* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Granulomatous Meningoencephalomyelitis in Dogs

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

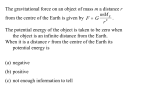

644 Vol. 23, No. 7 July 2001 Email comments/questions to [email protected] or fax 800-556-3288 CE Article #3 (1.5 contact hours) Refereed Peer Review Granulomatous Meningoencephalomyelitis in Dogs KEY FACTS Louisiana State University ■ Acute-onset blindness is the most common manifestation of ocular granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis due to optic neuritis. ■ Cytologic evaluation of cerebrospinal fluid generally reveals a nonsuppurative inflammation; however, a high number of neutrophils may be seen in some cases. ■ The immunosuppressive drug leflunomide may be a reasonable alternative treatment in steroidsensitive dogs. Kirk Ryan, DVM Steven L. Marks, BVSc, MS, DACVIM Sharon C. Kerwin, DVM, MS, DACVS ABSTRACT: Granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis (GME) is an acute, progressive disease causing focal to multifocal neurologic signs or sudden blindness in dogs. Typically, GME affects middle-aged, small-breed dogs. Classic histologic findings include perivascular cuffs of mononuclear inflammation in the brain and spinal cord with a predilection for white matter. A tentative diagnosis of GME is based on supportive history, physical examination, cerebrospinal fluid analysis, and cross-sectional imaging of the brain or spinal cord. This diagnostic testing is also indicated to exclude the diagnosis of similarly presenting infectious, inflammatory, and neoplastic diseases. Confirming a diagnosis of GME requires histologic examination of the central nervous system via brain biopsy or at necropsy. Corticosteroids remain the mainstay of therapy. However, radiation therapy and new immunosuppressive drugs may induce a transient remission of clinical signs. Currently, the prognosis for prolonged recovery is poor. Recurrence and progression of neurologic signs frequently result in death or necessitate euthanasia. G ranulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis (GME) is an inflammatory disease of unknown etiology that affects the central nervous system (CNS) of dogs. It is a common diagnostic differential for dogs with focal or multifocal neurologic disease. The description of GME in the veterinary literature frequently overlaps with that of reticulosis (Box 1), a broad category of historically important infiltrative CNS diseases. Clinical signs vary and depend on the neuroanatomic location of the lesions. Although largely considered an inflammatory disease, several different etiologies have been hypothesized. The histopathologic lesions of GME share features with infectious, neoplastic, and immune-mediated diseases. PATHOLOGY Histopathology remains the basis of our current understanding of GME. Classic GME lesions are characterized by perivascular cuffs of proliferating monocytes, macrophages, lymphocytes, and plasma cells (Figure 1).1–5 These perivascular cuffs often merge at adjacent vessels to form cellular whorls, which evolve into nodular granulomas that mimic space-occupying masses.1,3,4,6 Occasionally, Compendium July 2001 Small Animal/Exotics 645 BOX 1 Reticulosis The term central nervous system (CNS) reticulosis is used to describe a group of neoplastic and idiopathic inflammatory diseases of the reticuloendothelial system of the CNS (including GME).11,16–18,20 The definition of reticulosis emphasizes the shared perivascular orientation and histiocytic appearance of lesions in this group of diseases.18 However, some confusion exists in the literature regarding the proper designation of these diseases. Although a few sources distinguish inflammatory reticulosis from neoplastic reticulosis,11,16 many cases previously designated only as reticulosis are probably cases of GME.21 Inflammatory reticulosis (focal and multifocal) has been distinguished from GME (disseminated) on the basis of lesion distribution.18 Occasionally, the term reticulosis is used primarily to refer to neoplastic diseases.12 The use of terms such as neoplastic GME and inflammatory GME is characteristic of the overlapping definitions found in the literature.15 This confusion highlights the difficulty in clinically differentiating GME from similar neoplastic and inflammatory CNS lesions. Neoplastic