* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download A Case Report of Neutrophilic Eccrine Hidradenitis in a Patient

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

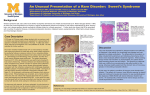

860 NEH in AML—G C Wong et al A Case Report of Neutrophilic Eccrine Hidradenitis in a Patient Receiving Chemotherapy for Acute Myeloid Leukaemia G C Wong,*MBBS, MRCP (UK), M Med (Int Med), L H Lee,**FAMS, MBBS, M Med, Y Y Chong,***FAMS, MBBS Abstract Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis (NEH) is a neutrophilic dermatosis primarily affecting the eccrine glands and occurs in patients undergoing chemotherapy. It must be distinguished from infections, drug eruptions, leukaemia cutis or other forms of skin diseases. As it is self-limiting, establishing the diagnosis will avoid unnecessary treatment for infections or changes in drug therapy. Ann Acad Med Singapore 1998; 27:860-3 Key words: Eccrine glands, Infection, Malignancy, Neutropenic, Self-limiting Introduction Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis (NEH) is a neutrophilic dermatosis primarily affecting the eccrine glands and occurs most commonly in patients undergoing chemotherapy for a malignancy. This was first described by Harrist et al1 in 1982 and Flynn et al2 in 1984. These cases occurred in men who were receiving cytarabine-containing induction chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukaemia (AML). Since then, other drugs such as bleomycin, 3-5 mitoxantrone, 6,7 chlorambucil, 8 zidovudine9 and acetaminophen 10 have also been implicated. As NEH is most frequently seen in patients receiving chemotherapy, it must be distinguished from disseminated infection, drug hypersensitivity eruptions, leukaemia cutis or other cutaneous metastases, Sweet’s syndrome, erythema multiforme, vasculitis, bullous pyoderma and pyoderma gangrenosum.1,2,11,12 Therefore, establishing the diagnosis of NEH is important to avoid unnecessary treatment for infections or changes in therapy for non-existent drug reactions. We describe a patient with AML who developed NEH on receiving high-dose cytarabine for consolidation chemotherapy. Case Report A 41-year-old man presented with a one-month history of bleeding gums associated with fever, chills and rigors. He was pancytopenic (haemoglobin 9 g%, total white (Tw) 2000/cm3, polymorphs 15%, lymphocytes 75%, blasts 7%, platelets (P) 48,000/cm3) and was diagnosed to have AML. He received induction chemotherapy with high-dose cytarabine (1.5 g/m2 for four days) and idarubicin (12 mg/m2 for two days) and went into remission. He then received idarubicin (12 mg/m2 for two days) and cytarabine (100 mg/m2 for seven days) as the first consolidation chemotherapy. This was complicated by a perianal abscess and fistula which were treated with antibiotics and fistulotomy. He was next given cytarabine 1.5 g/m2 continuous infusion for four days as second consolidation chemotherapy. On the second day of the infusion, the patient developed a generalised maculopapular rash which was attributed to cytarabine. His full blood count was normal. The rash resolved with prednisolone. The patient subsequently developed a fever on the third day and was started on cefuroxime and gentamicin and later ciprofloxacin. Vancomycin and flagyl were added when the temperature rose again on day 10. The patient was neutropenic from day 5 to day 14 post chemotherapy. Imipenem, amikacin, azithromycin were ordered and the patient was also started on empiric amphotericin on day 15. He was on granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) from day 14. On day 16 (Tw 1400 /cm3, P 54%), he became febrile and developed a non-tender, non-pruritic maculopapular rash with monomorphic vesicles on the thighs, limbs, neck and trunk (Figs. 1 & 2). * Registrar ** Consultant Department of Haematology *** Consultant Department of Pathology Singapore General Hospital Address for Reprints: Dr G C Wong, Department of Haematology, Singapore General Hospital, 1 Hospital Drive, Singapore 169608. Annals Academy of Medicine NEH in AML—G C Wong et al Fig. 1. Maculopapular rash with vesicles on patient’s forearm and hand. There was no oro-mucosal lesions. The differential diagnoses included drug eruption and disseminated herpes infection for which acyclovir was started. A skin biopsy showed several foci of neutrophils, lymphocytes and histiocytes associated with nuclear dust in the upper dermis and few neutrophilic infiltrates within the sweat ducts (Fig. 3). Mycobacterial, bacterial and fungal cultures were all negative. Tzanck test was also negative. This was diagnosed as neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis on biopsy. The rash subsided over the next four days. Meanwhile the patient’s counts recovered and he was discharged two weeks later, well and afebrile. He had been on regular follow-up and had remained in remission. Discussion Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis is