* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download After the cultural turn, a return to the moral economy[1]

Survey

Document related concepts

Ragnar Nurkse's balanced growth theory wikipedia , lookup

Ethnoscience wikipedia , lookup

Popular culture studies wikipedia , lookup

Cultural ecology wikipedia , lookup

Development economics wikipedia , lookup

Development theory wikipedia , lookup

Postdevelopment theory wikipedia , lookup

Embedded liberalism wikipedia , lookup

Cultural psychology wikipedia , lookup

Economic anthropology wikipedia , lookup

Steady-state economy wikipedia , lookup

Anthropology of development wikipedia , lookup

Intercultural competence wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

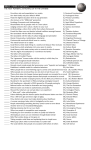

BALIHAR SANGHERA After the cultural turn, a return to the moral economy1 The recent ‘cultural turn’ in the social sciences has led some writers to rethink the relationship between culture and economy. 2 The term ‘cultural economy’ tries to outline the ways in which the economic is inseparable from the cultural.3 The term refers to how cultural meanings and identities are embedded in the economic life. We cannot explain how economic practices are coordinated without understanding the actors’ interpretations and the meanings behind their actions. This presentation of culture and economy is an improvement on previous approaches that privileged the economy over culture, or reduced cultural practices to economic structures, or treated the two as separate and unconnected entities. But this recent depiction of culture and economy has a fundamental limit: there is little interest in moralpolitical values. To be sure, the prioritisation of aesthetic values over moral-political values in recent studies of the cultural economy reflects the one-sidedness and a narrow conception of cultures.4 This 1 2 3 4 I am grateful to my students and colleagues at Novosibirsk State University and Irkutsk State University in the Russian Federation, and the National University of Mongolia, Ulaan-Baator, for their helpful comments on some of the issues covered in this article. See for example the collection of writings edited by Larry Ray and Andrew Sayer, Culture and Economy after the Cultural Turn (London: Sage Publications, 1999). For an example of this approach see Paul Du Gay and Mike Pryke, eds., Cultural Economy: Cultural Analysis and Commercial Life, (London: Sage Publications, 2002). See Andrew Sayer, ‘Valuing Culture and Economy’ (posted on the Web at comp.lancs.ac.uk/sociology/soc023as.html, 1999); see also, Andrew Sayer, ‘Equality and Moral Economy’, (posted on the Web at comp.lancs.ac.uk/sociology/soc059as.html, 2000). 2 Balihar Sanghera article aims to correct this imbalance, and will suggest the ways in which the economy is embedded with moral values. Moral values concern how society should be organised, how others should be treated, our responsibilities to others, relationships with other species and the environment, and so on.5 In the first section, I will discuss the cultural economy approach, comparing it to more traditional approaches to culture and economy in advanced industrialised societies. In the next section, I shall provide a critique of this approach, highlighting its failure to deliver what it promises. Finally, a critique implies an alternative standpoint: the moral economy perspective will be shown to offer a more critical and normative understanding and explanation of the contemporary issues. The cultural economy approach Increasingly contemporary writers argue that the economy has become ‘culturally stylised’, or aestheticised.6 By this, they mean two things. First, this tendency refers to how more cultural goods (music, literature, fashion, films, sport, etc.) are produced or mediated through the market. In particular, many writers (for example Adorno and Horkheimer or more recently Baudrillard and Featherstone) have spelled out the implications of this process by examining mass culture, mass consumption and fragmented identities. A second meaning refers to how production systems have become sensitive to the meanings people attach to work, and to the efficacy of reconstructing meaning at work. In particular, the writers on post-Fordism and corporate culture often claim that conflictual 5 6 As discussed by William Booth, ‘On the idea of the moral economy’, in American Political Science Review, vol. 88, no. 3 (1994), pp. 653-667. See for instance Paul Du Gay, ed, Production of Culture/Cultures of Production (London: Sage Publications and Open University, 1997); Du Gay and Pryke, eds., Cultural Economy; Scott Lash and John Urry, Economies of Signs and Space (London: Sage Publications, 1993). After the cultural 3 labour relations and arm’s length market relations have given way to a high degree of trust and embedded, negotiated processes of coordinating economic practices. It is also claimed that by constructing either an enterprise culture or a total quality management system in the organisation, economic relations and practices can become more personally fulfilling and enriching for workers, and productive and profitable for the company. Table 1 highlights the key ways in which the cultural economy approach differs from economic liberalism and Marxist political economy. To be sure, the cultural