* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Infective Endocarditis - Oregon Institute of Technology

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

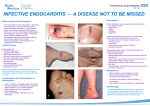

Infective Endocarditis By: Katie Walton Infective Endocarditis • An infection in the endothelium (the innermost lining of the heart). • 2 to 4 people out of every 100,000 are infected every year with endocarditis. • It most frequently occurs in males over 50. • Of people who are infected with endocarditis, 65 percent have been diagnosed with a predisposing heart condition. Signs and Symptoms • It doesn’t present to be life threatening, but it is very important to recognize. • Develops rather slowly in many cases, however, it may develop quickly. • Speed of infection depends on the bacteria which is causing the infection. • Some early symptoms include: rash, headache, fever, weight loss, backaches, anemia, fatigue, night sweats, confusion, and joint pains. Signs and Symptoms (Continued) • As the infection advances, little dark lines, referred to as splinter hemorrhages, appear beneath the fingernails. Signs and Symptoms (Continued) • A more prominent symptom of this disease is a heart murmur caused by irregular flow of blood through flawed or damaged valves. • The change of blood flow across the valves is due to bundles of bacteria, fibrin and cellular debris which accumulate on the valves of the heart. • The two most common valves affected during heart murmurs are the mitral valve and the aortic valve. • The doctor also may detect an enlarged spleen and mild anemia included in his findings. Etiology • The cause is usually transient bacteremia, which is the existence of bacteria in the blood. • This frequently occurs during dental, surgical, upper respiratory, urologic, and lower gastrointestinal procedures. • The infection could cause build up on the heart valves, lining of the heart, or the lining of the blood vessels. • If the build up were to be dislodged it could send clots to the brain, lungs, kidneys, or spleen. Etiology (Continued) • There are several different kinds of bacteria which could be the root cause of endocarditis. • An organism frequently found in the mouth called Streptococcus viridans is accountable for about half of all bacterial endocarditis. • Further widespread organisms include Staphylococcus and Group D Streptococcus. • Studies have suggested that 60% to 80% of patients with bacterial endocarditis will be diagnosed with some form of predisposing cardiovascular defect. Etiology (Continued) • Rheumatic heart disease is found in about 30% of bacterial endocarditis cases. • Congenital heart disease is found in approximately 10% to 20% and mitral valve prolapse in about 10% to 33% of cases. • Reports verified an increased threat of bacterial endocarditis among drug abusers. • There is a 30% chance of developing endocarditis within 2 years of becoming an intravenous drug addict. This is due to the use of non-sterile needles which permit bacteria to flow directly into the bloodstream. Pathogenesis • Endocarditis takes place when bacteria enter into the bloodstream. • Bacteria are usually introduced into the bloodstream through an infection found in another branch of the body. • This bacterium then contaminates damaged endocardium or endothelial tissue, situated close to high-flow shunts, between the arterial and venous channels. • Additional microorganisms including fungi and viral infections, could infect these areas, but it is rare. Pathogenesis (Continued) • Bacteria can also be forced into the bloodstream in the event of a surgical procedure, dental treatment, or even while brushing your teeth. • Many of the bacteria that invade the bloodstream are destroyed by the immune system. • The ones that survive will bunch together on a heart valve or a different segment of the endocardium. • Infection will occur shortly after and the immune system is unable to clear it out. Pathogenesis (Continued) • Shortly after, little bunches of matter called vegetations will build up on the infected valves. • This vegetation includes bacteria, small blood clots, and additional waste from the infection, which might prevent the affected valves from opening and closing properly. • It is also possible for the infection to damage these affected valves and move into additional areas of the endocardium or heart tissue. Prognosis • The expected outcome depends on whether it is detected before the heart function begins to