* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Essence of Zen.vp

Buddhist cosmology of the Theravada school wikipedia , lookup

Persecution of Buddhists wikipedia , lookup

Mind monkey wikipedia , lookup

Buddhist influences on print technology wikipedia , lookup

Tara (Buddhism) wikipedia , lookup

Buddhist art wikipedia , lookup

Pratītyasamutpāda wikipedia , lookup

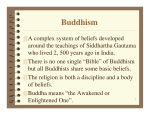

Gautama Buddha wikipedia , lookup

Nirvana (Buddhism) wikipedia , lookup

Early Buddhist schools wikipedia , lookup

Triratna Buddhist Community wikipedia , lookup

Greco-Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

History of Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

Buddhist ethics wikipedia , lookup

Buddhist texts wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism and sexual orientation wikipedia , lookup

Sanghyang Adi Buddha wikipedia , lookup

Decline of Buddhism in the Indian subcontinent wikipedia , lookup

D. T. Suzuki wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism and Hinduism wikipedia , lookup

Buddhist meditation wikipedia , lookup

Buddhist philosophy wikipedia , lookup

Dhyāna in Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism in Myanmar wikipedia , lookup

Silk Road transmission of Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism in Vietnam wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism in Japan wikipedia , lookup

Buddha-nature wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism in the United States wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism and psychology wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism and Western philosophy wikipedia , lookup

Pre-sectarian Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

Women in Buddhism wikipedia , lookup