* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Understanding your child`s hearing tests

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

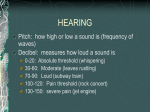

Understanding your child’s hearing tests A guide to the hearing and medical tests that are used to find out the type, level and cause of deafness Our vision is of a world without barriers for every deaf child. Contents 1 Introduction p4 2 The ear and how it works p5 3 Different types of deafness p6 4 Hearing tests p7 5 Audiograms p10 6 Hearing tests with hearing aids p14 7 Causes of permanent deafness p15 8 Medical tests used to help diagnose the cause of permanent deafness p16 9 Finding medical information on the internet p24 Understanding your Child’s Hearing Tests The National Deaf Children’s Society 3 1 Introduction This booklet explains the different types and levels of deafness and includes information on the variety of hearing tests that can be carried out to check a child’s hearing. It explains about the ear and how it works, different types of deafness, and audiograms. It also includes information on the different medical tests or investigations that are used to help diagnose the cause of permanent deafness. Students who are doing research about childhood deafness may also find this booklet useful. The guide is divided into different sections and each section has a different colour border to the pages. This can help you go straight to the information you need. See the Contents page for more information. Throughout this booklet the reader is directed to other NDCS publications on relevant topics for more information. We produce a wide range of free publications on childhood deafness. For more information or to order other publications, phone the NDCS Freephone Helpline on 0808 800 8880 or email [email protected]. Many publications are also available to download from our website at www.ndcs.org.uk. 4 The National Deaf Children’s Society Understanding your Child’s Hearing Tests 2 The ear and how it works The ear has two main functions. • It receives sound and converts it into signals that the brain can understand. • It helps us to balance. The two functions are closely related. The ear The ear is the first part of the hearing system. The pinna (the outside part of the ear) catches sound waves and directs them down the ear canal. The waves then cause the eardrum to vibrate. These vibrations are passed across the middle ear by three tiny bones: the malleus, incus and stapes (sometimes known as the hammer, anvil and stirrup, known together as the ossicles). The bones increase the strength of the vibrations before they pass through the oval window into the cochlea. The cochlea looks like a snail’s shell. It is filled with fluid and contains thousands of tiny sound-sensitive cells. These cells are known as hair cells. The vibrations entering the cochlea cause the fluid and hair cells to move, much like the movement of seaweed on the seabed when waves pass over it. As the hair cells move, they create a small electrical charge or signal. The auditory nerve carries these signals to the brain where they are understood as sound. For an ear to work fully and allow us to pick up sound, all of these parts must work well. Deafness happens when one or more parts of the system are not working effectively. Balance The brain uses information from the eyes (what we see), our body (what we feel) and the inner ear to balance. The semicircular canals in the inner ear are three tubes, filled with liquid and movement-sensitive hair cells. As we move, the fluid moves. This creates signals that are sent to the brain about balance. For more information about balance read our factsheet Balance and Balance Disorders. Understanding your Child’s Hearing Tests The National Deaf Children’s Society 5 3 Different types of deafness Conductive deafness is when sound cannot pass efficiently through the outer and middle ear to the cochlea and auditory nerve. The most common type of conductive deafness in children is caused by ‘glue ear’. Glue ear (or otitis media) affects about one in five children at any time. Glue ear is a build-up of fluid in the middle ear. For most children, the glue ear clears up by itself and does not need any treatment. For some children with long-term or severe glue ear, hearing aids may be provided; or the child may need surgery to insert grommets into the eardrums. Grommets are tiny plastic tubes which are inserted into the eardrum. They allow air to circulate in the middle ear and help to prevent fluid from building up. For more information read our leaflet Glue Ear. Sensori-neural (or nerve) deafness is when there is a fault in the inner ear (most often because the hair cells in the cochlea are not working properly) or auditory (hearing) nerve. Sensori-neural deafness is permanent. Children who have a sensori-neural deafness can also have a conductive deafness such as glue ear. This is known as mixed deafness. 