* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download - Sacramento - California State University

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

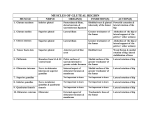

OUTPATIENT REHABILITATION FOR A PATIENT WITH SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS CONSISTENT WITH ILIOTIBIAL BAND SYNDROME A Doctoral Project A Comprehensive Case Analysis Presented to the faculty of the Department of Physical Therapy California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHYSICAL THERAPY by TomMa SUMMER 2016 © 2015 TomMa ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 11 OUTPATIENT REHABILITATION FOR A PATIENT WITH SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS CONSISTENT WITH ILIOTIBIAL BAND SYNDROME A Doctoral Project by TomMa , First Reader DPT, FAAOMPT , Second Reader Clare Lewis, PT, PsyD, MPH, MTC Date lll Student: Tom Ma I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this project is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the project. _____, Department Chair EdD Department of Physical Therapy IV /zzbo;c 1 I Date ( Abstract of OUTPATIENT REHABILITATION FOR A PATIENT WITH SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS CONSISTENT WITH ILIOTIBIAL BAND SYNDROME by TomMa A patient with a diagnosis of left lateral thigh pain was seen for physical therapy treatment for a total of7 sessions from 2/24115 to 4/21115 at an outpatient pro-bono physical therapy clinic. Treatment was provided by a student physical therapist under the supervision of a licensed physical therapist. The patient was evaluated at the initial encounter with a subjective and objective examination, and a plan of care was established. Main goal for the patient was to identify the cause of her condition, decrease pain throughout daily activities, and a return to running and playing sports without pain. Main interventions were patient education, therapeutic exercises, motor control training, and manual therapy. At discharge, the patient had a decrease in pain and sleep disturbance, improved strength, motor control , flexibility, posture, gait mechanics, and functional mobility. The patient was discharged to home with a progressive home exercise program and 1-22. -' lb Date v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I acknowledge California State University, Sacramento, Department of Physical Therapy, for allowing me to learn about and treat patients with orthopedic injuries, as well as use a sub-acute rehabilitation. patient for my case study. • Vl TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements ............................................................................................... vi List of Tables ....................................................................................................... viii Chapter 1. GENERAL BACKGROlJND .......................................................................... 1 2. CASE BACKGROlJND DATA ....................................................................... 4 3. EXAMINATION- TESTS AND MEASURES .............................................. 7 4. EVALUATION .............................................................................................. 15 5. PLAN OF CARE- GOALS AND INTERVENTIONS ................................ 18 6. OUTCOMES .................................................................................................. 28 7. DISCUSSION ................................................................................................. 33 References .............................................. .............................................................. 35 Vll LIST OF TABLES Tables Page 1. Medications ................................................................................... 6 2. Examination Data ..................................................................... 13 3. Evaluation and Plan of Care ......................................................... 18 4. Outcomes ............................................................................... 28 Vlll 1 Chapter 1 General Background Iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS) is considered to be one of the most common overuse injuries in the lower extremity, as well as one of the most common causes of lateral knee pain in runners. 14 The overall incidence of ITBS can range from between 1.6% and 52%, dependent on the population examined, 1•2.4 which may include cyclists, soccer players, field hockey players, basketball players, rowers, and military recruits. 