* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download synagogue services 2012 version

Origins of Rabbinic Judaism wikipedia , lookup

History of the Jews in Gdańsk wikipedia , lookup

Jewish views on sin wikipedia , lookup

Baladi-rite prayer wikipedia , lookup

Jewish religious movements wikipedia , lookup

Jewish views on evolution wikipedia , lookup

Pardes (Jewish exegesis) wikipedia , lookup

Index of Jewish history-related articles wikipedia , lookup

Romaniote Jews wikipedia , lookup

Independent minyan wikipedia , lookup

Jewish views on religious pluralism wikipedia , lookup

Bereavement in Judaism wikipedia , lookup

Jewish holidays wikipedia , lookup

Hamburg Temple disputes wikipedia , lookup

The Reform Jewish cantorate during the 19th century wikipedia , lookup

Judaism

Synagogue Services

© Sharon Brien

© Sharon Brien

Basic Beliefs of Judaism

One G-d: creator and ruler of the universe

A moral law prescribed by G-d

The Covenant

© Sharon Brien

Syllabus

Students learn about:

Students learn to:

ONE significant

describe ONE significant

practice within

practice within Judaism:

Judaism:

Synagogue services

Synagogue services demonstrate how this

practice expresses the

beliefs of Judaism

analyse the significance of

this practice for both the

individual and the Jewish

community

© Sharon Brien

© Sharon Brien

Observance - Devotion

Devotion in Judaism is understood as

observances that are obligatory actions. These

include daily prayer and weekly synagogue

service as well as marking significant events

such as birth, puberty, marriage and death.

© Sharon Brien

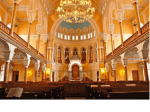

Synagogue services

The word synagogue means “leading together”.

Synagogue is commonly spoken of as a “Shul" by

Orthodox Jews, “Synagogue" by Conservative, and

"Temple" by Reform. "Synagogue" is a good all-around

word to cover the preceding three possibilities.

The activities of the synagogue are many and varied.

In most places the synagogue faces towards Jerusalem

reflecting the importance of the city for Jews.

The emphasis in Jewish worship in on avadah sh’belev –

worship of the heart.

© Sharon Brien

Synagogue organisation

Synagogues are generally run by a board of directors composed of lay people.

They manage and maintain the synagogue and its activities, and hire a rabbi for

the community. It is worth noting that a synagogue can exist without a rabbi:

religious services can be, and often are, conducted by lay people in whole or in

part. It is not unusual for a synagogue to be without a rabbi, at least temporarily.

However, the rabbi is a valuable member of the community, providing

leadership, guidance and education.

Synagogues do not pass around collection plates during services. This is largely

because Jewish law prohibits carrying money on holidays and Shabbat.

Tzedakah (donation) is routinely collected at weekday morning services, but this

money is usually given to charity, not to the synagogue itself. Instead,

synagogues are financed through membership dues paid annually, through

voluntary donations, through the purchase of reserved seats for services on

Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur (the holidays when the synagogue is most

crowded), and through the purchase of various types of memorial plaques. It is

important to note, however, that you do not have to be a member of a

synagogue in order to worship there.

Synagogues are, for the most part, independent community organisations.

There are central organisations for the various movements of Judaism, and

synagogues are often affiliated with these organisations, but these organisations

have no real power over individual synagogues.

© Sharon Brien

© Sharon Brien

© Sharon Brien

© Sharon Brien

© Sharon Brien

© Sharon Brien

Aspect of devotion

Features: synagogue service

Officiating celebrant

Rabbi or representative of the minyan leads

the ritual

Role of the community

Cantors respond to the prayers lead by the

rabbi

Orthodox and conservative service is

conducted in Hebrew

Rabbi highlights key features of the reading

instructing participants

Use of Sacred text

Torah

© Sharon Brien

Aspect of devotion

Features: synagogue service

Features of the synagogue Aron ha-kodesh – Ark where the Torah

Scrolls are kept

Torah Scrolls – can only be read if a minyan

is present

Ner Tamid – Eternal light which burns

permanently in front of the Ark

Bimah – the raised platform from which the

Torah is read directly in front of the Ark and

traditionally in the centre of the building.

A kippah or yamulke is the cap worn by

Jewish men.

A talit or prayer shawl is worn by Jewish

men

Tefillah or phylacteries contain passages

from Exodus 13 and Deuteronomy 6 and 11

which require Jews to bind these

commandments upon their hands and

between their eyes,

Siddur – the daily prayer book

© Sharon Brien

© Sharon Brien

The Ark

The Aron HaKodesh (Holy Ark) is what makes the worship

space a synagogue. Any room can be used for prayer, and

Jew frequently pray in the study hall or someone's home. A

room with a permanent Ark is a synagogue. The Ark contains

at least one Torah scroll, a handwritten scroll containing the

Five Books of Moses (called in Hebrew the Chumash; also

known as the Pentateuch in English). Many congregations

own several scrolls. It is a great honour to be able to give the

synagogue a Torah scroll as a gift. The presence of the Ark

renders the room sacred space. Often, other objects will be

stored in the ark, as well, including a Megillah (the Scroll of

Esther read on Purim), perhaps a Havdalah set (including

the candle and spice box used for the ceremony concluding

Shabbat) and occasionally a shofar (the ram's horn blown on

Rosh Hashanah). Storing these items in the Ark is a matter

of convenience. The essential thing is the Sefer Torah (scroll

of Torah).