6 The National Deaf Children’s Society Understanding your Child’s Hearing Tests 4 Hearing tests There are a variety of tests that can be used to find out how much hearing your child has. The tests used will depend on your child’s age and stage of development. It is possible to test the hearing of all children from birth onwards. Screening tests are normally done first to see if it is likely that there is a hearing loss and the child needs to be referred to an audiologist. The audiologist will then perform more detailed tests to build up an accurate picture of your child’s hearing. You can ask your audiologist for a copy of your child’s test results. You may like to keep them in your own file at home or take them with you when you visit the audiology department or ear, nose and throat doctor. Objective hearing tests Otoacoustic emissions (OAE) The otoacoustic emission test is commonly used as part of the screening tests carried out on babies shortly after birth. It works on the principle that a healthy cochlea will produce a faint response when stimulated with sound. A small earpiece (containing a speaker and microphone) is placed in the child’s ear. A clicking sound is played and if the cochlea is working properly, the earpiece will pick up the response. This is recorded on a computer and tells the tester whether the child needs to be referred for further tests. A poor response to an OAE test does not necessarily mean that a child is deaf. Background noise, an unsettled baby, or fluid in the ear from the birth can all make it difficult to record the tiny response. Auditory brainstem response (ABR) The audiologist will place three small sensors and a set of headphones on the child’s head. For an accurate result, the child must be very still and quiet throughout the test. In young babies the test can be carried out while they are sleeping. In slightly older children, a light sedative or an anaesthetic may be offered. This test measures whether sound is being sent from the cochlea and through the auditory nerve to the brain. It can be used as a screening test (Automated Auditory Brainstem Response – AABR – where the computer judges whether a response is present at quiet levels of sound) or as a more detailed test where different levels of sound are used and the audiologist interprets the results to find the quietest level of sound being picked up by the hearing nerves. Understanding your Child’s Hearing Tests The National Deaf Children’s Society 7 In very young children or children who are not developed enough to have behavioural hearing tests, the results of the ABR test can be used to accurately fit hearing aids if these are necessary. In older children this test may be used to confirm the results of their behavioural test. Behavioural tests As your child grows older, their audiologist will get more information about your child’s hearing through behavioural tests. These tests use toys and play as part of the assessment and involve your child listening for a variety of sounds as part of a game. Visual response audiometry (VRA) Visual response audiometry is suitable for children from six months to about two-anda-half years. Using a machine called an audiometer, sounds of different frequencies and loudness are played through speakers. When the child hears the sound, they will turn their head and a visual ‘reward’ is activated, such as a toy lighting up or a puppet. The test can check the full range of hearing but does not give specific information about each ear. If your audiologist feels it is important to get information about each ear individually, this test can be done with small earphones. Pure tone audiometry From about the age of three, children are actively involved in testing by using a technique known as conditioning. Younger children are shown how to move a toy (for example, putting a peg into a board) each time they hear a sound. Older children are asked to respond to sounds by saying yes or pressing a button. The sounds come through headphones, earphones placed inside the child’s ear, or sometimes through a speaker (when the test is known as soundfield audiometry). Bone-conduction All of the tests above are described as testing using air conduction (that is, sounds passing through the ear canal and middle ear before reaching the cochlea). ABR, VRA and PTA can also be tested using bone-conduction. A small vibrating device is placed behind the child’s ear. This passes sound directly to the inner ear through the bones in the head. This technique is useful for identifying whether a hearing loss is conductive or sensori-neural. 8 The National Deaf Children’s Society Understanding your Child’s Hearing Tests Speech discrimination tests Speech discrimination tests check the child’s ability to hear words at different listening levels. The tester asks the child to identify toys or pictures, or to copy words spoken by themselves or from a recording. From this the tester can assess the quietest level at which the child can correctly identify the words used. This test can also be used to assess lipreading and signing skills. Tympanometry Tympanometry is not a test of hearing; it is used to check how well the moving parts of the middle ear are working. A small earpiece is held gently in the ear canal. A pump causes the pressure of the air in the ear canal to change. The eardrum should move freely in and out with the change in pressure. The