1•2•4 While there is a consensus that ITBS is a non-traumatic overuse injury associated with pain and inflammation of structures around the knee, especially the lateral synovial recess, the periosteum of the lateral femoral epicondyle, and the posterior fibers ofthe iliotibial band (ITB), the exact etiology is unclear. 1•2 •4 -8 Potential etiological or risk factors associated with the development of ITBS have been the subject of various studies; however, conflicting evidence limits its applicability. 1•8 Etiological or risk factors have been identified based on the potential those factors have in increasing tension in the ITB. Abnormal kinematics and anatomical variations of the lower extremity such as excessive hip adduction, knee internal rotation, ankle pronation, and leg length discrepancy have been suggested as intrinsic risk factors. 7- 15 Other possible intrinsic risk factors include muscle weakness and decreased flexibility. 7•12•16- 18 Extrinsic risk factors such as rapid increase in mileage, hill training, lower speed or tar and dirt surfaces have also been suggested as contributing factors leading to ITBS. 7•11 •14•15 2 The exact pathogenesis ofiTBS is also controversial. Traditionally, ITBS has been regarded as a frictional syndrome from repetitive movement when the distal portion of the ITB slides anterior to the lateral femoral epicondyle as the knee extends and posterior to the lateral femoral epicondyle as the knee flexes. 11 •12•19-21 Orchard et al. 14 proposed a biomechanical model based on runners, describing an "impingement zone" occurring at, or slightly below, 30° of knee flexion during heel strike and the early stance phase of running. As the ITB travels through this "impingement zone", eccentric contraction of the tensor fascia lata and gluteus maximus muscle decelerates the lower limb at various phases of running, and generates great tension through the ITB. 14 This force in conjunction with repetitive flexion and extension through the "impingement zone" leads to inflammation and pain. 11 •12•14•19-21 However, there are studies that challenge the common belief that ITBS is a frictional syndrome caused by the sliding movement between the ITB and lateral femoral epicondyle. Fairclough et a1. 22 validated that the ITB is not a discrete structure, but simply a thickened part of the fascia lata. The fascia lata is tethered throughout its length to the linea aspera and firmly anchored to the lateral supracondylar region of the femur and to the epicondyle by strong fibrous bands. 22 Thus, the potential for movement of the ITB is limited, and friction is an unlikely cause ofiTBS due to the anatomical relationship ofthe structures. 22 Instead, Fairclough et a1. 22 suggested that the ITB is progressively tensioned from anterior to posterior during knee flexion, and exerts a compressive force into the lateral epicondyle when the fascia tightens, leading to pain and inflammation. 3 The clinical presentation of ITBS varies. Patients will typically complain of a poorly localized pain in the lateral aspect of the knee, commonly at the lateral femoral epicondyle, that may radiate proximally into the outer thigh or distally into the calf. 2•12•20•21 •23 Tenderness, swelling, crepitation or snapping during movement and thickening over the region of the lateral femoral epicondyle of the injured knee may also be present. 2•12•20•21 •23 In mild cases, symptoms are aggravated by running, and the longer the distance or time, the worse the pain becomes until the runner is forced to stop. 3•12 In severe cases, pain can be present even with walking or ascending and descending stairs. 3•12 The prognosis for ITBS varies, but majority of patients will respond well to a multifaceted conservative approach addressing underlying dysfunctions and compensatory patterns involving: control of inflammation, stretching the ITB, strengthening weak musculature, activity modification, soft tissue mobilization, and neuromuscular reeducation. 1-4· 11 •12•16•20•21 •24"27 For patients with chronic ITBS, and who have had persistent symptoms despite conservative treatment, corticosteroid injection or surgical interventions appear beneficial. 28 •29 Unfortunately, to date, the optimal treatment for ITBS remains unclear. 