* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download PDF

Dissociative identity disorder wikipedia , lookup

Conversion disorder wikipedia , lookup

Classification of mental disorders wikipedia , lookup

Political abuse of psychiatry in Russia wikipedia , lookup

History of psychosurgery in the United Kingdom wikipedia , lookup

Child psychopathology wikipedia , lookup

Political abuse of psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Bipolar II disorder wikipedia , lookup

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Emergency psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Abnormal psychology wikipedia , lookup

Death of Dan Markingson wikipedia , lookup

History of psychiatric institutions wikipedia , lookup

History of psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

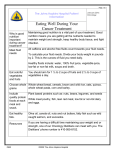

Hopkins THE NEWSLETTER SPRING 2013 O F T H E J O H N S H O P K I N S D E PA RT M E N T O F P S Y C H I AT RY A N D B E H AV I O R A L S C I E N C E S ? “Because psychiatrists examine mental life, we’re often more quickly able to detect delirium,” says Karin Neufeld, who’s also president-elect of the American Delirium Society. A humbling experience John Crowder,* 77, a retired architect, was his bright, goodnatured self, even entering a Pennsylvania hospital for an hour’s back surgery under standard general anesthesia. He did well in recovery and was wheeled to his hospital room, dozing until morning. Then things unraveled. Crowder didn’t know where he was. He told his wife to feed the rabbit in the room. He was anxious, convinced his roommate was a terrorist. Later transferred to inpatient rehab, Crowder remained confused for several weeks. Once home again, he refused to walk. He was uncharacteristically unfocused and glum for the six months it took to resemble his presurgery self. He calls the experience “one of the most humbling of my life.” From a recent Psychiatry Grand Rounds * name and details changed for privacy. Demystifying Delirium R “ oughly 40 percent of inpatients at major medical centers will be delirious at some point in their stay,” Karin Neufeld told a recent gathering of fellow Johns Hopkins psychiatry faculty. “If they’re on ventilators in the ICU, that can jump to 85 percent.” Delirium is a hospital bane, an unwelcome visitor calling reliably on the very ill or frail. And it can harm. In adults, the syndrome is tied to higher mortality and longer time in the hospital (see box, left). Yet common and damaging as it can sometimes be, “delirium remains under-recognized and understudied,” Neufeld says. So she and colleagues are among a band of nationwide movers and shakers bent on correcting that. Neufeld, who directs general hospital psychiatry, visits bedsides of three medical or psychiatric patients a day, on average, to assess suspected delirium and consult on therapy. That puts her well in position to see where the clinical gaps lie. It’s not uncommon in hospitals, for example, for staff to overlook “quiet” or hypoactive delirium or mistake it for depression, she says, or to find agitated delirium simply called psychosis. Neufeld’s most recent work sheds light on the condition’s nature and its impact. In a new study, researchers followed about 100 fairly robust patients over age 70 undergoing hip surgery, assessing them before it, just afterward and at hospital discharge. Two results stood out. One was in the recovery room, where staff typically don’t look for delirium, since—the thinking goes—general anesthesia makes everyone unfocused and disoriented. But the study showed that nearly half of patients had frank, DSM-matching delirium. It faded quickly in some, but lasted three days in an equal number later moved to hospital beds. The other result confirms others’ findings: Delirium increases the burden of frailty in older people. “Our elders who were delirious in recovery,” she says, “were nine times as likely to go to rehab or a nursing home.” What’s the culprit in all this? Is it length of surgery? Anesthesia? Surgical sedatives? “Our work suggests the depth of sedation plays a part, but that needs more study,” says Neufeld. “We have a lot to learn.” n For information: 410-502-1169 A Different Delirium “I wanted to see how we stand, clinically, at spotting delirium in children,” says child psychiatrist Patrick Kelly. “And the answer is, really bad.” While the necessity of treating delirium in adults is catching on (story, left), that hasn’t yet hit home in pediatrics nationwide, Kelly says. As in adults, there are problems of recognition. “We’ll get hospital calls to evaluate kids who suddenly become atypically anxious or aggressive,” he says. It’s fairly easy to spot a child in the PICU who says—this is an actual case—there’s a purple watermelon on my bed. But he and colleague Emily Frosh note that usually, the phenomenon is more subtle in kids than adults. “They come across as quiet and cute, when, in fact, they have no idea what’s going on around them. The delirium is missed entirely,” says Kelly. So he and Frosh began documenting suspected instances when delirium was missed. A just-published study describes their review of records of 515 children referred, over eight years, for inpatient psychiatric consultation in The Johns Hopkins Hospital. Attention was paid to records with a diagnosis of delirium—or something close to it. Also, the two sifted computerized pediatric discharge