earpiece measures this by checking the sound reflected by the eardrum. If the eardrum is not moving freely, there is likely to be some fluid or another problem with the middle ear. This build-up of fluid is usually glue ear (or otitis media). Glue ear can cause temporary conductive deafness. For more information read our leaflet Glue Ear. The line for a child without glue ear is curved. The line for a child with glue ear is flat. Hearing tests and children with additional or complex needs The tests used will depend on your child’s age as well as their stage of development. It should be possible to test the hearing of any child, whatever their stage of development, but it is more likely that several different tests will need to be done to get a clear picture of any hearing difficulty. Objective tests (such as OAE and ABR) do not need a child to respond to a sound in order to get a result. However, the child needs to be very still and quiet throughout the test, which may mean they need a light sedative or an anaesthetic. Some children with additional needs may have to be tested using techniques that are normally used with younger children. If your local audiology service is not confident about testing your child, you can ask to be referred to another centre with more experience of testing children with complex needs. Understanding your Child’s Hearing Tests The National Deaf Children’s Society 9 5 Audiograms Some of your child’s test results will be written on a chart like the one below, known as an audiogram. It shows you how loud a sound has to be, and at what frequency, before your child can hear it. Your child’s test results may be plotted on one chart (as below) or two charts, side by side, for each ear separately. Crosses always indicate results for the left ear, and circles for the right ear. Your child may be deaf in one ear (unilateral deafness) or both ears (bilateral deafness). If your child is deaf in both ears, the deafness may be similar in both ears (symmetrical deafness) or different in each ear (asymmetrical deafness). Your child’s deafness may also be described as high frequency or low frequency, measured in hertz (Hz). We commonly think of frequency as the pitch of a sound. A piano keyboard runs from low-pitch on the left to high-pitch sounds on the right and the audiogram is the same. There are different levels of deafness. These can be described as a decibel (dB) hearing level (how loud a sound has to be for your child to hear it) or described using terms such as ‘mild’, ‘moderate’, ‘severe’ or ‘profound’. The very quietest sounds are at the top of the chart, getting louder as you look down the page. Visual representation of the loudness and pitch of a range of everyday sounds Frequency in Hertz (Hz) Low 125 -10 Levels of deafness: High PITCH 250 500 1000 0 2000 4000 F 10 F L O R R Y Mild deafness 21 - 40 dB L O R R Y Moderate deafness 41 - 70 dB BAND Severe deafness 71 - 95 dB B U Z Z Hearing level in decibels (dB) 20 F f sth F zv L O R R Y p hg ch sh B U Z Z 30 F 8000 L O R R Y BAND B U Z Z j 40 F BAND mdb n ng el u B U Z Z L O R R Y k B U Z Z BAND i oa r BAND 50 L O R R Y B U Z Z BAND 60 F L O R R Y 70 B U Z Z BAND 80 F F 90 L O R R Y F F L O R R Y F F F F Profound deafness 95+ dB 100 B U Z Z F B U F L O R R Y L O R R Y Z Z BAND L O R R Y BAND Loud sounds L O R R Y L O R R Y 110 L O R R Y B B L O R R Y U U Z Z Z Z L O R R Y B BAND BAND U Z Z B U B Z 120 Z U B U Z BAND Z B Z Z U Z BAND Z BAND BAND B U Z BAND Z BAND 10 The National Deaf Children’s Society Understanding your Child’s Hearing Tests On the audiogram on page 10 there are pictures of common sounds that give us an idea of loudness and frequency. There are also speech sounds drawn on the chart, and you can see that all the sounds of speech cover a range of frequencies. Try saying some of the speech sounds out loud while looking at the chart. The sounds m, b, and d are on the left-hand side and part way down the chart, meaning that they are lower frequency and slightly louder than say f, s, and th, which are higher in frequency and much quieter. So it is important to be able to hear sounds at a quiet level, across the frequency range, to be able to hear all the sounds of speech clearly. Ask your child’s audiologist to explain your child’s hearing test results to you and how they will affect your child’s ability to hear speech. Some examples of different audiogram results Typical range of hearing This audiogram shows the level and range for a person with typical hearing levels. Frequency in Hertz (Hz) 125 -10 Results above the line represent typical hearing levels 250 500 1000 2000 4000 0 X Left Ear 10 Right Ear 8000 X X X X X X Hearing level in decibels (dB) 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 110 120 Understanding your Child’s Hearing Tests The National Deaf Children’s Society 11 Frequency in Hertz (Hz) 250 500 1000 ] 2000 4000 ] X X X X X X ] Bone conduction test Sensori-neural deafness in the right ear This audiogram shows a sensori-neural deafness in 125 -10 the right ear. You can see that both the air- and 0 bone-conduction tests 10 give similar results. 