* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Government in Mesopotamia

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

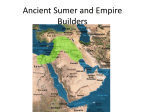

Form of Government in Mesopotamia The “land between the rivers” went through different forms of government which is understandable considering that the history of Mesopotamia encompasses almost 3 millenniums. Form of government from the emergence of Sumerian Civilization to Persian Empire did not did not only changed through time but it was also greatly influenced by different patterns of peoples who ruled Mesopotamia. History of Mesopotamia is characterized by frequent invasions and conquests of foreign peoples who established their own forms of government although they often only continued the established forms. Sumer, the first civilization in Mesopotamia and the oldest known in the world consisted of citystates. Rulers of Sumerian city-states (by Sumerians called en , lugal or ensi ) were both secular and spiritual rulers. In contrary to Egyptians pharaohs, Sumerian priest-kings were not viewed as divine but as human representatives of patron gods of city-states and lived in temples which were both religious and administrative centers of Sumerian city-states. Akkadians formed new form of government which became a model for later rulers although priesthood played very important role throughout the history of Mesopotamia. Akkadian kings were “classical” despots and had an absolute power, while the title was hereditary although usurpers seized the throne and established new ruling dynasties from time to time. Akkadian rulers named themselves Lord of the Four Quarters (of the Earth) and were eventually elevated to the divine status. Unlike in ancient Egypt, the divine status of the Mesopotamian rulers was more of an exception than the rule. Despotic form of government established by the Akkadians was adopted by the Amorite rulers who founded the first Babylonian Dynasty which reached its height during the reign of Hammurabi (c. 1792 - c.1750 BC). Babylonian kings also retained centralized administration introduced during the Akkadian Period, while the famous Code of Hammurabi indicates that the Babylonian kings had supreme legislative and jurisdictional authority. The Kingdom of Mitanni founded about 1500 BC in northern Mesopotamia was a feudal state with hierarchically organized society. Under the king who was the supreme authority was warrior nobility which received land as inalienable fiefs. Feudalism became predominant form of government throughout the ancient Near East by the middle of 2nd millennium BC. Assyria which was for a long period overruled by the Mitanni Kingdom was characterized by greatly militarized society which is probably a result of its struggles for independence and later expansionist policy. Assyrian Empire was ruled by despotic kings who had absolute power, while the structure of society remained feudal. Assyrians collected heavy taxes from subjugated peoples but they were probably best known for mass deportations of defeated peoples. Assyrian practice of deportation of defeated or rebellious peoples was also popular method in the Neo-Babylonian Empire which emerged as the leading power in the Middle East after the fall of Neo-Assyrian Empire in 612 BC. The practice of mass deportations ceased with the emergence of the Persian Empire under Achaemenid dynasty which became the leading power in the Middle East during the reign of Darius I (522-486 BC). The power of Achaemenid Empire primarily based on strong and powerful rulers, while large territorial extent required good administration. Persian Empire was divided into satrapies, provinces governed by satraps who were named by Achaemenid kings and supervised by king’s representatives. There were some great differences between forms of government in Mesopotamia in different periods but all forms of government from Sumer to the Persian Empire were characterized by powerful rulers who played a major role throughout the history of Mesopotamia. Forms of government as wells as all segments of life in ancient Mesopotamia was also greatly influenced by religion in name of which governed all Mesopotamian rulers. Law in Mesopotamia One of the greatest achievements of Mesopotamians are the first written codified laws which reveal the level of social, political, economical and legal development of the Mesopotamian civilization. Law in Mesopotamia is frequently closely associated with Code of Hammurabi inscribed on seven foot and four inch (2,25 meter) tall stela discovered at Susa but the oldest law codes date from the Sumerian Period. The oldest example of a legal code is attributed to Urukagna who ruled the Sumerian city-state of Lagash in the 24th century BC although the actual text has never been discovered. The Code of Ur-Nammu created by Ur-Nammu of Ur (21s century BC) is the oldest known code of law which is only partly preserved. The laws were inscribed on a clay tablet in Sumerian language and arranged in casuistic form, a pattern in which a crime is followed by punishment which was also the basis of nearly all later codes of law including the Code of Hammurabi. Code of Ur-Nammu is also notable for instituting monetary compensations for inflicting bodily injuries which is considered very advanced for the oldest known code of law. In contrary to Code of Ur-Nammu, the Code of Hammurabi from the 18th century BC bases on principle “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth” (lex talionis). One of the most famous ancient codes contains 282 judgements of civil and criminal law. The penalties vary from crime to crime as well as on the social status of the offender although even slaves had some rights. Hittite cuneiform tablets from the 14th century BC found at Hattusa also include number of Hittite laws which foresee less severe penalties than the Babylonian code of laws. Penalties were in some cases were even reduced at least twice. Hittite laws also reveal a tension to more systematical arrangement from the most serious to minor violations. The Hittites did not follow lex talionis. With rise of Assyria also occurred changes in penal laws which were severer and more brutal. Death penalty and corporal penalties such as flogging and cutting of ears and noses were very common, while forced labour was the most common punishment for less sever violations. Besides severer penalties the Assyrian law also reflects great change of social position of women. Women in Babylon and Hittite Empire were practically equal to men and were even allowed to divorce, while a man in Assyria was allowed to kill his wife if she committed adultery and to send his wife away without divorce money. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=77q4VpxxxDE&feature=related