* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

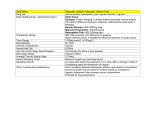

Download 1: gastro-intestinal system

Pharmacokinetics wikipedia , lookup

Drug discovery wikipedia , lookup

Neuropsychopharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Pharmaceutical industry wikipedia , lookup

Drug interaction wikipedia , lookup

Neuropharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Adherence (medicine) wikipedia , lookup

Psychopharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Pharmacognosy wikipedia , lookup

Prescription costs wikipedia , lookup

Pharmacogenomics wikipedia , lookup

Theralizumab wikipedia , lookup

Dydrogesterone wikipedia , lookup

Discovery and development of proton pump inhibitors wikipedia , lookup