* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 2.3 Battle of Marathon Workbook and Internal Instructions

Spartan army wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek literature wikipedia , lookup

List of oracular statements from Delphi wikipedia , lookup

Corinthian War wikipedia , lookup

Peloponnesian War wikipedia , lookup

First Peloponnesian War wikipedia , lookup

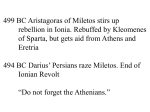

Ionian Revolt wikipedia , lookup

Second Persian invasion of Greece wikipedia , lookup