1•4 4 Chapter 2 Case Background Data Examination - History The subject was a 22-year-old female student referred from the Student Health Center at Sacramento State with the diagnosis of "left lateral thigh pain" that started 10 weeks prior to physical therapy evaluation. The patient's chief complaint was constant variable stabbing and aching pain localized at the left lateral femoral epicondyle. The patient also experienced variable pain along her left lateral thigh and variable numbness and pain localized at her lumbar region; however, the patient described the complaint in her lumbar region as more pain than numbness and that it was not her primary complaint. It is important to note that the patient did not complain of problems with her lumbar region until she was further questioned. Initial onset of current condition was described as insidious. The patient recalled walking around downtown the night before she woke up with pain, but denied any event that might have contributed to her current condition and reported that her symptoms have progressively plateaued. The patient denied any lumbar, hip, knee, or ankle problems prior to the current incident, but reported cervical and upper back pain due to a motor vehicle accident two years ago that has since resolved. Lastly, the patient denied fever, malaise, fatigue, weight changes, incontinence, nausea, dizziness or cognitive changes. However, patient admitted to a feeling of numbness that was later described as more painful than numb localized in her lumbar region; otherwise, patient denied any other numbness in the 5 body. Currently, the patient reported that she is of good health and has no other comorbidities. Prior to the current incident, patient lived independently without limitations and was a full time student working two part time jobs that totaled 30-36 hours per week. Patient reported that she has a baseline of constant variable pain of 3/10 throughout all her daily activities but it has not prevented her from participating with school, work, or her social life. Patient stated that she has continued to exercise five to six times per week of at least one hour duration per session as she had before onset of her current complaints, but admitted to significant exacerbation of her baseline symptoms that would last 30-60 minutes post exercise prior to a return to baseline symptoms. Additionally, patient has excluded running and playing sports (soccer, basketball) from her exercise routine because it caused more pain than she could tolerate. Preceding physical therapy intervention, patient did not use or own an assistive device for ambulation. Lastly, patient used ibuprofen one to two times daily, as well as topical medication (icy-hot) and an ice pack as needed to manage her symptoms. The patient's goals were to identify the cause of her current condition, decrease pain throughout all her daily activities, and return to running and playing sports without symptoms. Systems Review The cardiopulmonary and integumentary systems were not affected based on screening questions and integumentary observations. The musculoskeletal and 6 neuromuscular systems were affected based on objective examination, Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS), and patient report. Examination - Medications Table 1 Medications30 Ibuprofen Ingestion, 1-2 times daily Analgesic GI distress, dizziness, nervousness, ringing in the ears, unexplained weight gain, fever, severe skin reaction, difficulty breathing, nausea, flu like symptoms, difficult or painful urination, vision problems, back pain, stiff neck, headache, Icy-Hot (Active ingredients: Menthol, Methyl Salicylate) Topical, as needed Analgesic Allergic reaction such as burning, hypersensitivity, redness, and tingling sensation of skin 7 Chapter 3 Examination- Tests and Measures The patient's deficits were categorized using the International Classifications of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) Model. Body function or structure impairments were identified utilizing the following: the numeric pain rating scale (NPRS), Ober's Test, Noble Compression Test, and palpation were used to assess pain as well as assist with physical therapy diagnosis; manual muscle tests (MMT) were used to assess muscular strength; Ober's Test, Thomas' Test, and hamstring length were used to assess muscle length/flexibility; observation of functional movements inciuding squats, step up/down, and single leg stance were used to assess kinematic abnormalities and motor control. Activity limitations were identified with the Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS), patient report, and observational analysis. Participation restrictions were identified via patient report and Global Rating of Change Scale (GROC). NPRS is a segmented numeric scale in which a respondent selects from 0 to 10 to best reflect the intensity of their pain. The measure has high test retest reliability (r = 0.96), as well as high construct validity when compared to the visual analog scale (correlation ranged from 0.86 to 0.95). 31 An estimate of minimal detectable change (MDC) is approximately 3 NPRS scale points for patients with musculoskeletal problems. 