© Sharon Brien

The Ark of a modern synagogue is reminiscent of the ark

in which the Israelites kept the Torah which, according to

tradition, G-d gave Israel through Moses on Mount Sinai.

The Ark of the Covenant was a wooden box overlaid with

gold, which the Israelites carried with them throughout

their 40 years of wandering in the wilderness, and then

brought to the Land of Israel where it was kept at the

religious center in Shiloh. King David brought it to

Jerusalem, amidst a procession including music and

dancing, when he made the Holy City his capital. After

King Solomon built the Temple in Jerusalem, the ark was

installed in the Holy of Holies, the inner sanctuary, of the

Temple.

Whenever the ark is opened, the congregation is

expected to stand. The congregation prays facing the

ark; the ark faces Jerusalem. Thus, all Jews face

Jerusalem when they pray. For Jews, Jerusalem is the

spiritual centre of the universe.

Parochet

The Ark is covered by a curtain, called a

parochet, just as the Holy of Holies in the

Temple in Jerusalem, was separated from

the rest of the sanctuary by a curtain

called a parochet. The parochet remains

closed throughout the service except when

the Torah is removed and returned to the

Ark.

© Sharon Brien

© Sharon Brien

Ner Tamid

An Eternal Light (Ner Tamid) hangs above the ark in

every synagogue. It is often associated with the

menorah, the seven-branched lamp stand which stood in

front of the Temple in Jerusalem. The Ner Tamid as a

symbol of G-d's eternal and imminent presence in the

communities and in the lives of all Jews. It is also

symbolic of their eternal covenant with G-d; for Jews.

Where once the Ner Tamid was an oil lamp, as was the

menorah which stood outside the Temple in Jerusalem,

today most are fuelled by either gas or electric light

bulbs. They are never extinguished or turned off.

© Sharon Brien

© Sharon Brien

© Sharon Brien

The Torah Scroll

The Torah contains the Five Books of Moses, whose English and Hebrew

names are:

Genesis Beraishit

Exodus Shemot

Leviticus Vayikra

Numbers B'midbar

Deuteronomy Devarim

The Torah is divided into parshiot (Torah portions) which are generally three

to five chapters in length. The parshiot are read, in order, each Shabbat

throughout the year, in a yearly cycle which begins and ends on Simchat

Torah (a holiday which follows Sukkot).

On holy days, festivals and other special occasions, special passages

outside the cycle of reading are read.

Hebrew consists of consonants and vowels. However, unlike English, most

printed Hebrew contains only consonants. In fact, the vowel system in

Hebrew, which appears to many as a series of dots and dashes under and

around the consonants, was invented sometime around the fifth century,

when Jews no longer spoke Hebrew has their primary language, and

required the help of vowels to pronounce holy texts correctly. Printed

editions of the Torah contain vowels, as well as cantillation symbols (called

trop) which signify the proper way to chant the text.

© Sharon Brien

Torah ornaments

The Torah is dressed and

decorated because it is

holy and is considered

the core of G-d's

communication with

Israel. The manner in

which it is dressed and

decorated, however, is

symbolic of the garb worn

by the High Priest of old

when he served G-d in

the sanctuary of the

Temple in Jerusalem.

© Sharon Brien

© Sharon Brien

Kippah (Yarmulke)

It is customary for Jews to wear a head covering when

praying. Many Jews wear a head covering whenever

they are awake, with the exceptions of bathing and

swimming. In Hebrew, the small, round head covering

worn out of respect for G-d, and as a sign of recognition

that there is something greater and above us, is called a

kippah, which literal means "dome" or "cuppola." The

Yiddish word is yarmulke. The kippah also serves as a

symbol of Jewish identity and loyalty.

The minhag (custom) of wearing a kippah has no basis

in Jewish law, either in the Bible or later rabbinic law.

A more traditional slant on the etymology of yarmulke

holds that it derives from the expression yarei

mei'Elohim ("in awe of G-d"), based upon the statement

by Huna ben Joshua (5th century Talmudic scholar) who

said, "I never walked four cubits with my head uncovered

because G-d dwells above my head“.

© Sharon Brien

Books

Two books are used during Jewish prayer; the siddur (prayer book) and the

chumash (a printed edition of the Torah).

The term "siddur" is derived from the Hebrew root "order" because the

prayers are recited in a prescribed order. The prayer book was developed

over the course of more than 2000 years, with additions and amendments

from virtually every age and generation. There are many different prayer

books in use these days, reflecting the differences among Jewish

communities, however the overall structure, and much of the wording is the

same in all of them.