a neutrophilic dermatosis primarily affecting the eccrine glands, and most commonly seen in patients undergoing chemotherapy for treatment of a malignancy. This was first described by Harrist et al1 in 1982 and Flynn et al2 in 1984. Drugs implicated include bleomycin,3 mitoxantrone,6 chlorambucil, zidovudine and acetaminophen though NEH was first attributed to cytarabine.1,2 Malignancies November 1998, Vol. 27 No. 6 861 Fig. 2. Vesicular rash on back of patient’s neck. Fig. 3. Skin biopsy showing foci of neutrophils, lymphocytes and histiocytes associated with nuclear dust in the upper dermis and few neutrophilic infiltrates within the sweat dusts. associated with NEH include acute myeloid leukaemia, acute myelomonocytic leukaemia,1-3 testicular carcinoma,3 Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and osteogenic sarcoma. Our patient received high-dose cytarabine as induction chemotherapy and 1 consolidation therapy with standard dose cytarabine without 862 NEH in AML—G C Wong et al developing a rash. It was only on second exposure to highdose cytarabine that he developed NEH. This is similar to a patient reported by Margolis and Gross6 who developed NEH to high-dose cytarabine and not to low-dose cytarabine. Whether the development of NEH is related to the dose of chemotherapy or to the number of times of exposure to the drug has not been reported so far. Our patient developed the rash when he was neutropenic. This was also seen in patients reported by Bernstein et al13 and Margolis and Gross.6 Most cases of NEH have occurred in neutropenic patients, hence this condition is often regarded by dermatologists to represent a pathologically distinct, benign self-limited drug reaction that occurs in neutropenic patients.6 However, 1 patient described by Kuttner and Kurban10 did not have a white blood cell abnormality due to a primary disease or a drug-induced process. This patient was immunologically competent and developed NEH after taking acetaminophen. The eruption resolved quickly after the drug was discontinued. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis may, therefore, not be restricted to patients with cancer or neutropenic patients. Our patient first developed a rash on the second day of the cytarabine infusion which was attributed to cytarabine itself. This subsided very quickly. He next developed a rash on day 16 post chemotherapy. This proved eventually to be neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis on biopsy and the rash resolved spontaneously. In the thirteen episodes of NEH reported where cytarabine was the inciting agent, the rash occurred on average 9.3 days later. Our patient developed the rash much later. Four out of eight patients developed a recurrence of the eruption1-3 when the inciting chemotherapeutic agent was readministered. Our patient, however, only developed NEH on his third exposure to cytarabine. Our patient was febrile during the episode of NEH. However, he was neutropenic then and was on antibiotics. Infections and drug rash were considered likely. Cultures failed to reveal any organisms and biopsy proved the rash to be due to NEH. Eight patients cited in the literature were pyrexial at the time of their presentation with NEH. All were receiving chemotherapy for the treatment of malignancy and were at risk of infection.1,4,6,8,11,12-14 In none of these eight patients was a source of infection noted. Spontaneous resolution is the rule with NEH.4 This was also the case in our patient. However, in the patient reported by Bernstein et al,15 the lesions were painful and their persistence prompted the use of intravenous corticosteroids. Both the lesions and fever resolved within 24 hours. Care must be taken in the decision to give steroids to an already immunocompromised host in such setting. It has also been reported that leukocyte colony-stimu- lating factors can induce neutrophilic dermatoses and necrotizing vasculitis.16 It was observed by Johnson et al16 that the eruptions consistently developed after 1 to 2 weeks of colony-stimulating factor administration and that prompt cessation of these factors is often sufficient for resolution of the rash. Our patient received G-CSF from day 14 and his rash developed 2 days later on day 16 and resolved over the next 4 days, despite the patient being still on G-CSF. We feel that the rash is less likely to be due to G-CSF as it started just 2 days after G-CSF administration and resolved spontaneously despite continuation of G-CSF. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis can either present in a localised distribution involving the limbs or trunk17 or be generalised.6,9,11 In our patient, the rash was generalised involving the limbs and trunk. There could be a difference in morphology and distribution and this is not dependent upon the chemotherapeutic agent administered.15 The true pathophysiological mechanism responsible for NEH has not been well delineated. Numerous substances have been shown to be chemotactic for neutrophils such as complement component C5a, hydroxyeicosatetranoic acids (HETE), interleukin 1, platelet factor and activating factor, platelet-derived growth factor and others.15 The infiltrate in most specimens was composed almost entirely of neutrophils, despite the patients being neutropenic in most of the cases. Hence, the stimulus attracting the neutrophils to attack the eccrine glands and coils is very potent.15 It has also been speculated that this represents a specific drug reaction to a chemotherapeutic agent.2,12 These agents are believed to be preferentially secreted in the eccrine coil causing the neutrophilic response.12 However, there are patients who manifested NEH only once despite the drug being used more than once in the treatment regime. It is also difficult to examine the true incidence of this disease since it resolves without an alternation in treatment. Therefore, NEH probably represents an underreported benign drug reaction that occurs primarily with neutropenic patients. It does not appear to be lifethreatening and abates without any changes in drug therapy. In conclusion, NEH is a neutrophilic dermatosis seen most frequently in patients receiving chemotherapy for the treatment of a malignancy. It occurs most often in neutropenic patients who may or may not be febrile and who may be on multiple drugs. Infections and antibiotic drug rash are the most frequent differentials. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis should be considered as this is often self-limiting and non life-threatening and should not lead to withdrawal of appropriate antibiotics for treatment of infection. Annals Academy of Medicine NEH in AML—G C Wong et al REFERENCES 863 9. Smith K J, Skelton H G III, James W D, Holland T T, Lupton G P, Angritt P. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis in HIV-infected patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990; 23:945-7. 1. Harrist T J, Fine J D, Berman R S, Murphy G F, Mihm M C Jr. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis. A distinctive type of neutrophilic dermatosis associated with myelogenous leukemia and chemotherapy. Arch Dermatol 1982; 118:263-6. 10. Kuttner B J, Kurban R S. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis in the absence of an underlying malignancy. Cutis 1988; 41:403-5. 2. Flynn T C, Harrist T J, Murphy G F, Loss R W, Moschella S L. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis: a distinctive rash associated with cytarabine therapy and acute leukemia. J Am Acad Dermatol 1984; 11:584-90. 11. Katsanis E, Luke K-H, Hsu E, Carpenter B F, Mantynen P R. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis in acute myelomonocytic leukemia. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 1987; 9:204-8. 3. Fitzpatrick J E, Bennion S D, Reed O M, Wilson T, Reddy V V, Golitz L. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis associated with induction chemotherapy. J Cutan Pathol 1987; 14:272-8. 12. Bailey D L, Barron D, Lucky A W. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol 1989; 6:33-8. 4. Beutner K R, Packman C H, Markowitch W. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis associated with Hodgkin’s disease and chemotherapy: a case report. Arch Dermatol 1986; 122:809-11. 5. Scallan P J, Kettler A H, Levy M L, Tschen J A. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis: evidence implicating bleomycin as a causative agent. Cancer 1988; 62:2532-6. 6. Margolis D J, Gross P R. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis 1991; 48:198-200. 7. Burg G, Bieber T, Langecker P. Lokalisierte neutrophile eccrine Hidradenitis unter Mitoxantron: Eine typische zytostatikanebenwirkung. Hautarzt 1988; 39:233-6 (German) (English abstract). 8. Fernandez Cogolludo E, Ambrojo Antune Z P, Aguilar Martinez A, Pena Payero M L, Sanchez-Yus-E. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis—a report of two additional cases. Clin Exp Dermatol 1989; 14:341-6. November 1998, Vol. 27 No. 6 13. Scherberiske J M, Benson P M, Lupton G P. Asympt erythematous papules in a leukemic patient. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis. Arch Dermatol 1990; 126:528-32. 14. Scong V Y, Appell M L, Sanders D Y, Omura E F. Annular plaques on the dorsa of the hands. Arch Dermatol 1991; 127:1398-9, 1400-2. 15. Bernstein E F, Spielrogel R L, Topolsky D L. Recurrent neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis. Br J Dermatol 1992; 127:529-33. 16. Johnson M L, Grimwood R E. Leukocyte colony-stimulating factors. A review of associated neutrophilic dermatoses and vasculitides. Arch Dermatol 1994; 130:77-81. 17. Hurt M A, Halvorson R D, Petr F C Jr, Cooper J T, Friedman D J. Eccrine squamous syringometaplasia: a cutaneous sweat gland reaction in the histologic spectrum of ‘chemotherapy-associated eccrine hidradenitis’ and ‘neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis’. Arch Dermatol 1990; 126:73-7.