than "pleurisy" may be worse with respiration. Visceral chest pain is

poorly localized and usually described as aching or heaviness. Important causes of chest

pain within each category are noted in Table 49-1.

Table 49-1 Important Causes of Acute Chest Pain

Chest Wall Pain Pleuritic Pain Visceral Pain

Costosternal syndrome Pulmonary embolism Typical exertional angina

Costochrondritis (Tietze syndrome) Pneumonia Atypical (nonexertional) angina

Precordial catch syndrome Spontaneous pneumothorax Unstable angina

Slipping rib syndrome Pericarditis Acute myocardial infarction

Xiphodynia Pleurisy Aortic dissection

Radicular syndromes Pericarditis

Intercostal nerve syndromes Esophageal reflux or spasm

Fibromyalgia Esophageal rupture

Mitral valve prolapse

A very useful principle in the clinical assessment of acute chest pain is that, with rare

exception, chest pain diagnosis is a composite picture, no one fact or observation make

the diagnosis. The challenge to the clinician is to take the often-confusing history and

nondiagnostic physician examination and select the useful features that guide further

assessment, management, and disposition.

Assessment of risk factors for cardiovascular disease can play a role in patient

assessment. Specifically, the presence of risk factors for coronary artery disease (cigarette

smoking, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, family history), aortic dissection

(middle aged, male gender, hypertension, Marfan syndrome), and pulmonary embolism

(hypercoagulable diathesis, malignancy, recent immobilization or surgery) are useful in

judging the probability of these diagnoses. Likewise, age can be used to assess the

probability of atherosclerotic disease; clinically significant coronary artery disease is rare

in patients under the age of 30. Acute cocaine use has been associated with acute

myocardial infarction, and chronic cocaine use is associated with accelerated

atherosclerosis and severe coronary artery disease (see Chap. 168). However, youth or

absence of risk factors does not completely eliminate any potentially serious cause of

acute chest pain.

The patient's medical record should be reviewed. The current ECG should be compared

with previous tracings. Results of prior cardiac studies (echocardiograms, stress testing,

or catheterizations), esophageal studies (endoscopy, oral contrast swallowing studies),

gastrointestinal studies (ultrasound, computed tomography), or pulmonary studies

(spirometry) should be reviewed and present symptoms interpreted in comparison with

these results. In general, cardiac stress studies within the previous 6 months and coronary

angiography within the prior 2 years are considered to likely reflect the current state of

the coronary circulation.

A practice to be decried is the use of therapeutic trials in acute chest pain; usually in the

form of (1) a "gastrointestinal (GI) cocktail" containing an antacid, antispasmodic, and

local anesthetic for gastroesophageal reflux, (2) nitroglycerin for myocardial ischemia,

and (3) nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories for chest wall pain. The placebo effect makes it

difficult to interpret a positive response; patients with definite myocardial ischemia have

been reported as experiencing complete pain relief with a GI cocktail. In addition,

nitroglycerin is a smooth muscle dilator and may produce relief in esophageal spasm and

biliary colic as well as myocardial ischemia. The analgesic properties of nonsteroidal

anti-inflammatories are not specific for any location.

Ischemic Equivalents

A confounding observation is that many patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS,

defined below), perhaps as high as 40 percent, do not describe chest pain as their

predominant symptom.3 The absence of chest pain leads to delayed or inadequate antiischemic therapy and increased inhospital mortality.4

Truly silent myocardial ischemia does occur, but these patients are not likely to come to

the ED. For those that do, ischemic equivalents or atypical presentations are important to

note: dyspnea at rest or with less exertion compared to the patient's previous baseline;

shoulder, arm, or jaw discomfort; nausea; lightheadedness; generalized weakness; acute

change in mental status; or diaphoresis. Epigastric or upper abdominal discomfort can be

the presenting symptom of myocardial ischemia. Patients with sensory impairment due to

diabetes, advanced age, psychiatric disease, or altered mental status are more likely to

present with atypical symptoms with ACS. Atypical presentations of ACS also occur

more frequently in women and non-white populations compared to white males.5

Differential Diagnosis

When patients present with acute chest pain due to myocardial ischemia, the term acute

coronary syndrome, or ACS, is used because, on initial assessment, it is not possible to

determine if the patient has an acute myocardial infarction (AMI) or unstable angina

(UA). ACS is a common cause of acute chest pain; in a typical ED population of adults

over the age of 30 presenting with visceral-type chest pain, about 15 percent will have

AMI and 25 to 30 percent will have UA.1

The pain of myocardial ischemia is almost always retrosternal and diffuse, usually

described as a heaviness or pressure, and commonly radiates, usually to the neck or left

arm (see Chap. 50). In exertional angina, the pain is episodic, lasting minutes (usually

<10 min and not seconds or hours), provoked by exertion, and relieved by rest or

sublingual nitroglycerin. Exertional angina is most often due to atherosclerotic disease of

the epicardial coronary arteries that restricts blood flow. In atypical angina, the pain is the

same as that with exertional angina, but pain occurs at rest. Atypical angina appears to be

caused by coronary artery spasm. In about two-thirds of patients with atypical angina,

coronary artery lesions are seen, and patients may have exertional as well as rest pain. In

both exertional angina and atypical angina, the pattern is stable in terms of frequency of

episodes, severity, ease of provocation, and response to rest or nitroglycerin. In UA, the

episodic anginal pain has changed its pattern; it is either (1) of new onset (less than 1 to 2

months), (2) more frequent, easily provoked, more severe, or difficult to relieve, or (3)

occurring at rest for prolonged spells (>20 min). UA is a potentially serious condition and

patients are at high risk for early AMI or death. In AMI, the pain is usually persistent

(>20 min), severe, and associated with symptoms of dyspnea, diaphoresis, or nausea.

In ACS, the most useful test is an ECG for both detecting myocardial ischemia and risk

stratification. Using the initial ECG, the incidence of AMI is approximately 80 percent

for patients with new ST-segment elevation greater than 1 mm in two contiguous leads,

about 20 percent in patients with new ST-segment depression or T-wave inversion, but

less than 4 percent in patients without either of these two patterns.

Pulmonary embolism is common and life-threatening and is a diagnosis that can be

missed in the ED due to the frequently atypical nature of its presentation. Pulmonary

embolism can manifest with any combination of chest pain, dyspnea, syncope, shock,

and/or hypoxia (see Chap. 56). The pain associated with a PE occurs when inflammation

of the parietal pleura overlying the infarction causes chest pain that is generally sharp and

related to respiration. Dyspnea, fever, cough, and/or hemoptysis also may be present, and

the chest wall may be tender to palpation. Patients with massive PEs often present with

unstable vital signs and the classic presentation of sharp, pleuritic chest pain and dyspnea

associated with tachypnea, tachycardia, and hypoxemia. A clinical scoring system may be

useful in categorizing patients into low (about 10 percent), intermediate (about 40

percent), and high (about 80 percent) prevalence for PE.6

Risk factors for aortic dissection include atherosclerosis, uncontrolled hypertension,

coarctation of the aorta, bicuspid aortic valves, aortic stenosis, Marfan syndrome, EhlersDanlos syndrome, and pregnancy (see Chap. 58). The pain of aortic dissection, i.e.,

midline substernal chest pain, is classically described as tearing, ripping, or searing and

radiating to the interscapular area of the back. Typically, the pain is at its worst at

symptom onset and is often felt above and below the diaphragm. Symptoms of

"secondary" pathologies resulting from arterial branch occlusions, such as stroke, AMI,

or limb ischemia, may overshadow the clinical presentation of the dissection and make an

accurate diagnosis difficult. No combination of clinical factors or chest radiography

findings are adequate to exclude the diagnosis of aortic dissection, and specific imaging

studies are usually required.7

Spontaneous pneumothorax may occur due to sudden changes in barometric pressure, in

smokers or patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or idiopathic pleural bleb

disease, or in those with another pulmonary pathology (see Chap. 66). Patients usually

complain of a sudden, sharp, lancinating, pleuritic chest pain and dyspnea. Auscultation

of the lungs may reveal absence of breath sounds on the ipsilateral side and

hyperresonance to percussion, but clinical impression alone is unreliable. Diagnosis of a

simple pneumothorax is made by chest radiography.