A printed edition of the Torah, called a chumash, is used when the Torah is

read, so that the congregation can follow along with the reading. Most

chumashim (plural of chumash) have the Hebrew text with an English

translation printed in facing columns. Below you will often find a line-by-line

commentary explaining the editor's interpretation of the text. There are

many editions of the chumash in print, ranging from very traditional

approaches, to far more liberal and academic interpretations.

Both the siddur and the chumash are considered sifrei kodesh (holy books)

because they contain the tetragrammaton (the ineffable Name of G-d). They

should never be placed on the floor or left sitting open and unattended on

the chair. If a volume is dropped accidentally, it is customary to pick it up

and kiss it.

© Sharon Brien

© Sharon Brien

Shofar

A shofar is an instrument made from the horn of a ram or

other kosher animal. It was used in ancient Israel to

announce the New Moon (Rosh Chodesh) and call people

together. It was also blown on Rosh Hashanah, marking the

beginning of the New Year, signifying both need to wake up

to the call to repentance, and in connection with the portion

read on the second day of Rosh Hashanah, the Binding of

Isaac (Genesis, chapter 22) in which Abraham sacrifices a

ram in place of his son, Isaac.

Today, the shofar is featured most prominently in the Rosh

Hashanah morning services. It is considered a

commandment to hear the shofar blown.

It must be an instrument in its natural form and naturally

hollow, through which sound is produced by human breath,

which G-d breathes into human beings. This pure, and

natural sound, symbolizes the lives it calls Jews to lead.

What is more, the most desirable shofar is the bent horn of a

ram. The ram reminds one of Abraham's willing sacrifice of

that which was most precious to him. The curve in the horn

© Sharon

Brien

mirrors

the contrition of the one who repents.

© Sharon Brien

Menorah

The seven-branched lamp stand which stood in the Temple in

Jerusalem is symbolised in many modern sanctuaries by the

menorah. The seven branches, mirroring the seven days in a week

(the Six Days of Creation plus the Sabbath) reflect Creation itself

© Sharon Brien

Luchot

It is customary to have a representation of the Ten

Commandments over the ark, symbolising the Torah which is

inside the ark. Depictions of the luchot (tablets) on which the

Ten Commandments were inscribed give rise to many Jewish

art forms.

The Ten Commandments are found twice in the Torah:

Exodus, chapter 20 and Deuteronomy, chapter 5. There are

minor differences between the two versions, in Exodus and

Deuteronomy. For example, Exodus cites creation as the

reason for keeping Shabbat, while Deuteronomy cites the

experience as slaves in Egypt as the primary reason.

Similarly, while Exodus tells Jews to remember the Sabbath

day and keep it holy, Deuteronomy instructs them to observe

the Sabbath day and keep it holy (this, by the

way, is the source of the tradition of lighting

two candles as Shabbat begins: one each for

remember and observe).

© Sharon Brien

Tefillin

Tefillin (t’FĬL-lĭn), called phylacteries in English, are worn

by observant Jewish men and by some Jewish women as

a reminder of their Covenant with G-d. They are put on

during morning prayers only, not on the Jewish Sabbath

or most holidays because these times are signs in

themselves of the Covenant between the Jewish People

and G-d.

Tefillin consist of two leather boxes. Each box contains

strips of parchment inscribed with the four passages of

the Torah that mention the mitzvah (commandment) of

wearing tefillin. Deuteronomy 6:4-9 , Deuteronomy 11:1321, Exodus 13:1-10 and Exodus 13:11-16.

© Sharon Brien

One of the leather boxes is worn on the head between the

eyes, resting on the cerebrum, to remind Jews to subject

their thoughts to G-d's service. The other box is worn on

the left arm so that it rests against the heart, and the

suspended leather strap is wound around the left hand

and around the middle finger of that hand. This to

remind Jews to subject their deeds to G-d's service and

to subject their hearts' desires to G-d's service.

© Sharon Brien

Tallit

The Lord said to Moses as follows: Speak to the Israelite people and instruct them to

make for themselves fringes on the corners of their garments throughout the ages; let

them attach a cord of blue to the fringe at each corner. That shall be your fringe; look at

it and recall all the commandments of the Lord and observe them… Numbers 15:37-39

Tzitzit (TZĒT-sēt)

These fringes or tassels attached to the corners

of the tallit are a reminder of the G-d’s 613

commandments. Each letter in the Hebrew

alphabet has a numerical value. The numerical

values of the 5 letters that comprise the Hebrew

word tzitzit add up to 600. Add the 8 strings and 5

knots of each tassel, and the total is 613. In

addition, each tzitzit should have a thread of blue

to represent the heavens.

Tallit (tah-LĒT),

Prayer Shawl

Shawl-like garment worn by observant Jewish

men and some Jewish women over the clothes

during the weekday morning service, the Sabbath,

and other holidays. There are tzitzit attached to

the corners.

© Sharon Brien

Rabbi

"Rabbi" means "teacher" and, through preaching from the pulpit,

teaching classes, and individual counselling, teaching is the primary

duty of a rabbi. In addition, many rabbis serve as administrators of

their synagogues, represent the congregation to the community,

officiate at life-cycle events, and serve as Jewish legal decisions

(that is, they render decisions concerning Jewish legal matters that

come before them).