8000 ] ] Hearing level in decibels (dB) Conductive deafness in the left ear This audiogram shows a typical conductive deafness 125 in a child’s left ear. There -10 are two lines – one shows 0 the result of air-conduction tests (with headphones or 10 earphones in the ears) 20 marked by crosses, and the other shows bone30 conduction results marked 40 by square brackets ([). The bone-conduction test 50 shows that the inner ear is 60 receiving the signal clearly, but the air-conduction test 70 shows that the sound is 80 being blocked by fluid or another obstruction in the 90 outer or middle ear. This 100 child may have a temporary conductive deafness as a 110 result of glue ear or a 120 permanent conductive deafness. X Air conduction test Frequency in Hertz (Hz) 250 500 1000 2000 [ [ 4000 8000 Hearing level in decibels (dB) 20 30 40 50 [ [ 60 70 80 90 100 110 120 12 The National Deaf Children’s Society [ Bone conduction test Air conduction test Understanding your Child’s Hearing Tests Mixed deafness in the right ear Frequency in Hertz (Hz) 125 -10 250 500 1000 2000 4000 8000 0 10 20 Hearing level in decibels (dB) This last audiogram gives an example of mixed deafness in the right ear. Both the bone-conduction and air-conduction tests show that there is a hearing loss. Because the results are very different, this child has more than one cause of deafness. [ [ 30 40 [ [ 50 60 70 80 90 100 110 120 Understanding your Child’s Hearing Tests [ Bone conduction test Air conduction test The National Deaf Children’s Society 13 6 Hearing tests with hearing aids If your child does have a hearing loss, they may be fitted with hearing aids. VRA, soundfield audiometry and speech testing can all be used while wearing hearing aids, and the results provide some information about what your child can hear with them. When these results are written down, they are called ‘aided responses’. ‘Real ear measurements’ will also be used to make sure the hearing aid’s settings are as close as possible to your child’s hearing loss. Real ear measurements (REM) Your child’s hearing aids will be programmed for each child’s hearing loss. Two children with identical hearing losses and identical hearing aids will have slightly different prescriptions. This is because the size of each child’s ear canal will vary, and this can alter the signal (or frequency response) coming from the hearing aid. The audiologist will use a ‘probe tube microphone’ to take measurements in your child’s ear canal to make sure that the hearing aid is set correctly. (This type of testing is not suitable for children who use bone-conductor hearing aids.) Other methods of assessing the benefit of hearing aids Your audiologist or teacher of the deaf will go through a questionnaire or checklist with you and your child to find out how well your child listens in different situations with the hearing aid (for example, how they are at identifying different sounds at home, working in groups at school, or using the phone). If your child is very young, your observations using the Common Monitoring Protocol in your Early Support Family Pack may be used. The results of these can be used to fine-tune the settings of the hearing aids if necessary. 14 The National Deaf Children’s Society Understanding your Child’s Hearing Tests 7 Causes of permanent deafness There are many reasons why a child can be born deaf or become deaf early in life. It is not always possible to identify the reason, but you may be offered further tests to try and establish the cause of your child’s deafness. Causes before birth (pre-natal causes) Around half the deaf children born in the UK every year are deaf because of a genetic (inherited) reason. Deafness can be passed down in families, even though there appears to be no family history of deafness. For about 70% of these deaf children, no other problems will occur. For the other 30%, the gene involved may cause other disabilities or health problems. Deafness can also be caused by complications during pregnancy. Infections such as rubella, cytomegalovirus (CMV), toxoplasmosis and herpes can cause a child to be born deaf. There are also a range of medicines, known as ototoxic drugs, which can damage a baby’s hearing system before birth. Causes in early childhood (post-natal causes) Being born prematurely can increase the risk of a child being deaf or becoming deaf. Premature babies are often more prone to infections that can cause deafness. Severe jaundice or a lack of oxygen at some point can also cause deafness. Infections during early childhood, such as meningitis, measles and mumps, can be responsible for a child becoming deaf. Occasionally, a head injury or exposure to loud noise can damage the hearing system. For more information about the tests used to find out the cause of deafness, read section 8. Understanding your Child’s Hearing Tests The National Deaf Children’s Society 15 8 Medical tests used to help diagnose the cause of permanent deafness This section tells you about the range of medical tests that can be carried out to try to find the cause of your child’s deafness. The process to find out why a child is deaf is sometimes called an ‘aetiological investigation’. The tests listed in this section can find the reason