Esophageal rupture (Boerhaave syndrome) is a rare but potentially life-threatening cause

of chest pain. Patients classically present with a history of substernal, sharp chest pain of

sudden onset that occurs immediately after an episode of forceful vomiting (see Chap.

75). The patient is usually ill-appearing, dyspneic, and diaphoretic. The physical

examination is often normal but may reveal evidence of pneumothorax or subcutaneous

air. Chest radiography may be normal or may demonstrate pleural effusion (left more

common than right), pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, pneumoperitoneum, and/or

subcutaneous air. The diagnosis can be confirmed by a study with water-soluble contrast.

The pain of acute pericarditis is typically acute, sharp, severe, and constant (see Chap.

55). It is usually described as substernal, with radiation to the back, neck, or shoulders,

and is exacerbated by lying down and by inspiration. It is classically described as being

relieved by leaning forward. A pericardial friction rub is the most important diagnostic

finding. The ECG may show diffuse ST-segment elevation and T-wave inversion. In

addition, depression of the PR segment is a highly specific ECG finding for pericarditis.

Pneumonia can produce chest pain or discomfort that is usually sharp and pleuritic (see

Chap. 63). It is usually associated with fever, cough, and possibly hypoxia. Physical

examination may reveal rales over the affected lobes, decreased breath sounds, and signs

of consolidation (i.e., bronchial breath sounds). A chest radiograph confirms the

diagnosis.

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) is the most frequently diagnosed cardiac valvular

abnormality and is more commonly diagnosed in women than in men. The discomfort of

MVP often occurs at rest, is atypical for myocardial ischemia, and can be associated with

dizziness, hyperventilation, anxiety, depression, palpitations, and fatigue (see Chap. 54).

The discomfort may be related to papillary muscle tension, and many patients benefit

from the administration of -adrenergic blocking agents. Two-dimensional

echocardiography is the diagnostic tool of choice and, with physical examination

findings, helps to stratify patients into high- and low-risk categories for developing

serious complications. Palpitations and every type of supraventricular or ventricular

dysrhythmia have been associated with MVP.

Musculoskeletal or chest wall pain syndromes are characterized by highly localized,

sharp, positional chest pain. Pain that is completely reproducible by light to moderate

palpation of a discrete area of the chest wall often represents pain of musculoskeletal

origin, although chest wall tenderness occurs in some patients with PE and myocardial

ischemia. Costochondritis is an inflammation of the costal cartilages and/or their sternal

articulations and causes chest pain that is variably sharp, dull, and/or increased with

respirations. Tietze syndrome is a particular cause of costochondral pain related to

fusiform swelling in one or more upper costal cartilages and has a pain pattern similar to

that of other costochondral syndromes. Xiphodynia is another inflammatory process that

causes sharp, pleuritic chest pain reproduced by light palpation over the xiphoid process.

Texidor twinge or precordial catch syndrome is described as a short, lancinating chest

discomfort that occurs in episodic bunches lasting 1 to 2 min near the cardiac apex

associated with inspiration and poor posture and inactivity.

Gastrointestinal disorders cannot be reliably discriminated from myocardial ischemia by

history and examination alone. Dyspepsia syndromes, including gastroesophageal reflux,

often produce pain described as burning or gnawing, usually in the lower half of the

chest, and often accompanied by a brackish or acidic taste in the back of the mouth (see

Chap. 75). The recumbent position usually exacerbates the symptoms, and although the

pain is typically relieved with antacids, this therapeutic response also can be observed in

myocardial ischemia. Esophageal spasm is often associated with reflux disease and is

characterized by a sudden onset of dull, tight, or gripping substernal chest pain,

frequently precipitated by the consumption of hot or cold liquids or a large food bolus

and often lasting for hours (see Chap. 75). The pain also responds to sublingual

nitroglycerin (although supposedly with a slight delay).

Peptic ulcer disease is classically characterized as a postprandial, dull, boring pain in the

midepigastric region (see Chap. 77). Patients often describe being awakened from sleep

by discomfort. Duodenal ulcer pain is usually relieved after eating food, in contrast to

gastric ulcer symptoms, which are often exacerbated by eating. Symptomatic relief is

usually achieved by antacid medications. Acute pancreatitis and biliary tract disease

present with right upper quadrant or epigastric pain and tenderness but also can present

with chest pain.

Panic disorder (PD) is defined as a syndrome characterized by recurrent unexpected panic

attacks (discrete periods of intense fear or discomfort) with at least four of the following

symptoms: palpitations, diaphoresis, tremor, dyspnea, choking, chest pain or discomfort,

nausea, dizziness, derealization or depersonalization, fear of losing control or dying,

paresthesias, chills or hot flushes (see Chap. 292). The diagnosis can be made only in the

absence of direct physiologic effects of a substance disorder, a general medical condition,

or symptoms better accounted for by another mental disorder. Several studies have used

standardized screening tools to evaluate ED chest pain patients for PD and have reported

an incidence of 17 to 32 percent. In a small trial, investigators found that ED physicians

can successfully diagnose PD by using a brief screening procedure, and they suggested

that PD patients could benefit from the initiation of specific pharmacologic therapy

(serotonin reuptake inhibitors) in the ED.8 Many patients with PD and other anxiety

disorders have elevated baseline sympathetic tone, that may be an independent risk factor

for coronary artery disease (CAD). In fact, when all ED chest pain patients were screened

for PD, 25 percent of those screening positive had a discharge diagnosis of ACS (9.3

percent) or stable angina pectoris (15.7 percent).9 Thus, PD always must be considered a

diagnosis of exclusion.

Ancillary Testing

Ancillary testing in acute chest pain generally utilizes electrocardiography, measurement

of serum markers of myocardial injury, and/or imaging studies to detect intrathoracic

pathology. The specific studies are chosen according to the clinical circumstances. That

said, because ACS is the most common potentially serious cause of acute chest pain,

clinical studies and common practice focus on the use of the ECG and serum marker

measurement to detect or exclude acute myocardial injury. The remainder of this chapter

will focus on this topic. The use of ancillary tests in other conditions are discussed in

their respective chapters.