processes can incite a significant inflammatory response. Chronic, severe inflammation may take on histopathologic characteristics of neoplasia. Recently, immunohistochemical studies have been used to further classify the inflammatory cells within GME lesions.5,22 One such study concluded that GME may be an immunemediated disease caused by a T-cell–mediated, delayedtype hypersensitivity reaction to CNS antigens.5 Likewise, some cases of reticulosis have been further classified as primary lymphomas of the brain.22 This debate over disease classification is clinically relevant because the key to effective treatment is accurate diagnosis. granulomas develop that are not associated with blood vessels.1,3 Rarely, the inclusion of neutrophils within lesions has been described.2,4 In general, classic perivascular cuff lesions of varying severity are found throughout the brain and cervical spinal cord.1,2 GME lesions have been localized to the eye, cerebrum, brain stem, cerebellum, and cervical spinal cord.1,2,4,7–10 Within the CNS, lesions generally affect the white matter more than the gray matter.1,3,11,12 Meningeal inflammation has been reported in association with underlying lesions.5 Microscopically, ophthalmic GME is characterized by marked nonsuppurative inflammatory infiltrates and granuloma formation within the optic nerve from the optic disk to the optic chiasm.13,14 Similar lesions may be noted in the retina and choroids.14–17 Retinal atrophy with accumulation of pigment and adhesions to the underlying choroid may also occur.13,14 Occasionally, classic perivascular lesions may extend into the sclera.15,17 The origin of inflammatory cells in GME is controversial. These cells may result from the migration of blood-derived inflammatory cells or, more likely, represent a proliferative reaction within the CNS reticuloendothelial system.1,5,6 Regardless of origin, these cells accumulate in the space surrounding the vessels that penetrate the brain (Virchow-Robin space).6,18,19 This space is outlined by perivascular invaginations of the pia mater around small vessels entering the brain and is normally lined with a low number of reticuloendothelial cells.19 The normal reticuloendothelial cells of the CNS include microglia and blood-derived monocytes.12 CLINICAL SIGNS Clinical signs vary with the location and severity of GME lesions. In general, GME should be suspected in any mature dog that develops progressive signs of focal or multifocal neurologic dysfunction, including the following4,23,24: ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Seizures Depression Blindness Head tilt Circling ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ Cranial nerve dysfunction Weakness Ataxia Cervical pain Proprioceptive deficits SYNDROMES Focal GME lesions mimic space-occupying masses (Figure 2). Clinical signs of focal disease occur secondary to nodular granuloma formation, but these cases may have disseminated lesions as well.3,4 The focal form of GME may have a slower onset and progression (3 to 6 months) than disseminated GME.1 Figure 1—Photomicrograph demonstrating the classic histo- logic lesion of granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis. 646 Small Animal/Exotics Compendium July 2001 Figure 2—Sagittal brain sections demonstrating the extent of a Figure 3— Optic neuritis consistent with granulomatous gross granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis lesion (arrows). meningoencephalomyelitis. Multifocal or disseminated GME progresses more rapidly and is reported to have an acute onset (2 to 6 weeks) with more varied clinical signs.1 Some authors have attempted to loosely define a number of clinical syndromes associated with the location of lesions or disease progression.1,4,16 One author reported five clinical syndromes associated with focal lesions in the cerebrum, midbrain, pons/medulla, vestibular system, and cerebellum.1 The clinical relevance of these syndromes has been questioned because many cases present with multifocal neurologic signs.3 Ocular manifestations of GME have been well recognized and documented in the literature.13–15,17 Frequently, this syndrome is characterized by acute blindness with some cases later developing neurologic signs with CNS lesions.8,13–17 The acute blindness is attributed to optic neuritis characterized by dilated pupils, no menace response, and