Cantor/

Chazzan

Traditionally, a Jewish prayer service is chanted. The leader is

called the shaliach tzibbur (the representative of the community)

who recites the prayers on behalf of the people. The chazzan

(cantor) is specially trained in the art of Jewish music and liturgy for

this role.

Educator

Often, a congregation hires a Jewish educator to run its religious

school program, and its adult education program as well.

Baal Koreh

(Torah

reader)

The Baal Koreh is the Torah reader. Anyone who is at least 13

years old and possesses the skill to chant the Torah competently

may serve in this capacity. Some congregations engage a

professional Baal Koreh, and many others draw on their own

members to serve in this capacity.

© Sharon Brien

Gabbai

When the Torah is read you may well see two people standing on

either side of the reading table who assist the reader and make

sure that the Torah Service runs smoothly. These people are the

gabbaim. It is their job to call people to the Torah for their aliyot,

check that the reader makes no mistakes while reading the Torah,

and provide correction if a mistake is made, recites the Mi

Sheberach for those who have had an aliyah, and see to covering

and uncovering the Torah scroll at the appropriate times.

Hagbahah

After the Torah has been read, the congregation will be asked to

stand and someone will lift the scroll above his/her head. This

person will then turn around so that the side of the scroll with the

writing faces the congregation, and turn as necessary to enable

everyone assembled to view the scroll, enabling them to peer into

the scroll that morning. It is traditional to show a minimum of three

columns of writing, including the portion read that morning. The

honour of lifting the Torah is called hagbah. The person honoured

with lifting the torah is referred to as the hagbahah.

Gelilah

After the congregation has had an opportunity to see the scroll, the

hagbahah sits in a chair on the bima and another person, comes

forward. The person honoured with gelilah ties the sash around the

scroll, places the mantle over the scroll, and puts on the breastplate

and crown

© Sharon Brien

Minyan

Judaism places a premium on community and is structured to

encourage people to gather together for prayer, study,

celebration, and even in grief to support those who mourn. In

order to hold a complete prayer service, a quorum of ten

adults (those who are 13 years or older) is required. The

quorum is called a minyan.

People can pray by themselves, but collective worship is also

essential at regular intervals because it brings the community

together as a community. Judaism is not a religion of the

individual. It is more than a faith. It is a family-centred and

community-based culture and civilization. It fosters

interdependence and relationships with others.

© Sharon Brien

When someone dies, the mourners are obligated to

recite a prayer called Kaddish each day for eleven

months. In order to recite the prayer, they need a minyan

(the quorum required for public prayer). The result is that

the community assembles in their home while they are in

mourning to enable the mourners to say Kaddish and

thereby are able to provide support and consolation.

Once the period of mourning is completed (7 days), then

the mourners need to come to the synagogue to join the

minyan there in order to say Kaddish. The result again is

that they cannot isolate themselves in their grief, but

must come back to the world and back to the community,

where they will be supported and nurtured as they work

through their grief.

Jews need to come together to accomplish the manyfaceted aspects of worship: prayer, study, celebration.

All these things require the presence of other people; all

are enhanced by the presence of other people. Hence

collective worship is very important -- indeed essential -for Jews.

© Sharon Brien

Question time

1.

2.

3.

© Sharon Brien

Describe the key features, roles and dress you would expect to find

in a synagogue?

How do these elements reflect the key aspects of Judaism?

Create a mind map of the information you have about the

synagogue and synagogue services so far.

Synagogue service

Features:

Structure of the ritual

Morning Service Shacharit 6.00 am

Verse of Praise

Shema – the declaration of the oneness of

G-d (Deuteronomy 6:4-9, 11:13-21, Numbers

15:37-41)

Amidah - a prayer consisting of eighteen

blessings

Kaddish is said

Hallel – Psalms 113-118 are said on the

festivals of Passover, Sukkot and Hanukkah

Torah reading

Alenu – a prayer proclaiming the greatness

of G-d

© Sharon Brien

Synagogue Service

Features:

Structure of the ritual

Afternoon Service Minchah 6.00 pm

Ashrei – reading from psalms

Amidah - a prayer consisting of eighteen

blessings

Kaddish is said

Alenu – a prayer proclaiming the greatness

of G-d

Evening Service the Ma’ariv 6.15 pm

Recited directly after the Minhah

A minyan is required

Shema

Amidah - a prayer consisting of eighteen

blessings

Alenu – a prayer proclaiming the greatness

of G-d

© Sharon Brien

There are multiple reasons for there being three daily

prayer services but the usual explanation is that each one

of the three was initiated by one of our patriarchs: Abraham

(Genesis 22:3 -- "Abraham arose early in the morning"),

Isaac (Genesis 24:63 -- "Isaac went out meditating in the

field toward evening"), and Jacob (Genesis 28:11 "He came

to that place and stopped there for the night"). In fact, the

prayer services are also substitutes for the sacrifices made

in the Temple in Jerusalem prior to its destruction in 69/70

C.E. The morning prayers (Shacharit) and afternoon

prayers (Minchah) correspond to the morning (Tamid

offering) and afternoon sacrifices (the second Tamid). The

evening service, Ma'ariv, is not associated with a sacrifice.