Electrocardiography

Due to the importance of early diagnosis of AMI (and, hence, reduced delay of

thrombolytic treatment), the American College of Cardiology/American Heart

Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines for management of patients with AMI recommend

standing orders that all patients with "ischemic-type pain" have a 12-lead ECG performed

within 10 min of arrival and that the ECG be handed directly to the treating physician for

immediate interpretation.10 Considering the difficulty of defining "ischemic-type" pain

and the frequency of atypical presentations, it may be prudent to extend this protocol to

all adult patients with chest pain or other symptoms of possible ischemia.

The normal myocardium depolarizes from endocardium to epicardium and repolarizes in

the opposite direction. Ischemic myocardium remains electrically less positive than

nonischemic myocardium at the end of depolarization. This creates an electrical potential

between normal and ischemic myocardium during depolarization and results in STsegment elevation in an overlying electrode. Conversely, if the electrode is located over

normal myocardium opposite an ischemic region, ST-segment depression will be seen. If

ischemia is limited to the subendocardial area, an overlying electrode will be separated

from the ischemic tissue by a layer of normal myocardium, resulting in an electrical

potential pointed inward from the normal to ischemic tissue, resulting in ST-segment

depression.

Myocardial ischemia can also delay the repolarization process. In extensive or transmural

ischemia, the direction of repolarization is reversed so that recovery occurs from

endocardium to epicardium, resulting in T-wave inversions in an overlying electrode. In

subendocardial ischemia, the delay does not alter the normal recovery process

(epicardium to endocardium), so T waves are not inverted. However, because normal

epicardium repolarization is unopposed due to delayed subendocardial repolarization, the

T wave in an overlying electrode may be larger than normal (called hyperacute T waves)

After infarction, the area of necrosis is electrically silent, not able to depolarize. During

ventricular depolarization, initial electrical activity will be generated in normal

myocardium, away from the infarcted area. This results in an electrical potential directed

from the infarcted area toward normal myocardium, causing an abnormal initial negative

deflection (pathologic Q waves) in the QRS complex of overlying electrodes.

Occasionally, small Q waves (called septal Q waves) are seen in the limb or lateral

precordial ECG leads. Pathologic Q-waves are distinguished by their duration (greater

than 40 ms) and depth (greater than 25 percent of the corresponding R wave).

The ECG is an important tool in the detection of acute infarction and conduction

blocks.11 Also, the ECG can help identify the infarct-related artery and help predict

reperfusion. The sensitivity of the initial ECG for the diagnosis of AMI has been

extensively studied. Approximately half of patients with AMI have diagnostic changes on

their initial ECG with new ST-segment elevation greater than 1 mm in two contiguous

leads. Another 20 to 30 percent will have new ST-segment or T-wave inversion

suggestive of myocardial ischemia. About 10 to 20 percent will have ST-segment

depressions and T-wave inversions similar to that seen on previous tracings. About 10

percent have nonspecific ST-segment and T-wave abnormalities. Only about 1 to 5

percent of AMI patients will have a truly normal initial ECG.

The sensitivity of the initial ECG in unstable angina is less well defined, probably

because the diagnosis is clinical as there is no "gold standard" against which to evaluate a

diagnostic test. In addition, the initial ECG would not be expected to be abnormal if a

patient with UA presents during a pain-free period.

The positive predictive value of the different ECG patterns has also been studied. For

new ST-segment elevation, the positive predictive value for AMI is about 80 percent. For

new ST-segment depression and T-wave inversions, the positive predictive value is about

20 percent for AMI and between 14 and 43 percent for UA. With acute chest pain and an

initial ECG showing preexisting ST-segment depressions and T-wave inversions, the

positive predictive value is about 4 percent for AMI and 21 to 48 percent for UA. Thus,

the standard 12-lead ECG is useful in conjunction with the clinical history for detection

of ACS.

Variations on the standard 12-lead ECG have been proposed. One approach uses a

continuous 12-lead ECG monitor that records (but does not print) a new 12-lead ECG

every 20 s. When the ST-segment baseline is altered from the previous tracing, an alarm

is raised and a copy of the new ECG is shared or printed. This technology is potentially

useful for monitoring patients with ongoing pain and a nondiagnostic initial ECG.12

Because of the costs, concerns regarding labile ST-segment and T-wave changes from

patient movement and respiration, and a lack of ED-based prospective studies,

continuous 12-lead ECG monitoring cannot be recommended for routine use.

Electrocardiograms with added leads—for a total of 15, 18, and 22 leads—have been

studied. In general, adding more leads increases the sensitivity for AMI detection, but

reduces specificity. The only generally agreed upon extension to the standard 12-lead

ECG is the use of right-sided precordial leads in the setting of acute inferior myocardial

infarction in order to detect right ventricular involvement.13

Risk stratification based on the initial ED ECG also has been suggested as a way of

improving ED decision making. Although the initial ECG cannot exclude AMI, stable

ED patients whose initial ECG is without ischemic changes are at low risk of subsequent

life-threatening complications and usually can be managed in a non-intensive-care

setting. Conversely, patients whose initial ECG demonstrates ischemic changes (STsegment depression or T-wave inversion), even in the absence of confirmed AMI, are at

significantly greater risk of short- and long-term morbidity and mortality and should be

managed accordingly.

Serum Markers of Myocardial Injury

Creatine Kinase, Creatine Kinase Isoenzymes, and Isoforms

Creatine kinase (CK; adenosine triphosphate creatine N-phosphotransferase) is an

intracellular enzyme involved in the transfer of high-energy phosphate groups from ATP

to creatine. Although found in small quantities in many tissues, CK is present in large

concentrations in cardiac and skeletal muscle and the brain. The enzyme is a dimer

composed of two subunits, each of which may be the M (muscle) type or the B (brain)

type, thus creating three distinct dimers, or isoenzymes: CK-BB, CK-MM, and CK-MB.

Type CK-BB predominates in brain tissue, whereas skeletal muscle consists mostly of

CK-MM, in addition to CK-MB in small amounts. The "cardiac isoenzyme," CK-MB,

accounts for 14 to 42 percent of total cardiac muscle enzyme activity, thus the

predominant enzyme in the heart is actually CK-MM.

The quantitative and temporal patterns of appearance and disappearance of CK and its

isoenzymes in the blood occur in a reproducible manner but can vary considerably

depending on the amount of CK released from cells, the amount of perfusion of damaged

tissues, and the rate of clearance by the reticuloendothelial system. The CK levels usually

become abnormally high within 4 to 8 h after coronary artery occlusion (onset of

symptoms), peak between 12 and 24 h, and return to normal between 3 and 4 days

(Figure 49-1). Reports of the sensitivity of total CK vary from 93 to 100 percent, whereas

the specificity is lower (57 to 86 percent), owing to the presence of CK in other tissues.

Thus, this marker's usefulness is limited. The CK-MB isoenzyme curve parallels the total

CK curve, with levels detectable 4 to 8 h after onset of symptoms (see Figure 49-1). Type

CK-MB may peak slightly earlier than total CK, and it is cleared more rapidly, usually

within 48 h (vs. 72 to 96 h). Using CK-MB and the ratio of CK-MB to total CK, most

studies have reported sensitivity and specificity to be greater than 95 percent. Cutoff

values vary between techniques, laboratories, and populations, but CK-MB values in

healthy controls may be up to 5 g/L and up to 5 percent of total CK. Historically, CK-MB

had been universally adopted as the gold standard for diagnosis of AMI. Although

specificity is generally improved over total CK, 37 conditions other than AMI have been

associated with elevated CK-MB levels (Table 49-2). Fortunately, most of these

conditions can be easily differentiated from AMI on clinical grounds. The relatively rapid

return of elevated CK-MB levels to normal is another potential disadvantage, because of

the possibility of missing the diagnosis in patients presenting later in the course of AMI.