economy framework has several distinct advantages over them (see Table 2). There are many positive effects of the cultural turn in the social sciences – both in taking culture, meaning and subjectivity more seriously, and in escaping from reductionist accounts of culture as a mere reflection of the material situation. This cultural turn coincides with the decline of socialism, and the diversification of the concerns of radical politics beyond economic questions of distribution towards cultural questions of recognition and identities.7 Research into the forms of domination and division that go beyond those deriving from capital and class was long overdue. A critique of the cultural economy perspective While acknowledging the importance of ‘culture’ within the economy, and appreciating how cultural economy is an improvement on economic liberalism and traditional political economy, there are particular difficulties within the cultural economy perspective. The first weakness is that the cultural economy model uncritically accepts ‘the market’ as a central mechanism in the economy. The cultural economy model treats the public as the market, 7 For a helpful discussion of the nature and the implications of the cultural turn, see Larry Ray and Andrew Sayer, eds., Culture and Economy after the Cultural Turn (London: Sage Publications, 1999). 4 Balihar Sanghera and the people as consumers. Yet we are not offered a political and moral critique of the market’s place in the economy – i.e., the effects of economic markets on human values and social practices. As we shall see later, the market mechanism, while appealing to individual needs, actually poses a threat to the individuality of those who inhabit the cultural economy terrain. The second weakness is that the model seems to suggest that a society that creates more cultural meanings and lifestyles is better than one in which there are less. So we are invited to assess the effects of globalisation by whether it adds to or subtracts from cultural diversity and aesthetics. Again, when considering fashion, we are supposed to ask whether it enables consumers to be active in creating their own identities. Yet trying to maximise meanings, lifestyles and aesthetics could be seen as morally suspect and unacceptable. For example, women in pornographic magazines can be described in terms of their beauty, youthfulness and attractiveness, but such images may be interpreted as degrading and dehumanising to women. Similarly welldressed fascists preaching messages of ethnic intolerance and hatred may well be seen as morally repugnant. The third weakness concerns the methodology, which highlights the importance of contexts, identities and contingency. This literature also details how markets and organisations are socially constructed; that is, particular identities are not essential or fixed, but changing. While it contains within itself a much-needed corrective to traditional political economy, this methodological stance deliberately fails to identify any essential and necessary social relations and social tendencies, and shies away from any detailed abstract analyses (i.e., one-sidedness). Inevitably, such an anti-essentialist and firmly constructivist methodology produces studies that are more prone to mistakenly attributing causality, confusing is with ought, and failing to make critical interventions.8 Let us examine some of the weaknesses in more detail. Market operations have implications for the individual’s identity, autonomy 8 For a more detailed discussion of these issues, see Andrew Sayer, ‘System, lifeworld and gender: associational versus counterfactual thinking’, in Sociology, vol. 34, no. 3 (2000), pp. 707-725. After the cultural 5 and desire for recognition. I will argue that cultural economy’s dependence on market systems undermines its project of autonomy for the individual, who desires recognition. We can identify three internal weaknesses of the cultural economy approach. Identity: according to the ‘cultural economy’ framework, identity revolves around leisure and centres on looks, images and consumption. It celebrates the market as it develops an autonomous character: as consumers, we can choose our own taste, and as entrepreneurs, we are responsible for our own success. The cultural economy highlights the playfulness of choosing our own identities at will from an array of market choices and opportunities.9 Yet the market can undermine identity and personal character, because identity under market conditions tends to be unstable and subject to change: market incentives to act in particular ways are constantly changing. Individuals are no longer engaged in life projects, or fail to make long-term commitments, and so abandon deeper responsibilities (single issue protest movements for example). Autonomy requires settled commitments, values, life projects and responsibilities that define what it is to have a character. Under changing market conditions and incentives, such long-term commitments and deep responsibilities are discouraged. Authority and autonomy: autonomous people accept only that which they are able to affirm according to their own reasoning or experiences. Such a person appears most readily in the guise of the sovereign consumer and the individual entrepreneur, particularly in what has been called the ‘enterprise culture’.10 The cultural economy appeals to autonomous people who can use their own powers of judgement and decision to formulate projects and to make commitments: the individual does not depend on the authority of others. Authoritative standards in the product market (such as safety and quality standards for consumer goods) and labour markets (such 9 10 For more on the enterprising self and the consuming self, see Paul Du Gay, Consumption and Identity at Work (London: Sage Publications, 1996). See Nikolas Rose, ‘Governing the enterprising self’, in The Values of the Enterprise Culture, edited by Paul Heelas and Paul Morris (London: Routledge, 1992). 