32 The MDC was used to measure improvements in pain for the patient; a change of 3 points indicates that the patient has reached a change that surpassed the threshold of error. 8 MMT evaluates the ability of the muscle tested to meet or adapt to the resistance provided by the examiner or the force of gravity. The examiner evaluates the muscle(s) tested on numerical scores ranging from 0, which represents "no activity," to 5, which represents "normal" or best possible response. 33 Based on a systematic review conducted by Cuthbert et al. in 2007, test-retest reliability was found to be moderate to excellent (ranging from 0.63 to 0.98). Validity requires further testing, but several authors argue that MMT has content validity because the test construction is based on known physiological, anatomic and kinesiologic principles. 34 Although MCD or MCID has not been established for MMT, the authors suggested that scores must change more than one full grade in order to be confident that a true change in strength has occurred. 34 The MMT was used to measure improvements in strength for the patient; a change in one full grade would indicate that a true change had occurred. Currently, there are no specific prognostic factors or clinical prediction rule for ITBS predictive ofpatient condition or outcome. 1.4 As stated in Chapter 1, the evidence for potential risk factors associated with ITBS are conflicting, therefore, this limits its applicability towards prognosis or development of a clinical prediction rule. There are also no single diagnostic protocol for ITBS, and ITBS tend to be diagnosed on the basis of patient history and presentation, complemented by clinical findings and absence of other pathologies. 1•3•7•10•12•16•17•21 •22•25 •28 •29 Positive Noble compression test is often used to confirm the diagnosis ofiTBS 1•7•10•12•17•18•28 •29 and positive supplementary tests such as the Ober's test are associated with ITBS. 1•10•18•26 However, the two tests have not 9 been validated for patients with ITBS, but seem to have good face validity. 1 MRI may be used if there is doubt about the diagnosis and to exclude other pathologies. 1•5 The Noble compression test may be used to provoke symptoms to confirm the diagnosis of ITBS and has been reported to have moderate inter-rater reliability. 18•35 Otherwise, no other psychometric properties have been reported for the Noble Compression test. 1 The Noble compression test is performed by positioning the patient in supine or sidelying with the affected knee up and flexed to 90°; the clinician then applies pressure to the iliotibial band over the lateral femoral epicondyle and gradually extends the knee. A positive test will be indicated by complaint of pain over the lateral femoral epicondyle or the patient's comparable sign as the knee approaches 30° of flexion. 12 The Ober test measures the flexibility or the length of the iliotibial band and has been reported to have good inter-rater as well as intra-rater reliability (ICC= 0.90). 35 •36 The patient is positioned lying on their side with the tested extremity up. The clinician flexes the knee to be tested to 90°, the thigh is then passively abducted and extended to catch the iliotibial band over the greater trochanter. Next the limb is passively allowed to adduct via gravity as far as possible. If the leg can be passively adducted to horizontal at best, this constitutes moderate tightness, and if it cannot be passively adducted to horizontal, this is maximal tightness. The degree of adduction of the hip reflects the flexibility of the iliotibial band. 37 Noehren et al. performed a cross sectional study between 17 patients with ITBS and 17 healthy patients, and determined the MDC 10 for the Ober test in that specific study to be 3.8°. 18 No other psychometric properties for the Ober test have been reported. 1 Observation of functional movements (squats, single leg stance, step ups/downs), posture, and gait was used to clinically assess impairments found in alignment and kinematics, as well as motor control of the patient. Whatman et al. 38 compared the quality of movement patterns of a range of lower extremity movements from visual rating by physical therapists against camera motion analysis systems. They found that mean intra-rater agreement was substantial (percent agreement [PA] 88%; agreement coefficient 1 [ACl] = 79- = 0.60-0.78), inter-rater agreement ranged from fair to substantial (PA = 67-80%; ACl = 0.37-0.61), sensitivity (0.80) and specificity (0.50) were all acceptable for all tests except for the drop jump. High sensitivity ensures those who actually have poor alignment will be detected by the physical therapists. Using experienced clinicians (diagnostic odds ratio [DOR] = 1.6-2.8) and observation of slower movements (DOR = 4.9) improved rating accuracy. 