However, this rapid clearance may be used to a different advantage, because it enables

the identification of infarct extension and reinfarction.

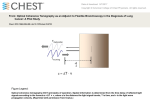

Fig. 49-1.

Typical pattern of serum marker elevation after AMI. Abbreviations: CK-MB =creatine

kinase-MB isoenzyme; cTnI = cardiac troponin I; cTnT = cardiac troponin T; LD1 =

lactate dehydrogenase isoenzyme 1; MLC = myosin light chain.

Table 49-2 Conditions Associated with Elevated CK-MB Levels

Common Uncommon Rare Unclear

Unstable angina, acute coronary ischemia Congestive heart failure Isolated case in

normal person Acromegaly

Inflammatory heart diseases Coronary artery disease after stress test Hypothermia

Cardiomyopathies Angina pectoris Rocky Mountain spotted fever

Circulatory failure and shock Valvular defects Typhoid fever

Cardiac surgery Tachycardia Chronic bronchitis

Cardiac trauma Cardiac catheterization Lumbago

Skeletal muscle trauma (severe) Electrical countershock Febrile disorder

Dermatomyositis, polymyositis Noncardiac surgery

Myopathic disorders Brain and head trauma

Muscular dystrophy, especially Duchenne Peripartum period

Extreme exercise Miscellaneous drug overdoses

Malignant hyperthermia CO poisoning

Reye syndrome Prostatic cancer

Rhabdomyolysis of any cause

Delirium tremens

Ethanol poisoning (chronic)

Abbreviation: CK-MB =creatine kinase, subunits muscle and brain.

The 4- to 8-h delay in CK-MB detection after onset of symptoms has been overcome in

part with the development of rapid assays for CK-MB isoforms (subforms). The

isoenzymes CK-MM, CK-MB, and CK-BB are dimeric molecules consisting of three

different combinations of two monomers, M and B. On its release from damaged cells,

the M monomer found in tissue CK (Mt) is acted on by an enzyme present in serum,

carboxypeptidase N, which cleaves off the C-terminal lysine. This action results in its

conversion into the M monomer found in serum CK (Ms). Newly released unmodified

CK-MtB (or CK-MB2) is enzymatically changed into CK-MsB (or CK-MB1). Because

the rate of this conversion is limited, CK-MB2 activity reflects new recent release into

the serum. By measuring MB2 activity (>1 U/L) and the MB2:MB1 ratio (>1.5),

infarction can be detected before the total level of CK-MB exceeds the normal range.

Although this method has reported early (<6 h of symptom onset) sensitivity and

specificity for AMI of 95.7 percent and 93.9 percent, respectively, technical difficulties

with the assay system have thus far limited clinical acceptance.14

Myoglobin

Myoglobin is a small (17,500 Da), heme-containing protein found in striated (skeletal)

and cardiac muscle cells. When disrupted, these cells rapidly release myoglobin into the

serum. After AMI, serum myoglobin levels begin to rise within 3 h of onset of symptoms

and are abnormally elevated in 80 to 100 percent of patients at 6 to 8 h, peak at 4 to 9 h

(see Figure 49-1), and with normal kidney function return to baseline within 24 h from

symptom onset. A false-negative result may occur if the test is performed after

myoglobin has already been cleared from the serum. False positives also abound, because

the myoglobin found in myocardium is indistinguishable from that found in skeletal

muscle. Fortunately, conditions that also result in myoglobin release usually can be

clinically diagnosed. By excluding those patients with known trauma, renal failure, or

cocaine use, one study found myoglobin's "clinical specificity" to be equivalent to that of

CK-MB and troponin.15

Troponins I and T

The troponin complex is the main regulatory protein of the thin filament of the myofibrils

that regulate the Ca2+-dependent ATP hydrolysis of actomyosin. The troponin complex

consists of three subunits: an inhibitory subunit (troponin I), a tropomyosin-binding

subunit (troponin T), and a calcium-binding subunit (troponin C). Immunoassays based

on the significant heterogeneity in amino acid sequences can detect the specific isoforms.

The cardiac isoform of troponin I is not found in skeletal muscle during any stage of

development and therefore is associated only with myocardial necrosis.

After AMI, cardiac troponin I (cTnI) and troponin T (cTnT) become elevated after

approximately 6 h, peak at 12 h, and remain elevated for 7 to 10 days. Both have a higher

specificity for myocardial necrosis than CK-MB in selected subsets of patients, such as

those presenting late in the course of AMI or those with recent surgery, a cocaine habit,

or skeletal muscle disease. Both troponins have been shown to have high sensitivity and

specificity for AMI in ED patients with chest pain and among those with possible

ischemic equivalents. Elevation of either cardiac troponin also predicts subsequent

cardiovascular complications independent of CK-MB and the ECG.16

Interpretation of troponin results in the presence of renal failure is an area of controversy.

Although only troponin T has been found in skeletal muscle biopsies of patients with

renal failure, troponins I and T are sometimes elevated in renal patients without other

evidence of cardiac disease. Further, there have been conflicting reports as to the

prognostic significance of elevated levels of either troponin in patients with renal failure.

Other Markers

Other markers of myocardial ischemia or infarction are currently being evaluated for

utility: myoglobin/carbonic anhydrase III combinations, glycogen phosphorylase BB, and

myosin light chains, to name three. In addition, markers of inflammation (e.g., C-reactive

protein), platelet activation and adhesion (e.g., P-selectin and other integrins), and cardiac

function (B-type natriuretic peptide, or BNP) are theoretically attractive as indicators of

ACS. C-reactive protein and BNP have some prognostic value in patients with possible

ACS, but their overall role in diagnosis remains to be determined.

Clinical Applications of Myocardial Marker Measurements

The current literature supports the inclusion of myocardial marker measurements in

protocols governing the ED evaluation of patients with chest pain for four distinct

purposes. The first three applications are discussed below, while the fourth use of an

accelerated marker curve is discussed later in Chap. 50.

Early Diagnosis of AMI

In those patients whose initial ECG is diagnostic for AMI, no further marker testing is

required before initiation of appropriate interventions. In patients with a nondiagnostic

ECG, AMI cannot be definitively excluded within the first few hours from symptom

onset. However, some AMI patients with nondiagnostic initial ECGs will have positive

marker tests upon ED arrival, and many more will develop positive tests during the first

few hours after presentation.