no pupillary light response.13,14,17 Severe anterior and posterior uveitis may also occur.15 Acute signs of optic neuritis that may be recognized during ophthalmic examination include swollen elevated optic disks with blurred margins, hyperemia, and no physiologic cup (Figure 3).11,13,14,17 In more chronic cases, optic nerve atrophy may be evidenced by a shrunken optic disk with gray discoloration.13 Retinal detachment and petechial hemorrhage may also be noted during fundic examination.14 GME usually affects both eyes but may be unilateral.18 on signalment and clinical signs facilitates the diagnosis of GME. Although any age and breed may be affected, the disease classically affects middle-aged, small-breed dogs (Figure 4).1,3,8,23 Male and female dogs appear to be equally affected based on inconsistent reports of sex predilection.1,3,8,23 An appropriate diagnostic plan leading to a definitive diagnosis of GME includes laboratory testing, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, advanced imaging, and histopathologic confirmation. Common laboratory tests (e.g., complete blood cell count, serum chemistry, urinalysis) are often within normal limits because GME is not usually a multisystemic disease.1,3,15 Complete blood cell count results consistent with both inflammation and stress have been reported.4,25 Cerebrospinal fluid analysis represents one of the most important diagnostic tests for GME because it is readily performed and frequently abnormal. However, mild disease may not disrupt the blood–brain barrier enough to allow exfoliation of cells into the CSF.16 Classic CSF abnormalities include a mononuclear pleocytosis with elevated protein (mostly globulin) concentration. 1,3,8,23,24 Lymphocytes and macrophages are the predominant cell types with a variable number of mononuclear cells (Figure 5).1–3,8,23,24 Dogs with GME may have a significant number of neutrophils in the CSF and may also demonstrate polymorphonuclear cells within classic lesions.3,23,24 In one study of 22 dogs with GME, total CSF leukocyte counts ranged from 9.0 to 5400 cells/µl (normal, less than 10 cells/µl), while CSF protein ranged from 13.0 to 1119 mg/dl (normal, less than 25 mg/dl).24 In this study, abnormalities were more DIAGNOSIS The clinical signs of GME are not pathognomonic, and a number of diagnostic differentials (Box 2) must be considered. A high level of clinical suspicion based Compendium July 2001 Small Animal/Exotics 647 BOX 2 Diagnostic Differentials A diagnosis of GME is supported by the exclusion of neoplastic, infectious, and inflammatory central nervous system (CNS) diseases causing similar clinical signs. A variety of infectious diseases are included on the list of diagnostic differentials. A few of these merit specific attention. It has been suggested that GME is caused by an as yet unidentified infectious agent.21 Viral encephalitides (e.g., rabies and distemper) are important considerations, especially in unvaccinated pets from endemic areas. Distemper virus has been associated with encephalitis of mature dogs and may be capable of persistent, latent infection.28 CNS lesions associated with canine distemper virus are characterized in part by mononuclear perivascular cuffing and a predilection for white matter that mimics the lesions of GME.29,30 GME cases have been reported with rabieslike or distemperlike inclusion bodies.31 In fact, distemper virus was once considered a likely etiologic agent for GME based on a case report demonstrating large amounts of distemper virus antigen within classic GME lesions.32 In general, a diagnosis of distemper is confirmed by demonstration of viral antigen in brain tissue by immunohistochemistry.29 Positive cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) distemper titers provide strong supportive evidence but may be negative in some cases of distemper encephalitis.25,30 False-positive CSF titers may be obtained in association with blood contamination of the CSF sample. In addition, CSF analysis in distemper often yields less dramatic pleocytosis (less than 25 cells/µl) than GME.24 Protozoal encephalomyelitis may occur secondary to infection with Toxoplasma gondii or Neospora caninum.33,34 Although affected animals may present with multifocal neurologic signs that mimic GME, these agents frequently cause clinical signs in other body systems as well.33,34 CSF