* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Synthetic cannabinoid JWH-018 and psychosis

Survey

Document related concepts

Drug design wikipedia , lookup

Neuropsychopharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Cannabinoid receptor antagonist wikipedia , lookup

Drug interaction wikipedia , lookup

Pharmaceutical industry wikipedia , lookup

Pharmacokinetics wikipedia , lookup

Drug discovery wikipedia , lookup

Prescription costs wikipedia , lookup

Pharmacogenomics wikipedia , lookup

Theralizumab wikipedia , lookup

Pharmacognosy wikipedia , lookup

Neuropharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Medical cannabis wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

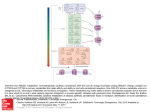

G Model DAD-4024; No. of Pages 6 ARTICLE IN PRESS Drug and Alcohol Dependence xxx (2011) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Drug and Alcohol Dependence journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/drugalcdep Full length article Synthetic cannabinoid JWH-018 and psychosis: An explorative study Susanna Every-Palmer ∗ Te Korowai-Whāriki, A Capital and Coast District Health Board Service, Ratonga Rua O Porirua, Regional Forensic Service, Raiha Street, P O Box 50-233 Porirua, New Zealand a r t i c l e i n f o Article history: Received 7 July 2010 Received in revised form 6 January 2011 Accepted 15 January 2011 Available online xxx Keywords: Cannabinoids Psychoses, substance-induced Designer drugs Qualitative research Psychotic disorders Forensic psychiatry Spice JWH-018 a b s t r a c t Background: Aroma, Spice, K2 and Dream are examples of a class of new and increasingly popular recreational drugs. Ostensibly branded “herbal incense”, they have been intentionally adulterated with synthetic cannabinoids such as JWH-018 in order to confer on them cannabimimetic psychoactive properties while circumventing drug legislation. JWH-018 is a potent cannabinoid receptor agonist. Little is known about its pharmacology and toxicology in humans. This is the first research considering the effects of JWH-018 on a psychiatric population and exploring the relationship between JWH-018 and psychotic symptoms. Method: This paper presents the results of semi-structured interviews regarding the use and effects of JWH-018 in 15 patients with serious mental illness in a New Zealand forensic and rehabilitative service. Results: All 15 subjects were familiar with a locally available JWH-018 containing product called “Aroma” and 86% reported having used it. They credited the product’s potent psychoactivity, legality, ready availability and non-detection in drug testing as reasons for its popularity, with most reporting it had replaced cannabis as their drug of choice. Most patients had assumed the product was “natural” and “safe”. Anxiety and psychotic symptoms were common after use, with 69% of users experiencing or exhibiting symptoms consistent with psychotic relapse after smoking JWH-018. Although psychological side effects were common, no one reported becoming physically unwell after using JWH-018. Three subjects described developing some tolerance to the product, but no one reported withdrawal symptoms. Conclusion: It seems likely that JWH-018 can precipitate psychosis in vulnerable individuals. People with risk factors for psychosis should be counseled against using synthetic cannabinoids. © 2011 Published by Elsevier Ireland Ltd. 1. Introduction While cannabis use has a long history, the emergence of synthetic cannabinoids such as JWH-018 is recent. This article explores the relationship between JWH-018 and psychotic symptoms and reports 15 forensic inpatients’ experiences with synthetic cannabinoid containing products (SCCPs). 1.1. Background: SCCPs emerge as a new drug trend Spice, Aroma, K2 and Dream are examples of a large and evolving group of smokable products branded as ‘herbal incense’, but found by users to have potent cannabis-like properties. Spice first started appearing on internet sites and in specialized shops around 2004 (Dresen et al., 2010). Warning messages on the product stating it was not intended for human consumption contrasted with sophisticated packaging ∗ Tel.: +64 4 385 5999; fax: +64 4 918 2477. E-mail addresses: Susanna [email protected], [email protected] and marketing, promoting the product as a cannabis alternative which was undetectable by conventional drug testing methodology. It was not until December 2008 that researchers reported the reason for Spice’s cannabis-like properties: Spice had been ‘laced’ with undeclared synthetic cannabinoids JWH-018 and CP 47,497 (Auwärter et al., 2009). It is believed that these synthetic cannabinoids were dissolved in a solvent which was then sprayed on a plant-derived base for delivery (Vardakou et al., 2010). The herbal ingredients cited on Spice’s packaging did not appear to contribute to its psychoactivity; in fact they were not even present in most of the samples tested (Piggee, 2009). Since being identified in “herbal” products JWH-018 and CP 47,497 and have been banned in a number of European countries and some American States (Vardakou et al., 2010). Three weeks after CP-compounds and JWH-018 were banned in Germany, second generation products (e.g., analogues such as JWH-073) appeared on the market, suggesting the manufacturers had anticipated prohibition and had already synthesized an array of alternatives (Lindigkeit et al., 2009). Currently “headshops” and the internet offer an ever-expanding array of synthetic cannabinoids originating from 3 chemically distinct groups 0376-8716/$ – see front matter © 2011 Published by Elsevier Ireland Ltd. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.01.012 Please cite this article in press as: Every-Palmer, S., Synthetic cannabinoid JWH-018 and psychosis: An explorative study. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2011), doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.01.012 G Model DAD-4024; No. of Pages 6 ARTICLE IN PRESS 2 S. Every-Palmer / Drug and Alcohol Dependence xxx (2011) xxx–xxx (JWH-, CP- and HU-compounds), alongside oleamide, a fatty acid with cannabinoid-like activity (EMCDDA, 2009; Hudson et al., 2010; Lindigkeit et al., 2009; Uchiyama et al., 2009; United States Drug Enforcement Administration, 2009). The rapid proliferation of synthetic cannabinoid products over the last 4 years has been labeled the “Spice phenomenon” (EMCDDA, 2009). Griffiths et al. (2010) consider the Spice phenomenon to be a “case study” of how existing models of drug control and response are being challenged by globalization, internet technology and innovation in the drug market. 1.2. Synthetic cannabinoids and psychosis Little data is available on the psychological and other risks of synthetic cannabinoids. Psychotic relapses following the use of a JWH-018 product in 5 patients in our forensic service have already been reported (EveryPalmer, 2010). There is one published case report of tolerance and withdrawal phenomena in the literature (Zimmermann et al., 2009) and another of drug induced psychosis (Müller et al., 2010). Both these cases were attributed to Spice, which at the time contained JWH-018 and CP 47,497. There is also an increasing number of reports describing patients presenting for emergency medical care after using “Spice” products. Common features of many of these presentations have included anxiety symptoms, agitation, tachycardia, paranoia and hallucinations (Banerji et al., 2010; Bebarta et al., 2010; Piggee, 2009; Vearrier and Osterhoudt, 2010). Inter-batch variation in the type and quantity of cannabinoids present has also resulted in accidental overdosing requiring hospitalization (Auwärter et al., 2009). A number of self-reports of users experiencing anxiety and psychotic symptoms following the use of JWH-018 and other cannabinoids can be found on the internet (e.g., http://www. erowid.org/experiences/subs/exp JWH018.shtml#Train Wrecks & Trip Disasters). 1.3. Synthetic cannabinoid use in New Zealand JWH compounds (e.g., JWH-018, JWH-015 and JWH-073) are currently unregulated in New Zealand and are widely available in ‘headshops’ and over the internet. New Zealand may be a particularly opportune market for cannabimimetic drugs with an annual prevalence of cannabis use at 14.6%, one of the highest in the world (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2010). Cannabis use is particularly prevalent in criminal populations with 55% of New Zealand prison inmates qualifying for lifetime diagnoses of cannabis abuse or dependence (New Zealand Department of Corrections, 1999). In forensic psychiatric services, substance use is prohibited, and abstinence is monitored by urine drug screens. However, the arrival of unregulated synthetic cannabinoids into the market is posing new challenges to forensic and other mental health services. 2. Methodology 2.1. The sample Subjects were recruited from a Regional Forensic and Rehabilitation service. Inclusion criteria were patients between the ages of 18 and 65 who were able to give informed consent and were residing in a low security forensic inpatient unit, or waiting placement in such a setting. Clients who were considered high risk of assault or too unwell to be interviewed alone were excluded for safety reasons. The author is a forensic psychiatrist and patients currently or previously under her care were excluded from the study, due to potential conflicts of interest. Fifteen subjects were recruited over a two week period from a pool of 21 patients meeting the inclusion criteria. Two of the original 21 were excluded from the study as they were absent during the data collection period and 4 patients declined to participate. Five of the 15 subjects recruited had previously been identified by staff as experiencing psychotic relapses in the context of synthetic cannabinoid use, becoming objectively agitated, disorganized and delusional after smoking the product. The study had ethical approval from the New Zealand Central Regional Ethics Committee. 2.2. Recruitment The interviewer visited the two inpatient units where the research was conducted on 7 occasions. A brief explanation of the study was provided to patients. Subjects who were interested in participating were individually provided with written and oral information about the study and informed oral consent was obtained. 2.3. Interviews Semi-structured interviews were conducted by the author in a private interview room within the inpatient units. The interview explored the subjects’ experience with synthetic cannabinoids, including knowledge, personal use, subjective experience and their observations of how these substances appeared to have affected others. A formal inquiry into each subject’s current mental state was not conducted, but the interviewer noted her observations of the subject’s presentation immediately after the interview, including whether the subject seemed thought disordered. Interviews took place in March and April 2010. 