In AMI, the initial CK-MB measurement obtained upon ED arrival is elevated in about

30 to 50 percent of patients.17 By serial measures at 2- to 3-h intervals, diagnostic

increases in CK-MB can be obtained in 80 to 96 percent of AMI patients during the

initial six hours. The same principle can be applied with serial measurements of cTnI and

cTnT. Owing to its earlier release into serum after coronary artery occlusion, myoglobin

has a potential advantage over CK-MB and troponin for early diagnosis of AMI. Using a

panel of markers (myoglobin, CK-MB, and cTnI) performed upon arrival and after 3 h, it

is possible to detect over 90 percent of AMI patients.17,18

Identifying "Missed MI" Patients

Single-sample myocardial marker measurements cannot be used to exclude the diagnosis

of AMI in the ED. However, routine incorporation of marker testing into patient-care

algorithms for those patients deemed sufficiently low risk so that they are slated for

discharge without definitive AMI rule-out has been shown to identify some patients

(admitted and discharged from the ED) with unsuspected MI.19 Further, a strategy using

two CK-MB measurements drawn 3 h apart for patients selected for discharge will

identify ACS patients. Although these strategies have not been validated, these and

several other studies suggest that ED patients slated for discharge after evaluation for

chest pain and ischemic equivalents may benefit from at least one myocardial marker

measurement.

Early Risk Stratification

Increased use of newer anti-ischemic therapies (angiographic interventions and

antiplatelet and antithrombotic drugs), although improving outcomes, carries risks and

high costs. Thus, a selective approach to their use is required. Several investigations have

suggested that markers of myocardial injury can be used successfully in the ED to rapidly

identify those patients most likely to benefit from a more aggressive approach. Numerous

investigations have demonstrated that early ED testing of CK-MB, myoglobin, troponin

T, or troponin I yields clinically useful prognostic data for adverse events, and that

simultaneous testing of troponin and CK-MB may identify additional high-risk patients

as opposed to testing for one marker.

After reviewing this evidence, the Joint European Society of Cardiology/American

College of Cardiology Committee for the Redefinition of MI reported in 2000 that there

is "no discernible threshold below which an elevated value for cardiac troponin would be

deemed harmless. All elevated values are associated with a worsened prognosis."20

Unfortunately, the threshold values historically suggested by the manufacturers of

laboratory assays for CK-MB, troponin, and other myocardial markers have been

determined based on the traditional definition of MI and are therefore inadequate for risk

stratification. Recognizing this, the joint committee went on to recommend that new

threshold values for each marker be established at the 99th percentile of the values for an

appropriate reference control (normal) group. Because this recommendation has not been

uniformly accepted and implemented by hospital laboratories, to optimally use the

prognostic information offered by ED myocardial marker testing, emergency physicians

should be aware of the appropriate threshold values for risk stratification and for MI

diagnosis in their individual institutions.

Point of Care Testing

With current monoclonal antibody technology, qualitative and quantitative cardiac

marker panels for CK-MB, troponin I and T, and myoglobin are available for use at the

bedside. A quantitative assay for BNP has also been developed for bedside use. Most

point of care cardiac marker testing panels provide results within 15 to 20 min, generally

faster than most hospital laboratories. Rapid bedside results would be theoretically useful

when the results would affect early therapy (e.g., initiation of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa

inhibitors) or alter disposition (e.g., primary percutaneous coronary intervention instead

of medical therapy). Rapid bedside cardiac marker assessment may also be useful when

the initial ECG is rendered difficult to evaluate due to preexisting ventricular conduction

blocks or chronic ventricular pacing. The overall value of rapid bedside cardiac marker

detection remains to be determined.

Computerized Decision Aids

To facilitate more accurate disposition decisions and thereby reduce mounting health care

costs, several investigators tried to develop computerized decision aids or computerbased triage protocols for ED patients with chest pain. Unfortunately, no simple

algorithm has proven both safe and effective for ED-based triage of acute chest pain

patients.

Other methods, such as multivariate analysis and artificial neural networks, have been

used to develop predictive instruments. Actual clinical use of the most studied of these

decision aids, the Acute Cardiac Ischemia Time-Insensitive Predictive Instrument (ACITIPI), resulted in a decrease of 26 percent in cardiac care unit admissions and an increase

of 47 percent in ED discharges to home without increasing the number of missed AMIs.

The ACI-TIPI uses a logistic regression formula that evaluates the probability of acute

ischemia by analyzing specific history and ECG characteristics. The instrument has been

incorporated into computerized ECG machines in the ED, and the result is printed

directly onto the ECG tracing.21

An artificial neural network is a nonlinear statistical program that can recognize complex

patterns and maintain accuracy even when some of the required data are missing. This

theoretically enables users to apply the tool in real time even when they do not have all of

the required data elements called for in the stratification model. The accuracy of one such

tool was hypothetically tested in 2204 patients. The network demonstrated a significant

improvement over physician decision making, with a sensitivity of 94.5 percent and a

specificity of 95.5 percent for the diagnosis of AMI.22 A more recent instrument has

been developed to include diagnoses in the overall spectrum of myocardial ischemia.23

Despite the demonstration of diagnostic superiority and improved cost-effectiveness

compared with physician decision making alone, these instruments have not been

embraced by clinicians. Among the barriers cited to acceptance of decision aids into

clinical practice are medicolegal concerns, slow adoption of new technology, and

physicians' fear of losing autonomy. Thus, additional work in this area must now focus

on physician behavior and the interface between human and machine.

Approach to Low Probability of Ischemia

Patients identified as having ST-segment elevation MI or recognized as having a high

potential for an ACS are addressed as discussed in Chap. 50. Other patients may be

classified as having a very low, low, or moderate probability of acute ischemia based on

clinical information available within the initial hours of their ED visit. Many

investigators now recommend the use of a five-subgroup classification scheme for this

initial risk stratification (Table 49-3). However, there is still no consensus regarding

optimal risk subgroupings, criteria for such stratification, or agreement as to the most

effective evaluation and treatment protocols after initial categorization. There is

consensus on two issues regarding lower-risk patients: history alone is inadequate to

exclude the presence of acute ischemia, and the goal should always be "zero tolerance"

for missed AMI. It is also accepted that some form of systematic approach based on

objective data is required to accurately and efficiently pursue further diagnostic

evaluation to an appropriate end point in each patient (Figure 49-2).10

Table 49-3 Prognosis-Based Classification System for ED Chest Pain Patients*

I. Acute myocardial infarction: immediate revascularization candidate

II. Probable acute ischemia: high risk for adverse events

Any of the following

Evidence of clinical instability (i.e., pulmonary edema, hypotension, arrhythmia)

Ongoing pain thought to be ischemic

Pain at rest associated with ischemic ECG changes

One or more positive myocardial marker measurements

Positive perfusion imaging study

III. Possible acute ischemia: intermediate risk for adverse events

History suggestive of ischemia with any of the following

Rest pain, now resolved

New onset of pain

Crescendo pattern of pain

Ischemic pattern on ECG not associated with pain

IV. A. Probably not ischemia: low risk for adverse events

Requires all of the following

History not strongly suggestive of ischemia

ECG normal, unchanged from previous, or nonspecific changes

Negative myocardial marker measurement

B. Stable angina pectoris: low risk for adverse events

Requires all of the following

More than 2 wk of unchanged symptom pattern or longstanding symptoms with only

mild change in exertional pain threshold

ECG normal, unchanged from previous, or nonspecific changes

Negative initial myocardial marker measurement

V. Definitely not ischemia: very low risk for adverse events

Requires all of the following

Clear objective evidence of non-ischemic symptom etiology

ECG normal, unchanged from previous, or nonspecific changes

Negative initial myocardial marker mesurement

*Authors' analyses from multiple sources.

Abbreviation: ECG = electrocardiogram.

