* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia

Remote ischemic conditioning wikipedia , lookup

Electrocardiography wikipedia , lookup

Antihypertensive drug wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac contractility modulation wikipedia , lookup

Coronary artery disease wikipedia , lookup

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy wikipedia , lookup

Management of acute coronary syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Heart arrhythmia wikipedia , lookup

Quantium Medical Cardiac Output wikipedia , lookup

Ventricular fibrillation wikipedia , lookup

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia wikipedia , lookup

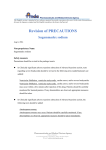

European Heart Journal (2004) 25, 1093–1099 Review Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia: where do we stand? Demosthenes G. Katritsis*, A. John Camm Department of Cardiology, Athens Euroclinic, 9 Athanassiadou Street, Athens 11521, Greece Department of Cardiological Sciences, St. George’s Hospital Medical School, London, UK KEYWORDS The clinical approach to the patient with nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT) should always be considered within the particular clinical context in which the arrhythmia occurs. In the documented absence of heart disease, spontaneous NSVT does not carry any adverse prognostic significance. Exercise-induced NSVT may predict increased cardiac mortality. In ischaemic patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF)<40%, NSVT has an adverse prognostic significance and electrophysiologic testing is indicated with a view to ICD implantation. In patients with LVEF>40% the independent prognostic significance of NSVT is unknown. The prognostic value of NSVT in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy is not known. NSVT in young patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy carries an adverse prognostic significance. The prognostic value of NSVT in conditions such as the long-QT syndromes, primary ventricular fibrillation, and Brugada syndrome, as well as in patients with hypertension and valvular disease, has not been established. c 2004 Published by Elsevier Ltd on behalf of The European Society of Cardiology. Ventricular tachycardia; Nonsustained Introduction Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT) is one of the most common problems encountered in modern clinical cardiology. The term, defined as 3 or more consecutive beats arising below the atrioventricular node with a rate >120 beats/min and lasting less than 30 s,1–3 denotes an electrocardiographic finding that can be associated with an extremely wide range of clinical conditions, from patients with significant heart disease and annual mortality rates exceeding 50% to asymptomatic, apparently healthy, young individuals. In several clinical settings NSVT is a marker of increased risk for subsequent sustained tachyarrhythmia and sudden cardiac death.3 However, even today it is not known whether NSVT has a * Corresponding author. Tel.: þ30-210-641-6600; fax: þ30-210-6819779. E-mail address: [email protected] (D.G. Katritsis). cause-and-effect relationship with sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmias or is merely a surrogate marker of left ventricular dysfunction and electrical instability. Even in the case where it does hold prognostic significance, NSVT is not necessarily involved in the mechanism of death. There are certain patient groups with a high mortality due to progress of their disease. Death in these patients may be arrhythmic but this does not mean that merely preventing NSVT will unconditionally prolong life significantly. In several trials, reduction of arrhythmias or even arrhythmic death was not associated with a concomitant reduction in total mortality.4–6 The physician attending a patient presenting with an episode of NSVT has two tasks. First, to establish whether underlying occult pathology is responsible for the arrhythmia and, in the case of diagnosed heart disease, to risk-stratify the patient for appropriate management and therapy. The clinical approach to the patient with NSVT should always be considered within the particular 0195-668X/$ - see front matter c 2004 Published by Elsevier Ltd on behalf of The European Society of Cardiology. doi:10.1016/j.ehj.2004.03.022 Downloaded from http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on October 13, 2016 Received 11 December 2003; revised 5 March 2004; accepted 18 March 2004 1094 clinical context in which the arrhythmia occurs. In several settings the patient with NSVT is a clinical challenge insofar as proper management is concerned, and several questions remain unanswered. Novel data on NSVT those detected in age-matched populations without the arrhythmia.16;17 Tachycardia originating from the right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT), one of the commonest causes of NSVT in apparently healthy individuals, may cause symptoms but the risk of death is very low.18;19 Thus, recording of spontaneous NSVT in apparently healthy individuals does not imply an adverse prognosis, provided that occult cardiomyopathy and genetic arrhythmia disorders are excluded. These conditions may remain latent for several years and although apparently healthy individuals presenting with NSVT can be reassured about their prognosis, long-term follow-up is advisable. There