* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download MJP 2008, Vol.17 No - Malaysian Journal of Psychiatry

Victor Skumin wikipedia , lookup

Political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union wikipedia , lookup

Dissociative identity disorder wikipedia , lookup

Mentally ill people in United States jails and prisons wikipedia , lookup

St Bernard's Hospital, Hanwell wikipedia , lookup

Mental status examination wikipedia , lookup

Psychiatric rehabilitation wikipedia , lookup

History of psychosurgery in the United Kingdom wikipedia , lookup

Mental disorder wikipedia , lookup

Community mental health service wikipedia , lookup

Thomas Szasz wikipedia , lookup

Sluggish schizophrenia wikipedia , lookup

History of electroconvulsive therapy in the United Kingdom wikipedia , lookup

Causes of mental disorders wikipedia , lookup

David J. Impastato wikipedia , lookup

Mental health professional wikipedia , lookup

Psychiatric and mental health nursing wikipedia , lookup

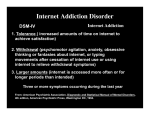

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders wikipedia , lookup

Cases of political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union wikipedia , lookup

Classification of mental disorders wikipedia , lookup

Moral treatment wikipedia , lookup

Deinstitutionalisation wikipedia , lookup

Anti-psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Political abuse of psychiatry in Russia wikipedia , lookup

Critical Psychiatry Network wikipedia , lookup

Death of Dan Markingson wikipedia , lookup

Emergency psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Abnormal psychology wikipedia , lookup

History of mental disorders wikipedia , lookup

Political abuse of psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Psychiatric survivors movement wikipedia , lookup

Psychiatric hospital wikipedia , lookup

History of psychiatric institutions wikipedia , lookup

History of psychiatry wikipedia , lookup