38 In agreement with the study conducted by Whatman et al. 38 , a systematic review conducted by Maclachlan et al. 39 found clinically acceptable results, in terms of the accuracy of observer ratings. These findings were achieved when slow, speedcontrolled movements such as single leg or two legged squats were rated. Conversely, lower levels of agreement were evident when faster, more explosive movements such as drop jump and cutting maneuvers were assessed. While multi-camera, three dimensional motion analysis are recognized as the gold standard in kinematic and movement assessment, the above evidence conveys that visual rating by physical 11 therapists can be a valid tool for identification of impairments. 38·39 The information gained from visual observation of the current patient aided in the clinical decision making process and determination of appropriate interventions. The LEFS is an ICF activity level outcome measure that evaluates the functional level of a wide range of patients with lower-extremity orthopedic conditions who have various disability levels, comorbidities, treatments, and age. 40 The LEFS has 20 questions with a total possible score of 80; a lower score will indicate a higher level of disability to complete everyday tasks. For patients with various lower extremity injuries, the standard error of measurement (SEM9s) is 3.9 points, the minimal detectable change (MDC9s) is 9 points, and the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) is also 9 points. 40 The LEFS can be used to assess initial activity and/or functional level, set functional goals, measure ongoing progress, as well as measure outcome of an intervention(s) for patients with ITBS. The MDC and MCID was used to measure improvements in the patient. Improvement of 9 points for the MDC and MCID will indicate that the patient has reached a change that has surpassed the threshold for error inherent in the measure and considered to be clinically important, respectively. The Global Rating of Change Scale (GROC) is an ICF participation level outcome measure to determine if the patient's health condition has improved or deteriorated through a course of care to determine the efficacy of the care. GROC asks the patient to assess his or her current health status, and compare it from the time that they began treatment on an 11 or 15 point numerical or visual analog scale, dependent 12 on which GROC version was given. The "global" aspect of the GROC distinguishes it from other outcome measures that are typically directed towards one specific dimension of the patient's health status; instead, the GROC allows a patient to decide what they consider as important in their health status. 41 The MDC calculated from the SEM from a single study was 0.45 points on an 11 point scale; the MCID calculated from five studies was 2 points on an 11 point scale; and a cut of score of ±5 on a 15 point scale was described in a single study as clinical important. 41 Since the patient in this case report utilized the 15-point version of the GROC, an improvement of 5 points would indicate that a change in the patient status was due to the course of care. 13 Table 2 Examination Data 1. pain B)NPRS reported by patient during Ober's Test 2. Flexibility 2. C)NPRS reported by patient during Noble Compression Test Muscle Length Tests 3. Strength 3. MMT 4. Motor Control 4. Observation of Functional Movements A) Left lateral thigh (femoral epicondyle, region along ITB) of constant variable nature: overall (3-9/1 0), at rest (3/1 0), aggravation with activity (9/10) Lumbar region: intermittent variable (01/10) B) 7/10, comparable pain C) 7/10, comparable pain 2. 3. 4. Hamstring length (popliteal angle test): R = 142°, L = 132°; no provocation of symptoms Hip flexors via Thomas' Test: R knee flexed = 10° from table, L knee flexed = 27° from table; R knee straight= parallel with table, L knee straight= 10° from table; no provocation of symptom/chief complaint ITB via Ober's Test: R = -3° past horizontal plane of table; L = 7° away from horizontal plane of table; provocation of symptoms/chief complaint Hip abductors: L = 4/5, R = 5/5 External rotators: L = 4/5, R = 515 Squat: body (center of mass) deviates over L LE > R LE during descend associated with L hip adduction; no provocation of symptoms Step up: no abnormalities observed with R LE; (+)Trendelenburg observed with L LE with provocation of symptoms/chief complaint Step down: (+)Trendelenburg observed bilaterally; no provocation of symptom/chief 14 2. Posture 2. Observational analysis 2. 