* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Ancient Greece: Fundamental Transition from

Regions of ancient Greece wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek architecture wikipedia , lookup

History of science in classical antiquity wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek warfare wikipedia , lookup

Greek contributions to Islamic world wikipedia , lookup

Economic history of Greece and the Greek world wikipedia , lookup

Greek Revival architecture wikipedia , lookup

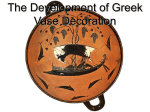

Ancient Greek literature wikipedia , lookup

Science in the Arts Ancient Greece: Fundamental Transition from Convention-Based to Observation-Based Art Marek H. Dominiczak* The realistic representation of the human figure is one of the hallmarks of ancient Greek art. It reflects the increasing importance of observation in that culture. In painting and sculpture the transition from pure decoration to naturalist representation began in the Archaic period (600 – 480 BC), and continued through the Pre-Classical (480 – 450 BC) and Classical (450 – 400 BC) periods of Greek history. Artistic creativity was at least in part a result of underlying societal and political change. The independent city-states (poleis) emerged in Greece in the eighth century BC. In the sixth century, the Greek world bordered the Persian Empire, which extended from Thrace on the Greek mainland, through the Eastern shores of the Mediterranean, to Egypt and North Africa and to India in the East. There were many trade routes in the Eastern Mediterranean that linked the Greek cities with the Levant, Egypt, and the Asia Minor. In addition, emigration from the homeland was part of the Greek way of life, and by the sixth century Greek settlements were established in southern France, Italy, Egypt, and North Africa, as well as on the shores of the Black Sea. Although the migrant Greeks retained their language and rituals, they were exposed to local cultures. The major conflict between the Greeks and Persians erupted around 500 BC when some Greek cities in Asia Minor rebelled against Persian domination. Subsequently, the Persians twice invaded the Greek mainland. They were eventually defeated in 480 BC in a sea battle at Salamis. Athens, the city-state that contributed most to the victory, achieved prominence in the Greek world and was the main focus of Greek culture throughout the Classical period (1 ). Thus there was access to diverse art styles. Ancient Egypt had a long tradition of painting and monumental sculpture. Egyptian painting conventions, such as representation of persons using profile faces and fron- College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK. * Address correspondence to the author at: Department of Biochemistry, Gartnavel General Hospital, Glasgow G12 0YN, UK. Fax ⫹44141-211-3452; e-mail [email protected]. Received July 31, 2014; accepted August 13, 2014. © 2014 American Association for Clinical Chemistry tal eye shape, were adopted by the Greeks. The more organic, curvilinear forms probably came from the Levant and Persia. Interestingly, Levantine and Persian influences were hardly highlighted—if not suppressed— by the early historians of classical art, whose mantra was the entirely independent evolution of the Greek artistic style. We know about Greek painters from the written sources because no freestanding paintings survived. A major source of our knowledge comes from the images on pottery. The early vases produced in the so-called Geometric period (900 –700 BC) had purely decorative patterns. This gradually changed to painting of organic, mostly marine forms. In 700 – 640 BC the style was strongly influenced by Egyptian painting, and this became known as the Orientalizing period. Later still, the scope of vase decoration broadened to scenes of mythology and everyday life. Two main types of vases are the black-figure vases (700 – 480 BC), invented in Corinth, and the red-figure vases invented in Athens around 530 BC (2, 3 ). In the black-figure pottery, human and animal figures were shown as black silhouettes with pale incised lines. The background was plain and there were occasional red and white painted details. The figures on these vases are characteristically 2-dimensional. Although they show little anatomical detail, there are attempts to show movement and draw dynamic poses. Some vases contain a series of drawings with complex narratives, such as those on the François Vase created by the painter Kleitias and potter Ergotimos. The vase contains several bands (friezes) of decorative patterns, animal figures, and mythological scenes (4 ). In the red-figure vases the figures were red