6 Balihar Sanghera as workers’ rights) are seen as incompatible with autonomy and freedom, and tend towards paternalism, elitism and a lack of individual responsibility. Here the sovereign self merges with the autonomous and responsible self. However, as John O’Neill in his book The Market: Ethics, Knowledge and Politics rightly argues, we can distinguish between social authority (authority conferred on a person, such as political and religious figures, on the basis of their institutional or social position), and epistemological authority (authority and knowledge arrived at through impersonal standards, dialogue and practical reasoning). While we can be suspicious of the former, the latter is both necessary and desirable in making reasonable judgements and decisions. Without authority, we are prone to making mistakes (e.g. ignoring the advice of our own doctor not to smoke and drink) that undermine our desire for autonomy. Recognition: recognition is required to confirm our self-worth as beings with powers of rationality and the capacity to stand above and shape particular desires. Yet recognition of worth and praise (or compliments) counts only from those other individuals whom we recognise to have worth. Recognition requires professional and trade associations, academic and scientific communities and craft guilds, whose recognition we respect as worth having. Recognition requires other people located in non-market institutions, and because of this we must reject an individualised market economy. The cultural economy approach describes heavy consumption of cultural goods as a desire for recognition, though it would be more accurate to say a desire to be noticed. However, recognition takes place entirely at the level of appearances – we buy goods that are ‘cool’ and aesthetically pleasing to the senses. Here, there is no distance between recognition for looking good and for being good.11 Individuals do not seek recognition to confirm their independent worth or gain praise for worthy acts, but for the recognition of their appearance, in pursuit of love of praise. Appearance is fought over by 11 On this point see Alistar MacIntyre, After Virtue: A study in moral theory (London: Duckworth, 1985). See also Russell Keat, Cultural Goods and the Limits of the Market (Basingstoke: Macmillan Press, 2000). After the cultural 7 producers and consumers usually in the form of better or worse aesthetic tastes. Indeed, the idea of recognition of worth, dependent on professional or trade association, is absent. In short, the market rewards self-esteem rather than self-respect. The moral economy approach Without an adequate moral framework to evaluate the cultural and economic, the cultural economy approach can be dismissed as simply a version of neo-liberalism, naively celebrating the false gods of market choices, individual autonomy, and value-neutrality.12 We shall evaluate the cultural economy approach by examining the moral economy approach (see Table 3), suggesting reasons why the latter is preferable to the former. A crucial feature of many of the goals or goods associated with culture is that they are primarily internal, i.e., intrinsic. For example, a certain kind of music might be valued, but this value is not accorded merely in order to achieve some external goal, but because the kind of music is valued in itself. By contrast, economic activities and processes involve a primarily instrumental orientation; they are ultimately a means to an end, satisfying external goals to do with provisioning. The meaningful aspects of activities, artefacts and relationships, whose value is primarily internal, are combined in various ways with instrumental activities directed towards the external goal of reproduction of social life. The internal association of the cultural and the economic implies that it is wrong to think of the relation between them as simply external. A question like ‘How has the economy been influenced by culture?’ implies that there was first a pristine economy which somehow later fell under the influence of 12 For a useful survey of the ethical and social limits of the market economy, see John O’Neill, The Market: Ethics, Knowledge and Politics, (London: Routledge, 1998). 