* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Week 2 (Norton), part a (pdf, 2.2 MB)

Survey

Document related concepts

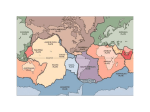

Transcript

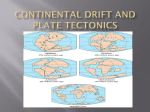

Benchley was a radio stand-up comedian in the first half of the 20th century. I guess he specialized in being caught in awkward situations that required quick thinking to extricate himself as gracefully as possible Show of hands: How many of you think that scientific experiments, or explorers’ plans, generally go as they were originally expected to go? Show of hands: How many of you think that Benchley’s quip illustrates—that outside influences, weird circumstances, internal mistakes and the like—are the rule rather than the exception? 1 For context, we go back to mid-19th century, when the theories of Charles Darwin galvanized biological thinking about organic evolution. How about Darwin? Did he plan to devise a wholly new way of interpreting the history of organic life on this planet at the beginning of his voyage in the HMS Beagle? What was the purpose of the Beagle’s second voyage in 1831-36? Was Darwin invited on the voyage to be the ship’s naturalist? 2 In the view of 19th century “catastrophists” (before Darwin et al.) the Earth was a static ruin, greatly damaged by the Flood of the Bible. Noah had been called upon to rescue one male and one female of each of the originally created species from the Garden of Eden, which pairs of organisms were to be spared. After the Flood’s punishment, pairs of organisms would be freed to reproduce exact replicas of God’s original creation. Paleontologists and anthropologists and linguists believe that there was a natural event about 7,500 kya that has descended to several modern religions as the flood, each appropriate to its own context. That event was the filling of the Black Sea. After the Black Sea was formed, the agrarian societies surrounding the former lake were dispersed. Remnants of their common language, Proto-Indo-European are to be found throughout Europe, the Middle East, India, and western Asia. 3 The 19th century saw the replacement of catastrophism by gradualism. Darwin’s daring notion that species were not immutable, but evolved through natural selection required time—lots of time. Hence gradual-ism, not catastrophism. In Europe, particularly, many geological symptoms of damage or catastrophe previously blamed on the Biblical Flood were now re-interpreted as the results of glacial action, from a period in which there was more alpine and continental lowland ice than there is today. In fact, Darwin, as cabin-mate to Captain Fitzroy, considered himself not as a biologist, but as a___________, because biology had not really split off as its own specialization from the rest of the field of “natural philosophy.” By the Guilded Age (1865-1900+) Gradualism or Uniformitarianism had become so firmly entrenched in the thinking of natural sciences that it governed the admissability of explanations, hypotheses and theories that were proposed. Here, for example, a high school geology textbook explains earthquake-prone regions of Earth in terms of the analogy of a cooling, shrinking celestial body, As our celestial body continues—gradually—to cool, the surface or skin wrinkles like that of a drying (hence shrinking) apple. Mountains are created as upthrust wrinkles, and earthquakes occur more frequently where these upthrust wrinkles are concentrated. What else do we notice about the geographic distribution of these dark stripes denoting “earthquake regions?” 4 Here, a modern view of such “wrinkles” in the skin of a cooling planet (Allegheny/Appalachian mountains, of W. PA in color-enhanced Satellite image). 5 1. 2. After the fact of organic evolution had been acknowledged, and the theories of natural selection adopted by 19th-20th century scientists, their world view settled on newer models for what accounted for the shape and features of Earth. Newer models needed to be at peace with the newer philosophic basis for thinking about the changes of the world over time, which we call “uniformitarianism” or “gradualism” that replaced the construct of “catastrophism.” First was the cooling-contraction model, in which an initially hot, molten planet was unidirectionally cooling to this day. The analog is a drying apple, in which wrinkles are raised by the slowly shrinking core and flesh underneath. These wrinkles represent mountain ranges. (A problem with the contraction model was that if a geologist could stretch out all the folds and wrinkles known to science at the surface, Earth would have had to be unimaginably large at its initiation.) Second, geologists—notably Alfred Wegener—returned to the tantalizing geometry of existing continents, to argue that they must have wandered over the surface of the planetary sphere: continental mobility or continental drift. 6 The principle of isostasy in geology dates from 1889 (Dutton). If you put a load onto the plastic upper layer of Earth’s mantle, gravitational forces will deform the asthenosphere as this load floats on top of it. Examples of such deformation in a uniformitarian régime of thinking include eroded materials that spread downhill, ice masses that build up on continents and depress underlying landforms, and continental edges in areas of compression (due to global cooling and shrinking) where upthrust rock depresses underlying layers. 