Rather, it derives from the obligation to say the Shema in

the evening (the prayer itself says "you shall recite these

words when you lie down at night and when you rise up in

the morning") hence the Shema is said in the evening and

morning, but not in the afternoon. There is also a tradition

that Daniel prayed thrice daily. There was a time in Jewish

history when Ma'ariv was an optional service; today, it is

often appended to the Minchah service.

© Sharon Brien

Sh’ma

“Hear, O Israel, the Lord our G-d,

the Lord is One”

(Deuteronomy 6:4)

© Sharon Brien

Shema

One of the most important of all Jewish prayers is called the Shema.

The Shema affirms belief and trust in the One G-d. It is repeated by

observant Jews twice a day. It is the prayer Jews recite as their last

words before death. Its main content is loving the one and only G-d

with all one’s heart, soul and might. The first part of the Shema

(Deuteronomy 6:4-9) is as follows:

Sh'ma Yis'ra'eil Adonai Eloheinu Adonai echad.

Hear, Israel, the Lord is our G-d, the Lord is One.

Barukh sheim k'vod malkhuto l'olam va'ed.

Blessed be the Name of His glorious kingdom for ever and ever.

You shall love the Lord your G-d with all your heart, with all your soul,

and with all your might. And these words, which I [G-d] teach you this

day, shall be upon your heart. You shall teach them diligently to your

children, speaking of them when you sit in your house, when you walk

by the way, when you lie down and when you rise up. And you shall

bind them as a sign upon your hand, and they shall be for a reminder

before your eyes. And you shall write them on the doorposts of your

house and upon your gates.

© Sharon Brien

Shema

In just this one paragraph of the Shema, it

is possible to understand why Jews

designed the tefillin (phylacteries) to place

as symbols on the head (above the eyes)

and on the arm; and why most Jews place

a mezzuzah on the doorpost of their

houses to remind them of G-d.

© Sharon Brien

Kaddish

The Kaddish is a prayer that praises G-d and expresses a

yearning for the establishment of G-d's kingdom on

earth. Originally recited by rabbis when they had finished

giving their sermons (the Rabbi’s Kaddish), in time the

prayer was modified and became associated with

mourning. The prayer itself does not actually mention

death

The word Kaddish means sanctification, and the prayer is

a sanctification of G-d's name.

The emotional reactions inspired by the Kaddish come

from the fact that it is recited at funerals and by

mourners. Jewish tradition requires that Kaddish be

recited during the first eleven months following the death

of a loved one and thereafter on each anniversary of the

death, called the Yahrtzeit (YÄR-tsīt).

The first lines of the Kaddish are:

Yit'gadal v'yit'kadash sh'mei raba, b'allmaw dee v'raw chir'utei.

May His great Name grow exalted and sanctified, in the world

that He created as He willed.

© Sharon Brien

Question time

1

. Describe some key features of a synagogue service

© Sharon Brien

Impact on the Individual

and the Community

© Sharon Brien

Proving identity for the individual and

the community

Guidance for the application of Jewish

teaching for everyday life

Connects the present moment to the

historical tradition

Makes present the Covenant and its

obligations

Confirms the duties of relationships

among the members of the community

In orthodox communities it defines

gender roles

The Minyan expresses the communal

nature of Judaism

Question time

Read the table on the previous slide, Use this and the other

information in the powerpoint as the basis to create your own table

indicating the importance of synagogue services for the individual and

the community.

2 Analyse the importance of synagogue services for the individual

and the community.

1.

© Sharon Brien

Shabbat

A significant part of the celebration of

Shabbat is the participation in Sabbath

services.

© Sharon Brien

SHABBAT

6.15 pm Friday

Minchah

6.30 pm Friday

Kabbalat Shabbat – includes Ma’ariv

9.00 am Saturday

Sacharit

11.00 am or 2.00 pm

Musaf – extra Sabbath or Festival

Prayer

100 minutes before sunset Halachic shiur – study of Rabbinic Law,

customs and traditions

60 minutes before sunset

Minchah and Seudah Shishit

Post sunset

Ma’ariv and Motze – special Sabbath

blessings

© Sharon Brien

Jewish High Holy Days

Rosh ha Shanah

Rosh HaShanah literally means ‘Head of the Year’ in

Hebrew. It is the beginning of ten days of earnest reflection

and prayers when we repent the sins we have committed in

the past year and pledge to do better in the year to

come. The spirit of this day is therefore solemn, and we

spend much of the day in prayer.

Rosh HaShanah is observed on the 1st and 2nd days of

Tishrei, which is the seventh month of the Jewish year.

Tradition holds that one day is not enough for all the

searching of the heart that is called for.