3. Gait Kinematics 3. Observational analysis 3. 4. Sleeping Pattern 4. Patient report 4. - Decreased weight bearing on L side during standing and sitting as observed with lateral lean and weight shift to R (+)Trendelenburg observed with L LE, decreased stance time with L LE leading to decreased step length with R LE; increasing step length with L LE provoked symptoms/chief complaint Unable to sleep through the night secondary to pain; difficulty finding a comfortable position during initiation of sleep; waking at least twice a night during positional changes such as rolling towards R or laying on L LE with knee flexed Unable to maintain workout routine secondary to pain; unable to run or play soccer; only able to tolerate elliptical for <30 minutes; symptoms will be aggravated to 9110 post exercise that lasts approximately 30-60 minutes NPRS = Numeric Pain Rating Scale; R = Right; L = Left; MMT = Manual Muscle Test;(+)= Positive; LE =Lower Extremity; LEFS =Lower Extremity Functional Scale 15 Chapter4 Evaluation Evaluation Summary Patient was a 22-year-old female who was a full time student and part time employee at two different jobs that totaled 30-36 hours per week. The patient was referred from the Student Health Center at Sacramento State to Pro-Bono Clinic with a 10-week history of constant and variable pain in her left lateral thigh. This was the patient's first attempt at treatment since initial onset of symptoms. The impairment to body structure and function included: pain, range of motion deficits, decreased strength, and poor motor control. The patient's activity limitations included: impaired functional mobility (work or school activities, sporting activities, squatting, performing heavy activities around home, walking a mile, going up or down a flight of stairs, standing or sitting for 1 hour, running on even or uneven ground, making sharp turns while running fast, hopping, and rolling over in bed), impaired posture, impaired gait kinematics, and sleep disturbance. The patient's participation limitations included alteration in hobbies such as the inability to maintain her workout routine or play sports. Diagnostic Impression The patient had signs and symptoms consistent with ITBS, this was classified on the basis of the patient's history and presentation, complemented by clinical findings and absence of other pathologies. The patient's chief complaint stemmed from a nontraumatic injury, and it was inferred from the subjective examination that she was very physically active, which indicated pathologies associated with overuse. Other overuse 16 pathology such as osteoarthritis was ruled out because of the patient's age, no complaints of morning stiffness, and hip flexion and internal rotation was not limited by pain. The patient had constant variable pain at the lateral femoral epicondyle and along her lateral thigh, which was provoked with activities such as running and climbing stairs, as well as with palpation. The patient did not have signs of swelling or inflammation. Upon objective examination, the patient was found to have hip abductor weakness, abnormal kinematics of the lower extremity ~n standing and during movement, as well as decreased muscle length of the ITB, hip flexors, and hamstrings. Additionally, the patient tested positive for Noble Compression Test and Ober's test, both of which replicated the patient's symptoms as a comparable pain. Based upon the above examination, it was concluded that the patient had signs and symptoms consistent with ITBS. G-Codes Current with modifier: 08978 CJ Goal with modifier: 08979 CI Prognostic Considerations While there are currently no prognostic factors or clinical prediction rules associated with ITBS, the current evidence, albeit coming from studies with small and heterogeneous samples, suggests that conservative treatment and activity modifications appear beneficial in the management ofiTBS. 1•4 Additionally, it has been suggested that an implementation of care involving staged application of various types of rehabilitation services for musculoskeletal injuries appears to result in more rapid and 17 sustained recovery. 42 Thus, the patient has good rehabilitation potential if she adheres to a conservative treatment plan that addresses her underlying dysfunction and compensatory patterns. Expected Discharge Destination/Status The patient was discharged after 7 sessions with an independent and progressive home exercise program. 