* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download YEAR 3: ANCIENT GREECE (5 lessons)

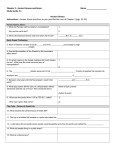

Regions of ancient Greece wikipedia , lookup

Athenian democracy wikipedia , lookup

Economic history of Greece and the Greek world wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek literature wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek religion wikipedia , lookup

Greco-Persian Wars wikipedia , lookup

Peloponnesian War wikipedia , lookup

First Peloponnesian War wikipedia , lookup

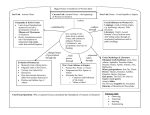

YEAR 3: ANCIENT GREECE (5 lessons) Contents Include: Greek City States Athens Sparta The Persian Wars Marathon and Thermopylae Suggested Teacher Resources: A Little History of the World by Ernst Gombrich (chapters 7, 8, 9 and 10). Ancient Greece by Andrew Solway (illustrated by Peter Connolly). The BBC has a section on teaching Ancient Greece in the primary school, with lots of images and information. Click here. Scenes from films such as 300 (2006), Troy (2004), and Alexander (2004). Lesson 1. An introduction to Ancient Greece The aim of this lesson is to give pupils an overview of Ancient Greece . The Ancient Greek civilisation emerged after 800 BC, and reached its peak around 330 BC with the conquests of Alexander the Great. Ancient Greece was made up of individual city states, which frequently fought between each other. However, all of the city states shared a similar language, and a similar Greek culture involving Gods, myths and sports. Ancient Greece was not one country, but it was one civilisation. Where pupils may have existing knowledge of Ancient Greece, from films and popular culture, this should be drawn out. See pages 148-149 of What Your Year 3 Child Needs to Know. Learning Objective To begin to understand life in Ancient Greece. Core Knowledge Ancient Greece was made up of a series of independent city-states such as Athens and Sparta. Although Ancient Greece was made up of many separate states, they all shared a similar culture, with common Gods, myths and the Olympic Games. The Olympic Games saw each of the independent city-states compete against each other at sports every four years. Activities for Learning Show images for each aspect of Ancient Greece covered on resource 1 which may appeal to pupils’ existing knowledge, such as The Olympics, 300 (2006), Troy (2004), Alexander (2004), Greek Gods, the Parthenon. Annotate a map of Ancient Greece. This should show much of what the pupils will go on to study (resource 1). The map of Ancient Greece can be found here. This and this are Horrible Histories videos on the Ancient Greek Olympics. This is a clip from the BBC. Related Vocabulary Assessment Questions civilisation independent city-state Olympic Games Was Ancient Greece all one country? What is an independent city state? What did the city states share? What have the Ancient Greeks given us that we still enjoy today? 1. Ancient Greece Macedonia Athens Troy Olympia Mount Olympus Sparta Crete 1. Ancient Greece (complete) Athens Macedonia The most famous of the Greek city-states. It was the home of democracy, where people were allowed to vote for their own rulers. It is now the capital city of Greece. The home of Alexander the Great, the greatest military commander of Ancient Greece. Troy Site of the famous war, between the Greeks and the Trojans, which ended with the building of a wooden horse. Olympia The site of the original Olympic Games, where all of the different Greek citystates would compete. Mount Olympus Sparta Another city-state, famous for developing the greatest warriors of Ancient Greece. Crete The largest of the Greek islands, and the mythical home of King Minos and the Minotaur. The highest mountain in Greece and the mythical home of the twelve Greek Gods. The Gods were like humans, but eternal, and lived in a cloud palace. Lesson 2. Athens: Birthplace of Democracy Athens is famous throughout the world for having been the first state to have been governed according to democratic principles. However, it was not democracy as we know it. Britain is a representative democracy, where Members of Parliament are elected every five years to represent a local area. Athens was a direct democracy, where every decision taken by the ruling council could be approved or vetoed by citizens. It should be emphasised that citizens made up only a small minority of Athens’ population, as slaves and women were not allowed to vote. See pages 149-150 of What Your