* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download ats1371_2015_tutorial_week10_small

Utilitarianism wikipedia , lookup

Business ethics wikipedia , lookup

Lawrence Kohlberg's stages of moral development wikipedia , lookup

Morality throughout the Life Span wikipedia , lookup

Virtue ethics wikipedia , lookup

Consequentialism wikipedia , lookup

Peter Singer wikipedia , lookup

Morality and religion wikipedia , lookup

Moral responsibility wikipedia , lookup

Critique of Practical Reason wikipedia , lookup

Thomas Hill Green wikipedia , lookup

Ethics in religion wikipedia , lookup

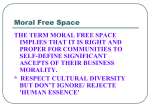

ATS1371 Life, Death, and Morality Semester 1, 2015 Dr Ron Gallagher [email protected] Tutorial 10 – Virtue Ethics and Ethical Relativism (1 more to go) GOOD FRIDAY NO TUTORIAL DON'T FORGET Weekly Reading Quizzes (x 10 @ 0.5% bonus each) Mondays 10am, weeks 2-11. Note: The section you need to read for the quiz is the one indicated for the week beginning the day the quiz is due. (Not the week just gone past.) Assessment Summary Within semester assessment: 60% Exam: 40% Assessment Task Short Answer Questions: AT1.1:(5%), 400 words due Wed 18th March AT1.2:(10%), 400 words due Wed 15th April AT1.3:(15%), 600 words due Wed 6th May AT2: Essay (30%), @1250 words due Wed 20th May Weekly Reading Quizzes (x 10 @ 0.5% bonus each) Mondays 10am, weeks 2-11. Examination (40%) Essay Guidelines (from Moodle) For the essay topics, it is not necessary that you do any additional research outside of the prescribed readings. If you wish to do additional research, that is fine, but please note that most philosophy essays suffer from not enough attention being paid to thinking, writing and drafting. You cannot make up for this by just doing more reading! Also note that plagiarism will be treated very severely if it is detected. Also note that it is possible to plagiarise unintentionally. So make sure you know how to avoid plagiarism by properly citing your sources and properly indicating where you are directly quoting. See the ‘Reference and Citation’ link under ‘Resources’ on Blackboard homepage. In your essay, you should try to fulfill the following requirements, especially the first: The essay must address the question asked. It should have a structure that is clear and organised to form a coherent argument. You should explain, in your own words, views and arguments in the prescribed readings that are relevant to the topic. Be careful to present these views fairly and accurately, with adequate citation detail. You should try to evaluate the arguments you have discussed, and in the process work out your own position. When you criticise a philosopher, try to think how (s)he might reply to your objections. You should give the full wording of the question before you begin your essay. You must carefully identify all connections between your essay and the writings of others. See 'Rules for Written Work' in the Information Sheets (which are available here in MUSO). Feedback If you would like some feedback on your essay in the planning and drafting stage your tutor can give limited feedback on an essay outline only. (Don’t send me a draft/outline 2 days before the essay is due) Marking criteria There are three main things we judge an essay on: First, we will be looking to see some evidence that you understand the issues you are writing about. This is really the most fundamental criterion and necessary if you are to pass. Second, the quality of the writing and organisation of the essay are quite important (this includes, grammar, spelling and proofreading). Third, the quality of your argument is also important. At first year level, this criterion is probably the least important, but only by a small margin! As you get to later year levels, it becomes increasingly important. ESSAY FAQs • The word limit is +/- 10% of 1250 words. • Direct quotations do not count towards the word count. • You are required to use at least one of the readings (not just the commentary or lecture slides) from the LDM Reader as your primary text. • You can reference the LDM Reader by page number, eg (Hobbes, 1651, LDM Reader p.156), you do not need to use the original page numbers of the individual papers in the Reader. The essential thing about a reference is that it enables your reader to find the source. To avoid plagiarism – always provide a reference. • Begin the essay with a statement of YOUR thesis (eg You that believe Otsuka’s restrictive account of self-defence is too restrictive that Thomson’s account is more intuitive/logical/useful.) and how you are going to support your claim with arguments from the LDM Reader. Questions for AT2: Essay (30%), @1250 words due Wed 20th May 1. Is it justified to kill an innocent threat in defence of oneself or others? Why/why not? Discuss, with reference to the views of at least two authors from the unit. 2. The principle of equality that Singer defends has radical