is continually accumulating evidence for occult pathology in apparently normal subjects who develop ventricular arrhythmia.20–22 Patients with RVOT ventricular tachycardia might have subtle structural and functional abnormalities of the outflow tract as detected by magnetic resonance imaging20 and the diagnosis of RVOT ventricular tachycardia needs to be differentiated from the diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia23 and right ventricular myocarditis. The occurrence of premature ventricular depolarisation during exercise in apparently healthy subjects has not been associated with an increase in cardiovascular mortality and was considered to be a normal response to exertion.24–27 It appears now that the long-term prognostic implications of exercise-induced ventricular arrhythmias may be adverse. Recently, the Paris Prospective Study28 has confirmed earlier data29 and reported that runs of two or more consecutive ventricular depolarisations during exercise or at recovery may occur in up to 3% of healthy men and indicate an increase in cardiovascular mortality within the next 23 years by a factor of more than 2.5. This increased relative risk persisted even after adjusting for other characteristics and known predisposition to coronary artery disease. Interestingly, among subjects with a positive exercise test for ischaemia, only 3% had ectopy, whereas among subjects with exercise-induced ectopy only 6% had a positive exercise test for ischaemia. Thus, although the precise mechanism of arrhythmia is unknown in this setting and various forms of occult cardiomyopathy cannot be excluded, it does not appear to be a direct consequence of ischaemia. This study argues that exercise-induced nonsustained ventricular arrhythmia may predict coronary artery disease even in the absence of evidence of ischaemia in asymptomatic individuals. Exercise testing may also induce catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia.30;31 When recognised, this condition requires aggressive management. Clinical approach Patients with heart disease Apparently healthy individuals Initial reports indicated that the presence of complex ventricular ectopy and NSVT increase the risk of subsequently observed heart disease.14;15 However, when the presence of occult ischaemia or structural heart disease was excluded, NSVT was not found to adversely influence prognosis, with cardiac event rates not exceeding Ischaemic heart disease The occurrence of NSVT during the first day of acute myocardial infarction, although frequent (40% to 70% of patients), is not associated with increased risk for subsequent long-term mortality.32 Following the first 24 h postinfarction, NSVT is detected in approximately 5–10% of the patients, particularly during the first months, and Downloaded from http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on October 13, 2016 Reliable epidemiologic data on NSVT are difficult to obtain. Most of the available information comes from older studies based on Holter monitoring. Usually, although not invariably, patients remain asymptomatic; the reproducibility of NSVT recordings is documented in only half of the patients with this arrhythmia.7 The advent of implantable permanent pacemakers and implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD) with extensive ECG monitoring capabilities has made it possible to compile considerable information from patients with heart disease. There is emerging evidence from ICD data that NSVT is a distinct tachyarrhythmia that may cause syncope without causing death in patients with heart disease, and that the incidence of polymorphic NSVT relative to sustained arrhythmia is greater than previously believed.8 Reports from the Analysis of the Multicenter UnSustained Tachycardia Trial (MUSTT)9 substudies have provided valuable information regarding the prevalence and prognostic significance of NSVT in the context of different clinical settings. It seems that not only the frequency of NSVT but the circumstances under which it occurs are important. MUSTT data have shown prognostic differences in patients with in-hospital, as opposed to out-of-hospital, identified NSVT.10 Overall mortality rates at two and five years of follow-up were 24% and 48%, respectively, for inpatients and 18% and 38% for outpatients (adjusted p ¼ :018). In patients undergoing surgical coronary revascularisation, the occurrence of NSVT within the early (first 10 days) postrevascularisation period portends a far better outcome than when it occurs later after CABG (10–30 days) or in nonpostoperative settings.11 Indeed, the approximate 2-year mortality rates for patients with early postrevascularisation NSVT, late postrevascularisation NSVT, and nonpostoperative NSVT were 14%, 23%, and 24%, respectively.11 However, when sustained ventricular tachycardia is inducible in patients with early postoperative NSVT, the outcome is worse than in noninducible patients.12 In the MUSTT, racial differences have also been shown to influence the outcome of patients with NSVT and reduced left ventricular function.13 D.G. Katritsis, A.J. Camm Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia: where do we stand? heart failure survival trial of antiarrhythmic therapy (CHF-STAT) despite the elimination of ventricular ectopy.46 Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia can be detected in approximately 5% of