Year 3 Child Needs to Know. Learning Objective Core Knowledge To understand how democracy in Athens worked. Athens was the birthplace of Democracy, meaning ‘rule by the people’. The meaning and origin of some key words (vote, democracy, tyrant) should be covered at the start of the lesson. All citizens in Athens were allowed to vote. However, this meant that women and slaves (who did not qualify as citizens) were not allowed to do vote. Pupils act out Athenian Democracy, according to a teacher’s script (resource 2). This should help them to understand how democracy worked in Athens. The people of Athens did not have to suffer being ruled by a ‘tyrant’, as they could simply get rid of their leaders through a popular vote. This was known as ‘ostracising’. Activities for Learning This is an image of the pnyx, on which speakers would stand to address Athenian citizens, and this is an image of the acropolis, the civic centre of ancient Athens. This is a good video about the Acropolis in Athens, this is about the Parthenon, and this is about the birth of democracy. Related Vocabulary tyrant democracy vote boule ecclesia pnyx Assessment Questions What was a tyrant? What does democracy mean? Who was allowed to vote in Athens? How did Athenian Democracy work? 2. Athenian Democracy The class will be acting out Athenian Democracy. This was a form of direct democracy, where all laws could be approved or vetoed by citizens. The ruling council was known as the Boule, and all of their decisions could be voted upon by the assembly of citizens, known as the Ecclesia. To complete this activity, you will need a stone for the pupils to stand on (the Pnyx), a ballot box, and a collection of black and white pebbles (or beans as a stand in!). TEACHER First, we need to establish who is able to take part in Athenian Democracy. Women and slaves were not allowed to do so, so they will not take part in the voting during this lesson. Decide who are going to be women and slaves and ask them to sit back down at their desk. Or, not to hurt anyone’s feelings, establish that the whole class is made up of free men (citizens)—so none are women or slaves. TEACHER First, we need to create the ruling council, called the Boule. This was a group of 500 citizens chosen to serve for a year using a lottery. The teacher chooses three citizens to become members of the Boule. They stand at the front of the classroom. TEACHER The members of our Boule have decided on three new laws for improving Athens. The rest of us make up the citizens’ assembly, known as the Ecclesia. Members of the Boule will read each new law out to us, and we will decide whether to approve them. Athenian citizens would stand on a stone called ‘the Pnyx’ to make their speeches. First member of the Boule stands on the Pnyx. Pupils can either devise their own laws, or read out the ones provided here. Voting in the Ecclesia often functioned by placing a white pebble in a ballot box for ‘yes’, and a black pebble for ‘no’. This can be acted out in the classroom, perhaps using dried white and black beans to act as pebbles. BOULE 1 ‘We are desperate to beat Sparta at the next Olympic games. Everyone has to do five hours of compulsory sports practice a week.’ Pupils vote with their pebbles, and the votes are counted. BOULE 2 ‘People need to spend more time worshipping our goddess Athena, so everyone has to go to the temple and pray four times a day.’ Pupils vote with their pebbles, and the votes are counted. BOULE 3 ‘To celebrate our recent victory in war against the Spartans, well will have a four day feast, with free wine and food for everybody.’ Pupils vote with their pebbles, and the votes are counted. TEACHER Another thing that the Greek citizens were allowed to do was to get rid of their own leaders, especially if they were a ‘tyrant’. If the citizens thought their leader was unfair, or nasty, or getting too big for their boots, the people could have them sent away from Athens for 10 years. This was called ‘ostracising’. So, we are going to imagine that I have been leading Athens for the last few years, and you as a class have the power to get rid of me and choose someone else. Have I been a ‘tyrant’ in leading you? Lets hold a vote. Pupils vote with their pebbles, and the votes are counted to see if the teacher is going to be ‘ostracised’. Lesson 3. Rough, Tough Sparta Sparta was famous for its warriors. This topic has gained a lot of attention in popular culture recently thanks to the film 300 (2006) and the graphic novel