and the background black. A brush was used instead of a graver; this allowed the artists to vary the thickness of paint and thus present volumes more realistically. There are also more anatomical details, and the stances became anatomically correct. Drawing techniques get more sophisticated with foreshortening and hints of depth in the scenes. There are increasingly complex folds and patterns on clothing, seen clearly in the work of the painter Makron (5 ). A parallel transition from convention to naturalism can be observed in Archaic sculpture, which Clinical Chemistry 60:11 (2014) 1461 Science in the Arts Acropolis in 1886 (8 ). It is one of the technically most advanced pieces. There are traces of paint on the face, and traces of dress pattern and delicately sculpted dress folds. She wears a peplos, a woolen garment worn over the shoulders. The predominant view is that the pottery painters were inspired by the free-standing painting and sculpture. Boardman points, for instance, to the similarities between relief sculpture found in the Siphnian Treasury in Delphi just before 525 BC and paintings on some red-figure vases (9 ). Interestingly, this increasingly naturalistic approach in the arts loosely parallels the emergence of philosophy in the Ionian Greek cities on the shores of Asia Minor, and thus the reworking of the world view from myth oriented toward observation based (10 ). Science and experiment could not have emerged without this transition. Author Contributions: All authors confirmed they have contributed to the intellectual content of this paper and have met the following 3 requirements: (a) significant contributions to the conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; (b) drafting or revising the article for intellectual content; and (c) final approval of the published article. Authors’ Disclosures or Potential Conflicts of Interest: No authors declared any potential conflicts of interest. Acknowledgments: My thanks to Jacky Gardiner for her excellent secretarial assistance. Fig. 1. Kore no. 679, c. 550 to c. 480 BC (marble), Greek School. Acropolis Museum, Athens, Greece. Bridgeman Images. ©Reproduced with permission. evolved from small figurines, and reliefs created on the pediments of temples, to large freestanding pieces. These sculptures, at the beginning, also showed strong Egyptian influences. The characteristic works are the male (Greek kouroi, singular kouros, meaning “young man”) and female (korai, singular kore, meaning “maiden”) votive figures, which also served as grave markers (6 ). Kouroi and korai were made in marble, bronze, wood, and other materials. Most of them were life size and showed a uniformly vertical stance. The male figures were always nude and the female ones were clothed. The first kouroi appeared in the seventh century BC. Similarly to pottery painting, there is a gradual emergence of anatomical detail, such as the musculature of the early New York Kouros (7 ). The kore shown in Fig. 1 is known as the Peplos Kore. It was created around 520 BC and was found on the Athenian 1462 Clinical Chemistry 60:11 (2014) References 1. Forrest G. Greece: the history of the Archaic Period. In: Boardman J, Griffin J, Murray O, Eds. The Oxford history of Greece and the Hellenistic world. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1988. 2. Boardman J. Athenian Black Figure vases. London: Thames and Hudson; 1997. 3. Boardman J. Athenian Red Figure vases. The Archaic period. London: Thames and Hudson; 1997. 4. Cartwright M. Francois Vase. Ancient history encyclopedia. http://www. ancient.eu.com/Francois_Vase/ (Accessed July 2014). 5. Makron (vase painter). http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Makron_(vase_painter) (Accessed July 2014). 6. Lapatin KDS. Kouros/kore. In: Brigstocke H, ed. The Oxford companion to Western art. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001. p 398. 7. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Heilbrunn timeline of art history. Statue of a kouros (youth), ca. 590 –580 B.C. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/worksof-art/32.11.1 (Accessed July 2014). 8. Johnston A. Pre-classical Greece. In: Boardman J, ed. The Oxford history of classical art. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1997. p 11– 82. 9. The Museum of the Goddess Athena. Siphnian Treasury East Frieze. Delphi Museum. http://www.goddess-athena.org/Museum/Sculptures/Group/Siphnian_ Treasury_East_Frieze_x.htm (Accessed July 2014). 10. Thales of Miletus (c. 620 BCE - c. 546 BCE). Internet encyclopedia of philosophy. http://www.iep.utm.edu/Thales/ (Accessed July 2014; reaccessed October 2014). DOI: 10.1373/clinchem.2013.218354