ischaemic patients with preserved left ventricular function, apparently excluding previous myocardial infarction, but does not appear to indicate an adverse clinical outcome.47;48 However, NSVT appears now to occur in the majority of ischaemic patients with reduced left ventricular function,49;50 Induction of sustained arrhythmia by programmed electrical stimulation51;52 still appears to retain predictive power in ischaemic patients with impaired left ventricular function (LVEF<40%).50 Recently, the MUSTT investigators analysed the relation of ejection fraction and inducible ventricular tachyarrhythmias to mode of death in 1791 patients enrolled in MUSTT who had not already received antiarrhythmic therapy. Total and arrhythmic mortality were higher in patients with an ejection fraction <30% than in those whose ejection fractions were 30% to 40%. Inducibility of tachyarrhythmia identified patients for whom death was significantly more likely to be arrhythmic. This study therefore suggested that the major utility of electrophysiologic testing may be restricted to patients having an ejection fraction between 30% and 40%.50 In ischaemic patients with relatively well preserved left ventricular function (LVEF[40%), the role of programmed electrical stimulation is not established. There are cases, however, where programmed electrical stimulation tests may reveal monomorphic ventricular tachycardia in the postinfarction patient. Noninducible patients may not have a lower risk for arrhythmic events. Both the MUSTT9 and the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial (MADIT) II53 have suggested that patients noninducible by electrophysiologic testing have a risk for sudden cardiac death similar to that of inducible patients. In the MUSTT, the inducible group had a 2-year total mortality rate of 28%, whereas the noninducible group had 21%. The mortality rate in noninducible patients is high enough to question the need for programmed electrical stimulation. Actually, data from MADIT II suggest an even higher rate of appropriate ICD shocks in patients who were noninducible at electrophysiologic testing.53 These findings are consistent with analyses of stored ICD data, which have clearly shown that there was little association between spontaneous and induced ventricular arrhythmias.54 Thus, electrophysiology testing cannot select patients with a favourable outcome. The value of signal-averaged ECG and autonomic markers, such as heart rate variability and depressed baroreflex sensitivity, for determining prognosis and selecting high-risk patients with NSVT is not established.3;40 Analysis of ATRAMI patients has shown that NSVT, heart rate variability, and depressed baroreflex sensitivity were all significantly and independently associated with increased mortality. Depressed baroreflex sensitivity, in particular, identified a subgroup with the same mortality risk as patients with NSVT and reduced LVEF.40 Recently, the Multiple Risk Factor Analysis Trial (MRFAT) showed that in the beta-blocking era the common arrhythmia risk Downloaded from http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on October 13, 2016 has been considered to have adverse prognostic significance.33–35 Previous studies have emphasised the importance of NSVT as an important prognostic determinant for arrhythmic death, even independent of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).36;37 It now appears that in the patient with ischaemic heart disease, NSVT no longer appears to be an independent predictor of death if other factors such as the ejection fraction are taken into account. In the Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto Miocardico-2 (GISSI-2, Italian Group for the Study of Survival after Myocardial Infarction-2) trial, NSVT was a significant predictor of mortality in univariate analysis, but not independently in multivariate analysis involving other clinical variables.35 Similarly, in the electrophysiologic study versus electrocardiographic monitoring (ESVEM) trial, although univariate analysis suggested that there was an association between the presenting arrhythmia and outcome, multivariate analysis failed to establish the predictive value of the presenting arrhythmia.38 Left ventricular ejection fraction was the single most important predictor of arrhythmic death or cardiac arrest in patients with lifethreatening arrhythmias who were treated with antiarrhythmic drugs. Over a 6-year follow-up period, 285 of the 486 patients enrolled in the ESVEM trial had an arrhythmia recurrence. Patients with LVEF>40% had a 5% risk of developing a malignant arrhythmia, whereas for each decrease of 5% in LVEF, the risk of cardiac arrest or arrhythmic death increased by 15%.38 In another study in which most patients (78%) had revascularisation of the infarct-related artery, NSVT early after myocardial infarction (4–16 days) had a low prevalence (9%) and carried a significant but low relative risk for the composite endpoint of cardiac death, ventricular tachycardia, or ventricular fibrillation, but not for arrhythmic events considered alone.39 Interestingly, in a recent analysis of 1071 ATRAMI patients, many of which underwent thrombolysis (63%), NSVT (with a prevalence of 13.4%) was found to adversely influence prognosis, independent of reduced LVEF.40 Although Holter monitoring is a valuable diagnostic tool in detecting patients with