consequences. Critically discuss the principle, explaining some of its consequences, and assess whether Singer is right that we ought to adopt it. 3. “Abortion is impermissible, because it deprives a being of a future like ours. Accordingly, it is morally similar to killing a healthy adult.” Critically discuss this argument, drawing upon at least one of the authors we have looked at in the readings. (You may assess the argument Marquis provides in support of this or the arguments from Thomson which oppose this.) 1. Is it justified to kill an innocent threat in defence of oneself or others? Why/why not? Discuss, with reference to the views of at least two authors from the unit. Weeks 5 & 6 Lectures Define your terms:Innocent, Doctrine of Double effect, right-to-life, rights violations, infringements, etc THOMSON’S ‘KILLING’ THEORY CONDITION* If you don’t harm X, X will kill you. OTSUKA’S ‘KILLING’ THEORY CONDITION* If you don’t harm X, X will be morally responsible for killing you. CLASSIC UTILITARIANISM Best consequences - maximise happiness- minimise pain PREFERENCE UTILITARIANISM Best consequences - Satisfy preferences – “my interests cannot count more than the interests of others” HOBBES State of nature, self-preservation, social contract *Whenever the condition is true of someone, you may harm them in self-defence. 2. The principle of equality that Singer defends has radical consequences. Critically discuss the principle, explaining some of its consequences, and assess whether Singer is right that we ought to adopt it. What is the POE? Does Singer’s POE have radical consequences? If yes, what are they? Who says they are radical consequences? What makes the consequences radical? What reason do we have to adopt the POE or not? Define your terms:Equality Egalitarian Radical Consequences (examples) Persons Preferences/Interests Singer describes the POE as a ‘minimally egalitarian principle’ It doesn’t recommend equal outcomes, but equal interests being considered equally. Egalitarianism (derived from the French word égal, meaning equal) or Equalism is a political doctrine that holds that all people should be treated as equals and have the same political, economic, social, and civil rights.[1] Singer on Preference Utilitarianism For preference utilitarians, taking the life of a person will normally be worse than taking the life of some other being, since persons are highly future-oriented in their preferences. To kill a person is therefore, normally, to violate not just one, but a wide range of the most central and significant preferences a being can have. Very often, it will make nonsense of everything that the victim has been trying to do in the past days, months, or even years. (Singer 1993, 95) “My own needs wants and desires cannot, simply because they are my preferences, count more than the wants needs and desires of anyone else. Thus, my very natural concern that my own wants, needs and desires – henceforth I shall refer to them as “preferences” – be looked after must, when I think ethically, be extended to the preferences of others.” Singer, Practical Ethics, p11-12. “The preference utilitarian has a rich repertoire of reasons available for not killing a PERSON. Not only is it the case that most people have a preference for continued life that ranks very high in their concerns, but also, because very many of the preferences people have are oriented toward the future – think of all the plans, intentions, desires and hopes that a normal person has for fulfilment in the future – killing someone must count, for a preference utilitarian, as possibly the worst harm one can do someone.” LDM Reader p.20 3. “Abortion is impermissible, because it deprives a being of a future like ours. Accordingly, it is morally similar to killing a healthy adult.” Critically discuss this argument, drawing upon at least one of the authors we have looked at in the readings. (You may assess the argument Marquis provides in support of this or the arguments from Thomson which oppose this.) See Week 9a Lecture for Marquis/Thomson comparison. See Singer Practical Ethics 141-143 for Marquis/Singer debate. You should address the logical argument against potentiality (e.g. the Prince Charles argument). How does Marquis get around the ‘Prince Charles argument?) Define your terms:Person, Human Being, Embryo, Foetus, Abortion, Totipotency, Potential, Innocent Singer - Only persons have a ‘right to life’ and foetus’s and young infants aren’t persons. Other things being equal, it is not seriously wrong to kill a being who does not have a significant interest in living. Thomson - The right to life does not constrain us to provide whatever is necessary for someone to live. Aborting the foetus may not infringe its right to life, but we may be obliged not to abort it. Marquis Killing a foetus deprives it of a future life like ours. Warren – The change from being in the womb to outside the womb is not simply a change of