records of roughly 64,000 kids during the same period. The results? Pediatricians listed delirium only a tiny fraction of the time as a reason for sending children for a consult. And for the thousands of kids who’d passed through the hospital apparently without needing any such evaluation, the records say that only 0.1 percent of them had spent some time delirious. “We know that’s way out of line,” says Kelly. What accounts most for the dramatic shortfall, he believes, “is not realizing how serious delirium is.” Not infrequently, it carries lingering cognitive effects and more serious implications for overall health. It isn’t a benign process “that just happens and is done with,” Kelly says. “What hospitals need most right now is consciousnessraising.” n For information: 410-955-7874 FROM THE LAB Stress: Can It Bring More Than Teen Angst? T here’s a reason that Minae Niwa and Hanna Jaaro-Peled picked mice age 5 to 8 weeks old for their recent study: The rodents are teenagers. It’s a tender age for mice or humans and one increasingly eyed by researchers as key to pathology that schizophrenia, major depression and bipolar disorder likely have in common. Recently, a mouse study by Niwa and JaaroPeled’s team, under mentor Akira Sawa, modeled current thought on triggers of those illnesses—mostly young adult-onset neuropsychiatric disorders. The results offer a way that stress, at a certain age and vulnerability, may trip major psychiatric disease. A body of science confirms that teenage mice and humans respond similarly to stress. The HPA axis, the brain’s key stress pathway, goes into overdrive, releasing cortisol. And at puberty, some studies say, that hormone’s effect in man and mouse appears more potent; brains stay longer in “red alert” mode after each stressor du jour has faded. Still other research suggests some link between cortisol and brain levels of dopamine, a neurotransmitter active in cognition, learning, mood and reward. Dopamine goes awry in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression. But how, asked the Johns Hopkins group, to tie the threads together? Niwa and Jaaro-Peled’s new study simulated the proposed human risks for illness: Test mice (and controls) were teenagers. The mice also had moderate gene-based chances for a troubled brain: They carried a mutation from a human family with depression tinged with psychosis. Finally, test mice in the study lived three weeks on their own, a situation exposing each animal to stress roughly as intense, say, as what teens face the first days of For neuroscientists Hanna Jaaro-Peled and Minae Niwa, finely tailoring mouse models of psychiatric disease helps show how small shifts in brain chemistry change the very circuits that oversee thinking and behavior. high school—a “suboptimal” stressor, says Sawa. The results were telling. Carrying the abnormal gene had little effect on the mice unless they were also stressed. Then they became more readily hyperactive or displayed other behaviors that signal brain disorder. On a biological level, there was more. The stress-plus mutation mice showed high cortisol levels and a significant drop in dopamine. Was cortisol at work in the drop? An added experimental step said yes. Injecting mice with an agent that blocks cortisol activity righted dopamine levels. It also corrected mouse behavior. The “take-home” from this, Sawa says, “seems to be that during adolescence, if there’s adequate genetic risk, stress can change biology and behavior in ways that we associate with neuropsychiatric disease.” Perhaps more important in the long run were results that suggest therapy targets. The team found that cortisol affects key, dopamine-rich nerve paths between the midbrain and the prefrontal cortex. The “ventral tegmental area” is a vulnerable brain tract that rules concentration, for example, and other things cognitive that neuropsychiatric disease harms. The second find suggests that cortisol’s effect at puberty may last. Mice returned to group life still behaved abnormally months later. The underlying biology suggests why: High cortisol clamps epigenetic “governors” on key dopamine genes. “This study made me think prevention. It’s certainly not foolish to be more vigilant with our teenagers who are genetically vulnerable to psychiatric disorders,” says Sawa. “My gut feeling is that environmental stressors—social ones especially—are more important than the genetic in letting mental illness appear.” n For information: 410-955-4726 CLINICAL RESEARCH Seeking a Stimulating Solution for Alzheimer’s T his past November, Johns Hopkins surgeons eased a fine electrode into the brain of a patient in early-stage Alzheimer’s disease, down to the fornix, a site hard-hit by the illness. Far from being routine therapy, the operation was the first in this country to explore deep brain stimulation (DBS) for Alzheimer’s. Its outcome shores up work to see if the technique might stop or slow patients’ decline into dementia. This new trial follows a preliminary study in Toronto, Canada, in which surgeons implanted the stimulating devices in six AD patients. Researchers then found that under the pulsed mild current that DBS creates, those in the study—all in early stages of the disorder—showed increases in glucose metabolism that mark heightened activity in known memory circuits. The effect lasted over the 13-month test period. Most patients with AD would normally see decreases