8 Balihar Sanghera culture, when of course economic activities have always been culturally embedded. In the moral economy approach, cultures include values among their signifying practices. These may involve judgements and sentiments regarding utility, aesthetics and moral-political matters. Contemporary writers of the cultural economy approach are overly preoccupied with aesthetic values, as evident in their focus on style and taste; indeed the definition of their object of study refers to the ‘stylisation of life’.13 Yet there is less interest in moral-political values. For Sen, Habermas, Polanyi and other writers on the moral economy, central to the question of the relationship between culture and economy is that of the nature and role of moral-political values and the potential moralising and identity-neutral effects of the market.14 The tendency of neo-liberal theorists and cultural economy writers to reduce culture to the stylisation of life and private preferences is complicit in the de-moralisation of culture and derationalisation of moral-political values. There is a tendency to ignore moral influences on social life, usually by interpreting them either as merely subjective and emotive, or in instrumental, power-based terms, ‘strategies of distinction’, to use Bourdieu’s term.15 In order to counter these tendencies, a new version of the concept of moral economy is required that highlights the ways in which all economic activities – 13 14 15 See for example Scott Lash and John Urry, Economies of Signs and Space (London: Sage Publications, 1993); Stuart Hall, ed., Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices (London: Sage Publications and Open University, 1997); Paul Du Gay, ed., Production of Culture/Cultures of Production. See Georg Simmel, Conflict and the Web of Group-Affiliation (New York: Free Press, 1955); Albert Hirschman, ‘Rival Interpretations of the Market Society: Civilising, Destructive, or Feeble?’, in Journal of Economic Literature, vol. 20, no. 4 (1982), pp. 1463–1484; Andrew Sayer, Radical Political Economy: A Critique (Oxford: Blackwell, 1995); Sayer, ‘Equality and Moral Economy’. Pierre Bourdieu, ‘La production de la croyance: contribution à une économie des biens symboliques’ [The production of belief: contribution to an economy of symbolic goods], in Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, no. 13, February (1977), pp. 4–43. After the cultural 9 both formal and informal, or domestic – are influenced by norms and conventions, including ethical principles. The moral economy embodies norms, conventions, tacit understanding, and ‘constitutive rules’ regarding the responsibilities and rights of individuals and institutions with respect to others and regarding the nature and qualities of goods, services and environment. These norms, conventions and constitutive rules shape both the formal and informal, including household economies. It is worth noting that while these norms, conventions and constitutive rules may be considered as part of a moral order, they are invariably influenced by networks of power and considerations of costs.16 The emergence of the market society has de-moralised society in another way. As Habermas and Sen point out, the development of economic systems (institutions characterised by formal rationality such as markets and bureaucracy) has turned questions of validity into questions of behaviour, and turned ethical and political questions into engineering and technical ones. The questions of purpose and ethics have become secondary to questions of fitness for purpose and techniques.17 Indeed, liberals and contemporary social theorists have usually depicted actors and institutions as merely instruments, generating wealth and producing a social order.18 In other words, the sphere characterised by formal rationality and impersonality dominates the sphere characterised by deliberation and negotiation. As Sayer argues, as people lost control over their economic lives (i.e., ‘vagaries of the market’), became alienated at work and from others, and came to have close economic relations with distant unknown others (i.e., advanced division of labour), the competitive laws of global economy tended to reduce the normative standpoints on moral economy, correspondingly making philosophical discourse on ethics appear irrelevant.19 However, we need to return to the questions of 16 17 18 19 See Robert Salais and Michael Storper, ‘The four “worlds” of contemporary industry’, in Cambridge Journal of Economics, vol. 16, no. 2 (1992), pp. 169– 193. See Russell Keat, Cultural Goods and the Limits of the Market. For a useful survey of modern social theories of the market society, see Don Slater and Fran Tonkiss, Market Society (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2001). Andrew Sayer, ‘Valuing Culture and Economy’. 10 Balihar Sanghera validity, ethics and purpose, otherwise we collude with the dominance of economic systems over the cultural sphere, condemning ourselves to the senseless truck, trade and barter mentality and to market fatalism. Sayer raises some issues of moral economy, validity, ethics and purpose that fundamentally question the nature of advanced industrialised societies.20 What are our responsibilities towards children, the elderly, the disabled and infirm, to distant others and future generations, and to the environment? How should we discharge our responsibilities to others? By paying taxes to fund transfer payments? Through direct unpaid labour? By paying others to do the work? How should these responsibilities be allocated between men and women, or between people of different incomes and wealth? To what extent should people be reliant on wages for their income? How far should income be subject to the anarchy of the market, or to the self-adjusting