house. Birth marks the coming into existence of morally relevant relational properties. Pragmatic considerations mark birth as the right moment to attribute the rights of personhood. Not a person whilst ‘sharing skin of mother. Thomson’s account avoids having to resolve the question of whether the foetus has a right to life. •The case for abortion in the case of rape, or where pregnancy threatens the mother’s life, is much stronger in light of Thomson. Singer, in Practical Ethics, argues that if one made a small alteration to the Violinist scenario, Thomson’s argument covers accidental and ‘careless’ pregnancies as well. •Thomson deals with the question of whether it would be wrong to abort after 18 weeks (consciousness issue). The Violinist is a person with actual potential. Thomson does give us some distinction between abortion and infanticide because, post-birth, the foetus in no longer in the mother’s body. Abortion and Infanticide: Peter Singer debates Don Marquis https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Qfiq18DMYk 4 mins sanctity of life 28 mins onwards What is the difference between abortion and infanticide? Why is birth a morally significant demarcating line? VIRTUE ETHICS Where rights-based and CONSEQUENTIALIST theories call upon us to focus on the kinds of actions we ought to perform, virtue based theories ask us to concentrate on the kinds of people we ought to be. We ought to develop the virtues – excellences of character – within ourselves. In the Western tradition, virtue ethics is generally traced back to the work of Aristotle (384–322 BCE); in the Eastern tradition, Confucius developed and important virtue ethics. LDM Reader, P.212 VIRTUE ETHICS Virtue ethics is currently one of three major approaches in normative ethics. It may, initially, be identified as the one that emphasizes the virtues, or moral character, in contrast to the approach which emphasizes duties or rules (deontology) or that which emphasizes the consequences of actions (consequentialism). Suppose it is obvious that someone in need should be helped. A utilitarian will point to the fact that the consequences of doing so will maximize well-being, a deontologist to the fact that, in doing so the agent will be acting in accordance with a moral rule such as “Do unto others as you would be done by” and a virtue ethicist to the fact that helping the person would be charitable or benevolent. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ethics-virtue/ Ethical Relativism and Cultural Relativism RELATIVISM in ethics, the doctrine that the rightness and wrongness of actions varies from place to place, time to time, and perhaps even between individual persons. Most ethical relativists are cultural relativists; that is, they hold that the rightness of actions is relative to cultures. Ethical relativism is distinct from the idea that we ought not to criticise other cultures for their moral beliefs, but these ideas are often found together. LDM Reader, P.211 Question from Sample Exam (on Moodle) Rights, utilitarianism, and trolleys 1. What is the idea of stringency for a right? Illustrate the idea with two different rights that might be of different stringency. 2. What should a utilitarian think about rights? Do rights really exist? Would it ever be justified, for a utilitarian, to respect rights, even if that led to a worse outcome overall? 3. What is Thomson’s preferred account of why it is permissible to pull the lever in TROLLEY? Does the account succeed? 4. Utilitarians seem to be committed to some surprising conclusions about the morality of killing. Illustrate one or two of these conclusions, and try to explain why the utilitarian has such a surprising view. Question from Sample Exam (on Moodle) Self-defence 5. Describe Michael Otsuka’s position with respect to using violence in self-defence against innocent persons. Explain his reasons for his view. 6. “Killing an innocent threat in self-defence is wrong, but excusable”. Explain this claim, and discuss its plausibility. 7. What is the Hobbesian rationale for a liberty-right to engage in self-defence? What will the Hobbesian likely think about harming innocent threats in self-defence? Speciesism, animals, and equality 8. What is Singer’s “principle of equality”? How would our behaviour towards animals have to change if we were to adopt this principle? Why? 9. Does the principle of equality give a good explanation of what is wrong with racism? Why/why not? 10. For Singer, the morality of taking an animal’s life depends in part on whether the animal is a person. Explain why this makes a difference. Question from Sample Exam (on Moodle) Abortion 11. “Conventional liberal views on abortion are untenable. Either we must accept that infanticide is no worse than abortion, or we must adopt a very conservative anti-abortion view.” Discuss why a philosopher might think this is true. 12. “Judith Thomson’s violinist case shows only that women have a right to remove a fetus from their bodies. Therefore her argument is not a successful defence of abortion.” — Discuss both of the following: (i) Why might someone say this? (ii) Is this view correct? 