for a child’s deafness in 40% to 50% of cases. For the other 50% to 60% of cases it is not possible to find out why a child is deaf. If it is not possible to find out the cause of your child’s hearing loss, it may be helpful for you to know what did not cause it. 16 The National Deaf Children’s Society Understanding your Child’s Hearing Tests Doctors may sometimes suggest tests on other parts of your child’s body, like the kidneys or heart, to help identify the cause or rule out certain conditions that can be associated with deafness. Deafness can be part of a ‘syndrome’ (syndrome is a medical term meaning a collection of symptoms or signs that commonly appear together). It is important to know about any associated medical conditions so you can consider appropriate treatment or ways of managing the deafness or condition. However, these conditions are relatively rare in deaf children and extremely rare in the population as a whole. As with many services provided by the NHS, for some tests you may be asked to give your written permission first. Throughout this section we use the following terms: • ‘Your doctor’ to mean the doctor in charge of your child’s audiological care. This may be an audiological physician, ENT specialist, or community paediatrician in audiology. • ‘Your family’ includes your child’s grandparents on both sides. We would like to thank the members of the Aetiological Investigations Group for the valuable advice they gave to help us produce the information in this section. What happens when you see the doctor? The doctor will take details of your child’s medical history. This will include questions about the pregnancy, including any medication that was taken during the pregnancy and the mother’s health before, during, and after the birth. The doctor will ask you about your child’s immunisations (routine baby jabs). In toddlers and older children, the doctor will ask about your child’s development (including speech, language and milestones such as when your child was sitting, walking and so on). The doctor may also ask about whether your child has: • had meningitis, mumps, measles or other illnesses • been exposed to loud noises • taken any prescribed medication • suffered any head injuries • had any ear infections • had sight problems • had balance problems. All of these factors are important when investigating the cause of deafness. The doctor will also ask about the hearing of other family members, on both sides of the family. Understanding your Child’s Hearing Tests The National Deaf Children’s Society 17 Physical examination The doctor will look at your child’s head and face area and may also take some measurements. The doctor will also look at your child’s neck, skin, nails, arms, legs, chest, abdomen (tummy), eyes, mouth, palate (roof of the mouth) and ears. They are looking for any minor differences or signs (for example, tiny holes in the skin known as ‘pits’), that may help to diagnose the cause of the deafness. The doctor will assess your child’s development in relation to the expected ages and stages (see your baby’s Personal Child Health Record – the Red Book – for further information on this). The doctor may ask close family members to have a hearing test, known as an audiogram. Imaging Imaging is a general term covering different ways of looking at parts inside the body (such as bones or major organs) and how they are working. The doctor uses an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan or a CT (computerised tomography) scan to look at the structure of the ear and hearing nerve as well as other parts of the body that may be associated with the deafness. Both types of scan are commonly used with children who have deafness. An MRI scan will show soft tissues including the brain and hearing nerve. It will show if the hearing nerve has developed normally. MRI scans use magnets and radio waves to produce detailed pictures of the inside of the body. There are no known side effects associated with this type of scan. An MRI scan can be carried out on a child from birth, but you should be offered a choice of when the scan is done. If it is important for your child to have the scan, the doctor will explain this to you. 18 The National Deaf Children’s Society Understanding your Child’s Hearing Tests A CT scan will show the bony parts of the ear including the ‘ossicles’ (the three tiny bones in the middle ear) and the ‘cochlea’ (the inner ear). A CT scan will show if the bony parts have developed normally. A CT scan involves exposing your child to radiation in the form of X-rays. The level of radiation used is kept as low as possible to prevent damage to body cells, and the amount of radiation your child is exposed to depends on the number of images taken. It is generally accepted that there is little risk to health from one scan, but with repeated tests there is a risk that the radiation may damage body cells. There is only a risk if your child has a high number of x-rays or scans. The earlier in life your child is exposed to radiation, the greater the risk. You and the doctor may prefer to wait until your child is a little older. Your child’s doctor will discuss this with you and