in that length of time. “Recent failures of the large trials of drugs that target beta-amyloid plaques, a prime AD suspect in the brain, have sharpened our need for alternative strategies,” says psychiatrist Paul Rosenberg, site director of the new work at Johns Hopkins. “Trying to enhance brain function by mechanical means is a whole new avenue to explore.” Patients undergoing DBS carry a pacemaker-like stimulator implanted just under the skin. An electrode extends from it, painlessly, to the brain. The arrangement isn’t new: DBS is well-established for Parkinson’s disease. And it’s under study for depression and chronic pain. In this newest work, some 40 Alzheimer’s patients will receive DBS over the next year or so at Hopkins and four other North American medical centers—all part of the ADvance Study co-led by Johns Hopkins psychiatrist Constantine Lyketsos and neurologist Andres Lozano at the University of Toronto. Only those impaired mildly enough to still be able to make informed decisions can participate. n For information: 410-550-4258 INSIGHT: Q & A with ROBERT FINDLING Pediatric Bipolar Disorders: Seeking the Right Child, the Right Time “You’ve got this vague, fuzzy thing behind an opaque screen. How do you figure out what to do with it?” That’s child psychiatrist Robert Findling’s take on what clinicians face in pediatric bipolar disorders. As new director of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Findling brings broad expertise on those illnesses and others to Johns Hopkins. His Clinical Manual of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology is in its second edition. Cognitive-Behavior Therapy for Children and Adolescents—he’s a co-author—is just out. He’s published on pediatric psychotic disorders and juvenile schizophrenia. But Findling’s prime area is pediatric bipolar illness, a condition whose unspecific symptoms hamper diagnosis, especially in young children. That alone encourages controversy—sometimes from clinicians, but more from a public a bit too ready to blame symptoms on bad parenting or kids being kids. “There’s been too much heat, not enough light,” Findling says. So he takes refuge in sound research. For the past seven years, he has coheaded the Longitudinal Assessment of Manic Symptoms (LAMS), a NIMHfunded study that’s followed some 700 children whose elevated irritability, sudden mood changes and periods of more than kid-typical giddiness suggest bipolarity. The research—Findling now directs it from Johns Hopkins—aims to sort out what the symptoms mean. Do they mark a distinct childhood illness? Who comes out OK? symptoms. So we follow the children and, ideally, the study clarifies the disorder, tells us who has it—and where it’s going—and who doesn’t. We also have the youngsters undergo neuroimaging and cognitive testing, seeing if biological measures help us improve diagnosis. Are there clear differences in brain structure? In processing of information? Where are you headed? Here’s what he says: We know you were set on becoming a neurosurgeon until a child psych rotation in med school turned that around, but what sparked your pediatric bipolar interest? Early on, a colleague in Cleveland with adult patients with bipolar disorder didn’t know where to turn to help their troubled children—some as young as 6 or 7. The patients would say: I’m terrified for my son. How can I keep him from suffering as I have? So the youngsters came to my office. With their cluster of symptoms—often compounded by ADHD or oppositional defiance disorder—they didn’t look quite like kids I’d seen in training. You quickly saw a pressing need both for the LAMS study and a different approach, yes? Correct. Most studies of pediatric bipolar start with the adult disease in mind. Then they look at symptoms in children to see whether they match that better than other childhood disorders. Sort of like trying on Cinderella’s glass slipper? Yes. But that can wrongly presume that the “bipolaresque” kids are the only ones who suffer from bipolar disorder. Perhaps worse, it assumes that youth who are “bipolaresque” indeed have bipolar illness and are likely to suffer from it as adults. And we now know that many do not. LAMS, however, started without presumptions, with only this cluster of SUPPORTING THE CAUSE A Double Dose of Help W hen Charles Ellzey worked some 30 years as a ship’s engineer for the Alcoa and then the Central Gulf Steamship Lines, Johns Hopkins never crossed his path. It wasn’t until the sister of his wife Helen showed signs of dementia that Ellzey found himself in East Baltimore regularly in 1983, “for diagnosis and whatever help Hopkins could give us.” Of course, no cure exists for Alzheimer’s disease (AD). “But,” says Ellzey, “the moral support alone that we got during the hard job of caring for my wife’s sister made us feel that we weren’t out in the forest by ourselves.” During one later visit, a grateful Ellzey asked how he might help the cause. It wasn’t long before he’d signed on as a healthy control in a long-term study, the Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center’s Longitudinal Evaluation. Over the next 30 years, this helpful, “resilient man” as the study’s director, Constantine Lyketsos, dubs him, has come to Johns Hopkins annually for a battery of tests—part of the research. Those at risk of AD are followed to shed light on the illness’s course and biology. And controls like Ellzey allow