abnormalities are nonspecific and include an elevated protein concentration and an increased nucleated cell count (predominantly lymphocytes and mononuclear cells).33,34 CSF and serum antibody titers may be useful in excluding this diagnosis. However, normal dogs may have high serum titers.33,34 Serologic tests may be performed on CSF samples, but their diagnostic value has not been completely evaluated.25 This is especially true when the integrity of the blood–brain barrier is in question. Cytologic marked in the cisternal CSF compared with the lumbar CSF. The effect of blood contamination and previous steroid therapy on CSF parameters is debatable but should be considered when normal CSF results are found in a patient with severe clinical disease.3,24 Prior identification of these organisms in the CSF is definitive, but the diagnosis is most commonly made at necropsy.33,34 Idiopathic breed-specific CNS inflammatory diseases are important diagnostic differentials.25 This is particularly true of the necrotizing meningitis seen in pugs, Maltese terriers, and Yorkshire terriers.35–37 Affected animals present with the classic signalment, clinical signs, and diagnostic test results associated with GME. These diseases generally progress despite therapy and carry a poor prognosis. Antemortem differentiation of GME from breed-specific necrotizing meningitis may be difficult without biopsy but may be clinically important as advances in the diagnosis and treatment of GME occur. Meningoencephalitis may occur secondary to infection with the yeast organism Cryptococcus neoformans.38 In endemic areas, this is an important consideration prior to initiating immunosuppressive therapy. Various cytologic abnormalities (i.e., pyogranulomatous and eosinophilic inflammation) have been reported in the CSF of dogs with cryptococcal meningitis.39 Ideally, the diagnosis is based on cytologic identification of characteristic yeast organisms in the CSF or other sites.39 In addition, the latex agglutination serologic test for Cryptococcus identifies capsular antigen.39 Consequently, a positive test result is indicative of an active infection; tests can be performed on serum and CSF samples.39 Neoplasia is one of the primary differential considerations in the diagnosis of GME. The classic inclusion of GME with neoplastic disease under the larger term reticulosis underscores the fact that these diseases can appear clinically and histologically very similar.11,12,16 The clinical signs and diagnostic imaging of certain neoplasms (e.g., meningioma) and focal GME parallel each other. Immunohistochemical evidence suggests that some cases diagnosed as focal GME are actually B-cell lymphoma or primary histiocytic neoplasia.22 Ideally, the neoplastic cell of origin should be determined by immunohistochemistry whenever a neoplastic process is suspected. Many diseases capable of causing optic neuritis (e.g., infectious, inflammatory, neoplastic, and idiopathic disease) are diagnostic differentials of ocular GME. steroid therapy has been suspected to decrease the diagnostic yield of CSF cytology.1 In at least one study, previous steroid therapy and/or blood contamination did not appear to interfere with the detection of pathologic changes.24 648 Small Animal/Exotics Figure 4—Toy-breed dogs represent the typical signalment for granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis. However, idiopathic breed-specific necrotizing meningoencephalitides are separate entities to be considered. Cerebrospinal fluid pressure measurement is occasionally performed at the time of sample collection. Both normal and increased values have been obtained and probably depend on the severity of the disease and the skill of the clinician performing the measurement.16,24 Rarely, CSF protein electrophoresis is performed to further identify increased proteins.4 At this time, such information does not appear helpful in the diagnosis and treatment of GME as disruption of the blood–brain barrier and leakage of serum proteins are hallmarks of the disease. Although a presumptive diagnosis of GME based on history, signalment, physical examination, and supportive CSF findings is often sufficient to begin treatment, advanced imaging and histologic confirmation are required to make a definitive diagnosis. Advanced imaging modalities identify lesions consistent with focal and multifocal GME.7,9,10 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has significant advantages over computed tomography (CT) when used for generating images of the brain. 