answer any questions you may have. Your child will need to be absolutely still for the time it takes to do a CT or MRI scan. Very young babies may be able to have these scans while they are asleep. Each hospital will have its own procedure, and your doctor will explain this to you. Generally, children aged over three months will normally be given something to help them sleep. This may be a light sedative or a short general anaesthetic. For children aged over two, you may be offered a stronger sedative or a general anaesthetic. Although modern anaesthetics are extremely safe, there are small risks associated with having an anaesthetic and your doctor should explain these to you. The risks of having an anaesthetic reduce as the child gets older. Usually, children over the age of five can lie still for the scan without needing a sedative or anaesthetic. A further type of scan that may sometimes be used is a renal ultrasound. This is a scan that uses sound waves to create images of the kidneys. It is similar to the scans used during pregnancy. It is only likely to be used to rule out a rare syndrome or if there is a family history of kidney problems. There are no risks associated with this type of scan. Your doctor may recommend that one or more of the above scans are done at an early stage, for example, if: • your child has had meningitis • your child is being referred to be assessed for a cochlear implant • the deafness is getting worse or changing over time • there are characteristic features that may suggest your child’s deafness could be part of a ‘syndrome’. In these examples, your doctor will need to look closely at the structure of the cochlea (inner ear) and hearing nerve to be able to give you advice on possible management or treatment options. Understanding your Child’s Hearing Tests The National Deaf Children’s Society 19 Electrocardiography (ECG) An ECG is a recording of the rhythm and electrical activity of the heart. There is a very rare syndrome linking severe and profound hearing loss to a heart problem. If this heart problem is detected it can be treated. Depending on your child’s and your family’s medical history, your doctor may advise an ECG for a small number of children with severe to profound deafness to help rule out this condition. There are no risks associated with having this test. Blood and urine tests Depending on your child’s and your family’s medical history, the doctor may ask for one or more routine blood and urine tests. These tests can help doctors to identify the cause of the deafness. An example of a blood or urine test your child may be offered is an infection screen. An infection screen is used to look for certain infections that sometimes result in deafness. Some of these tests will give useful results only if they are carried out in the weeks or months shortly after your child’s birth. When the child is older, an infection screen may give a negative result and rule out an infection being the cause of the deafness. However, a positive result later in life may not give useful information as your doctor could not prove that the infection was present at birth and so caused the deafness. There are several infections that can cause deafness in babies if the mother contracts them when pregnant. The most common infection causing babies to be born with deafness is CMV (cytomegalovirus). CMV is very common in the general population and does not normally cause any illness. However, it can affect the baby if the mother catches it while pregnant. CMV infection in an unborn baby is called ‘congenital CMV’. (‘Congenital’ means from birth.) About one baby in every 200 is born with CMV and some of these babies can be affected by it. Congenital CMV can cause deafness or, very occasionally, it can affect a child’s development. Congenital CMV causes about 10% to 20% of deafness in children in the UK. Doctors can test for CMV in the first few weeks after birth, or for older children look for signs of the CMV infection in the 20 The National Deaf Children’s Society Understanding your Child’s Hearing Tests heel-prick blood test cards which are stored after birth. Deafness following infection can sometimes get worse over time. If a young baby is found to have the CMV infection, it may be possible to give treatment that may prevent the deafness from increasing. For more information you may like to read our leaflet Congenital Cytomegalovirus and Deafness. Less common infections that can cause deafness include rubella (German measles), toxoplasma and syphilis. Your doctor will be able to give you more information about these infections. All the blood tests are usually done using one blood sample. Ophthalmology (eye test) All children learn from what they see and hear around them. Children who are deaf rely on their eyesight even more than other children do. Up to 40% of children with sensori-neural deafness also have an eye problem. This may simply mean the child will need to wear glasses when they are older, but an eye test can also help to diagnose a syndrome associated with deafness. As babies can’t tell us what they can see, a developmental assessment of the eye is done to make sure the eyes are