Fig. 49-2.

Algorithm for risk-based decision-making. Abbreviation: PCI = percutaneous coronary

intervention.

Interpretation of the many diagnostic tests now available to assist in diagnosis and risk

stratification of ED patients with possible ACS increasingly has become the

responsibility of the emergency physician.

Common Diagnostic Tests Used in Emergency Cardiac Care

ECG-Based (Standard) Exercise Stress Testing

In the ED setting, exercise testing has been recommended for patients applied as the final

component of a chest pain observation protocol after the exclusion of AMI or, in selected

low-risk patients, soon after presentation as an alternative to an extended observation

period.24

Many variations exist in the equipment, procedures, and interpretive algorithms used.

Treadmills are used more commonly in the United States, because many patients cannot

reach the desired point of maximum oxygen uptake by using cycles or other devices. In

appropriate patients, stress testing is safe: dysrhythmia, AMI, and death occur at rates of

4.8, 3.6, and 0.5 per 10,000 tests, respectively.

No consensus exists on the preferred protocol, although the Bruce protocol is the most

common and best studied. Depending on the protocol followed, exercise is terminated

when the subject reaches a predetermined percentage of predicted maximum heart rate

(i.e., 85 percent) or when another defined end point is reached. The most commonly used

definition of a positive exercise test result from an ECG standpoint is greater than or

equal to 1 mm of horizontal or downsloping ST-segment depression or elevation for at

least 60 to 80 ms after the end of the QRS complex.

Exercise stress testing may be contraindicated for various reasons (Table 49-4). If the

patient has physical limitations preventing exercise but no other contraindications, a

pharmacologic stress test using a chronotropic drug (i.e., dobutamine) may be

appropriate. Exercise testing may not be safe for patients at high risk for acute ischemia

or those with other uncontrolled cardiovascular or pulmonary pathologies. Further,

patients with an abnormal baseline ECG, such as those with left ventricular hypertrophy,

bundle-branch block, or digoxin effect, are less likely to benefit from standard exercise

testing owing to difficulties in interpretation of exercise-induced ECG changes.

Table 49-4 Contraindications to Exercise Testing

Absolute

Acute myocardial infarction (within 2 d)

Unstable angina not previously stabilized by medical therapy

Uncontrolled cardiac dysrhythmias causing symptoms or hemodynamic compromise

Symptomatic severe aortic stenosis

Uncontrolled symptomatic heart failure

Acute pulmonary embolus or pulmonary infarction

Acute myocarditis or pericarditis

Acute aortic dissection

Relative*

Left main coronary stenosis

Moderate stenotic valvular heart disease

Electrolyte abnormalities

Severe arterial hypertension

Tachydysrhythmias or bradydysrhythmias

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and other forms of outflow tract obstruction

Mental or physical impairment leading to inability to exercise adequately

High-degree atrioventricular block

*Relative contraindications can be superseded if the benefits of exercise outweigh the

risks.

In the absence of definitive evidence, the AHA committee suggests systolic blood

pressure of >200 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure of >110 mm Hg.

Source: Fletcher GF, Balady G, Froelicher VF, et al: Exercise standards: A statement for

healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association Writing Group. Special

Report. Circulation 91:580, 1995.

The clinical utility of ED stress testing depends on the test result's ability to modify the

pretest probability of the diagnosis and to change treatment and disposition. Emergency

department stress testing is particularly difficult to quantify, because test sensitivity and

specificity are greatly influenced by the population being tested. As the pretest

probability of significant CAD increases, the likelihood of a false-negative test also

increases. Conversely, when a population with a very low pretest probability of disease is

tested, the likelihood of a false-positive result increases. Therefore, based on current data,

diagnostic stress testing is recommended for patients with a low pretest probability of

CAD but is unlikely to be helpful in those at very low risk (<5 percent) or moderate to

high risk (>30 percent). The pretest probability of disease can be determined

semiquantitatively based on demographic, historical, and ECG data with any of the

validated decision aids previously described.

Emergency department stress testing may be of further value when applied to a broader

range of patients, if the goal of testing is to predict prognosis rather than diagnosis. Many

studies have confirmed that ED stress testing of selected patients can reliably predict

short-term (<1 y) prognosis.

Myocardial Imaging

Echocardiography

Advantages of echocardiography include its noninvasive, dynamic nature, its lack of

radioactive materials, and that even sophisticated machines can be used at the bedside in

the ED.24 Further, it can assess the potential for other etiologies of chest pain, including

aortic dissection, pericardial pathology, valvular disease, and possibly PE (see Chap. 61).

The value of echocardiography in evaluating ischemic heart disease is based largely on

the experimental finding in animal and human studies that acute myocardial ischemia

reliably and rapidly results in observable wall motion abnormalities. Thus, theoretically, a

normal echocardiogram during chest pain should exclude the presence of ischemia.

Unfortunately, this finding is limited by several factors. Because the effects of adjacent

wall segments commonly lead to false-positive and false-negative interpretations of wall

motion abnormalities, systolic wall thickening is used as a more specific indicator of

ischemia. However, detection of wall-thickening abnormalities is highly dependent on

imaging technique and interpretative skills, with up to 10 percent of tests being

technically inadequate. Further, the echocardiogram cannot distinguish between

myocardial ischemia and acute infarction, cannot reliably detect subendocardial ischemia,

and may be falsely interpreted as positive in the presence of several conditions

(conduction disturbances, volume overload, heart surgery, or trauma). Timing of the test

relative to the onset of symptoms is critical, because transient wall motion abnormalities

may resolve within minutes of an ischemic episode. Indeed, one prospective study of ED

patients found that resting echo within 12 h of ED arrival does not provide additional

predictive value for MI over myocardial markers alone. Thus, a normal resting

echocardiogram in the ED should not be used to exclude ACS.25

Stress echocardiography combines a standard ECG stress test with cardiac imaging at rest

and after exercise (or during pharmacologically induced tachycardia). Thus, it is superior

to standard stress testing. When evaluated among low-risk ED patients, three studies have

reported negative predictive values for subsequent cardiac events to be 97 to 100 percent,

comparable to that of stress testing using nuclear imaging techniques.25

Contrast echocardiography using physiologically safe microbubbles is a newer technique

that holds future promise but is not routinely used in clinical practice. Studies have

suggested that this technique significantly improves the detection of regional wall motion

abnormalities and wall thickening as compared with conventional sonography. In one

study, 28 percent of standard stress echoes performed were inconclusive due to

difficulties in interpretation but were decisively normal or abnormal with the use of

contrast. In the future, contrast echocardiography may be able to directly assess coronary

vessel patency, even at the microvascular level, with sensitivity similar to or greater than

that of nuclear perfusion imaging.25

Perfusion Imaging

Myocardial perfusion imaging uses an intravenously injected radioactive tracer that is

distributed throughout the coronary circulation (see Chap. 61). Local myocardial uptake

and, subsequently, myocardial imaging therefore are dependent on adequate regional

coronary flow and myocardial cell integrity. Tracer uptake occurs in direct proportion to

regional myocardial blood flow.24

Thallium 201 is the oldest and most studied tracer in common use today. Thallium is

rapidly redistributed after initial uptake. The image represents blood flow at the moment

of imaging. Areas of positive uptake reflect adequate coronary flow and viable

myocardium, whereas areas without uptake represent infarcted or ischemic myocardium.