2.4. Data collection and analysis Short-hand notes recording the subjects’ responses were taken during the interview. Patients were not willing to consent to audio recording due to the sensitive nature of the material discussed, and fears about confidentiality. Following the interview, short-hand notes were transcribed into long-hand and were annotated with the interviewer’s observations from the interview. The transcripts were analyzed manually in order to identify key themes and recurrent ideas. Data were coded and indexed in terms of similarity and contrast of content. All data recorded was de-identified to preserve confidentiality. Quotations in Section 3 are used to illustrate emergent trends. Interviewee quotes are identified by: (a) a number between 1 and 15 to differentiate among respondents, and (b) the letter N, O or H to denote the subject’s reported frequency of synthetic cannabinoid use over the preceding year (N: never, O: occasional-less than weekly, H: high use-daily or weekly). 2.5. Urinalysis All patients had been subject to regular random urine drug testing for cannabinoids, opiates, opioids, amphetamines and benzodiazepines.1 The urine drug screen results from the last 18 months were reviewed. 3. Results 3.1. Patient demographics All 15 participating subjects were male. At the time of the study the service had a 5:1 male to female ratio, and no female patients met the inclusion criteria. All patients had a history of psychotic illnesses and had been compulsorily treated with therapeutic doses of antipsychotic medication, with active monitoring of compliance, for at least 6 months prior to the study. Five patients were also taking mood stabilizers. They had all achieved stable mental states prior to the decompensations reported in this study. The demographics of the subjects are summarized in Table 1. All subjects had been within the service for some years, and had been referred to a low security rehabilitation facility as their mental states had improved. They all had unescorted leave off the unit, although in three cases leave privileges had been temporarily revoked due to the patients’ recent deterioration in mental state. All participants had used cannabis in the past. None of the participating patients had tested positive for THC in their most recent urine drug screens. Review of urine drug screens for the cohort over the previous 18 months showed a positive result for cannabinoids was a low probability event. Of 153 urine tests, only 7 (from 1 Random drug screening used an immunoassay technique, based on the KIMs method. Please cite this article in press as: Every-Palmer, S., Synthetic cannabinoid JWH-018 and psychosis: An explorative study. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2011), doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.01.012 G Model DAD-4024; No. of Pages 6 ARTICLE IN PRESS S. Every-Palmer / Drug and Alcohol Dependence xxx (2011) xxx–xxx Table 1 Summary of subject demographics. Feature Sex Male Female Age range Diagnosis Schizophrenia Schizoaffective disorder Bipolar affective disorder with psychotic features Current treatment with antipsychotic medication Index offence Serious violent offence (as defined by NZ Sentencing Act) Non violent offence or violent offence not regarded as serious Lifetime prevalence of cannabis use Positive urine drug screen for cannabis in the last 18 months Number (%) [n = 15] 15 (100%) 0 (0%) Early twenties to mid-forties, mean 34, sd 7.9 10 (67%) 4 (27%) 1 (7%) 15 (100%) 10 (67%) retails at NZ$20/g compared to a cannabis street price of approximately NZ$13.2/g [Wilkins and Sweetsur, 2006]). Patients credited Aroma’s legality, easy availability, product consistency, nondetection in drug tests and perceived safety as reasons to favour it over marijuana. “Aroma has cancelled out all the cannabis here. No one smokes cannabis anymore. Why would you? It [Aroma]’s a good substitute, its legal, it’s not in urine and it’s easier to go to [name of local shop that sells Aroma] than to go down to a tinny house [cannabis dealer].” (8-H) 3.2.2. Psychoactivity. All 13 patients who acknowledged having smoked Aroma said that they used it as a cannabis substitute. “[Aroma]’s like marijuana, but health wise it’s better. . ..It’s strong. It gets you real whacked and makes you high.”(2-H) 5 (33%) 15 (100%) 4 (27%) 4 different patients) were positive for cannabinoids. No patient tested positive for amphetamines or opioids, and positive tests for benzodiazepines and opiates correlated with prescribed medicine. 3.2. Trends On analysis and coding of the interview transcripts four common themes were identified relating to the use of synthetic cannabinoids in the service: their popularity, psychoactivity, effects on mental state and pleasurable feelings of rebellion associated with their use. Results are summarized in Table 2. 3.2.1. Popularity. All subjects were familiar with a locally available SCCP, Aroma. Four patients had some historical experience with similar products called Kronic Skunk, Dream and Spice. All these products consist of a base of unidentified plant matter which has been shown to contain JWH-018 (personal correspondence. Mark Heffernan, Senior Policy Analyst, National Drug Policy, New Zealand Ministry of Health). Of the patients surveyed 87% (13/15) reported having used Aroma over the last year. Of the two clients who denied ever trying SCCPs, one was spontaneously identified by two other clients as being a co-smoker and ‘middleman’ provider of the product to others, casting some doubt over his credibility. Five patients reported high use (daily or almost daily), one reported using weekly, and seven reported infrequent or occasional use (20 times or less in the last year). Most patients reported that SCCPs were more popular than cannabis in the service despite being more expensive (Aroma 3 Five subjects commented that they preferred Aroma to cannabis due to its potency. One subject preferred cannabis and the others were indifferent. A common complaint was that the SCCPs “did not last as long as cannabis”, with the psychoactive effects