NSVT, its usefulness for the subsequent follow-up and evaluation of treatment is questionable. First, the prognostic significance of the frequency of NSVT runs or other ECG variables such as heart rate and complex ventricular ectopy is unknown. Recent trials in postinfarction patients have yielded conflicting evidence with regards to the relationship between the frequency of ventricular ectopy and heart rate with cardiac mortality.41;42 It seems that in the betablocking era, all common arrhythmia risk variables, including NSVT, have diminished predictive power in identifying postinfarction patients at risk of sudden cardiac death.43 Second, the suppression of frequent ventricular ectopy or NSVT runs following beta-blockade or amiodarone therapy does not imply a favourable diagnosis. Mortality was increased in the cardiac arrhythmia suppression trials (CAST and CAST II), despite reduced ectopic activity,44;45 whereas mortality was not reduced by amiodarone in the Veterans administration congestive 1095 1096 Nonischaemic heart disease In conditions other than ischaemic heart disease the independent prognostic significance of NSVT, at least as far as sudden arrhythmic death is concerned, is even less established. There has been some evidence regarding its prognostic significance in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the young,56;57 but several questions remain in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy46;58–60 and other congenital or idiopathic arrhythmogenic conditions.61–64 Clearly, more data are needed for risk stratification of these patients and ongoing trials are eagerly awaited in this respect.65;66 The high prevalence of ventricular arrhythmias on Holter monitoring in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy (up to 80%)46;58;60;67;68 makes their prognostic significance difficult to assess and the prognostic value of NSVT in this setting is questionable. The GESICA trial has provided evidence that in patients with NSVT the risk of sudden death compared to nonsudden death was significantly increased;59;60 this was not confirmed in the CHFSTAT.46 Furthermore, although amiodarone therapy was associated with decreased mortality in the GESICA trial, no such effect was observed in the CHF-STAT trial, despite the higher prevalence of NSVT in this cohort.60;46 No advantage of ICD implantation over amiodarone was shown in the AMIOVIRT trial in patients with LVEF<35% and NSVT,69 despite suggestions that NSVT patients may require an ICD as badly as patients with a history of previous ventricular fibrillation.70 Similarly, disappointing results with the use of ICDs for primary prevention in patients with nonischaemic cardiomyopathy (LVEF<30%) have been recently reported by the CAT investigators.71 The Marburg Cardiomyopathy Study72 has recently reported on noninvasive arrhythmia risk stratification in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Although NSVT and frequent ventricular premature beats showed a significant association with a higher arrhythmia risk on univariate analysis, on multivariate analysis only LVEF was found to be a significant predictor of major arrhythmic events with a relative risk of 2.3 per 10% decrease of LVEF. Signal-averaged ECG, baroreflex sensitivity, heart rate variability, and T-wave alternans were not helpful for arrhythmia risk stratification. Results of subanalyses from the still ongoing DEFINITE and SCD-HeFT trials should also provide data on the prognostic value of NSVT in this setting. In hypertrophic cardiomyopathy 20–30% of patients may have NSVT, whereas in patients with a history of cardiac arrest this proportion approaches 80%.56;73;74 It has been suggested that NSVT only has prognostic importance in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy when it is repetitive, prolonged, or associated with symptoms.3 In a recent study on 531 patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, no relation between the Table 1 Clinical significance of NSVT Clinical setting Apparently normal heart Random finding During or postexercise Ischemic heart disease Acute MI < 24 h Acute MI > 24 h Chronic IHD with LVEF > 40% Chronic IHD with LVEF < 40% Significance No adverse prognostic significance in the absence of occult pathology May predict IHD and increased cardiac mortality No adverse prognostic significance Adverse prognostic significance Prognostic significance unknown Adverse prognostic significance DCM Independent prognostic significance not established, as opposed to LVEF HOCM Probable adverse prognostic significance, especially in the young Primary VF, congenital long-QT, Brugada syndrome, ARVD, repaired congenital abnormalities, valvular disease, hypertension Prognostic significance unknown IHD: ischaemic heart disease, MI: myocardial infarction, LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction, DCM: dilated cardiomyopathy, HOCM: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, VF: ventricular fibrillation, ARVD: arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. Downloaded from http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on October 13, 2016 variables, particularly autonomic and standard ECG markers, have limited predictive power in identifying patients at risk of sudden cardiac death.43 In a 43 ± 15month follow-up of 675 patients, sudden cardiac death was weakly predicted only by reduced LVEF (<40%), NSVT, and abnormal signal-averaged ECG, but not by autonomic markers or ECG variables. The positive predictive accuracy of these markers (low LVEF, NSVT, and abnormal signal-averaged ECG), however, was low, 8%, 12%, and 13%, respectively.43 More data are clearly needed to establish the clinical utility of autonomic markers, particularly in the setting of NSVT. Based on the MUSTT and MADIT results, patients with LVEF below 40% and NSVT should undergo electrophysiologic testing with a view to ICD implantation. Guided antiarrhythmic drug therapy no longer has a role in the treatment of these patients.55 Patients with LVEF less than 30% should be considered high-risk for arrhythmic death, regardless of the presence of NSVT, according to MADIT II. So far, no hard data exist to guide the management of ischaemic patients with NSVT and LVEF>40%. D.G. Katritsis, A.J. Camm Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia: where do we stand? Conclusions Based on the evidence presented as well as on our own experience, we can make the following statements (Table 1). In the documented absence of heart disease, spontaneous NSVT does not appear to carry any adverse prognostic significance. Exercise-induced or postexercise NSVT may predict the future development of coronary artery disease and increased cardiac mortality. In ischaemic patients with LVEF<40%, NSVT has an adverse prognostic significance and electrophysiologic testing with a view to ICD implantation is indicated. In patients with LVEF>40%, the independent prognostic significance of NSVT is unknown and the role of electrophysiologic testing not established, although we do advocate its use in this setting. The independent prognostic value of NSVT in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy has never been proven. NSVT in patients with hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy probably carries an adverse prognostic significance, particularly in the young. The prognostic value of NSVT in conditions such as the long-QT syndromes, primary ventricular fibrillation, and Brugada syndrome, as well as in patients with hypertension and valvular disease, is not established. Thus, the clinical approach to the patient with NSVT should always be considered within the particular clinical context in which the arrhythmia occurs. References 1. Buxton AE, Duc J, Berger EE et al. Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia. Cardiol Clin 2000;18:327–36. 2. Kinder C, Tamburro P, Kopp D et al. Thee clinical significance of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia: current perspectives. PACE 1994;17:637–64. 3. Camm AJ, Katritsis D. Risk stratification of patients with ventricular arrhythmias. In: Zipes DP, Jalife J, editors. Clinical electrophysiology From cell to bedside. 3rd ed. Saunders; 2000. p. 808–27. 4. Elizari MV, Martinez JM, Belziti C et al. Mortality following early administration of amiodarone in acute myocardial infarction: results of the GEMICA trial. Circulation 1996;94(suppl 1):90. 5. Cairns JA, Connolly SJ, Gent M et al. Post-myocardial infarction mortality in patients with ventricular premature depolarizations. Circulation 1991;84:550–7. 6. Julian DG, Camm AJ, Frangin J et al. Randomised trial of effect of amiodarone on mortality in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after recent myocardial infarction: EMIAT. Lancet 1997;349: 662–3. 7. Senges JC, Becker R, Schreiner KD et al. Variability of Holter electrocardiographic findings in patients fulfilling the noninvasive MADIT criteria. Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2002;25:183–90. 8. Farmer DM, Swygman CA, Wang PJ et al. Evidence that nonsustained polymorphic ventricular tachycardia causes syncope (data from implantable cardioverter defibrillators). Am J Cardiol 2003;91:606–9. 9. Buxton AE, Lee KL, Fisher JD et al. A randomized study of the prevention of sudden death in patients with coronary artery disease. Multicenter Unsustained Tachycardia Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med 1999;341:1882–90. 10. Pires LA, Lehmann MH, Buxton AE et al. The Multicenter Unsustained Tachycardia Trial Investigators. Differences in inducibility and prognosis of in-hospital versus out-of-hospital identified nonsustained ventricular tachycardia in patients with coronary artery disease: clinical and trial design implications. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38:1156–62. 11. Pires LA, Hafley GE, Lee KL et al. Multicenter Unsustained Tachycardia Trial Investigators. Prognostic significance of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia after coronary bypass surgery in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2002;13:757–63. 12. Mittal S, Lomnitz DJ, Mirchandani S et al. Prognostic significance of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia after revascularization. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2002;13:342–6. 13. Russo AM, Hafley GE, Lee KL et al. Multicenter Unsustained Tachycardia Trial Investigators. Racial differences in outcome in the Multicenter UnSustained Tachycardia Trial (MUSTT): a comparison of whites versus blacks. Circulation 2003;108: 67–72. 14. Cullen K, Stenhouse NS, Wearne KL et al. Electrocardiograms and 13 year cardiovascular mortality in Busselton study. Br Heart J 1982;47:209–12. 15. Bikkina M, Larson MG, Levy D. Prognostic implications of asymptomatic ventricular arrhythmias: the Framingham heart study. Ann Int Med 1992;117:990–6. 