market? What things should not be commodified? Of course, our answers and practices to these and other questions require an informed and practice-based dialogue and engagement, in which the participants have equal opportunity to discuss, act and decide. In any one generation, practices and decisions will inevitably vary according to the historical, political and cultural circumstances. However, this does not mean that we should accept moral relativism, which is usually a disguised form of power. Rather, all practices and decisions require an identification with and a recognition of fundamental and transnational values such as equality, freedom from oppression and poverty, autonomy, respect for cultural difference, and so on. Concluding remarks: three dimensions of the moral economy 20 See Sayer, ‘Valuing Culture and Economy’; ‘Equality and Moral Economy’. After the cultural 11 To strengthen the explanatory and critical claims of the moral economy approach, I will conclude by suggesting the different dimensions along which the economy is morally embedded: they are institutional, explanatory and normative. Institutional: the market society cannot be characterised as socially disembedded since markets require the construction of property rights, of contracts and their enforcement, and so on that enable them to operate. To depict the economy as a self-regulating market is to misconstrue the emergence and the development of the market society.21 To be sure, the moral reconstruction of the economy suggests that the provisioning of human beings is embedded in relations of justice. For example, members of families give gifts to one another based on their norms of deference and of reciprocal obligations between parents and children, and their religious beliefs. Members of a political community will adapt relations of distribution and of production to the norms and values of the community. For instance, a community that recognises the inequalities among its members will restructure economic relations differently to one in which freedom and liberty are highly valued. Explanatory: as Booth notes, economics as the science of wealth must be guided by the question of wealth’s purpose: wealth is an instrumental good, and it has a purpose external to itself, and in light of which its worth is judged.22 This claim, then, makes economics an ethical inquiry about the nature of the good life and about the place of the economy in relation to it. Consequently, economic science is incomplete if it fails to embed its studies of the economy in a wider cultural context. Economics must be centrally informed by the question of the good to which the economy serves. Significantly, this shifts us away from the liberal inquiry of rights, neutrality and selfownership, towards a normative study grounded in questions like ‘To what purpose?’ and ‘What good is served?’ In addition, according to Adam Smith and the Scottish Enlightenment thinkers, markets have a ‘civilising effect’: reducing 21 22 See Slater and Tonkiss, Market Society. Booth, ‘On the idea of the moral economy’, in American Political Science Review, pp. 653-667. 12 Balihar Sanghera the power of the sovereign, and encouraging individuals and nations to be industrious and attentive to one another’s needs and to cultivate a reputation for fair dealing so as not to damage their creditworthiness and market position.23 Similarly, Simmel argues that commerce is a powerful socialising and moralising agent that brings many non-material improvements to society, even though a bit of double-dealing may have to be accepted into the bargain.24 Normative: the historical transition from non-economic and feudal relations to market (and visibly economic) relations yields a new form of moral embeddedness, in which labour and land are freed from their status-determined, non-consensual location in the social hierarchy. Indeed, as Walzer notes, the market sphere is one sphere of justice, in which equality and autonomy are accorded primacy, operating in a pluralistic field of different spheres with other principles of justice.25 Given the plurality of spheres of justice, society must limit the effects of the market by regulating it in various ways according to other values and norms. 23 24 25 This is pointed out by in Albert Hirschman, ‘Rival Interpretations of the Market Society: Civilising, Destructive, or Feeble?’, in Journal of Economic Literature, pp. 1463-1484. Simmel, Conflict and the Web of Group-Affiliation. Michael Walzer, Spheres of Justice (New York, Basic Books, 1983). 13 After the cultural Economic liberalism Basic focus Marxist Political economy Cultural economy Private economic interests and market freedom Main figures/movements Power relations economic life Culture and identity Adam Smith Neo-classical economics Public choice theory Hayek Key concepts Marx Labour process theory Class theory Gramsci Weber, Foucault Politics of recognition Social constructionism Baudrillard Individual sovereignty Self-interest Rationality Self-regulating market Spontaneous order Private property rights Private morality Small governments Methodology Mode of production Social relations of production and exchange Property rights Capitalism Commodification and decommodification Exploitation Modes of representation Discursive strategies of resistance and struggle Consumption and identity Interpretations Cultural symbolism Norms and conventions Individualism, atomism empiricism and idealism Essentialism, dialectics, abstractions, materialism and critical realism Social constructionism, contingency, discourse analysis and narratives in Table 1 Comparison of the main approaches to economy and culture26 26 Adapted from Robert Holton, Economy and Society (London: Routledge, 1992). 