Rosh HaShanah is also considered to be the birthday of the

world, the birthday of Adam (the first man), the day on which

Sarah first learned that she would have Isaac, and the day

Isaac was born. It is also the day on which Hannah learned

that she would have a child.

© Sharon Brien

Rosh ha Shanah

The sacred atmosphere of the High Holydays builds up throughout the preceding

month. Well before Rosh HaShanah and Yom Kippur, one is already in the mood

for their solemnity and introspection. Greetings during this period include k’tivah

vachatimah tovah – “Be written and sealed (in G-d’s Book) for good”. Care is

taken to perform good deeds and not to sin. In some communities the Solemn

Days were prepared for by a ta’anit dibbur, a fast from speech; since the most

common sins are committed with the tongue, one refrained as much as possible

from talk of all kinds.

The shofar is blown every weekday morning and in some places every evening

also, as a reminder that when Moses ascended Mount Sinai to ask Divine

forgiveness for the sin of the golden calf, the shofar was sounded in the Israelite

camp to warn them not to sin (Shulchan Aruch, Orach Chayyim 581).

S’lichot, penitential prayers, are said on weekdays during the last part of the

month to attune us to the thoughts, feelings and melodies of the coming days.

Everybody, not just the chazzan, should spend time looking at the Holyday

prayers, though when a certain chazzan told a sage he was going through the

prayers he was asked, “But are the prayers going through you?” The name of the

month of Ellul is said to be the initial letters of Ani L’dodi V’dodi Li, “I am my

Beloved’s and my Beloved is mine” (Song of Songs 6:3), which suggests that our

reconciliation with G-d should begin long before Rosh HaShanah.

The customary blessing of the new month (Bir’kat HaChodesh) is omitted on the

Shabbat before Tishri, because it is unthinkable that anyone is unaware of the

approach of Rosh HaShanah (some add that it is also to confuse Satan, the

symbolic accuser, and prevent him from interfering with our re-union with G-d).

© Sharon Brien

Jewish High Holy Days

Yom Kippur

Yom Kippur is probably the most important holiday of the Jewish year.

Many Jews who do not observe any other Jewish custom will refrain from

work, fast and/or attend synagogue services on this day. Yom Kippur

occurs on the 10th day of Tishri. The holiday is instituted at Leviticus

23:26

The name “Yom Kippur” means “Day of Atonement,” and that pretty much

explains what the holiday is. It is a day set aside to “afflict the soul,” to

atone for the sins of the past year.

Kippur atones only for sins between man and G-d, not for sins against

another person. To atone for sins against another person, you must first

seek reconciliation with that person, righting the wrongs you committed

against them if possible. That must all be done before Yom Kippur.

Yom Kippur is a complete Sabbath; no work can be performed on that

day. It is well-known that you are supposed to refrain from eating and

drinking (even water) on Yom Kippur. It is a complete, 25-hour fast

beginning before sunset on the evening before Yom Kippur and ending

after nightfall on the day of Yom Kippur. The Talmud also specifies

additional restrictions that are less well-known: washing and bathing,

anointing one's body (with cosmetics, deodorants, etc.), wearing leather

shoes

© Sharon Brien

As always, any of these restrictions can be lifted where a threat to

life or health is involved. In fact, children under the age of nine and

women in childbirth (from the time labour begins until three days

after birth) are not permitted to fast, even if they want to. Older

children and women from the third to the seventh day after childbirth

are permitted to fast, but are permitted to break the fast if they feel

the need to do so. People with other illnesses should consult a

physician and a rabbi for advice.

Most of the holiday is spent in the synagogue, in prayer. In Orthodox

synagogues, services begin early in the morning (8 or 9 AM) and

continue until about 3 PM. People then usually go home for an

afternoon nap and return around 5 or 6 PM for the afternoon and

evening services, which continue until nightfall. The services end at

nightfall, with the blowing of the tekiah gedolah, a long blast on the

shofar.

It is customary to wear white on the holiday, which symbolizes purity

and calls to mind the promise that our sins shall be made as white

as snow (Is. 1:18). Some people wear a kittel, the white robe in

which the dead are buried.

YOM KIPPUR

Kapparot In some communities, sins are symbolically transferred by means of a

ceremony involving waving a chicken or a sum of money over one’s head whilst

reciting a Hebrew prayer, after which the proceeds are given to charity.

Opponents of the ceremony, which derives from the 9th century, criticise it on

aesthetic, ethical and spiritual grounds, preferring the more conventional

expressions of penitence, prayer and charity.

Those who oppose it recognise that it may contain a hint of the scapegoat ritual

in the Temple but argue that the best way to rid oneself of sins is genuine

repentance. Giving money fulfils the tradition of charity and symbolises the

determination that any sins we may have committed will now be replaced by

good deeds for the benefit of other people.

Minchah

Early in the afternoon, the Minchah service is recited including the viddui

(Confession of Sins – see below), leaving time in the rest of the afternoon to

prepare for the fast and to get to the synagogue without rushing.

S’udah Mafseket

The pre-fast meal is full enough for sustenance but light enough to digest easily.