7 In 1912-15, at the outset of the Great War, a young German meteorologist, Alfred Lothar Wegener, came up with the idea that continents, like biological species for Darwin, were not fixed in their spatial relationships to one another. Rather, as Wegener termed it, relatively less dense continental crust must somehow “drift” across the surface of the planet floating on denser material deeper in the earth. His argument rested in no small part on the good fit between certain continental boundaries, such as those of South America and Africa. He also knew enough about paleontology to compare fossils across these supposedly drifted-apart continents, finding that ancient land vertebrates, for example, looked more similar if not identical, unlike modern fauna or flora. Subsequent to Wegener, other geologists refined models of ancient fits between continents. 8 To get the most out of looking at 20th century refinements to new paradigms in science, it is useful to visualize one or more time scales: Here’s a basic time scale, from AD 1875 (1875 CE) to 2025 covers the 150 years from just after the Alaska purchase of 1867 to a decade and a half into the future. This is an unabashedly a linear time scale (representing time’s arrow, not time’s cycle). Just for reference, here’s a vertical arrow that covers 100 of the 150 years represented. 9 Credit the seminal contributions of James Hutton, 18th century Scottish geologist, to Uniformitarianism or Gradualism for this linearity in historical thinking. This linearity emphatically replaced the catastrophism in some biblical accounts of events, such as the Mosaic Flood stories. Simply put, in our 150-year timeline, the main story is what happened to Wegener’s theory of Continental Drift between 1915, and 1967, when the derivative theory of Global (Plate) Tectonics is considered to have been fully accepted? The key years turn out to be between 1925 and 1967. And there is no one authoritative account of this scientific “paradigm shift,” but at least three sets very different analyses. First is the account by a participating scientist, H.W. (Bill Menard) who published in 1986 (but posthumously) work that he had basically analyzed and followed closely through 1982. Next, a leisdurely series of analyses that spanned the years from 1986 through 2012, by John Nance, Brian Atwater, George Plafker, and even Dave Norton. In the middle of that great span (1982-2012) two books (Oreskes 1998 and Oreskes et al. 2006). 10 “(C) Continental platforms developed and sedimentary rocks were deposited in shallow seas along their margins. Riftlike troughs cut the continents, suggesting that some type of plate tectonics began in this stage. Life expanded, producing oxygen in the atmosphere. Carbon dioxide was removed to form carbonate sedimentary rocks, reducing the pressure of the atmosphere dramatically. (D) Plate tectonics persisted as lithospheric slabs participated in the convection of the mantle. The continents grew slowly, but rifting, mountain building, hot-spot activity, and climate change produced oscillations in the level of the sea, yielding cycles of marine deposition on the continents. Pangaea, a large super continent, developed by collision of smaller blocks of continental crust. Life rapidly diversified in the seas and eventually on land as well. (E) The breakup of Pangaea about 300 million years ago followed as a result of rifting and the growth of a new ocean basin. The continents took on their present outlines.” Source: http://explanet.info/Chapter08.htm 11 There has been a tortuous path of scientific conjecture, or history of theoretical explanations for the supposed fit of continents that Wegener (like others, going back at least to the 17th century had noticed from reading navigational charts). For a while in the 20th century, one school of theorists started with the proposition that Earth, instead of cooling and shrinking, is actually expanding from a stage when the entire planet was covered by continental crust. Gradually, the planet has doubled in size, the continents somehow making room for the oceans. I cannot tell you how this school of thought explained the expansion. Perhaps a whole series of punishments for human sins in the form of many, many “40 days and nights of rain…” 12 These analyses are complementary as much as they are competitive. Each of the camps has a different emphasis, and they probably took various gestation times for good reasons, even if I don’t fully grasp those reasons. Menard (published 1986, or 1967 + 19 yr) had retired from a distinguished, high-profile, lavishly funded, scientific career among top-notch scientists from leading research institutions in Europe, North America, and Asia, whose intellectual contributions were mainly concentrated in the decades from the mid-1930s to the mid 1960s, and which perhaps necessarily included the WW II years (1939-1945). Most of these scientists spent most of their field time at sea, teasing clues from the sea floors of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The series of retrospective analyses by John Nance, Brian Atwater, and George Plafker (published 1988-2012 or 1967 + 21 to 45 yr). Their emphases were all directed toward the field verifications of Plate Tectonic Theory by seismologists and related disciplines involved in analyzing catastrophic events related to earthquakes, tsunamis, turbidity plumes, and volcanic eruptions. Naomi Oreskes and co-authors published two major works in 1999 and 2003 (1967 +32 and +36 yr). Their focus was to wonder retrospectively what took western scientists so long to drop its collective, chiefly academic, resistance to continental drift and to global tectonic theory. 13