* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Large Intestine

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

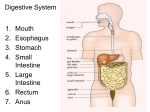

Large Intestine The large intestine is the terminal part of the gastrointestinal tract. The primary digestive function of this organ is to finish absorption, produce some vitamins, form feces, resorb water and eliminate feces from the body. The large intestine runs from the cecum, where it attches to the ileum, to the anus. It borders the small intestine on three sides. Despite its being around half as long as the small intestine – 4.9 feet versus 10 feet (1.5 – 3 meters) – it is called the large intestine because it is more than twice the diameter of the small intestine, 2.5 inches versus one inch (6 cm versus 2.5 cm). The large intestine is tethered to the posterior abdominal wall by the mesocolon, a double layer of peritoneal membrane. The large intestine is subdivided into four main regions: the cecum, the colon, the rectum, and the anus. The ileocecal valve, located at the opening between the ileum in the small intestine and the large intestine, controls the flow of chyme from the small to the large intestine. Large Intestine Anatomical Structures Like the small intestine, the mucosa of the large intestine has intestinal glands that contain both absorptive and goblet cells. However, there are several notable differences between the walls of the large and small intestines. For example, other than the anal canal, the mucosa of the colon is simple columnar epithelium. In addition, the wall of the large intestine has no circular folds, no villi, and essentially no enzymesecreting cells. This is because most nutrients are already absorbed before chyme enters the large intestine. The large intestinal wall does have thicker mucosa and deeper – and more abundant – glands that contain a vast number of goblet cells. These goblet cells secrete mucus that eases the movement of feces and protects the intestine from the effects of the acids and gases produced by enteric bacteria. Anatomical structures of the large intestine. This work by Cenveo is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 United States (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/us/). The stratified squamous epithelial mucosa of the anal canal joins with the skin around the anus. This mucosa varies considerably from that of the rest of the colon to accommodate the increased abrasion in this region. The anal canal's mucous membrane is organized in longitudinal folds called anal columns that house a grid of veins. Depressions between the anal columns, called anal sinuses, secrete mucus when feces crowd them. This facilitates defecation. The pectinate line is a horizontal, jagged band that runs alongside the inferior margins of the anal sinuses. The mucosa superior to this line is fairly insensitive to pain, while the area inferior to this line is very pain-sensitive. The difference in pain response is due to the fact that the superior region is innervated by visceral sensory fibers, and the inferior region is innervated by somatic sensory fibers. There are two superficial venous plexuses in the anal canal – one with the anus and the other with the anal columns. Inflammation and distension of these (hemorrhoidal) veins causes hemorrhoids, an itchy condition caused by the swelling of these vessels. Three features are unique to the large intestine: teniae coli, haustra, and epiploic appendages. The teniae coli are three bands of smooth muscle that make up the longitudinal muscle layer of the muscularis externa of the large intestine, except at its terminal end in the rectum. Tonic contractions of the teniae coli bunch up the colon into a succession of pouches called haustra, which are responsible for the wrinkled appearance of the colon. Attached to the teniae coli are small, fat-filled sacs of visceral peritoneum called epiploic appendages (omental appendices). These fatty pouches of peritoneum found in the serosa from the transverse colon through the sigmoid colon. Although the rectum and anal canal have no teniae coli or haustra, they do have well-developed layers of muscularis externa muscle that create the strong contractions needed for defecation. Large Intestine Gross Anatomy The first part of the large intestine is the cecum, a small sac-like region that is suspended inferior to the ileocecal valve. This cecum is about 2.4 inches long. The appendix or vermiform appendix (vermiform= “worm-shaped”, and appendix = “appendage”) is a winding, coiled tube that attaches to the cecum. This 2-7 cm (~3 inch) long appendix contains lymphoid tissue and plays an important role in immunity. Nevertheless, its twisted anatomy provides a haven for the accumulation and multiplication of enteric bacteria. The mesoappendix, the mesentery of the appendix, tethers it to the inferior part of the mesentery of the ileum. Gross anatomy of the large intestine. This work by Cenveo is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 United States (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/us/). The end of the cecum joins with the colon, a long tube with several distinct areas. The ascending colonruns up the right side of the abdomen. At the inferior surface of the liver, it takes a right-angle turn, forming the right colic (hepatic) flexure and becoming the transverse colon. The transverse colon runs across to the left side of the abdomen. It then bends sharply at a point immediately anterior to the spleen, forming theleft colic (splenic) flexure. As the descending colon, it runs down the left side of the posterior abdominal wall. After entering the pelvis inferiorly, it becomes the sshaped sigmoid colon, which extends medially to the midline. Most of the colon is between the peritoneal membrane and the body wall, except for the intraperitoneal transverse and sigmoid colons, which are tethered to the posterior abdominal wall by mesocolons. The sigmoid colon joins the rectum in the pelvis, near the third sacral vertebra. The rectum is the final 8 inches (20 cm) of the alimentary canal. It extends anterior to the sacrum and coccyx. Even though rectum is Latin for "straight," this structure has three lateral bends that create a trio of internal transverse folds called the rectal valves. These valves allow passing of gas (flatus) while preventing the simultaneous passage of feces. The last part of the large intestine is the anal canal, which is located in the perineum, completely outside the abdominopelvic cavity. This 1 inch (3 cm) long structure opens to the exterior of the body at the anus. The anal canal includes two sphincters. The involuntary internal anal sphincter is made of smooth muscle; the voluntary external anal sphincter is skeletal muscle. Except when defecating, these two sphincters are usually closed.