* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

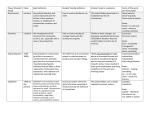

Download Paradigms of Explanation and Varieties of Capitalism

World-systems theory wikipedia , lookup

Steady-state economy wikipedia , lookup

Economic anthropology wikipedia , lookup

Postdevelopment theory wikipedia , lookup

Depleted community wikipedia , lookup

Reproduction (economics) wikipedia , lookup

Embedded liberalism wikipedia , lookup

Non-simultaneity wikipedia , lookup

Transformation in economics wikipedia , lookup

Rostow's stages of growth wikipedia , lookup

Political economy in anthropology wikipedia , lookup

Environmental determinism wikipedia , lookup

Development theory wikipedia , lookup