on which it was based. The secret to Sparta’s military success was an extremely tough child-rearing regime, where children were taken from their homes aged seven, and intensively trained to be a soldier until the age of 20. Weak children were simply killed at birth. Spartans were extremely disciplined, and disliked the luxury and hedonism of the Athenians. This attitude towards life is what gives us the word ‘spartan’ today. See pages 151 of What Your Year 3 Child Needs to Know. Learning Objective To understand why the Spartans were so tough. Core Knowledge The Spartans were famous for being the greatest warriors in Ancient Greece. Spartan boys were taken away from their mothers aged seven and trained to be soldiers. The training was extremely tough, but effective. The word ‘Spartan’ today is used to describe something that is very plain and basic, without much comfort – like the life of a Spartan soldier. Activities for Learning Learn about the regime of a Spartan boy training to be a soldier (shaved head, no shoes, violent punishments, little food). Pupils imagine that they are seven years old and have just started training. Write a diary entry or letter home about the experience. Read about the story of ‘The Brave Spartan Boy’. This could then be followed by comprehension questions, a diary entry from one of the boy’s classmates, or a classroom re-enactment (resource 3). This is a good videos about the Spartan army. Horrible Histories has a videos on Spartan schools, Spartan teachers, and Spartan teachers again, Spartan warriors, and a Spartan/Athenian wife swap. Related Vocabulary Sparta spartan Assessment Questions How were the Spartans different to the Athenians? What was life like as a Spartan child? Why did the boy in the story allow the fox to eat him to death? What is meant by the word ‘spartan’ today? Would you have liked to have been a Spartan? 3. The Brave Spartan Boy This famous story epitomises the Spartans’ unforgiving approach to rearing brave warriors. The extract is taken and adapted from The Story of the Greeks by H. A. Guerber. As strange as it sounds, the Spartans trained their boys to steal. They praised them when they succeeded in doing so without being found out, and punished them only when caught in the act. The reason for this strange custom was this: the Spartans were often engaged in war, so they had to depend entirely upon the provisions they could get on their way. If the Spartan soldiers had not been trained to steal, many of them would have starved during campaigns. Once a year all the boys were brought to the Temple of Diana, where their courage was tested by a severe flogging; and those who stood this whipping without a tear or moan were praised. The little Spartan boys were so eager to be thought brave, that it is said that some let themselves be flogged to death rather than complain. The bravery of one of these boys was so amazing that you will find it mentioned in nearly every Greek history you read. This little fellow had stolen a live fox which he planned to eat, and hid it underneath his shirt on his way to school. The imprisoned fox, hoping to escape, began to gnaw a hole in the boy's chest, and to tear his flesh with his sharp claws. If the boy had cried with pain, he would have been seen as weak. And if he had let the fox go, he would have been caught stealing. So, in spite of the pain, he just sat still. It was only when the boy fell lifeless to the floor that the teachers found the fox, and saw how cruelly he had torn the brave little boy to pieces. The boy died, having never said so much as a word. To strengthen their muscles, the boys were also carefully trained in gymnastics. They could handle weapons, throw heavy weights, wrestle, run with great speed, swim, jump, and ride, and were experts in all exercises which tended to make them strong, active, and well. They were also taught to treat old people, many of whom would have survived great and terrible wars, with total respect. Lesson 4. The Persian Wars Before the reign of Alexander the Great, the Persians Empire controlled much of Eastern Europe, Asia and North Africa. Persia was based in modern day Iran, and their forces conquered a number of Greek cities on the Ionian coast in modern day Turkey. In 499 BC, these Greek cities under Persian rule revolted, and the Athenians sent ships across the Aegean to support their Greek brothers. This angered the Persian King Darius, so he invaded mainland Greece in 492 BC. This led to a bitter thirty year