healthy. Sometimes special eye tests are used. Your opthamologist (eye doctor) will discuss this with you if necessary. It is recommended that all children diagnosed with deafness are referred for an eye test and have regular eye tests throughout their childhood. For more information about eye tests you may like to read our leaflet Vision Care for your Deaf Child. Understanding your Child’s Hearing Tests The National Deaf Children’s Society 21 Genetic counselling Just as children inherit features such as hair colour or eye colour from their parents, sometimes deafness is inherited. If your child’s deafness could have a genetic cause, you should be given the chance to discuss this with a trained genetics counsellor. Genetic counselling gives families information about: • the cause of a range of inherited conditions • how an inherited condition might affect the child and family in the future • how likely you are to have another child with the same condition. Some families find it helpful to know whether the deafness and any other medical condition were inherited. Other families prefer to wait until their children are grown up and able to decide for themselves. For more information you may like to read our leaflet Genetic Counselling: Information for families. Genetic testing You may be offered a genetic test. This will involve your child, and possibly other family members, having a blood test. The blood sample will be used to look for the gene or genes known to be involved with deafness. Not all the genes related to deafness have been identified and for most there is not yet a routine test. This means that even if the deafness is inherited, it may not be possible to confirm this with a genetic test at the moment. About 50% of children with permanent deafness have a genetic cause. In about 30% of children with a genetic deafness, the deafness is part of a syndrome. Again, some of these syndromes can be confirmed with a genetic test, but many cannot. Some children have a rare genetic deafness that can get worse if they are given certain medications. It is possible to have a genetic test to identify whether they have this gene. If they do, then this information will help inform you and your doctor if, in the future, your child needs treatment. Your doctor may recommend that this test is done at an early stage depending on your child’s history. Your doctor may refer you to a clinical geneticist or a genetic counsellor. Alternatively, they may discuss genetic testing with you themselves. Individual health authorities decide whether to offer routine genetic testing through the audiology or ENT department. Some areas offer genetic testing through this route only if it would provide a direct benefit to the child being tested. For example, if the child has an inherited medical condition it may be of direct benefit to have a genetic test. This is because the results may help to identify treatments that should be made available to the child. Your doctor will discuss the options available in your area with you. If you want to ask more about genetic testing, you can ask to be referred to your local clinical genetics service and your doctor will discuss with you if this is appropriate. For more information on the genetics of deafness you may like to read our leaflet Genetic Counselling: Information for families. 22 The National Deaf Children’s Society Understanding your Child’s Hearing Tests What next? Some or all of the tests in this section will be offered to your child, not necessarily in the order given here. Your doctor will give you more information which will help you decide whether you want your child to have the available tests and the best time for the tests to be carried out. Test results that may offer immediate benefit to a baby are best done at an early stage, for example when the infection screen is carried out. Some tests (for example, some routine genetic testing) will not offer an immediate or direct benefit to a baby and may be delayed until a later stage. Your doctor will tell you if particular tests should be done (for example, if your doctor suspects that your child’s deafness is part of a syndrome). You and your doctor can use this information when planning how to manage the hearing loss and any associated condition in the future. Most of the tests are not urgent. It is important that you feel comfortable with your child having them. Discuss any worries with your doctor. Understanding your Child’s Hearing Tests The National Deaf Children’s Society 23 9 Finding medical information on the internet Thanks to Contact a Family for letting us reproduce this information from their leaflet Finding Medical Information on the Internet. You can find the full consumer guidelines at www.northumbria.ac.uk/sd/academic/ceis/re/isrc/themes/ibarea/ju/ The internet can be a very useful source of information for families, but the number and types of websites can cause confusion. The aim of this section is to help you decide whether a website provides relevant, high quality information. What to look for on support group websites. Support groups’ websites allow you to get in touch with other people. Consider the following. •Can you