It is helpful to take as much fluid as possible before the fast to help prevent

dehydration during the day.

B’rachot

The children are blessed by their parents and the yom-tov candles are lit, as well

as a Yahrzeit memorial candle.

© Sharon Brien

Footwear & clothing

As leather shoes are not worn on Yom Kippur, non-leather footwear

is put on before the fast. white is the dominant colour in the

synagogue on the High Holydays. On Yom Kippur, not only the

officiants but often many members of the congregation wear white

garments. Males are commonly clad in the kittel, which, though

reminiscent of shrouds, symbolises purity and spiritual cleanliness.

Fasting

The day is marked by a complete fast from sunset on Erev Yom

Kippur until nightfall the following day. Rabbi Levi Yitzchak of

Berditchev said that there was a case for abolishing all the fasts

except Tishah B’Av and Yom Kippur: “On Tishah B’Av” he said,

“Who can eat? And on Yom Kippur, who needs to eat?” Apart from

abstaining from food and drink, and not wearing leather shoes, other

“afflictions” (Lev. 23:27) on Yom Kippur include abstaining from

bathing, anointing oneself and marital relations (Mishnah Yoma, ch.

8).

A secondary meaning of v’initem et nafshotechem, “you shall afflict

your souls”, may be derived from the use of the same verb in Deut.

26:5, v’anita, “you shall declare” or even “you shall sing”. Hence

Yom Kippur with all its physical deprivations is spiritually releasing

and a time to let our souls sing at our at-one-ment with G-d.

© Sharon Brien

House of

Prayer

Beit HaTefillah

THE

SYNAGOGUE

House of

Study/Learning

Beit HaMidrash

© Sharon Brien

House of

Assembly/Gathering

Beit HaKnesset

House of Gathering

Beit HaKnesset is the

Hebrew.

It is a place for the

Jewish community to

come together for all

types of meetings,

celebrations and

other community

activities.

© Sharon Brien

The Synagogue also serves as a social and cultural centre

with a fellowship hall or auditorium and kitchen and

sometimes also a more formal ballroom and catering

service for such events as Bar Mitzvah and marriage

celebrations.

The synagogue often functions as a sort of town hall

where matters of importance to the community can be

discussed.

Brotherhood and Sisterhood organisations often sponsor

cultural programs, charitable projects, and other special

events

Havorot: small, intimate fellowship groups gather based

on mutual interest (study groups, leisure activities, family

oriented groups, etc.)

In addition, the synagogue functions as a social welfare

agency, collecting and dispensing money and other items

for the aid of the poor and needy within the community.

Each synagogue is an independent democratic

community. The members choose and pay their own

Rabbi and other staff members and make their own

administrative decisions

© Sharon Brien

Meeting Rooms

The proper Hebrew term for a synagogue is a Beit

Knesset which means "House of Meeting." It is an apt

description of a synagogue, which is far more than a

House of Prayer, or a House of Study. While study and

prayer are important and crucial components of the life

of the community, there are many reasons for Jews to

gather, and the synagogue is the central gathering place

for the community. When there is an issue of importance

to discuss, a social action program to plan or launch, or

organisational meetings to be held, the synagogue is the

natural place for these to take place. When there is a

simchah (happy event) to celebrate, or reason to mourn,

people will often gather in the synagogue. The

synagogue is the hub of Jewish life.

© Sharon Brien

© Sharon Brien

© Sharon Brien

House of Learning

Beit HaMidrash is the Hebrew.

It is where Jews come to learn the Jewish language of

Hebrew and to learn about Judaism.

In most synagogues, children and adults can take

classes in Hebrew, study important Jewish religious

books and learn all about Judaism.

© Sharon Brien

Learning

Synagogues also contains classrooms and a library

for educational programs: religious ("Sunday")

school and Hebrew classes for children from

preschool through high school age, usually also

adult education classes and/or seminars; Orthodox

have Hebrew day (parochial) schools (Yeshivas)

Contrary to popular belief, Jewish education does

not end at the age of bar mitzvah. For the observant

Jew, the study of sacred texts is a life-long task.

Thus, a synagogue normally has a well-stocked

library of sacred Jewish texts for members of the

community to study. It is also the place where

children receive their basic religious education.

© Sharon Brien

A school for children is an essential feature of any synagogue

community, for the Torah makes clear that love and loyalty to G-d

involves passing the tradition along to the next generations: "You shall

love the Lord your G-d with all your heart, all your soul, and all your

being. And these words which I command you this day shall be upon

your heart. You shall teach them to your children and speak of them

when you are at home and away from home, [from the time] you arise in

the morning [until] you lay down at night..." [Deuteronomy, chapter 6]

Jews have always approached the task of educating children in the

traditions of Torah with the utmost seriousness and have always highly

prized education of all kinds. The ability to think is a gift from G-d, and

using that gift is a sacred responsibility. Children are educated from the

time they are very young to read Hebrew, understand Torah, and absorb

the many other aspects of Jewish tradition. There is a long-held tradition

that when young children begin their formal religious education, their

teacher puts honey on their schoolbook, which they lick off. This practice

conveys to young children the sweetness of learning, which the book

offers them. Most synagogues sponsor after-school and Sunday classes

for children. In some communities children may attend all-day programs

which incorporate both Jewish studies and secular studies. In recent

years, many innovative school programs have begun to include parents

in the educational process and have developed family-oriented education

programs because a great many parents feel the need to learn along with

their children. Torah study is for every Jew, from birth and throughout life.