16. Kennedy HL, Whitlock JA, Sprague MK et al. Long-term follow-up of asymptomatic healthy subjects with frequent and complex ventricular ectopy. N Engl J Med 1985;312:193–8. 17. Montague TJ, McPherson DD, MacKenzie BR et al. Frequent ventricular ectopic activity without underlying cardiac disease: Analysis of 45 subjects. Am J Cardiol 1983;52:980–4. 18. Ritchie AH, Kerr CR, Qi A et al. Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia arising from the right ventricular outflow tract. Am J Cardiol 1989;64:594–8. 19. Katritsis D, Gill J, Camm AJ. Repetitive monomorphic ventricular tachycardia. In: Zipes DP, Jalife J, editors. Clinical electrophysiology From cell to bedside. Saunders; 1995. p. 900–6. 20. Carlson MD, White RD, Trohman RG et al. Right ventricular outflow tract ventricular tachycardia: detection of previously unrecognized anatomic abnormalities using cine magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol 1994;24:720–7. Downloaded from http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on October 13, 2016 frequency, duration, or rate of NSVT episodes could be demonstrated.57 However, NSVT was associated with a substantial increase in sudden death risk in young patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.57 The presence of high-risk factors, including NSVT in the young, may justify defibrillator implantation as primary prevention in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.75 In cases of primary ventricular fibrillation, congenital long QT, and Brugada syndrome, the detection of NSVT on Holter or exercise testing has no predictive value to guide appropriate therapy, although ICD implantation is recommended, at least in symptomatic patients.61;63;76 In patients with valvular disease the incidence of NSVT is considerable (up to 25% in aortic stenosis and in significant mitral regurgitation) and appears to be a marker of underlying left ventricular pathology.77;78 Up to 65% of patients with surgical repair of tetralogy of Fallot have ventricular ectopy, whereas NSVT occurs in up to 17% of patients either at rest or during exercise.79;80 In patients with arterial hypertension, NSVT is correlated to the degree of cardiac hypertrophy and subendocardial fibrosis.81;82 Approximately 15% of patients with hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy present NSVT, as opposed to 6% of patients with hypertension alone.81–83 No convincing evidence exists to prove that NSVT is an independent predictor of sudden death in patients with valve disease, repaired congenital abnormalities, or hypertension. In these conditions, therefore, the approach to the patient from the point of view of arrhythmias currently remains empirical. 1097 1098 42. Abildstrom SZ, Jensen BT, Agner E, et al. BEAT Study Group. Heart rate versus heart rate variability in risk prediction after myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2003;14:168–173. 43. Huikuri HV, Tapanainen JM, Lindgren K et al. Prediction of sudden cardiac death after myocardial infarction in the beta-blocking era. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:652–8. 44. Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST) Investigators. Preliminary report: effect of encainide and flecainide on mortality in a randomized trial of arrhythmia suppression after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1989;321:406–412. 45. The Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial-II Investigators. Effect of antiarrhythmic agent moricizine on survival after myocardial infarction. The Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial-II. N Engl J Med 1992;327:227–233. 46. Singh SN, Fletcher RD, Fisher SG et al. Amiodarone in patients with congestive heart failure and asymptomatic ventricular arrhythmia. Survival Trial of Antiarrhythmic Therapy in Congestive Heart Failure. N Engl J Med 1995;333:77–82. 47. Ruberman W, Weinblatt E, Golberg JD et al. Ventricular premature beats and mortality after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1977;297:750–7. 48. Califf RM, McKinnis RA, Burks J et al. Prognostic implications of ventricular arrhythmias during 24 hour ambulatory monitoring in patients undergoing cardiac catheterization for coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 1982;50:23–31. 49. Moss AJ. Dead is dead, but can we identify patients at increased risk for sudden cardiac death? J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:659–60. 50. Buxton AE, Lee KL, Hafley GE, et al. MUSTT Investigators. Relation of ejection fraction and inducible ventricular tachycardia to mode of death in patients with coronary artery disease: an analysis of patients enrolled in the multicenter unsustained tachycardia trial. Circulation 2002;106:2466–2472. 51. Kowey PR, Taylor JE, Marinchak RA et al. Does programmed stimulation really help in the evaluation of patients with nonsustained ventricular tachycardia? Results of a meta-analysis. Am Heart J 1992;123:481–5. 52. Wilber DJ, Olshansky B, Moran JF et al. Electrophysiological testing and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia. Use and limitations in patients with coronary artery disease and impaired ventricular function. Circulation 1990;82:350–8. 53. Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ et al. Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II Investigators. Prophylactic use of an implanted defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2002;346:877–83. 54. Monahan KM, Hadjis T, Hallett N et al. Relation of induced to spontaneous ventricular tachycardia from analysis of stored far-field implantable defibrillator electrograms. Am J Cardiol 1999;83: 349–53. 55. Wyse DG, Talajic M, Hafley GE et al. Antiarrhythmic drug therapy in the Multicenter UnSustained Tachycardia Trial (MUSTT): drug testing and as-treated analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38:344–51. 56. Maron BJ, Savage DD, Wolfson JK et al. Prognostic significance of 24 hour ambulatory ECG monitoring in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a prospective study. Am J Cardiol 1981;48: 252–7. 57. Monserrat L, Elliott PM, Gimeno JR et al. Non-sustained ventricular tachycardia in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: an independent marker of sudden death risk in young patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:873–9. 58. Tamburro P, Wilber D. Sudden death in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am Heart J 1992;124:1035–45. 59. Doval H, Nul D, Grancelli H et al. Randomised trial of low-dose amiodarone in severe congestive heart failure. Lancet 1994;1: 493–8. 60. Doval HC, Nul DR, Grancelli HO et al. Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia in severe heart failure. Independent marker of increased mortality due to sudden death. GESICA-GEMA Investigators. Circulation 1996;94:3198–203. 61. Antzelevitch C, Brugada P, Brugada J et al. Brugada syndrome: 1992–2002: a historical perspective. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:1665–71. 62. Priori SG, Napolitano C, Gasparini M et al. Natural history of Brugada syndrome: insights for risk stratification and management. Circulation 2002;105:1342–7. Downloaded from http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on October 13, 2016 21. Chimenti C, Calabrese F, Thiene G et al. Inflammatory left ventricular microaneurysms as a cause of apparently idiopathic ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Circulation 2001;104:168–73. 22. Ouyang F, Cappato R, Ernst S et al. Electroanatomic substrate of idiopathic left ventricular tachycardia: unidirectional block and macroreentry within the Purkinje network. Circulation 2002;105:462–9. 23. O’Donnell D, Cox D, Bourke J et al. Clinical and electrophysiological differences between patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia and right ventricular outflow tract tachycardia. Eur Heart J 2003;24:801–10. 24. Fleg J, Lakatta E. Prevalence and prognosis of exercise-induced nonsustained ventricular tachycardia in apparently healthy volunteers. Am J Cardiol 1984;54:762–4. 25. Bruce RA, DeRouen TA, Hossack KF. Value of maximal exercise tests in risk assessment of primary coronary heart disease events in healthy men. Five years’ experience of the Seattle heart watch study. Am J Cardiol 1980;46(3):371–8. 26. Drory Y, Pines A, Fisman EZ et al. Persistence of arrhythmia exercise response in healthy young men. Am J Cardiol 1990;66(15):1092–4. 27. Nair CK, Aronow WS, Sketch MH et al. Diagnostic and prognostic significance of exercise-induced premature ventricular complexes in men and women: a four year follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol 1983;1:1201–6. 28. Jouven X, Zureik M, Desnos M et al. Long-term outcome in asymptomatic men with exercise-induced premature ventricular depolarizations. N Engl J Med 2000;343:826–33. 29. Udall JA, Ellestad MH. Predictive implications of ventricular premature contractions associated with treadmill stress testing. Circulation 1977;56(6):985–9. 30. Vlay SC. Catecholamine-sensitive ventricular tachycardia. Am Heart J 1987;114:455–61. 31. Leenhardt A, Lucet V, Denjoy I et al. Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia in children. A 7-year follow-up of 21 patients. Circulation 1995;91:1512–9. 32. Cheema AN, Sheu K, Parker M et al. Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia in the setting of acute myocardial infarction: tachycardia characteristics and their prognostic implications. Circulation 1998;98:2030–6. 33. Bigger JT, Fleiss JL, Rolnitzky LM. Prevalence, characteristics and significance of ventricular tachycardia detected by 24-hour continuous electrocardiographic recordings in the late hospital phase of acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 1986;58:1151–60. 34. Burkart F, Pfisterer M, Kiowski W et al. Effect of antiarrhythmic therapy on mortality in survivors of myocardial infarction with asymptomatic complex ventricular arrhythmias: Basel Antiarrhythmic Study of Infarct Survival (BASIS). J Am Coll Cardiol 1990;16:1711–8. 35. Maggioni AP, Zuanetti G, Franzosi MG, et al, on behalf of GISSI-2 Investigators. Prevalence and prognostic significance of ventricular arrhythmias after acute myocardial infarction in the fibrinolytic era: GISSI results. Circulation 1993;87:312–322. 36. The Multicenter Post-infarction Research Group. Risk stratification and survival after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1983;309:331–336. 37. Mukharji J, Rude RE, Poole WK et al. Risk factors for sudden death after acute myocardial infarction: Two-year follow-up. Am J Cardiol 1984;54:31–6. 38. Caruso AC, Marcus FI, Hahn EA et al. Predictors of arrhythmic death and cardiac arrest in the ESVEM trial. Electrophysiologic study versus electromagnetic monitoring. Circulation 1997;96:1888–92. 