14 Balihar Sanghera Weaknesses of economic liberalism and Marxist political economy Improvised interest-based view of economic action and the motivation of economic participants Strengths of cultural economy Inability to explain the normative basis of economic and social cohesion; indeed reduces this to interest and/or power Provides an analysis of the interpretative and symbolic basis of economic and social order, including tacit rules as well as explicit modes of political regulation Inability to demonstrate that economic interest is sufficient to generate changes in cultural practices as well as in economic and social life Emphasises the order-transforming elements of culture at the personal, organisational, national and global levels Provides a deep understanding of the issues of meaning and motivation (i.e., the connections between meaning and economic action) Table 2 Strengths of the cultural economy approach over traditional approaches27 27 Adapted from Holton, Economy and Society. After the cultural 15 Cultural Economy Deals with recognition and signifying practices Basic Focus Moral Economy Deals with recognition and signifying practices Stylisation of life; aesthetic values; status, prestigious and positional goods, e.g. fashions, advertising, mass consumption, corporate culture, and identity at work Moral implications, choice and regulation; rights and responsibilities; virtues and social relations, e.g. public service broadcasting, antipornography, business ethics, and moral obligations Questions of validity, asking what economic activities are for, e.g. citizenship, public sphere as democratic forum, civil society, and Nordic democratic welfare states Life projects, long term commitments and deep responsibilities Distinction between social and epistemological authority Love of praiseworthy acts, desire to be worthy of recognition Questions of behaviour, adapting to economic systems, e.g. enterprising self, consumer, public as market place, and neo-liberal US and UK neo-liberal workforce states Playfulness of identities Sceptical of any authority Love of display, praise and promotion, desire to be noticed Table 3 Comparison between moral economy and cultural economy approaches 16 Balihar Sanghera Bibliography Booth, William, ‘On the idea of the moral economy’, in American Political Science Review, vol. 88, no. 3 (1994), pp. 653-667. Bourdieu, Pierre, ‘La production de la croyance: contribution à une économie des biens symboliques’ [The production of belief: contribution to an economy of symbolic goods], in Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, no. 13, February (1977), pp. 443. Du Gay, Paul, Consumption and Identity at Work (London: Sage Publications, 1996). Du Gay, Paul, ed, Production of Culture/Cultures of Production (London: Sage Publications and Open University, 1997). Du Gay, Paul and Mike Pryke, eds., Cultural Economy: cultural analysis and commercial life (London: Sage Publications, 2002). Hall, Stuart, ed., Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices (London: Sage Publications and Open University, 1997). Hirschman, Albert, ‘Rival Interpretations of the Market Society: Civilising, Destructive, or Feeble?’, in Journal of Economic Literature, vol. 20, no. 4 (1982), pp. 1463-1484. Holton, Robert, Economy and Society (London: Routledge, 1992). Keat, Russell, Cultural Goods and the Limits of the Market (Basingstoke: Macmillan Press, 2000). Lash, Scott and John Urry, Economies of Signs and Space (London: Sage Publications, 1993). MacIntyre, Alistar, After Virtue: A study in moral theory (London: Duckworth, 1985). O’Neill, John, The Market: Ethics, Knowledge and Politics (London: Routledge, 1998). Ray, Larry and Andrew Sayer, eds., Culture and Economy after the Cultural Turn (London: Sage Publications, 1999). Rose, Nikolas, ‘Governing the enterprising self’, in The Values of the Enterprise Culture, eds. Paul Heelas and Paul Morris (London: Routledge, 1992). After the cultural 17 Salais, Robert and Michael Storper, ‘The four “worlds” of contemporary industry’, in Cambridge Journal of Economics, vol. 16, no. 2 (1992), pp. 169-193. Sayer, Andrew, Radical Political Economy: A Critique (Oxford: Blackwell, 1995). Sayer, Andrew, ‘Valuing Culture and Economy’ (1999) published by the Department of Sociology, Lancaster University at: http://www.comp.lancs.ac.uk/sociology/soc023as.html Sayer, Andrew, ‘Equality and Moral Economy’ (2000a) published by the Department of Sociology, Lancaster University at: http://www.comp.lancs.ac.uk/sociology/soc059as.html Sayer, Andrew, ‘System, lifeworld and gender: associational versus counterfactual thinking’, in Sociology, vol. 34, no. 3, (2000b), pp. 707-725. Simmel, Georg, Conflict and the Web of Group-Affiliation (New York: Free Press, 1955). Slater, Don and Fran Tonkiss, Market Society (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2001). Walzer, Michael, Spheres of Justice (New York, Basic Books, 1983).