* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download ISSUES IN THE PLACEMENT OF ENCLITIC PERSONAL

Kannada grammar wikipedia , lookup

American Sign Language grammar wikipedia , lookup

Old English grammar wikipedia , lookup

Swedish grammar wikipedia , lookup

French grammar wikipedia , lookup

Navajo grammar wikipedia , lookup

Zulu grammar wikipedia , lookup

Portuguese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Lexical semantics wikipedia , lookup

Georgian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Malay grammar wikipedia , lookup

Chinese grammar wikipedia , lookup

English clause syntax wikipedia , lookup

Old Irish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Arabic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Sanskrit grammar wikipedia , lookup

Scottish Gaelic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Romanian nouns wikipedia , lookup

Yiddish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Serbo-Croatian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Modern Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Spanish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Esperanto grammar wikipedia , lookup

Turkish grammar wikipedia , lookup

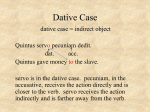

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Pipil grammar wikipedia , lookup

Latin syntax wikipedia , lookup