* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Appendix A: Calculations of transition rates in the outcome tree

Orthohantavirus wikipedia , lookup

Trichinosis wikipedia , lookup

Gastroenteritis wikipedia , lookup

Eradication of infectious diseases wikipedia , lookup

Schistosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Influenza A virus wikipedia , lookup

Hospital-acquired infection wikipedia , lookup

Yellow fever wikipedia , lookup

Typhoid fever wikipedia , lookup

Marburg virus disease wikipedia , lookup

1793 Philadelphia yellow fever epidemic wikipedia , lookup

Rocky Mountain spotted fever wikipedia , lookup

Leptospirosis wikipedia , lookup

Middle East respiratory syndrome wikipedia , lookup

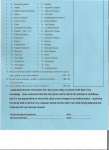

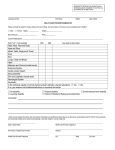

Coccidioidomycosis wikipedia , lookup

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Detailed information in the outcome trees Q fever Acute illness The Q fever acute illness is similar to the acute illness of influenza A(H1N1) pdm09, which is used as a proxy for Q fever acute illness, but is different in two aspects. First, those under 15 years of age are far less frequently symptomatic (12.5%) than cases that are over 15 years of age (40%) [1]. Secondly, the acute illness of Q fever has a higher percentage of pneumonia (61.5% [2]) than influenza A(H1N1) pdm09 (34.3% of hospitalized cases which are 2.2% of infected [3]) and hospitalization is also higher for Q fever (19.5%) [2] than A(H1N1) pdm09 (2.2%) [3]. Therefore the health outcome acute illness was divided into two health states, taking the difference in pneumonia (61.5% - (34.3%x2.2%) = 60.7%) to be a severe state and the remaining as mild heath state (1-60.7%=39.3%). The severe health state disability weight used was “P pneumonia – 2 weeks in the year” and the mild health state disability weight used was "P influenza – 2 weeks in the year" [4]. The result was age specific transition rate with mild and severe health states. Under 15 years of age had a lower symptomatic transition rate (12.5% [1]) and have typically a milder acute illness so only "P influenza – 2 weeks in the year" disability weight was used. Above 15 years of age the symptomatic transition parameter totaled the average from literature (40% of infected [5]) but divided into the two health states mild (39.3% of symptomatic (40% of infected)=15.7%) and severe (60.7% of symptomatic cases (40% of infected)=24.3%). The disability weights proxies used for mild (influenza) and severe (pneumonia) better represented the greater severity of the acute illness of Q fever versus influenza. The number of asymptomatic cases is equal to the number of infected minus the number of infected cases. Acute illness mortality is quantified by two studies of the Netherlands outbreak. One study on hospital mortality there were 9 patients of the 749 known hospitalizations that died [6] and knowing that roughly 20% of symptomatic patients are hospitalized [7], we can use 0.24%. A second parameter value comes from the number of deaths in 2009 as a total of the number of notified cases, 6 in 2357 notified cases, 0.25% [7]. Both were used in the model as a uniform distribution. Chronic Q fever The transition rate of symptomatic cases developing chronic Q fever (1.6%) [8] is derived from the Netherlands outbreak data and assumed to be the same for asymptomatic cases. This assumption is based upon contact with medical staff from the Jeroen Bosch Hospital, 'sHertogenbosch, the Netherlands who observed a limited number of chronic cases developing from asymptomatic infections and from the identification of an asymptomatic cases from the outbreak in Switzerland in 1983 developing chronic Q fever. The average duration of chronic Q fever before developing symptoms (2.75 years) [9] is included in the model as it reduces the life expectancy of the later health outcomes endocarditis and vascular infection. Post-infectious fatigue syndrome Fatigue is difficult to quantify and is a subjective outcome. Follow up studies after large outbreaks provide some information regarding duration and proportion retaining fatigue. One large outbreak cohort that is being followed from the United Kingdom used standard clinical criteria to quantify proportion of fatigue after 5 years [9] and after 10 years [10]. The first follow up reported a larger proportion of idiopathic chronic fatigue (ICF) in Q fever cases (42.3%) compared to matched controls (26%), a difference of 16.3%. At the ten year follow up point they matched cases on the presence of comorbidities and attending the hospital but still the Q fever cases had a higher proportion of ICF (21.6%) compared to controls (5.4%), a difference of 16.2%. The same study also looked at matched cases with comorbidities and/or attending a hospital but that