being consistently described as having a rapid onset of action and a duration of 1–2 h following inhalation. Patients did not know what conferred Aroma its psychoactive properties. Three patients correctly speculated that it ‘had been sprayed with chemicals’, the others were either unsure or described it as a “natural” or “herbal” product. A number of patients commented that it was “safe”, this assumption seemingly based on its legality and easy availability. “I used to smoke marijuana, but I don’t do that when I’m on medication. Aroma won’t interfere with medication. . ..It’s a better buzz than marijuana. It’s quite safe” (10-O) 3.2.3. Effects on mental state. Five patients reported experiences consistent with a psychotic relapse within 24 h of smoking Aroma which lasted “2 days” to “several weeks”. Two of these patients also reported pronounced anxiety symptoms. They attributed these symptoms to Aroma. However, of the 5 patients in this study who had previously been identified by clinical staff as suffering a probable JWH-018-induced psychotic relapse (Every-Palmer, 2010), only 1 subjectively acknowledged the effects Aroma had on their mental state. The other 4 had little insight into their mental illnesses and denied being adversely affected by SCCPs, for example one man who objectively became floridly psychotic and aggressive after admittedly smoking Aroma reported: “Staff say we’re not allowed to smoke it, because it would cause risks, but they don’t know. It doesn’t cause risks to me. It just makes me cool, calm and collected. . . to clients who are sick, it causes risks to them.”(3-O) Table 2 Summary of subjects’ experiences with synthetic cannabinoid containing products (SCCPs). Experience Of all subjects who participated in the study (n = 15) Familiar with synthetic cannabinoid containing products (SCCPs) Admitted using SCCPs over the last year Admitted using SCCP ‘Aroma’ over the last year Admitted using other SCCPs (e.g., Kronic Skunk, Dream, Spice,) Of the subjects who reported SCCP use (n = 13) Described psychoactive effects from SCCP Considered SCCP a “herbal” or “natural” product Reported or exhibited psychotic symptoms following SCCP use Reported observing psychotic symptoms in others following SCCP use Reported experiencing anxiety symptoms following SCCP use Reported tolerance (requiring increasing amounts to achieve the same effects) Reported withdrawal symptoms Yes No Unsure 15/15 (100%) 13/15 (87%) 13/15 (87%) 4/15 (27%) 0/15 (0%) 2/15 (13%) 2/15 (13%) 10/15 (67%) 0/15 (0%) 0/15 (0%) 0/15 (0%) 1/15 (7%) 13/13 (100%) 7/13 (54%) 9/13 (69%) 7/13 (54%) 2/13 (15%) 3/13 (23%) 0/13 (0%) 0/13 (0%) 3/13 (23%) 3/13 (23%) 5/13 (38%) 10/13 (77%) 10/13 (77%) 13/13 (100%) 0/13 (0%) 3/13 (23%) 1/13 (7%) 1/13 (7%) 1/13 (7%) 0/13 (0%) 0/13 (0%) Please cite this article in press as: Every-Palmer, S., Synthetic cannabinoid JWH-018 and psychosis: An explorative study. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2011), doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.01.012 G Model DAD-4024; No. of Pages 6 ARTICLE IN PRESS 4 S. Every-Palmer / Drug and Alcohol Dependence xxx (2011) xxx–xxx Table 3 Patients describe their experience with SCCPs. “I can’t touch it, it makes me real paranoid. . . I smoked a big doobie. Nothing happened for a while. I walked down the street, then started feeling real sick, shaking, dizzy. My heart was pounding and I was freaking out. Then I felt that something bad was leaping out at me. I tried to escape, stumbled onto the road and was almost hit by a car. I was real fucked up.” (10-O) “It made me feel wasted. It made me not feel like myself. I was having psychotic thinking... Wanting to do evil things. It made me think it would be cool to have rocket launches and weapons and stuff. . . In all I smoked under 11[times]. Every time it made me feel not good and those thoughts started coming back. . . I don’t smoke it anymore. . . It’s no good for your brains.” (11-O) “It made me feel like my world was closing in. It made me feel anxious and worried and my heart was pounding. . . It felt weird, I was really warm, really hot, I had never felt that hot before, even in summer. . . I just felt paranoid. . . I smoked cannabis years ago. This was kind of similar, but cannabis never made me feel hot and anxious. I think Aroma’s dangerous.” (15-O) “X and Y used to smoke it with me. They would freak out. He got real paranoid. She used to go off her nut, scream and yell and totally freak out. That would bring the heat on us.” (3-O) “One client, I smoked with him a few times, he’d be completely normal at the start, then he’s just sitting there with his lips moving, talking to someone who’s not even there. Some people take it- they get sick, you know, straight away.” (8-H) Overall 9/13 (69%) of the Aroma users experienced or exhibited psychotic symptoms after using this synthetic cannabinoid. Seven patients also reported that they had noticed other patients become unwell after using Aroma. Descriptions of these experiences are reported in Table 3. 3.2.4. Rebellion. All the patients knew psychoactive substances including SCCPs were prohibited in the service. A number of patients discussed the high level of supervision and loss of autonomy associated with their forensic status, and how they felt that using SCCPs allowed them to reassert their control. “It doesn’t stink, people can’t tell you’ve been smoking it. It never turns up in their tests, so we get away with it, no problems. You can smoke it anywhere. We were smoking it right here, in front of all the nurses. It’s classic, (laughs) they just think its tobacco.” (3-H) 3.2.5. Other themes. Some patients felt SCCP use had negatively affected the atmosphere of the unit. Two non-users talked about other patients spending all their money on SCCPs and then coercing their peers to share cigarettes. Several patients alluded to an ‘ingroup, out-group’ dynamic between users and non-users. A black market had also evolved, with some clients purchasing SCCPs and selling them to others at a profit. 