crucial comparisons with normal aging. “I always get a kick out of coming,” he says. But Ellzey didn’t stop there. When Helen passed away in 2007, a generous bequest soon after her death honored his beloved wife while it advanced research. And this year, with a charitable gift annuity, Ellzey—now 85—extends both the support and honor. n The long-term reports from LAMS are almost out—what happens to these children with time. That’s where the rubber meets the road. Then, immediately, we should start translating that into prevention, change the course of things. We know that for bipolarity, the earlier the onset, the worse the adult outcomes. So if LAMS tells us who’s at risk, there’s a real opportunity to intervene before the most pernicious effects take hold. Nip it in the bud, then. We hope. Nip at buds too early and you risk not getting the right bud. And if you’re a long time away, age-wise, from a condition’s most extreme expression, you’re more likely to be imprecise. These are vulnerable, vulnerable children: Misdiagnose and treat too early and you expose kids to medicines with real side effects, not to mention label them for life. Fail to catch it early enough and you add to human suffering. We struggle with this. Is there any better justification for research? Alcohol Withdrawal Screening Questions New Way for Withdrawal I s it a dream? I can’t distinguish things. I was sure I was back in a bar. I had no idea I was in a hospital. Being in a major U.S. medical center while in the midst of alcohol withdrawal, as this actual patient was, isn’t rare. A surprising 17 percent of patients on general medical wards, says one hospital survey that psychiatrist Jeffrey Hsu cites, are caught up in some stage of alcohol withdrawal. That can jump to 50 percent in emergency or intensive care settings, he says— even more in specialized, smaller inpatient units for the very ill with known substance abuse. What’s also unexpected is that many hospitals lack a standard, updated approach to the problem. Without that, diagnosis can be tricky. Patients’ earlyon withdrawal symptoms of insomnia, racing heartbeat, sweating or fever can be attributed to anxiety or infection, even overzealous coffee-drinking. And treatment is less likely patienttailored. “At a suspicion of alcoholism, it’s not unusual for patients to routinely get high-dose benzodiazepines followed by a multi-day tapering,” Hsu says. “That can lengthen hospital stays, not to mention hitting patients with higher sedation.” So a few years back, Hsu helped start a cross-hospital group to explore change. It came first from tactics to raise safety on Johns Hopkins psychia- Serum blood alcohol level is positive NO Have you consumed any beer or other alcohol containing drinks within the last seven days? YES In the past week how 1 drink =12 oz beer 8.5 oz malt liquor many alcohol containing try wards. “We 5 oz wine drinks have you had in 1.5 oz spirits If > 4 NO a single sitting? wanted to idenYES tify and manIf < 4 age patients Do you drink every day? YES early in alcohol NO withdrawal, Do not start Start patient YES Have you ever had symptoms of NO alcohol withdrawal such as tremor, patient on alcohol on alcohol before the seizures, or delirium tremens? withdrawal withdrawal complication of protocol protocol seizures set in,” he says. and monitor therapy. And last, In 2011, the group designed a flow says Hsu, there’s every sign that the chart (above) to assess patients’ risk group’s new treatment protocol— of being in withdrawal. It’s now an it’s evidence-based and guided by online part of inpatient interviews. the severity of a patient’s withThere’s more: Psychiatric nurse Gigi drawal—will become the norm. n Rosenblatt headed a move to update nursing staff, and now a new computer course teaches nurses to recognize stages For information: 410-614-3618 Hopkins This newsletter is published for the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences by Johns Hopkins Medicine Marketing and Communications. 901 South Bond Street, Suite 550 Baltimore, MD 21231 Some of the research in this newsletter has corporate ties. For full disclosure information, call the Office of Policy Coordination at 410-223-1608. To make a gift, contact Jessica Lunken, Director of Development Johns Hopkins Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Fund for Johns Hopkins Medicine 550 North Broadway, Suite 914 Baltimore, MD 21205 Non-Profit Org. U.S. Postage PAID Permit No. 5415 Baltimore, MD Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences J. Raymond DePaulo Jr., M.D. Director Marketing and Communications Dalal Haldeman, Ph.D., M.B.A. Vice President, Marketing and Communications Marjorie Centofanti, Editor/Writer David Dilworth, Designer Keith Weller, Photography ©2013 The Johns Hopkins University and The Johns Hopkins Health System Corporation If you no longer wish to receive this newsletter, please email [email protected] Check our departmental website for more news: www.hopkinsmedicine.org/Psychiatry/index.html Hopkins T H E N EW S L ET T ER Deliriously (Un)happy Tackling the problem of hospital delirium. PAGE 1 O F T H E J O H N S H O P K I N S D E PA RT M E N T O F P S Y C H I AT RY A N D B E H AV I O R A L S C I E N C E S SPRING 2013 Stress in Teens Circuit-Pretty Bipolar and Kids Mouse study suggests it’s a psychiatric hazard. Brain Stimulation for Alzheimer’s? Bringing it into sharper focus. PAGE 2 PAGE 2 PAGE 3