On repeat imaging several hours later, continued lack of perfusion ("irreversible defect")

indicates an area of infarction, whereas areas with tracer uptake only on delayed images

("reversible defect") represent previously ischemic myocardium. Combined with

conventional ECG-based stress testing, thallium imaging offers improved sensitivity and

specificity for detection of significant CAD over ECG-based testing alone. Further,

thallium testing (or other perfusion imaging) is likely to be of value in patients who

would not otherwise benefit from stress testing due to a confounding or potentially

masking abnormal baseline ECG.

There are several limitations of thallium testing. Imaging must be performed soon after

injection, making it impractical for use in patients with ongoing chest pain. Moreover,

because of a long half-life, the injected dose of thallium must be kept low to avoid

excessive radiation exposure. This and other properties of the tracer result in a relatively

poor image quality and the frequent occurrence of artifactual perfusion defects (false

positives) due to overlying tissue attenuation. This is particularly common in women and

obese patients. Due to these limitations and the lack of ED-based efficacy studies,

thallium-201 imaging alone is not an ideal agent for use in the ED.

Myocardial perfusion imaging using technetium 99m (99mTc)-labeled agents such as

sestamibi offers advantages over thallium for ED use. Because the half-life of 99mTc is

much shorter than that of thallium (6 vs. 73 h), a larger dosage can be injected without

harm to the patient. This results in the superior image quality, decreased tissue

attenuation-related artifacts, and higher specificity for sestamibi imaging. Newer 99mTc

agents being introduced continue to improve image quality. In addition, in contrast to

thallium, the initial distribution of 99mTc agents is stable for several hours. Therefore,

accurate imaging can occur up to 3 h after injection. The image represents the blood flow

at the moment of injection. By using "gated" image acquisition technology, sestamibi

scanning can yield an accurate estimation of ejection fraction. As with thallium, resting

and stress (exercise or pharmacologic) images can be compared to yield additional data.

Dual isotope stress testing using thallium and sestamibi is an increasingly common

component of ED ACS evaluation protocols. In this technique, a resting thallium scan is

first performed. Those patients without resting defects can then immediately undergo

stress testing with sestamibi imaging, thereby avoiding the delay usually required for

isotope "washout" in single isotope techniques. In a recent prospective study, a strategy

using this method reliably identified or excluded ACS among 1775 low-risk ED

patients.26

The use of electron-beam computed tomography for the detection of coronary artery

calcification has shown promise as a noninvasive alternative for the diagnosis of CAD. A

"calcium score" is generated and is directly related to the likelihood of having CAD

(within a given demographic group). Electron-beam computed tomography has a number

of limitations. It cannot identify the minority of plaques that do not contain calcium, and

it does not demonstrate microvascular or vasospastic disease. Although this technique

shows promise as an alternative to the previously discussed imaging techniques, its role

in ED evaluation remains undefined.27

Low-Risk Patient Protocols

Inpatient Admission

In settings where extended observation and definitive diagnostic testing are not available

in the ED, all patients whose presentations suggest a reasonable plausibility of an acute

ischemic event should be admitted to an inpatient bed. Once the need for inpatient

admission has been determined, further stratification based on assessment of the patient's

short-term risk of morbidity or mortality can be made based on the patient's history and

physical examination, initial ECG, and early myocardial marker measurement. Patients

with a prior history of CAD, evidence of congestive heart failure on physical

examination, recurrent chest pain in the ED, or new or presumed new ischemic ECG

changes are at higher short-term risk and may be more appropriately managed in an

intermediate-care (step-down) unit. Conversely, patients whose initial ED ECG is normal

or unchanged from a previous ECG have a very low risk of adverse events and can safely

be evaluated on a monitored floor or telemetry bed. Those with nonspecific changes on

the initial ECG represent an intermediate-risk group. A single myocardial marker

measurement soon after ED presentation also can identify those patients at greater risk

from among those with atypical presentations.

ED Observation/Monitoring

In 1991, the Multicenter Chest Pain Study Group reported that the diagnosis of infarction

could have been safely excluded within a 12-h observation period among a subgroup of

patients admitted for chest pain but identified at presentation as having a low probability

of AMI.28 The investigators also suggested routine predischarge stress testing of these

patients to reduce the risk of discharging patients with unstable coronary syndromes

prematurely. Gibler and colleagues later refined this approach.29 Patients with symptoms

consistent but weakly suggestive of acute ischemia were observed for 9 h with

continuous 12-lead ST-segment ECG monitoring and serial CK-MB testing at 0, 3, 6, and

9 h after presentation. Those who completed a negative 9-h evaluation subsequently

underwent echocardiography followed by graded exercise stress testing in the ED before

discharge. With this approach, 82.1 percent of patients were released home from the

cardiac evaluation unit.29

Although there is no consensus on the best approach, many studies have documented

clinical safety and efficacy and cost savings associated with use of an ED-based Cardiac

Evaluation Unit protocol compared with traditional inpatient admission, and their use has

continued to expand.

Normal serial ECGs and myocardial marker measurements do not preclude the presence

of other ACSs (i.e., unstable angina), which may still put the patient at high risk for a

subsequent adverse event. Therefore, further evaluation is generally recommended before

discharge (Figure 49-3). The various forms of stress testing (with or without myocardial

imaging) currently offer the best noninvasive method to predict the presence of CAD and

assess prognosis. Over the past decade, numerous published reports have confirmed the

safety, clinical utility, and cost-effectiveness of various versions of this accelerated MI

rule-out/early risk stratification concept, and this strategy has been incorporated into the

ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for the management of patients with unstable angina

and non-ST-segment elevation MI.10

Fig. 49-3.

Alternative risk stratification protocols for low-risk patients.

Disposition

The assessment of acute chest pain patients is difficult, and the processes and approaches

discussed in this chapter are not perfect. This is best illustrated in AMI, where the "miss"

rate for AMI in patients evaluated in the emergency department using history, physical

examination, ECG, and serum markers is currently about 2 percent; these patients were

discharged and upon follow-up were determined to have sustained an AMI. The good

news is that the use of serial marker measurements, evaluation or observation units,

myocardial imaging studies, and stress testing has the potential to reduce this "missedMI" rate to close to zero. Unfortunately, UA sometimes remains an elusive and difficult

diagnosis. There is little information on the ED "miss rate" for the important diagnoses of

aortic dissection and pulmonary embolism. Despite advances in serum marker technology

and imaging studies, the physician must still exercise clinical judgment when evaluating

acute chest pain patients. To make the best possible decisions, clinicians should collect

adequate information first before exercising their judgment. The ability to make good

decisions when faced with incomplete or uncertain information is an important skill.

The disposition of patients who have a defined diagnosis as the cause of their chest pain

is relatively straightforward. Those patients without a specific diagnosis—so-called

atypical chest pain—pose more of a problem. A useful principle in these patients with

atypical chest pain is the use of a composite picture to assign patients to a category where

the potential for ACS or other serious causes of chest pain is vanishingly small, and such

patients can be safely discharged. These patients often have pain described as sharp; well

localized; reproducible by position, breathing, or palpation; and have no prior diagnosis

of angina or AMI. The pretest probability of ACS or other serious conditions is so low

that ancillary testing is usually not indicated and patients can be discharged after the

history and physical examination. Conversely, patients with unexplained visceral chest

pain should not be discharged unless potentially serious conditions have been excluded

using appropriate ancillary testing.