4. Discussion 4.1. Limitations of the study This was a small study (n = 15) of a highly select patient group. The participants were all men with serious mental illness with risk profiles mandating intensive supervision in a forensic service. This group is particularly vulnerable to psychosis, but paradoxically may also currently have some degree of protection (compared to vulnerable people in the community), as all subjects were receiving assertive treatment and environmental support. The experiences of this group cannot necessarily be extrapolated to a wider population, particularly those without mental illness, females and adolescences. This study describes only the subjective experiences that subjects chose to share with the interviewer and as such is subject to bias including selection bias, under-reporting and exaggeration. Although patients and staff report deteriorations in the subjects’ mental states in relation to synthetic cannabinoid use, this study only suggests, but does not prove a causal link. 4.2. Discussion of findings In this cohort of forensic inpatients in a low-secure setting all the subjects were familiar with synthetic cannabinoids and 86% Table 4 Psychoactive compounds detected in Aroma. Compound Concentration Cannibicyclohexanol (mg/g) JWH-018 (mg/g) Oleamide (mg/g) Other psychoactive compounds Not detected 27.91 ± 1.09 210.90 Not detected Source: Uchiyama et al. (2010); Personal correspondence Ruri Kikura-Hanajari, 8 October 2010. reported having used them. They credited the products’ potent psychoactivity, legality, ready availability and non-detection in drug testing as reasons for their popularity, reporting they had replaced cannabis as the drugs of choice in our service. Synthetic cannabinoids do not appear in conventional urine drug testing so users could evade detection and sanction by their care team. This had engendered a conspiratorial culture in which users took some pleasure in small acts of insurrection, in an environment where the balance of power usually resides on the side of the health professionals. Furthermore, most patients assumed SCCPs were “herbal”, “natural” and “safe”. This may be due to by their legality, easy availability and marketing as “organic”. However, synthetic cannabinoids are not herbal, natural nor safe. Nine patients experienced symptoms consistent with a psychotic relapse after using JWH-018 containing products (5 self reported, 4 reported by health professionals). Three patients reported tolerance, but nobody endorsed withdrawal symptoms. Substance abuse is a robust predictor of an increased probability of violence and criminality in the mentally disordered (Soyka, 2000). Whether JWH-018, like cannabis, is a potential mediator of antisocial behaviour is at this stage unclear, but the unfettered use of psychoactive compounds in high risk patients is concerning for both individual and societal reasons. 4.3. Pharmacology of Aroma All patients were smoking the same product, a SCCP marketed as Aroma. This product comprises a dried herb material which is a vehicle for high concentrations of JWH-018 and oleamide. Of 46 products tested by Uchiyama et al. (2010) Aroma contained the highest concentration of oleamide and the second highest concentration of JWH-018. (See Table 4.) 4.4. JWH-018 and psychosis Although to date there is little data about the possible psychiatric sequelae of synthetic cannabinoids, the link between cannabis and psychosis is well established and has been extensively reviewed (e.g., Henquet et al., 2005; Fergusson et al., 2006; Moore Please cite this article in press as: Every-Palmer, S., Synthetic cannabinoid JWH-018 and psychosis: An explorative study. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2011), doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.01.012 G Model DAD-4024; No. of Pages 6 ARTICLE IN PRESS S. Every-Palmer / Drug and Alcohol Dependence xxx (2011) xxx–xxx et al., 2007; Murray et al., 2007). Cannabis contains at least 90 different cannabinoids, with THC being the primary psychoactive ingredient (Gaoni and Mechoulam, 1964). In experimental studies, THC produces transient and dose related psychotic symptoms (D’Souza et al., 2004) and impaired memory (Solowij and Michie, 2007). Consumer surveys (e.g., Thomas, 1996) provide further evidence that cannabis intoxication can produce transient psychotic experiences. Large prospective epidemiological studies (e.g., van Os et al., 2002; Zammit et al., 2002; Arseneault et al., 2002) show a link between cannabis use and the development of chronic psychotic illnesses such as schizophrenia. All the patients in this study had established psychotic illnesses. Cannabis use in such patients is common (Green et al., 2004; Boydell et al., 1999) and has been associated with poor clinical and functional outcomes including: an earlier disease onset (Foti et al., 2010); more positive symptoms (Bühler et al., 2002; Mauri et al., 2006); a higher relapse rate (Swofford et al., 1996), and a reduced treatment response (Foti et al., 2010). In first-episode schizophrenia cannabis use is associated with a greater reduction in cerebral grey matter volume in users compared with non users over time (Rais et al., 2008). It cannot be assumed that the psychiatric risks of synthetic cannabinoids will equate to those associated with cannabis, however, it is hypothesized that JWH-018 may pose comparable or even greater risks due to the following observations: 1. JWH-018 produces similar effects to THC in animal experiments (EMCDDA, 2009). 