deteriorate. • It can usually be cured if diagnosed and treated by an early stage. • In some cases, if detected soon enough it can be treated with antibiotics. • In other cases, however, the infection may be too advanced and the heart could sustain serious damage. The patient needs to get treatment as soon as possible. Prognosis (Continued) • Patients may also die from serious complications such as damaged heart valves which lead to heart failure. • A large piece of vegetation could also break off and obstruct the current in a main artery causing death. • If an artery in the brain were to be obstructed it could lead to a stroke or sudden failure of vision in one eye. • Patients who develop vegetation larger than 10 mm, have a greater chance of morbidity and mortality than patients with minor vegetation. Prognosis (Continued) • Surveys have established an outcome of patient recovery following successful therapy. • Native valve vegetation which is resolved in patients is 25% to 30%. • Decrease in vegetation accumulation is 15% to 20%. • Vegetation with unchanged accumulation is 35% to 40%. • Increase in vegetation accumulation in patients is 10% to 15%. • Continual vegetation usually become fibrosed and seldom calcified. Prognosis (Continued) • Patients who develop major valve dysfunction have a 15% to 30% risk of dying in surgery and 50% to 70% chance of overall survival if they live 1 to 2 years following surgery. Diagnostic Tests & Treatment • Endocarditis can be identified by recognizing symptoms as mentioned earlier, particularly if the patient has a predisposing condition. • It is especially important to hospitalize patients who are suspected of having endocarditis, and provide treatment as needed. • Diagnostic tests may consist of X-rays of the heart and lungs, an echocardiogram, laboratory blood counts and blood cultures, which are tested for bacteria, or an ultrasound scan of the heart (electrocardiogram). Diagnostic Tests & Treatment (Continued) • Echocardiography and electrocardiograms are the most reliable tests to diagnose infective endocarditis. • Echocardiography is used to see valve structure and function, heart wall motion, and overall heart size. • Ultrasound (electrocardiograms) provide reflected sound waves to produce a representation of the heart. • This allows the physician to spot any damage in the heart valves or vegetation that has built up. Diagnostic Tests & Treatment (Continued) • Medications called antibiotics, which kill the microorganisms in your bloodstream and within the vegetations, are the first line of treatment. • Antibiotics may be given for as long as six weeks to control the infection. • If the vegetation has damaged the heart valves surgery may be needed to repair or replace the damaged valve. Conclusion • Infective endocarditis is a very serious heart disease. • It is important that people recognize and understand the risks involved. • Certain precautions can be taken in order to prevent this disease. • If you have any heart valve damage or a heart murmur it is important that you request antibiotics prior to any medical procedures that may introduce bacteria into the blood. Conclusion (Continued) • This includes dental work, childbirth, and surgery of the urinary or gastrointestinal tract. • Don’t use illicit drugs such as heroin or cocaine. • Consumption of alcohol should be in moderation and remember to always maintain good oral hygiene. • Thank you are there any questions? • References • AllRefer Health. “Infective Endocarditis.” A.D.A.M. 2003. Retrieved February 10, 2006 from http://health.allrefer.com/health/infectiveendocarditis-info.html • Beckerman, James M.D. “Infective Endocarditis.” Personal MD 2000. Retrieved February 1, 2006 from http://www.personalmd.com/news/inf_endo_041100.shtml • Endocarditis. “Bacterial or Infective Endocarditis.” General Illness Information 2004. Retrieved on February 10, 2006 from http://www.rxmed.com/b.main/b1.illness/b1.1.illnesses/ENDOCARDI TIS%20 • Little, James and Falace, Donald. 1997. Dental Management of the Medically Compromised Patient. St. Louis, Missouri: Mosby, Inc. • Patient UK. “Infective Endocarditis.” EMIS and PIP 2004. Retrieved February 10, 2006 from http://www.patient.co.uk/showdoc/27000162/ • Roldan, Carlos A. 2005. The Ultimate Echo Guide. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. • Texas Heart Institute. “Infective Endocarditis.” Heart Information Center 2005. Retrieved February 1, 2006 from http://www.tmc.edu/thi/endocard.html