had an even larger difference (71.4%) compared to controls (28.6%) and may overestimate the severity by incorporating comorbidity. Recent literature from the Netherlands outbreak on the proportion fatigue after 12 to 26 months is even higher (58.9% versus 12.3% in controls) than after five or ten years of follow up [11]. Interpreting severity of patients developing fatigue, two health states were used with similar disability weights but different durations. The mild health state (46.6%) is clinical cases that recover within 12 to 26 months and a severe health state (16.2%-16.3%) that are assumed to recover after 10 years. To prevent double counting the severe cases are removed from the mild health state (46.6% - mild health state). For post infectious fatigue syndrome, the health outcome "Major depression, mild episode" [4] was used as a proxy though it is likely to be an under-estimation given that the mode EQ-5D and mean EQ-5D for 85 patients with chronic fatigue syndrome is larger than the health outcome "Major depression, mild episode" [12]. Endocarditis The proportion of chronic Q fever cases that develop endocarditis from the literature gives us three values for a PERT distribution, a minimum (60%) [5], a maximum (75%) [13] and a most likely (73%) [14] value. A large proportion of endocarditis cases develop heart failure (67%) [5], so the proxy disability is taken from the WHO GBD, “congestive heart failure" [15]. The duration is reported to be less than one year (0.583) [16]. In the Netherlands we assumed that all cases would be treated and reduce the overall mortality (8%) [5] from the untreated proportion (100%) [14]. Vascular infection The proportion of chronic Q fever cases that develop vascular infection is not as common in most outbreaks. The available literature is limited and a single estimate was found (8%) [14]. For the remaining information estimates were taken from endocarditis health outcome including duration, disability and mortality. Influenza Acute illness The acute illness is assumed to be all infected cases in the model and asymptomatic cases are not included as they do not contribute to the total burden because they do not develop any long term sequelae. The disability weight is taken from the Stouthard et al., “Influenza burden per year” and represents the average, at population level, severity of a seasonal influenza infection (0.01 per year) [4]. This includes all complications of the acute illness and different severities. This includes, but is not limited to, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), sepsis and otitis media. It does not include permanent disabilities from these health states though, which need to be added. The mortality for influenza A(H1N1) pdm09 scenario 1 is taken from estimates by Wijngaard et al. that modeled mortality of A(H1N1) pdm09 [17]. Permanent disability due to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) After an acute infection a small percentage (0.038%) retain disability as a direct result of ARDS for the remainder of their life expectancy. To derive this proportion that develops permanent disability from ARDS the proportion of ARDS cases (63 of 1841 (3.4%) of hospitalized cases (2% of symptomatic cases) = 0.068%) [3], are multiplied by the proportion that retain permanent symptoms (56%) [18]. The disability weight proxy used is from Stouthard et al. “COPD” (0.17) [4]. Permanent disability due to otitis media (OM) After an acute influenza infection a small percentage (0.00000698%-0.0000088%) retain permanent disability due to otitis media (=deafness), for the remainder of their life expectancy. To derive this proportion that develops deafness, the proportion of cases developing otitis media (0.65%) [19] of cases attending a GP (17.9%-22.6% of symptomatic) [20] is multiplied by the proportion that retain permanent symptoms (0.006%) [15]. Permanent disability due to sepsis After an acute influenza infection a percent of the cases (0.026%) retain permanent disability after developing sepsis for the remainder of their life expectancy. To derive this proportion the proportion of hospitalized cases developing sepsis (1.58% (29/1841) of hospitalized (2% of symptomatic)) [3] is multiplied by the proportion retaining permanent disability (82%) [21]. The disability used is for sepsis long term sequelae (0.28) [21]. Sensitivity Analysis A sensitivity analysis was performed and estimates were obtained for the change relative to the total DALY estimate from baseline scenario for both diseases. The table shows lower bound estimates for a disability weight set to zero, and upper bound estimates for a disability weight set to 1, leaving all other parameters unchanged. In parentheses results are presented as percentages of the baseline estimates. For influenza the acute illness disability weight had