9 Specifically, MRI images have greater anatomic detail and fewer artifacts associated with bony structures.9 In addition, MRI technology allows the production of images from any geometric plane.9 There are few published case reports documenting the advanced imaging of histologically confirmed GME. Contrast enhancement of focal GME lesions on CT has been reported.7,10 In a review of three cases diagnosed via CT, GME lesions were less enhanced than meningiomas following contrast administration.7 In another retrospective study, nonspecific CT abnormalities that correlated well with lesion localization included hydrocephalus, edema, falcial deviation, and asymmetry of ventricles.10 In a report of two GME cases confirmed histologically and by brain MRI, one dog had a focal lesion with features consistent with both inflam- Compendium July 2001 Figure 5—Photomicrograph of cerebrospinal fluid from a dog with granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis. Lymphocytes and macrophages are the prominent cytologic cell types. mation and neoplasia. 9 In T 1-weighted images, an isointense space-occupying mass was delineated by a hypointense margin. In T2-weighted images, the mass was hyperintense compared with surrounding normal brain tissue.9 The second dog developed an enhancing lesion that was not evident on T1- and T2-weighted images prior to contrast administration.9 Unfortunately, MRI and CT cannot always completely differentiate neoplastic from nonneoplastic diseases of the CNS.7,9,10 Although antemortem diagnosis of GME is possible, histologic confirmation of the diagnosis is often not obtained until necropsy. Surgical brain biopsy following MRI or CT has been described with varying rates of morbidity.7,8 Some of these cases involve dogs taken to surgery for excision of suspected neoplasia.7 In addition, CT-guided (free-hand or stereotactic) brain biopsy has been used in clinical cases to differentiate neoplastic from nonneoplastic disease.26,27 Tissue for microscopic examination should be obtained whenever possible (antemortem or postmortem). TREATMENT Central Nervous System GME Treatment may begin once a diagnosis of GME has been established. Corticosteroid therapy remains the standard treatment of GME despite eventual progression of clinical signs in most cases.1,3,8,23 Information regarding the dosage and efficacy of different corticosteroids in the treatment of GME is lacking. Many authors report the use of prednisone or prednisolone at a dose of 1 to 2 mg/kg sid or bid.1,16,17,23 In general, an immunosuppressive course of prednisone should be followed by a slow taper over 4 months until the lowest therapeutic dose is reached. Discontinuation of therapy is rarely achieved in true cases of GME. The use of cytotoxic agents is not routine. Cyclophosphamide, specifi- Compendium July 2001 cally, is poorly distributed to the CNS.40 Recently, leflunomide (Arava™, Aventis Pharmaceuticals, Bridgewater, NJ), a de novo pyrimidine synthesis inhibitor,41 has been used to treat immune-mediated and inflammatory diseases in dogs.42 Activated T lymphocytes synthesize pyrimidine primarily through the de novo pathway and may be especially sensitive to leflunomide.41 This information is noteworthy because GME may be a T-cell–mediated autoimmune disease.5 Although experience with this drug is still limited, it has been advocated in the treatment of certain CNS diseases in dogs that were experiencing severe side effects from glucocorticoid therapy.43 In humans, leflunomide has been associated with alopecia, diarrhea, and leukopenia.41 At the present time, the significant cost of this drug limits its use in many cases. Radiation therapy may be a useful treatment modality for some cases of GME.8,44 A definitive assessment of the efficacy of radiation therapy for cases of histopathologically confirmed GME is lacking. However, a recent report suggests that radiation therapy prolonged the survival of dogs with focal GME.8 In addition, complete resolution of clinical signs and CT scan abnormalities following radiation therapy has been reported in a small number of confirmed cases of GME.44 Absence of histologic GME lesions at necropsy has been reported in a small number of cases that had confirmatory antemortem brain biopsies followed by radiation therapy.8 Total doses of radiation ranged from 40.0 to 49.5 Gy.8,44 In one report, these doses were divided into 2.4- to 4.0-Gy fractions and administered via a 6mV linear accelerator or a cobalt-60 teletherapy unit.8 Complications of radiation therapy for CNS diseases include infarction, necrosis, cataracts, and keratoconjunctivitis sicca. 