13. Discuss the idea that abortion is wrong because of the potential properties possessed by the fetus (such as the potential for personhood, or autonomy, or some other morally significant property). Does this idea provide a good reason to think that abortion is morally wrong? Question from Sample Exam (on Moodle) Cultural relativism and moral methodology 14. How would you characterise the difference between virtue ethics and the approaches we have been looking at in most of the unit? 15. Is there a conflict between the virtue of being a good parent and the principle of equality? Explain your answer. 16. What is cultural relativism? If cultural relativism is true, does it have any implications for how we should treat people from other cultures? In particular, should we be tolerant of people from other cultures? 17. “If moral relativism is true, then people who appear to disagree with one another about morals are actually talking past one another”. Explain this claim. Is this a good objection to moral relativism? The difference between individual and cultural relativism: both views hold there is not objective right and wrong . Cultural relativism holds that ethical values vary from society to society and that the basis for moral judgements lies in these social cultural views. Individual relativism holds that ethical values are the expression of the moral outlook of the individual. Problems for cultural Relativism With which group should my views coincide? My extended family, state, culture etc? Different groups to which I belong can morally disagree. If society changes its views, why should this change morality? If 52 percent support a war but later only 48 percent do, why should this change the war’s claim to justice? Problem for both cultural and individual relativism Both seem to imply that relativism is more tolerant than objectivism, but in neither case is this true. A cultural relativist can hold that tolerance is good only insofar as tolerance is already a virtue in a given society. There is no reason for intolerant societies to change. Similarly, an individual relativist has no reason to listen to the different views and arguments of others, for there is no reason to think such views are objectively superior. Problem for individual relativism Individual relativism suggests morality is relative to my perspective as an individual. But what if I am inwardly conflicted on a moral question? Either I’m doing something wrong—which is hard to reconcile with individual relativism—or individual relativism cannot tell me what I ought to believe Mansfield Ruling on Slavery in England 1772 On behalf of Somersett, it was argued that while colonial laws might permit slavery, neither the common law of England, nor any law made by Parliament recognised the existence of slavery, and slavery was therefore illegal.[64] Moreover, English contract law did not allow for any person to enslave himself, nor could any contract be binding without the person's consent. The arguments thus focused on legal details rather than humanitarian principles.[64] A law passed in 1765 said that all lands, forts and slaves owned by the Africa Company were a property of the Crown, which could be interpreted to mean that the Crown accepted slavery.[64] When the two lawyers for Charles Stewart put their case, they argued that a contract for the sale of a slave was recognised in England, and therefore the existence of slaves must be legally valid.[64] After the attorneys for both sides had given their arguments, Mansfield called a recess, saying that "[the case] required ... [a] consultation ... among the twelve Judges".[66] Finally, on 22 June 1772 Mansfield gave his judgment, which ruled that a master could not carry his slave out of England by force, and concluded: The state of slavery is of such a nature, that it is incapable of being introduced on any reasons, moral or political; but only positive law, which preserves its force long after the reasons, occasion, and time itself from whence it was created, is erased from memory: it's so odious, that nothing can be suffered to support it, but positive law. Whatever inconveniences, therefore, may follow from a decision, I cannot say this case is allowed or approved by the law of England; and therefore the black must be discharged.[67] This was not an end to slavery, as this only confirmed it was illegal in England and Wales, not in the rest of the British Empire.[67] As a result of Mansfield's decision, between 14,000 and 15,000 slaves were immediately freed in England, some of whom remained with their masters as paid employees.[67] The decision was apparently not immediately followed; Africans were still hunted and kidnapped in London, Liverpool and Bristol to be sold elsewhere.