the largest influence on the total DALY estimates. The disability weight for ARDS and sepsis contributed much less and long term sequelae due to otitis media contributed less than 1 DALY. For Q fever the post infectious fatigue syndrome severity changed the estimate the most followed by the severity of the acute illness health outcome. The two health outcomes for chronic Q fever (endocarditis and vascularitis) changed the DALY estimate by less than one percent in either direction. Supplementary Table S1 Sensitivity analysis of disability weights showing range of health state. Weight = 0 Weight = 1 20389 (83%) 23003 (94%) 24484 (100%) 22932 (94%) 429904 (1755%%) 31230 (128%) 24485 (100%) 28477 (116%) A(H1N1) pdm09 Acute influenza ARDS† long term disability Otitis media long term disability Sepsis long term disability Q fever Acute Q fever - mild 5751 (99%) Acute Q fever - severe 5089 (88%) Endocarditis 5752 (99%) Vascularitis 5793 (99%) PIFS* - mild 5118 (88%) PIFS* - severe 3145 (54%) *Post infectious fatigue syndrome †Acute respiratory distress syndrome 10333 (178%) 12166 (210%) 5958 (103%) 5815 (100%) 9970 (172%) 22088 (381%) References (1) Dupuis G, et al. An important outbreak of human Q fever in a Swiss Alpine valley. International journal of epidemiology 1987; 16(2): 282-287. (2) Dijkstra F, et al. The 2007-2010 Q fever epidemic in The Netherlands: characteristics of notified acute Q fever patients and the association with dairy goat farming. FEMS immunology and medical microbiology 2012; 64(1): 3-12. (3) van 't Klooster TM, et al. Surveillance of hospitalisations for 2009 pandemic influenza A(H1N1) in the Netherlands, 5 June - 31 December 2009. Euro surveillance : bulletin europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin 2010; 15(2). (4) Stouthard ME, et al. Disability Weights for Diseases in the Netherlands. Rotterdam, the Netherlands: Department of Public Health, Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands, 1997. (5) Maurin M, Raoult D. Q fever. Clinical microbiology reviews 1999; 12(4): 518-553. (6) Kampschreur LM, et al. Acute Q fever related in-hospital mortality in the Netherlands. The Netherlands journal of medicine 2010; 68(12): 408-413. (7) van der Hoek W, et al. Q fever in the Netherlands: an update on the epidemiology and control measures. Euro surveillance : bulletin europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin 2010; 15(12). (8) van der Hoek W, et al. Follow-up of 686 patients with acute Q fever and detection of chronic infection. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America 2011; 52(12): 1431-1436. (9) Ayres JG, et al. Post-infection fatigue syndrome following Q fever. QJM : monthly journal of the Association of Physicians 1998; 91(2): 105-123. (10) Wildman MJ, et al. Chronic fatigue following infection by Coxiella burnetii (Q fever): ten-year follow-up of the 1989 UK outbreak cohort. QJM : monthly journal of the Association of Physicians 2002; 95(8): 527-538. (11) Morroy G, et al. The health status of Q-fever patients after long-term follow-up. BMC infectious diseases 2011; 11: 97. (12) Myers C, Wilks D. Comparison of Euroqol EQ-5D and SF-36 in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation 1999; 8(1-2): 9-16. (13) Gami AS, et al. Q fever endocarditis in the United States. Mayo Clinic proceedings Mayo Clinic 2004; 79(2): 253-257. (14) Raoult D, et al. Q fever 1985-1998. Clinical and epidemiologic features of 1,383 infections. Medicine 2000; 79(2): 109-123. (15) Murray CJ, Lopez AD, Jamison DT. The global burden of disease in 1990: summary results, sensitivity analysis and future directions. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 1994; 72(3): 495-509. (16) Boyle B, Hone R. Q fever endocarditis revisited. Irish journal of medical science 1999; 168(1): 5354. (17) Wijngaard CC, et al. Comparing pandemic to seasonal influenza mortality: moderate impact overall but high mortality in young children. PloS one 2012; 7(2): e31197. (18) Mikkelsen ME, et al. Cognitive, mood and quality of life impairments in a select population of ARDS survivors. Respirology 2009; 14(1): 76-82. (19) Meier CR, et al. Population-based study on incidence, risk factors, clinical complications and drug utilisation associated with influenza in the United Kingdom. European journal of clinical microbiology & infectious diseases : official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology 2000; 19(11): 834-842. (20) Friesema IH, et al. Internet-based monitoring of influenza-like illness in the general population: experience of five influenza seasons in The Netherlands. Vaccine 2009; 27(45): 6353-6357. (21) Korosec Jagodic H, Jagodic K, Podbregar M. Long-term outcome and quality of life of patients treated in surgical intensive care: a comparison between sepsis and trauma. Crit Care 2006; 10(5): R134.