war, during which Sparta and Athens united to fight their common enemy. It would result in a startling success for the Greeks. See pages 151-152 of What Your Year 3 Child Needs to Know. Learning Objective Core Knowledge Activities for Learning To know what the Persian Wars were, and what caused them. In the 5th Century BC, a civilisation known as the Persians controlled a powerful Empire. They were based in modern day Iran. Give the pupils a brief introduction of who the Persians were. A map of their Empire will show how close they were to Greek territory. Around 490 BC, the Persians invaded Greece under the command of King Darius, beginning a long war between the two civilisations. This led Athens and Sparta, who were once enemies, to unite in order to defeat the Persian army. Further examination of the Persian Empire could involve a study of the ‘cuneiform’ alphabet, and the famous Cyrus Cylinder. The British Museum has an excellent set of resources on this. This is a good website on the Ancient Persian capital of Persepolis, and this is a summary of the Persian Empire. This is a good image of a Greek hoplite fighting a Persian soldier. Label an image of a Greek Soldier (worksheet 4). Related Vocabulary Persia hoplite Assessment Questions Who invaded Greece in 490 BC? Why did the Persians invade Greece? Who were the Persians? What was unusual about the Athenians and the Spartans joining together? 4. The Greek Hoplite Phalanx 4. The Greek Hoplite (comp) A metal helmet. On top, it would have a crest made out of horse hair, designed to make the soldier look taller and fiercer. Leg protection called greaves. These were made of metal, like Ancient shin pads. A wealthy soldier would have bronze armour, often passed down through their family. Less wealthy soldiers would have layers of cloth glued together to make a tough, bendy material. The spear was the chief weapon of the hoplite, used to stab enemies from a long distance. It had a spike on both ends. A Greek soldier would have a round shield, made of metal and wood. This was known as the hoplon, which some believe is where the Hoplites gained their name. Phalanx The formation used by Greek Hoplites marching into battle. They would stand very close, protecting themselves with shields and poking their spears out in every direction... like a hedgehog. Lesson 5. Marathon and Thermopylae The Persian Wars involved two famous battles that are still remembered today. After the battle of Marathon, an Athenian named Pheidippides, whose job it was to run great distances to deliver messages, ran 26 miles to Athens to tell the city that the Persians had been defeated. He then dropped dead. Ever since, a race of 26 miles has been known as a marathon. The battle of Thermopylae was a last stand by the Spartan army against the Persians, guarding a narrow strip of land between the mountains and the sea. The Spartan code meant they all fought to the death, as can be seen in the modern day movie, 300 (2006). See pages 153-154 of What Your Year 3 Child Needs to Know. Learning Objective Core Knowledge Activities for Learning To know what the Persian Wars were, and why the battles of Marathon and Thermopile are still remembered today. Around 490 BC, a great civilisation known as the Persians invaded Greece, beginning a long war between the two civilisations. Read the stories of Marathon and Thermopylae. For either story (or both), pupils write a newspaper story explaining the event, and its significance for Ancient Greece (see worksheets 5 and 6). If you are feeling adventurous, pupils could even write an account in the form of a Homeric poem! This led Athens and Sparta, who were once enemies, to unite in order to defeat the Persian army. Two of the mot famous events of the Persian Wars were the Battle of Marathon, where Phidippides ran 26 miles to inform Athens of a Greek victory, and the Battle of Thermopylae, where 300 Spartans defended a narrow coastal path until every last one of them died. This is a good Horrible Histories video on Thermopylae, and another here. This and this are two other good videos on the battle. This is a good video on the Battle of Marathon, and this is the Horrible Histories take. Related Vocabulary Persia hoplite marathon Assessment Questions Who invaded Greece in 490 BC? Why did the Athenians and the Spartans join together? What happened after the Battle of Marathon? Why did the Spartans fight until the last death at Thermopylae? 5. Marathon Article THE ATHENIAN 6. Thermopylae Article THE SPARTAN