18 Chapter 5 Plan of Care-Goals and Interventions Table 3 Evaluation and Plan of Care PROBLEM Short Term Goals (4 weeks) • • Pain at baseline as measured by the NPRS • L lateral thigh (3-9/1 0) • Lumbar region (0-1/10) • Ober's Test (7/10) Noble • Compression Test (7/10) Reduce pain as measured by the NPRS L lateral thigh (1-6/10) • Lumbar region (0/10) • Ober's Test (4/10) Noble • Compression Test (4110) • Reduce pain as measured by the NPRS • L lateral thigh (0-3/10) • Lumbar region (0/10) • Ober's Test (1/1 0) Noble • Compression Test (1110) • • Interventions are Direct or Procedural unless they are marked: (E) = Educational intervention Interventions were performed once a week for seven sessions over of weeks the (E) Monitor use of medication for pain reduction during each patient visit; provide education and references about the difference between NSAID (antiinflammatory and analgesic) and acetaminophen (analgesic only) (E) Educate patient of the proposed etiology and pathology ofiTBS and why activity modifications and rest are important for recovery. Activity modifications included: sleeping with a pillow to prevent adduction ofLEs or rolling during sleep, avoidance of activities that exacerbate her symptoms (eg. running, soccer) or stopping prior to threshold of 19 • • • Decreased flexibility at baseline as measured by muscle length tests • Hamstring: R= 142°, L= 132° Hip flexors: • R = parallel with table, L = 10° from table • ITB: R= -3° past horizontal plane of table, L = 7° from horizontal plane of table Improve flexibility as measured by muscle length tests • Hamstring: R=152°,L= 142° • Hip flexors: R =past parallel with table, L =5° from table • ITB: R= remains past horizontal plane of table, L= 3° from horizontal plane of table Improve flexibility as measured by muscle length tests • Hamstring: R=152°,L= 152° • Hip flexors: R=remains past parallel with table, L = parallel with table • ITB: R= remains past horizontal plane oftable, L =past horizontal plane oftable • • • (eg. elliptical), and choosing alternative activities that does not exacerbate her symptoms (eg. weight lifting, arm bike, swimming with UEs only) Lumbar traction in supine, Grade II, 2x30seconds; discontinued after cessation pain in lumbar region Soft tissue massage and myofascial release along symptomatic area, 25minutes per session Ice massage over symptomatic area, 25minutes, but did not perform every session Hip mobilization: ~ Lateral glide, Grade III, 2x30sec ~ Caudal glide, Grade III, 2x30sec ~ PA glide, Grade III, 2x30sec PA glide in ~ FABER, Grade III, 2x30sec Manual stretching of surrounding musculature ofthe hip (hamstring, hip flexors, tensor fascia lata) ~ Static stretching to be part of home exercise program (see below) ~ Tack and pull forTFL, 23sets, 30-60 seconds per set (E) Home exercise program with stretching 20 Decreased strength at baseline as measured by MMT • Hip abductors: L = 4/5, R = 515 External • rotators: L = 4/5, R = 515 Improve strength as measured by MMT • Hip abductors: L= 5/5, R= Improve strength as measured by MMT • Hip abductors: L=5/5, R= 515 • External rotators: L= 5/5, R= 515 • 515 • External rotators: L= 5/5, R= 515 • • • • exercises for LE (hamstring, hip flexors, tensor fascia lata, piriformis, gluteus medius, rectus femoris) );> 3 sets x 30-60 seconds Several of the exercises below was part of the patient's (E) home exercise program; "7" indicates progression; exercises was progressed once patient was able to perform 3xl2-15 or 3x30sec and subjectively reported that the exercise was no longer a challenge; exercises can be progressed with increasing the number of repetitions, adding elastic bands, or increasing isometric durations; patient encouraged to complete each exercises for 3xl2-15, 3x30sec, or to fatigue, whichever one comes first Side lying hip abduction 7 sidelying hip abduction with elastic band Single leg stance 7 single leg stance with toe tab in lateral/oblique/anterior direction 7 single leg RDL with contralateral reach Tri-planar lunges 7 plyometric tri-planar lunges Squats 7 squats with elastic band around thigh 7 squats with elastic band around thigh with slow eccentric descend 21 • • • Impaired motor control at baseline as measured by observation of functional movements • Squat: uneven distribution of weight during movement with deviation towards L LE during descend • Step up: (+)Trendelenbur g with L LE only, provocation of symptoms • Step down: (+)Trendelenbur g observed bilaterally, L > R Improve motor Improve motor control as ·control as measured by measured by observation of observation of functional functional movements movements Squat: even • Squat: even distribution of distribution of weight during