45 Infarction and resulting necrosis commonly manifest as seizures but may not be apparent for 5 to 6 months.45 The use of radiation therapy in nonneoplastic diseases is controversial, and the hazards of such therapy should be considered in addition to the potential benefit. Anticonvulsant agents may be valuable in select cases to control seizure activity.16,23 Diazepam at standard doses may be administered intravenously or per rectum to terminate ongoing seizure activity. Other drugs, such as phenobarbital and potassium bromide, may be used for maintenance anticonvulsant therapy. A thorough evaluation for other causes of seizures is indicated. Ocular GME The treatment of ocular GME is similar to that of CNS GME. Oral corticosteroids alone or in conjunction with locally administered corticosteroids have been used to induce remission of clinical signs.1,13,14,16,17 Ther- Small Animal/Exotics 649 apy for glaucoma and other sequelae to ocular inflammation may be necessary in conjunction with corticosteroid therapy. PROGNOSIS In general, GME has a poor prognosis.1,4,8,16,46 Among dogs with severe seizure disorders, pets diagnosed with GME are more likely to be euthanized or die during hospitalization.46 Disseminated GME reportedly has an acute onset and progresses rapidly to death or euthanasia within 6 weeks.1,16 The focal form of this disease may have a more insidious onset and progresses slowly over 3 to 6 months.1 In a recent study, dogs with focal GME had a median survival time of 114 days (range, 3 to more than 1215 days).8 Dogs with multifocal signs had a median survival time of 8 days (range, 1 to 274 days).8 Corticosteroid therapy may induce a transient remission of clinical signs and prolong survival in some patients.1,3,8,16 Positive prognostic indicators reportedly include clinical and histopathologic evidence of focal disease and treatment with radiation therapy.8 In ocular GME, the prognosis for permanent return of visual function is poor.13,14,17 However, transient improvements in vision may occur following corticosteroid therapy.13,14,17 In a recent report, ocular GME rarely progressed to a fatal neurologic disease.8 Other authors frequently cite ophthalmic signs in combination with severe neurologic impairment.13,14,16,17 CONCLUSION GME is a frequent consideration in the diagnosis of dogs with neurologic disease. A presumptive diagnosis is based on signalment, history, physical and neurologic examination, and supportive diagnostic tests or advanced imaging. Definitive diagnosis requires tissue sampling for microscopic evaluation via brain biopsy or postmortem examination. Immunohistochemical studies will most likely be the source of information needed to further our understanding of the disease. Standard treatments for GME consist of corticosteroids and anticonvulsants. Novel immunosuppressive drugs and radiation therapy are useful in some cases. Currently, the prognosis for prolonged recovery is poor. REFERENCES 1. Braund KG: Granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis. JAVMA 186:138–141, 1985. 2. Braund KG, Vandevelde M, Walker T, et al: Granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis in six dogs. JAVMA 172: 1195–1200, 1978. 3. Thomas J, Egger C: Granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis in 21 dogs. J Small Anim Pract 30:287–293, 1989. 4. Sorjonen D: Clinical and histopathological features of granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis. JAAHA 26:141–147, 1990. 650 Small Animal/Exotics 5. Kipar A, Baumgartner W, Vogl C, et al: Immunohistochemical characterization of inflammatory cells in brains of dogs with granulomatous meningoencephalitis. Vet Pathol 35:43–52, 1998. 6. Russo M: Primary reticulosis of the central nervous system in dogs. JAVMA 174:492–500, 1979. 7. Speciale J, VanWinkle T, Steinberg S, et al: Computed tomography in the diagnosis of focal granulomatous meningoencephalitis: Retrospective evaluation of three cases. JAAHA 28:327–332, 1992. 