Among the milestones of Jewish study are reaching bar/bat mitzvah

(when the youngster is considered an adult in the eyes of the community)

© Sharon Brien

For Jews, study of Torah is a form of worship, as

important as prayer. Pirke Avot, a tractate of the

Babylonian Talmud, teaches, "The world depends upon

three things: Upon Torah study, upon worship, and upon

acts of loving kindness." For Jews, these are the three

modes of serving G-d: study, prayer, deeds of kindness.

Study is considered especially important, even more

important than performing mitzvot (commandments)

because study leads to the performance of mitzvot.

According to tradition, the proper way to study is with a

partner because the relationship formed enhances the

learning for both people. When two study together, they

are more likely to increase their learning, because

together they generate more ideas and discussion,

questioning and challenging one another, and extending

the range of their inquiry through their interaction. What

is more, two who study together are more likely to study,

because being dependent upon one another, they

cannot decide that something "more urgent" has come

up and put off study.

© Sharon Brien

© Sharon Brien

House of Prayer

In Hebrew Beit

HaTefillah.

It is where Jews come

to worship G-d.

Jews also worship at

home but worshipping

with others is an

important part of

Judaism.

© Sharon Brien

© Sharon Brien

When Israel gathers to pray, they do not pray

together as one, but each and every

synagogue prays by itself: first this

synagogue and then the next one. And when

all the congregations have finished all their

prayers, the angel responsible for prayer

takes all the prayers from all the synagogues

and makes of them crowns to place upon the

head of the Holy One, Blessed be G-d.

[Midrash Shemot Rabbah, Parashat Beshallach]

© Sharon Brien

Question time

1

. Evaluate the significance of the synagogue for the Jewish

community.

© Sharon Brien

© Sharon Brien

Orthodox

Conservative

Progressive

Men and women

are seated

separately

Men and women

sit together

Men and women

sit together

Use Hebrew in

services

Usually use

Use vernacular in

Hebrew in services services with

increasing use of

Hebrew

Leader of the

service has his

back to the

congregation

Leader faces the

congregation

Minyan is strictly

ten men

© Sharon Brien

Leader faces the

congregation

Flexibility about

what constitutes

the minyan

Question time

1

. Outline the key similarities and differences between Orthodox,

conservative and progressive synagogues.

© Sharon Brien

Question time

1. Watch the following clips and summmarise the information

http://video.answers.com/geography-of-the-synagogue-1137227

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Z_gyc7yG_c&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OmrynNxirh4&feature=related

http://video.answers.com/terms-synagogue-and-ritual-objects-961770

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9P9xdIaR0kk&feature=related

2 Watch the following clip of the largest synagogue in the world which is in Jerusalem.

Because the commentary is in Hebrew you will not be able to understand the voice over.

Nevertheless make some observations about the insights this clip offers.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZT9RG_pSorw&feature=related

3 Work through the powerpoint carefully listing the words highlighted in a different colour.

Write brief definitions for these terms.

4 You will need to think back to the Preliminary course. (check the first slide) How do

synagogue services emphasise the principle teachings of Judaism?

© Sharon Brien

Reference List

Bulmer, P. & Doret, K 2008 Excel HSC Studies of Relgion I & II Pascal Press Glebe

Clark, H. 2010 Dot Point HSC Studies of Relgion Science Press Marrickville

Clark, H. 2009 Spotlight Studies of Religion HSC Science Press Marrickville

Devine K 2008 Studies of Religion 2 Unit Preliminary and HSC Devine Educational

Consultancy Service

Hartney C & Noble J 2007 Cambridge Studies of Religion Stage 6 Cambridge

University Press Melbourne 2008

Hayward, P. Buchanan, J.Gerner, K. & Cheek J 2007 Macquarie Revision Guides

HSC Studeis of Religion Macmillan Edition South Yarra

Hollis, S, 2006 Teacher’s Friend: Studies of Religion HSC Stage 6 Syllabus NSW

King, R, Smith, H. Pattel-Gray A, Mooney, J Hohns A, Hollis, S, Carnegie E.,Johns D

McQueen K 2009 Oxford Studies of Religion Preliminary and HSC Course Oxford

University Press Melbourne

.Morrissey, Mudge, Taylor, Bailey & Rule 2010 Living Religion Fourth Edition Pearson

Education Australia, Melbourne

OLMC Notes 2006

Smith, H: Mooney, J.:King, R. & Carnegie, E. 2007 The Leading Edge HSC Studies

of Religion Study Guide 1 Unit and 2 Unit Harcourt Education Melbourne

© Sharon Brien