2. There are an emerging number of reports of users experiencing psychotic symptoms in the context of JWH-018 use on the internet and in the literature (Müller et al., 2010; Every-Palmer, 2010). 3. The pharmacological profile of JWH-018 raises the theoretical possibility of increased cognitive and psychiatric side effects compared to cannabis. (a) In vitro data suggests that JWH-018 possesses approximately a four-fold higher affinity to the CB1 receptor and ten-fold affinity to CB2 receptor compared with THC (Aung et al., 2000; Huffman et al., 2005). CB1 receptors are abundant in central nervous system, particularly in the basal ganglia, hippocampus and cerebellum (Howlett et al., 2004; Fergusson et al., 2006). These receptors regulate the release of several key neurotransmitters, including dopamine and serotonin. It is thought that cannabis may lead to psychosis through THCs’s effects on dopaminergic and serotonergic pathways via CB1 receptors (Fergusson et al., 2006). While THC exerts only partial CB1 agonism, JWH-018 is a full and potent agonist at CB1 receptors (Atwood et al., 2010). (b) Unlike cannabis, SCCPs do not contain cannabidiol. Cannabidiol and THC are the two major components of cannabis, and they exhibit opposing pharmacological and physiological actions. Cannabidiol is a CB1 and CB2 antagonist which appears to have antipsychotic (Leweke et al., 2009; Zuardi et al., 2006; Morgan and Curran, 2008) and anxiolytic properties (Guimarães et al., 1990) and may be neuroprotective in humans (Hermann et al., 2007; Morgan et al., 2010). While cannabidiol may afford cannabis users some inherent protection against psychotic symptoms (Morgan and Curran, 2008) and cognitive impairment (Morgan et al., 2010) this protection is lacking in SCCPs. (c) Some SCCPs like Aroma also contain oleamide, a fatty acid demonstrated to functionally activate CB1 cannabinoid receptors in vitro (Leggett et al., 2004), which may have potentiating effects. 4. SCCPs may appeal to vulnerable populations who might not otherwise smoke cannabis including those who have suf- 5 fered adverse effects from cannabis or have been warned against using cannabis (e.g., a possible predisposition to psychotic illness) and those being monitored for drug use (e.g., in prisons, forensic hospitals). There are increasing reports of young people using SCCPs (e.g., EMCDDA, 2009; http://www.stuff.co.nz/national/4279640/Parents-worried-bylegal-weed). In the forensic population studied in this research, the base rate of ongoing cannabis use was low due to institutional deterrents and education regarding the risks of cannabis. However, those disincentives did not exist to the same extent with SCCPs, which were being consumed in greater quantities than cannabis had previously been. Although it is likely that most people who smoke SCCPs will not experience psychotic symptoms, the risks are much higher for these vulnerable populations. 4.5. Management It is known that in forensic populations drug treatment programs associated with the best outcomes are assertive and use some form of leverage, such as mandatory drug testing (Lamb et al., 1999). Currently there are no widely available drug testing methods to identify JWH-018 use, although laboratory techniques have recently been developed for identifying JWH-018 in serum (Teske et al., 2010) and JWH-018 metabolites in urine (Sobolevsky et al., 2010). Until these techniques become more widely available clinicians will need to rely on clinical skills. These include: specifically asking patients about “herbal highs”; being alert to the physiological and effects of SCCP use such as conjuctival injection and tachycardia (Auwärter et al., 2009; Sobolevsky et al., 2010) and having a high index of suspicion in the context of an unexplained deterioration in mental state in the context of a negative urine drug screen. Health professionals need to be cogniscant and responsive to novel drug trends in order to counsel their clients appropriately. In countries where synthetic cannabinoids remain legal, there needs to be ongoing review and monitoring of their safety at a national level. Discussion also needs to be held around the accurate labeling of products containing psychoactive compounds, so that users are aware of the potential risks. 5. Conclusion Synthetic cannabinoids pose difficult social, political and health challenges. There are more than 100 known compounds with cannabinoid receptor activity, and no doubt more will be synthesized in the future. Almost nothing is known about the pharmacology and toxicology of compounds such as JWH-018, however, it seems that they can cause psychosis in vulnerable individuals. Health professionals need to maintain a high degree of vigilance for novel substance use, and the possible psychiatric consequences. People with risk factors for psychosis should be counseled against using synthetic cannabinoids. Role of funding source Nothing declared. Conflict of interest No conflict declared. Acknowledgements With grateful thanks to all the subjects who gave up their time to participate in this research, to Mark Heffernan from the New Please cite this article in press as: Every-Palmer, S., Synthetic cannabinoid JWH-018 and psychosis: An explorative study. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2011), doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.01.012 G Model DAD-4024; No. of Pages 6 6 ARTICLE IN PRESS S. Every-Palmer / Drug and Alcohol Dependence xxx (2011) xxx–xxx Zealand Ministry of Health who peer reviewed this manuscript and to Dennis Klue, Nigel Fairley, Dr Justin Barry-Walsh, Dr Joanna MacDonald and Professor Pete Ellis for their support. References Arseneault, L., Cannon, M., Poulton, R., Murray, R., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T.E., 2002. Cannabis use in adolescence and risk for adult psychosis: longitudinal prospective study. BMJ 325, 1212–1213. Atwood, B.K., Huffman, J., Straiker, A., Mackie, K., 2010. JWH018, a common constituent of ‘Spice’ herbal blends, is a potent and efficacious cannabinoid CB1 receptor agonist. Br. J. Pharmacol. 160, 133–140. Aung, M.M., Griffin, G., Huffman, J.W., Wu, M., Keel, C., Yang, B., Showalter, V.M., Abood, M.E., Martin, B.R., 2000. Influence of the N-1 alkylchain length of cannabimimetic indoles upon CB(1) and CB(2)receptor binding. Drug Alcohol Depend. 60, 133–140. Auwärter, V., Dresen, S., Weinmann, W., Müller, M., Pütz, M., Ferreirós, N., 2009. Spice and other herbal blends: harmless incense or cannabinoid designer drugs? J. Mass Spectrom. 44, 832–837. Banerji, S., Deutsch, C.M., Bronstein, A.C., 2010. Spice ain’t so nice [abstract]. Clin. Toxicol. (Phila.) 48, 632. Bebarta, V.S., Varney, S., Sessions, D., Barry, D., Borys, D., 2010. Spice: a new “legal” herbal mixture abused by young active duty military personnel [abstract]. Clin. Toxicol. (Phila.) 48, 632. Boydell, J., van Os, J., Caspi, A., Kennedy, N., Giouroukou, E., Fearon, P., Farrell, M., Murray, R.M., 2006. Trends in cannabis use prior to first presentation with schizophrenia, in South-East London between 1965 and 1999. Psychol. Med. 36, 1441–1446. Bühler, B., Hambrecht, M., Löffler, W., an der Heiden, W., Häfner, H., 2002. Precipitation and determination of the onset and course of schizophrenia by substance abuse – a retrospective and prospective study of 232 population-based first illness episodes. Schizophr. Res. 54, 243–251. D’Souza, D.C., Perry, E., MacDougall, L., Ammerman, Y., Cooper, T., Wu, Y.T., Braley, G., Gueorguieva, R., Krystal, J.H., 2004. The psychotomimetic effects of intravenous delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in healthy individuals: implications for psychosis. Neuropsychopharmacology 29, 1558–1572. Dresen, S., Ferreirós, N., Pütz, M., Westphal, F., Zimmermann, R., Auwärter, V., 2010. Monitoring of herbal mixtures potentially containing synthetic cannabinoids as psychoactive compounds. J. Mass Spectrom. 45, 1095–1232. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), 2009. Understanding the ‘Spice” phenomenon. Available at: http://www.emcdda.europa. eu/attachements.cfm/att 80086 EN Spice%20Thematic%20paper%20%E2%80% 94%20final%20version.pdf Last checked 15 October, 2010. Every-Palmer, S., 2010. Warning: legal synthetic cannabinoid-receptor agonists such as JWH 018 may precipitate psychosis in vulnerable individuals. Addiction 105, 1859–1860. Fergusson, D.M., Poulton, R., Smith, P.F., Boden, J.M., 2006. Cannabis and psychosis. BMJ 332, 172–175. Foti, D.J., Kotov, R., Guey, L.T., Bromet, E.J., 2010. Cannabis use and the course of schizophrenia: 10-year follow-up after first hospitalisation. Am. J. Psychiatry 167, 987–993. Gaoni, Y., Mechoulam, R., 1964. Isolation, structure and partial synthesis of an active constituent of hashish. J. ACS 86, 1646–1647, available at: http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/ja01062a046. Last checked 10 October. Green, A.I., Tohen, M.F., Hamer, R.M., Strakowski, S.M., Lieberman, J.A., Glick, I., Clark, W.S., 2004. First episode schizophrenia-related psychosis and substance use disorders: acute response to olanzapine and haloperidol. Schizophr. Res. 66, 125–135. Griffiths, P., Sedefov, R., Gallegos, A., Lopez, D., 2010. How globalization and market innovation challenge how we think and respond to drug use: ‘Spice’ a case study. Addiction 105, 951–953. Guimarães, F.S., Chiaretti, T.M., Graeff, F.G., Zuardi, A.W., 1990. Antianxiety effect of cannabidiol in the elevated plus-maze. Psychopharmacology 100, 558–559. Henquet, C., Murray, R., Linszen, D., van Os, J., 2005. The environment and schizophrenia: the role of cannabis use. Schizophr. Bull. 31, 608–612. Hermann, D., Sartorius, A., Welzel, H., Walter, S., Skopp, G., Ende, G., Mann, K., 2007. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex N-acetyl-aspartate/total creatine (NAA/tCr) loss in male recreational cannabis users. Biol. Psychiatry 61, 1281–1289. Howlett, A.C., Breivogel, C.S., Childers, C.R., 2004. Cannabinoid physiology and pharmacology: 30 years of progress. Neuropharmacology 47, 345–358. Hudson, S., Ramsey, J., King, L., Timbers, S., Maynard, S., Dargan, P.I., Wood, D.M., 2010. Use of high-resolution accurate mass spectrometry to detect reported and previously unreported cannabinomimetics in “herbal high” products. J. Anal. Toxicol. 34, 252–260. Huffman, J.W., Zengin, G., Wu, M.J., Lu, J., Hynd, G., Bushell, K., Thompson, A.L.S., Bushell, S., Tartal, C., Hurst, D.P., Reggio, P.H., Selley, D.E., Cassidy, M.P., Wiley, J.L., Martin, B.R., 2005. Structure–activity relationships for 1-alkyl-3(1-naphthoyl)indoles at the cannabinoid CB(1) and CB(2) receptors: steric and electronic effects of naphthoyl substituents. New highly selective CB(2) receptor agonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 13, 89–112. Lamb, H.R., Weinberger, L.E., Gross, B.H., 1999. Community treatment of severely mentally ill offenders under the jurisdiction of the criminal justice system: a review. Psychiatr. Serv. 50, 907–913. Leggett, J.D., Aspley, S., Beckett, S.R.G., D’Antona, A.M., Kendall, D.A., Kendall, D.A., 2004. Oleamide is a selective endogenous agonist of rat and human CB1 cannabinoid receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 141, 253–262. Leweke, F.M., Koethe, D., Pahlisch, F., Schreiber, D., Gerth, C.W., Nolden, B.M., Klosterkötter, J., Hellmich, M., Piomelli, D., 2009. S39-02 Antipsychotic effects of cannabidiol. Eur. Psychiatry 24, S207. Lindigkeit, R., Boehme, A., Eiserloh, I., Luebbecke, M., Wiggermann, M., Ernst, L., Beuerle, T., 2009. Spice: a never ending story? Forensic Sci. Int. 191, 58–63. Mauri, M.C., Volonteri, L.S., De Gaspari, I.F., Colasanti, A., Brambilla, M.A., Cerruti, L., 2006. Substance abuse in first-episode schizophrenic patients: a retrospective study. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 23 (2), 4. Moore, T.H.M., Zammit, S., Lingford-Hughes, A., Barnes, T.R.E., Jones, P.B., Burke, M., Lewis, G., 2007. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Lancet 370, 319–328. Morgan, C.J.A., Curran, H.V., 2008. Effects of cannabidiol on schizophrenia-like symptoms in cannabis users. Br. J. Psychiatry 192, 306–307. Morgan, C.J.A., Schafer, G., Freeman, T.P., Curran, H.V., 2010. Impact of cannabidiol on the acute memory and psychotomimetic effects of smoked cannabis: naturalistic study. Br. J. Psychiatry 197, 285–290. Müller, H., Sperling, W., Köhrmann, M., Huttner, H.B., Kornhuber, J., Maler, J.M., 2010. The synthetic cannabinoid Spice as a trigger for an acute exacerbation of cannabis induced recurrent psychotic episodes. Schizophr. Res. 118, 309–310. Murray, R.M., Morrison, P.D., Henquet, C., Di Forti, M., 2007. Cannabis, the mind and society: the hash realities. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 885–895. New Zealand Department of Corrections, 1999. The National Study of Psychiatric Morbidity in New Zealand Prisons, available at http://www.corrections. govt.nz/research/national-study-psychiatric-morbidity-in-nz-prisons.html Last accessed 15 October 2010. Piggee, C., 2009. Investigating a not-so-natural high. Anal. Chem. 81, 3205–3207. Rais, M., Cahn, W., Van Haren, N., Schnack, H., Caspers, E., Hulshoff Pol, H., Kahn, R., 2008. Excessive brain volume loss over time in cannabis-using first-episode schizophrenia patients. Am. J. Psychiatry 165, 490–496. Sobolevsky, T., Prasolov, I., Rodchenkov, G., 2010. Detection of JWH-018 metabolites in smoking mixture post-administration urine. Forensic Sci. Int. 200, 141–147. Solowij, N., Michie, P.T., 2007. Cannabis and cognitive dysfunction: parallels with endophenotypes of schizophrenia? J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 32, 30–52. Soyka, M., 2000. Substance misuse, psychiatric disorder and violent and disturbed behaviour. Br. J. Psychiatry 1761, 345–350. Swofford, C.D., Kasckow, J.W., Scheller-Gilkey, G., Inderbitzin, L.B., 1996. Substance use: a powerful predictor of relapse in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 20, 145–151. Teske, J., Weller, J.P., Fieguth, A., Rothämel, T., Schulz, Y., Tröger, H.D., 2010. Sensitive and rapid quantification of the cannabinoid receptor agonist naphthalen1-yl-(1-pentylindol-3-yl)methanone (JWH-018) in human serum by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B: Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 878, 2659–2663. Thomas, H., 1996. A community survey of adverse effects of cannabis use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 42, 201–207. Uchiyama, N., Kikura-Hanajiri, R., Kawahara, N., Haishima, Y., Goda, Y., 2009. Identification of a cannabinoid analog as a new type of designer drug in a herbal product. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 57, 439–441. Uchiyama, N., Kikura-Hanajiri, R., Ogata, J., Goda, Y., 2010. Chemical analysis of synthetic cannabinoids as designer drugs in herbal products. Forensic Sci. Int. 198, 31–38. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report, 2010. Available at http://www.unodc.org/documents/wdr/WDR 2010/World Drug Report 2010 lo-res.pdf Last accessed on 1 October 2010. United States Drug Enforcement Administration, Office of Forensic Sciences, 2009. ‘Spice’—plant material(s) laced with synthetic cannabinoids or cannabinoid mimicking compounds. Microgram Bulletin. 42(3). Available at: http://www. justice.gov/dea/programs/forensicsci/microgram/mg0309/mg0309.html Last accessed 1 October 2010. van Os, J., Bak, M., Hanssen, M., Bijl, R.V., de Graaf, R., Verdoux, H., 2002. Cannabis use and psychosis: a longitudinal population-based study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 156, 319–327. Vardakou, I., Pistos, C., Spiliopoulou, Ch., 2010. Spice drugs as a new trend: mode of action, identification and legislation. Toxicol. Lett. 197, 157–162. Vearrier, D., Osterhoudt, K.C., 2010. A teenager with agitation: higher than she should have climbed. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 26, 462–465. Wilkins, C., Sweetsur, P., 2006. Exploring the structure of the illegal market for cannabis. De Economist 154, 547–562. Zammit, S., Allebeck, P., Andreasson, S., Lundberg, I., Lewis, G., 2002. Self-reported cannabis use as a risk factor for schizophrenia in Swedish conscripts of 1969: historical cohort study. BMJ 325, 1199–1201. Zimmermann, U.S., Winkelmann, P.R., Pilhatsch, M., Nees, J.A., Spanagel, R., Schulz, K., 2009. Withdrawal phenomena and dependence syndrome after the consumption of “Spice Gold”. Dtsch. Artzebl. Int. 106, 464–467. Zuardi, A.W., Crippa, J.A., Hallak, J.E., Moreira, F.A., Guimarães, F.S., 2006. Cannabidiol, a Cannabis sativa constituent, as an antipsychotic drug. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 39, 421–429. Please cite this article in press as: Every-Palmer, S., Synthetic cannabinoid JWH-018 and psychosis: An explorative study. Drug Alcohol Depend. (2011), doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.01.012