Discharged patients should receive appropriate instructions regarding medications and

follow-up directions. They should also be instructed to seek prompt attention or return for

recurrent or worsening chest pain or other serious symptoms. Some institutions have

instituted chest pain clinics to ensure that patients receive appropriate follow-up after

their discharge from the ED.

References

1. Lee TH, Goldman L: Evaluation of the patient with acute chest pain. New Engl J Med

342:1187, 2000. [PMID: 10770985]

2. Panju AA, Hemmelgarn BR, Guyatt GH, Simel DL: Is this patient having a myocardial

infarction? JAMA 280:1256, 1998. [PMID: 9786377]

3. Gupta M, Tabas JA, Kohn MA: Presenting complaint among patients with myocardial

infarction who present to an urban, public hospital emergency department. Ann Emerg

Med 40:180, 2002. [PMID: 12140497]

4. Canto JG, Shlipak MG, Rogers WJ, et al: Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and

mortality among patients with myocardial infarction presenting without chest pain.

JAMA 283;3227, 2002.

5. Douglas PS, Ginsburg GS: The evaluation of chest pain in women. New Engl J Med

334:1311, 1996. [PMID: 8609950]

6. Wicki J, Perneger TV, Junod AF, et al: Assessing clinical probability of pulmonary

embolism in the emergency ward. Arch Intern Med 161:92, 2001. [PMID: 11146703]

7. Klompas M: Does this patient have an acute thoracic aortic dissection? JAMA

287:2262, 2002. [PMID: 11980527]

8. Wulsin L, Liu T, Storrow A, et al: A randomized, controlled trial of panic disorder

treatment initiation in an emergency department chest pain center. Ann Emerg Med

39:139, 2002. [PMID: 11823767]

9. Fleet RP, Dupuis G, Marchand A, et al: Panic disorder in ED chest pain patients:

Prevalence, comorbidity, suicidal ideation and physician recognition. Am J Med 101:371,

1996. [PMID: 8873507]

10. Braumwald E, Antman EM, Beasley JW, et al: ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for

the management of patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation

myocardial infarction: A report of the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines

(Committee on the Management of Patients with Unstable Angina), 2002. Available at

http://www.acc.org/clinical/guidelines/unstable/unstable.pdf.

11. Zimetbaum PJ, Josephson ME: Use of the electrocardiogram in acute myo-cardial

infarction. New Engl J Med 348:933, 2003. [PMID: 12621138]

12. Silber SH, Leo PJ, Katapadi M: Serial electrocardiograms for chest pain patients with

initial nondiagnostic electrocardiograms: Implications for thrombolytic therapy. Acad

Emerg Med 3:147, 1996. [PMID: 8808376]

13. Selker HP, Zalenski RJ, Antman EM, et al: An evaluation of technologies for

identification of acute cardiac ischemia in the emergency department: A report from the

National Heart Attack Alert Program Working Group. Ann Emerg Med 29:13, 1997.

[PMID: 8998086]

14. Puleo PR, Meyer D, Wathen C, et al: Use of a rapid assay of subforms of creatine

kinase-MB to diagnose or rule out acute myocardial infarction. New Engl J Med 331:561,

1994. [PMID: 7702648]

15. Green GB, Skarbek-Borosky GW, Chan DW, et al: Myoglobin for early risk

stratification of ED patients with possible myocardial ischemia. Acad Emerg Med 7:625,

2000. [PMID: 10905641]

16. Green GB, Li DJ, Bessman ES, et al: The prognostic significance of troponin I and

troponin T. Acad Emerg Med 5:758, 1998. [PMID: 9715236]

17. Malasky BR, Alpert JS: Diagnosis of myocardial injury by biochemical markers:

Problems and promises. Cardiol Rev 10:306, 2002. [PMID: 12215194]

18. Fesmire FM: Improved identification of acute coronary syndromes with delta cardiac

serum marker measurements during emergency department evaluation of chest pain

patients. Cardiovasc Toxicol 1:117, 2001. [PMID: 12213983]

19. Green GB, Hansen KW, Chan DW, et al: Potential utility of a rapid CK-MB assay in

evaluating emergency department patients with possible myocardial infarction. Ann

Emerg Med 20:954, 1991. [PMID: 1877780]

20. Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, et al: Myocardial infarction redefined – A

consensus document of the Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of

Cardiology Committee for the Redefinition of MI. J Am Coll Cardiol 36:959, 2000.

[PMID: 10987628]

21. Selker HP, Beschansky JR, Griffith JL, et al: Use of the Acute Cardiac Ischemia

Time-Insensitive Predictive Instrument (ACI-TIPI) to assist with triage of patients with

chest pain or other symptoms suggestive of acute cardiac ischemia. Ann Intern Med

129:845, 1998. [PMID: 9867725]

22. Baxt WG, Shofer FS, Sites FD, Hollander JE: A neural computational aid to the

diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. Ann Emerg Med 39:366, 2002. [PMID:

11919522]

23. Baxt WG, Shofer FS, Sites FD, Hollander JE: A neural network aid for the early

diagnosis of cardiac ischemia in patients presenting to the ED with chest pain. Ann

Emerg Med 40:575, 2002. [PMID: 12447333]

24. Mather PJ, Shah R: Echocardiography, nuclear scintigraphy, and stress testing in the

emergency department evaluation of acute coronary syndrome. Emerg Med Clin North

Am 19:339, 2001. [PMID: 11373982]

25. Selker HP, Zalenski RJ, Antman EM, et al: Echocardiogram: In an evaluation of

technologies for identification of acute cardiac ischemia in the emergency department: A

report from a National Heart Attack Alert Program Working Group. Ann Emerg Med

29:69, 1997.

26. Fesmire FM, Hughes AD, Stout PK, et al: Selective dual nuclear scanning in low-risk

patients with chest pain to reliably identify and exclude acute coronary syndromes. Ann

Emerg Med 38:207, 2001. [PMID: 11524638]

27. Georgiu D, Budoff MJ, Kaufer E, et al: Screening patients with chest pain in the ED

using electron bean tomography: A follow-up study. J Am Coll Cardiol 38:105, 2001.

28. Lee TH, Juarez G, Cook F, et al: Ruling out acute myocardial infarction: A

prospective multicenter validation of a 12-hour strategy for patients at low risk. New

Engl J Med 324:1239, 1991. [PMID: 2014037]

29. Gibler WB, Runyon JP, Levy RC, et al: A rapid diagnostic and treatment center for

patients with chest pain in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 25:1, 1995.

[PMID: 7802357]

30. Amsterdam EA, Kirk JD, Diercks DB, et al: Immediate exercise testing to evaluate

low-risk patients presenting to the emergency department with chest pain. J Am Coll

Cardiol 40:251, 2002. [PMID: 12106928]

31. Tatum JL, Jesse RL, Kantos MC, et al: Comprehensive strategy for the evaluation and

triage of the chest pain patient. Ann Emerg Med 29:166, 1997.

Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies. All rights reserved.

Privacy Notice. Any use is subject to the Terms of Use and Notice.