39. Hohnloser SH, Klingenheben T, Zabel M et al. Prevalence, characteristics and prognostic value during long-term follow-up of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia after myocardial infarction in the thrombolytic era. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;33:1895–902. 40. La Rovere MT, Pinna GD, Hohnloser SH, et al. ATRAMI Investigators. Autonomic tone and reflexes after myocardial infarction. Baroreflex sensitivity and heart rate variability in the identification of patients at risk for life-threatening arrhythmias: implications for clinical trials. Circulation 2001;103:2072–2077. 41. La Rovere MT, Bigger Jr JT, Marcus FI et al. Baroreflex sensitivity and heart-rate variability in prediction of total cardiac mortality after myocardial infarction. ATRAMI (Autonomic Tone and Reflexes After Myocardial Infarction) Investigators. Lancet 1998;351:478–84. D.G. Katritsis, A.J. Camm Nonsustained ventricular tachycardia: where do we stand? 73. McKenna WJ, Behr ER. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: management, risk stratification, and prevention of sudden death. Heart 2002;87:169–76. 74. Maron BJ. Ventricular arrhythmias, sudden death, and prevention in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Curr Cardiol Rep 2000;2:522–8. 75. Maron BJ, Shen WK, Link MS et al. Efficacy of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators for the prevention of sudden death in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2000;342:365–73. 76. Brugada J, Brugada R, Antzelevitch C et al. Long-term follow-up of individuals with the electrocardiographic pattern of right bundlebranch block and ST-segment elevation in precordial leads V(1) to V(3). Circulation 2002;105:73–8. 77. Klein RC. Ventricular arrhythmias in aortic valve disease: analysis of 102 patients. Am J Cardiol 1984;53:1079–83. 78. Martinez-Rubio A, Schwammenthal Y, Schwammenthal E et al. Patients with valvular heart disease presenting with sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmias and syncope. Results of programmed ventricular stimulation and long-term follow-up. Circulation 1997;96:500–8. 79. Garson A, Gilette PC, Gutgesell HP. Stress-induced ventricular arrhythmias after tetralogy of Fallot repair. Am J Cardiol 1980;46:1006. 80. Deanfield JE, McKenna WJ, Hallidie-Smith KA. Detection of late arrhythmias and conduction disturbance after correction of tetralogy of Fallot. Br Heart J 1980;44:248. 81. Cameron JS, Myerburg RJ, Wong SS et al. Electrophysiological consequences of chronic experimentally induced left ventricular pressure overload. J Am Coll Cardiol 1983;2:481–7. 82. McLenaghan JM, Henderson E, Morris KI et al. Ventricular arrhythmias in patients with hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy. N Engl J Med 1987;317:787–92. 83. Papademetriou V, Price M, Notargiacomo A et al. Effect of diuretic therapy on ventricular arrhythmias in hypertensive patients with and without left ventricular hypertrophy. Am Heart J 1985;110:595–9. Downloaded from http://eurheartj.oxfordjournals.org/ by guest on October 13, 2016 63. Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ et al. Effectiveness and limitations of beta-blocker therapy in congenital LQTS. Circulation 2000;101: 616–23. 64. Katritsis D, Camm AJ. Role of invasive electrophysiology testing in the evaluation and management of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation. Cardiac EP Review 1998;1:452–6. 65. Klein H, Auricchio A, Reek S et al. New primary prevention trials of sudden cardiac death in patients with left ventricular dysfunction: SCD-HEFT and MADIT-II. Am J Cardiol 1999;83(5B):91D–7D. 66. Kadish A, Quigg R, Schaechter A et al. Defibrillators in nonischemic cardiomyopathy treatment evaluation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2000;23:338–43. 67. Singh SN, Fisher SG, Carson PE et al. Prevalence and significance of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia in patients with premature ventricular contractions and heart failure treated with vasodilator therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;32:942–7. 68. Sugrue DD, Rodeheffer RJ, Codd MB et al. The clinical course of idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. A population-based study. Ann Intern Med 1992;117:117–23. 69. Strickberger SA, Hummel JD, Bartlett TG, et al. AMIOVIRT Investigators. Amiodarone versus implantable cardioverter-defibrillator: randomized trial in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy and asymptomatic nonsustained ventricular tachycardia–AMIOAMIOVIRT. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:1707–1712. 70. Grimm W, Hoffmann JJ, Muller HH et al. Implantable defibrillator event rates in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia on Holter and a left ventricular ejection fraction below 30%. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39: 780–7. 71. Bansch D, Antz M, Boczor S et al. Primary prevention of sudden cardiac death in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: the Cardiomyopathy Trial (CAT). Circulation 2002;105:1453–8. 72. Grimm W, Christ M, Bach J et al. Noninvasive arrhythmia risk stratification in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: results of the Marburg Cardiomyopathy Study. Circulation 2003;108:2883–91. 1099