find clear contact details for the organisation that set up the website? •If there are email lists, bulletin boards and chat rooms, you are likely to be in touch with people who are genuine. But remember, some may have extreme views. •Check that your personal information will be kept secure and not shared with others. •See if your personal details are being recorded when you visit the website. •Can you contact the website manager to report technical problems and provide comments about the site? The NDCS has an online discussion group called Parent Place, where parents and other family members share information and practical advice. How reliable is the medical information? Consider the following: •Check the author’s name, job title, workplace, and any formal or professional qualifications. •Check the date the information was put on the site. Medical information can become out of date very quickly. •Is the information aimed at getting you to buy something? •Does the information acknowledge that specific conditions affect people in different ways, ranging from mild to severe? •Check whether the information is based on a person’s own experiences. How the condition affects your child may differ from other people’s experiences. •Does the information sound extreme? 24 The National Deaf Children’s Society Understanding your Child’s Hearing Tests Who is the website for? •Websites are aimed at different groups of people (for example, professionals, academics, members of the public). Detailed pieces of academic research can be confusing, and may not be helpful. Think about who the website is aimed at and how useful the information will be. Who produced the website? Websites can be set up by anybody, from respected organisations and experts to people with extreme views and companies trying to sell you something. Consider the following: •Look for the name, address and contact details of the organisation. •Does the organisation have a registered charity number (if relevant)? •What are the aims and purpose of the organisation? •Check the names and qualifications of any professionals contributing to the website. Is there an Advisory Panel or Review Group? •Websites should state clearly if the information is based on people’s personal experiences. •Websites sponsored by commercial organisations may be biased towards certain treatments or products. Adverts that appear on a website might also reflect this. Websites from outside the UK can be useful, but may refer to medicines using different names from those used here, or ones not licensed for use in this country. There may be different medical practice and treatments in other countries. Understanding your Child’s Hearing Tests The National Deaf Children’s Society 25 Notes 26 The National Deaf Children’s Society Understanding your Child’s Hearing Tests NDCS provides the following services through our membership scheme. Registration is simple, fast and free to parents and carers of deaf children and professionals working with them. Contact the Freephone Helpline (see below) or register through www.ndcs.org.uk • A Freephone Helpline 0808 800 8880 (voice and text) offering clear, balanced information on many issues relating to childhood deafness, including schooling and communication options. • A range of publications for parents and professionals on areas such as audiology, parenting and financial support. • A website at www.ndcs.org.uk with regularly updated information on all aspects of childhood deafness and access to all NDCS publications. • A team of family officers who provide information and local support for families of deaf children across the UK. • Specialist information, advice and support (including representation at hearings if needed) from one of our appeals advisers in relation to the following types of tribunal appeals: education (including disability discrimination, special educational needs (SEN) and, in Scotland, Additional Support for Learning (ASL)); and benefits. • An audiologist and technology team to provide information about deafness and equipment that may help deaf children. • Technology Test Drive – an equipment loan service that enables deaf children to try out equipment at home or school. • Family weekends and special events for families of deaf children. • Sports, arts and outdoor activities for deaf children and young people. • A quarterly magazine and regular email updates. • An online forum for parents and carers to share their experiences at www.ndcs.org.uk/parentplace. • A website for deaf children and young people to get information, share their experiences and have fun at www.buzz.org.uk. NDCS is the leading charity dedicated to creating a world without barriers for deaf children and young people. NDCS Freephone Helpline: 0808 800 8880 (voice and text) [email protected] JR0371 www.ndcs.org.uk Published by the National Deaf Children’s Society 15 Dufferin Street, London EC1Y 8UR ISBN 978-1-907814-01-3 Tel: 020 7490 8656 (voice and text) Fax: 020 7251 5020 NDCS is a registered charity in England and Wales no. 1016532 and in Scotland no. SC040779 © NDCS REPRINT November 2013 This publication can be requested in large print, in Braille and on audio CD.