8. Munana K, Lutgen P: Prognostic factors for dogs with granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis: 42 cases (1982– 1996). JAVMA 212:1902–1906, 1998. 9. Lobetti R, Pearson J: Magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of focal granulomatous meningoencephalitis in two dogs. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 37:424–427, 1996. 10. Plummer S, Wheeler S, Thrall D, et al: Computed tomography of primary inflammatory brain disorders in dogs and cats. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 33:307–312, 1992. 11. Koestner A, Jones T: Malignant lymphoma or lymphosarcoma: Primary in central nervous system, in Jones T (ed): Veterinary Pathology, ed 6. New York, Williams and Wilkins, 1997, pp 307–309. 12. Jubb K, Huxtable C: The nervous system, in Jubb K, Kennedy P, Palmer N (eds): Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed 4. San Diego, Academic Press, 1993, pp 267–439. 13. Fischer C, Liu S: Neuro-ophthalmologic manifestations of primary reticulosis of the central nervous system in a dog. JAVMA 158:1240–1248, 1971. 14. Smith J, DeLahunta A, Riis R: Reticulosis of the visual system in a dog. J Small Anim Pract 18:643–652, 1977. 15. Smith R: A case of ocular granulomatous meningoencephalitis in a German shepherd dog presenting as bilateral uveitis. Aust Vet Pract 25:73–78, 1995. 16. Cuddon P, Smith-Maxie L: Reticulosis of the central nervous system in the dog. Compend Contin Educ Vet Pract 6:23–32, 1984. 17. Garmer N, Naeser P, Bergman A: Reticulosis of the eyes and the central nervous system in a dog. J Small Anim Pract 22:39–45, 1981. 18. Vandevelde M: Primary reticulosis of the central nervous system. Vet Clin North Am 10:57–63, 1980. 19. Braund KG: Encephalitis and meningitis. Vet Clin North Am 10:31–57, 1980. 20. Fankhauser R, Fatzer R, Luginbuhl H, et al: Reticulosis of the central nervous system (CNS) in dogs. Adv Vet Sci Comp Med 16:35–71, 1972. 21. Vandevelde M: Neurologic diseases of suspected infectious origin, in Greene C (ed): Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. Philadelphia, WB Saunders Co, 1998, pp 530–532. 22. Vandevelde M, Fatzer R, Fankhauser R: Immunohistological studies on primary reticulosis of the canine brain. Vet Pathol 18:577–588, 1981. 23. Sarfaty D, Carrillo J, Greenlee P: Differential diagnosis of granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis, distemper, and suppurative meningoencephalitis in the dog. JAVMA 188: 387–392, 1986. 24. Bailey C, Higgins R: Characteristics of cerebrospinal fluid associated with canine granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis: A retrospective study. JAVMA 188:418– 421, 1986. 25. Tipold A: Diagnosis of inflammatory and infectious diseases of the central nervous system in dogs: A retrospective study. J Vet Intern Med 9:304–314, 1995. Compendium July 2001 26. Koblik P, LeCouteur R, Higgins R, et al: CT-guided brain biopsy using a modified Pelorus Mark III stereotactic system: Experience with 50 dogs. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 40:434–440, 1999. 27. Harari J, Moore M, Leathers C, et al: Computed tomographic-guided, free-hand needle biopsy of brain tumors in dogs. Prog Vet Neurol 4:41–44, 1994. 28. Lincoln S, Gorham J, Davis W, et al: Studies of old dog encephalitis. Vet Pathol 10:124–129, 1973. 29. Palmer D, Huxtable C, Thomas J: Immunohistochemical demonstration of canine distemper virus antigen as an aid in the diagnosis of canine distemper encephalomyelitis. Res Vet Sci 49:177–181, 1990. 30. Thomas W, Sorjonen D, Steiss J: A retrospective evaluation of 38 cases of distemper encephalomyelitis. JAAHA 29:129–132, 1992. 31. Cameron A, Conroy J: Rabies-like neuronal inclusions associated with a neoplastic reticulosis in a dog. Vet Pathol 11:29–37, 1974. 32. Vandevelde M, Kristensen B, Greene C: Primary reticulosis of the central nervous system in the dog. Vet Pathol 15:673–675, 1978. 33. Dubey J: Toxoplasmosis in dogs. Canine Pract 12:7–28, 1985. 34. Ruehlmann D, Podell M, Oglesbee M, et al: Canine neosporosis: A case report and literature review. JAAHA 31:174–183, 1995. 35. Stalis I, Chadwick B, Dayrell-Hart B, et al: Necrotizing meningoencephalitis of Maltese dogs. Vet Pathol 32:230–235, 1995. 36. Tipold A, Fatzer R, Jaggy A, et al: Necrotizing encephalitis in Yorkshire terriers. J Small Anim Pract 34:623–628, 1993. 