* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

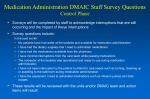

Download Visions 4.2 - Medications

Pharmaceutical industry wikipedia , lookup

Prescription costs wikipedia , lookup

Neuropharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Polysubstance dependence wikipedia , lookup

Prescription drug prices in the United States wikipedia , lookup

Neuropsychopharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Pharmacogenomics wikipedia , lookup

Psychopharmacology wikipedia , lookup