37. Cordy D, Holliday T: A necrotizing meningoencephalitis of pug dogs. Vet Pathol 26(3):191–194, 1989. 38. Berthelin CF, Bailey CS, Kass PH, et al: Cryptococcosis of the nervous system in dogs, Part 1: Epidemiologic, clinical, and neuropathologic features. Prog Vet Neurol 5:88–97, 1994. 39. Berthelin CF, Legendre AM, Bailey CS, et al: Cryptococcosis of the nervous system in dogs, Part 2: Diagnosis, treatment, monitoring and prognosis. Prog Vet Neurol 5:136–146, 1994. 40. Stanton M, Legendre A: Effects of cyclophosphamide in dogs and cats. JAVMA 188:1319–1322, 1986. 41. Smolen J, Kalden J, Scott D, et al: Efficacy and safety of leflunomide compared with placebo and sulphasalazine in active rheumatoid arthritis: A double-blind, randomized, multicentre trial. Lancet 353:259–266, 1999. 42. Gregory C, Stewart A, Sturges B, et al: Leflunomide effectively treats naturally occurring immune-mediated and inflammatory diseases of dogs that are unresponsive to conventional therapies. Proc 16th ACVIM Forum:716, 1998. 43. Sturges B, LeCouteur R, Gregory C, et al: Leflunomide for treatment of inflammatory or malacic lesions in three dogs: A preliminary clinical study. Proc 16th ACVIM Forum:697, 1998. 44. Sisson A, LeCouteur R, Dow S, et al: Radiation therapy of granulomatous meningoencephalomyelitis of dogs [abstract]. J Vet Intern Med 3:119, 1989. 45. Gavin P, Fike J, Hoopes P: Central nervous system tumors. Semin Vet Med Surg (Small Anim) 10:180–189, 1995. 46. Bateman S, Parent J: Clinical findings, treatment, and outcome of dogs with status epilepticus or cluster seizures: 156 cases (1990–1995). JAVMA 215:1463–1468, 1999. Compendium July 2001 ARTICLE #3 CE TEST The article you have read qualifies for 1.5 contact hours of Continuing Education Credit from the Auburn University College of Veterinary Medicine. Choose the best answer to each of the following questions; then mark your answers on the postage-paid envelope inserted in Compendium. CE 1. Which of the following is the treatment of choice for GME? a. corticosteroids b. vincristine and cyclophosphamide c. radiation therapy d. NSAIDs e. broad-spectrum antibiotics 2. By which of the following are GME lesions most commonly characterized? a. pyogranulomatous inflammation b. eosinophilic inclusion bodies c. retinal degeneration d. focal lesions of the thoracolumbar spinal cord e. nonsuppurative perivascular cuffing 3. Clinical signs of GME include which of the following? a. vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss b. lower motor neuron hindlimb reflexes c. seizures, head tilt, ataxia, blindness d. cervical pain, proprioceptive deficits e. c and d 4. A complete diagnostic plan for GME includes which of the following? a. an ophthalmic examination b. CSF analysis c. MRI or CT d. histologic confirmation e. all of the above 5. Which of the following radiographic studies is most useful in the diagnosis of GME? a. skull radiography d. MRI b. ultrasonography e. CT c. myelography 6. The term reticulosis (when discussing the CNS) refers to which of the following? a. accumulation of reticulin fibers with meningeal inflammation b. a group of diseases characterized by proliferation of cells associated with the CNS reticuloendothelial system (including inflammatory and neoplastic diseases) c. nonsuppurative inflammation of the thalamic reticular nucleus Small Animal/Exotics 651 d. an uncommon form of GME e. a degenerative disease of the peripheral nervous system 7. An idiopathic breed-related necrotizing meningitis that mimics GME has been reported in which of the following? a. whippets, greyhounds, salukis b. poodles, schnauzers, West Highland white terriers c. small, white, toy-breed dogs d. pugs, Maltese terriers, Yorkshire terriers e. golden retrievers, Labrador retrievers 8. Leflunomide is a. a classic NSAID. b. a chemotherapeutic agent. c. an alternative immunosuppressive agent. d. a dietary supplement. e. a potassium-sparing diuretic. 9. A worse prognosis for GME is associated with which of the following? a. focal GME b. cervical spinal cord GME c. multifocal GME d. ophthalmic GME e. treatment with radiation therapy 10. Ophthalmic GME is frequently characterized by which of the following? a. corneal opacity b. rapid progression and death c. acute blindness due to optic neuritis d. keratoconjunctivitis sicca e. retrobulbar granulomatous inflammation