weight during movement movement Step up: • • Step up: (()Trendelenbur )Trendelenbur g withL LE, g withL LE, minimal no provocation of provocation of symptoms symptoms • Step down: • Step down: (()Trendelenbur )Trendelenbur g observed g observed bilaterally bilaterally • • • • • with pause "in the hole" prior to explosive concentric phase Monster walks 7 monster walks with elastic band 7 monster walks with elastic band and catching/throwing ball in sagittal and transverse plane Double leg bridging 7 double leg bridging with elastic band and/or single leg bridging Trunk strength: quadruped, static plank, dynamic plank Main focus was neuromuscular reeducation to improve abductors activation and control to decreased Trendelenburg sign; time performed ranged from 5 to 15 minutes; sets and reps varied, but attempted to have patient reach fatigue before stopping Squatting with visual (mirror), verbal, and tactile (PNF provided by SPT) cues 7 squatting without cues Step up with visual (mirror), verbal, and tactile (elastic band around thigh pulling in opposing direction to prevent hip adduction) cues 7 progressed with height of steps and removal of cues Step down with visual (mirror), verbal, and tactile (elastic band around thigh pulling in opposing direction to 22 prevent hip adduction) cues ~ progressed with height of steps, removal of cues, and eccentric control Impaired functional mobility at baseline as measured by LEFS • LEFS = 53/80 Improve functional mobility as measured by LEFS • LEFS = 62/80 Improve functional mobility as measured by LEFS • LEFS = 71/80 • The aforementioned treatment above that addresses pain, flexibility, strength and motor control will indirectly improve ability to perform activities Impaired posture at baseline as measured by observational analysis • Decreased weight bearing on L side during standing and sitting Improve posture as measured by observational analysis • Equalize weight towards midline during standing and sitting Improve posture as measured by observational analysis • Maintain weight at midline during standing and sitting • (E) Postural reeducation with visual, verbal, and tactile cues; explain the proposed model on how poor posture in standing (eg. hip adduction) can increase strain on ITB and provocation of symptoms The treatment of decreasing pain, improving flexibility, strength and motor control will indirectly improve posture Improve gait mechanics as measured by observational analysis • ()Trendelenbur gLLE, increase stance time with L LEas tolerated to achieve stride length symmetry between L and RLE, able to take Improve gait mechanics as measured by observational analysis • ()Trendelenbur g L LE, stride length symmetry between L and RLE, able to take large strides with no provocation of symptoms Impaired gait mechanics at baseline as measured by observational analysis • (+)Trendelenbur gLLE, decreased stance time with L LE leading to decreased stride length with R LE, increased stride length provoked symptoms • • • Gait training exercises: correct deviations and asymmetry as tolerated with visual, verbal, and tactile cues; time varied per session };;> Increase weight bearing on L LE to achieve a larger stride with L LE, timing of gait mechanics, hip abductors activation/contr ol The aforementioned treatment above that 23 strides with minimal provocation of symptoms Sleep disturbance at baseline as measured by patient report • Difficulty finding a comfortable position during initiation of sleep, waking up throughout the night (>2) during position changes Decrease sleep disturbance as measured by patient report • Able to find a comfortable position during initiation of sleep and be able to sleep through the night with minimal (<2) disturbances Decrease sleep disturbance as measured by patient report • Able to sleep through the night with no disturbance Decreased/altered participation with hobbies at baseline as measured by patient report • Unable to maintain gym routine (eg. elliptical for <30 minutes), run or play sports (soccer, basketball) Improve participation with hobbies as measured by patient report • Able to perform elliptical for 30 minutes with minimal irritability and no increase of symptoms afterwards • Able to jog without aggravation of pain as tolerated (time is arbitrary) Able to • perform athletic movements at 50% of Improve participation with hobbies as measured by patient report • Able to perform elliptical for 30 minutes with no irritability and no aggravation of symptoms afterwards • Able to run without aggravation of pain as tolerated (time is arbitrary) • Able to perform athletic movements at maximal • • • • addresses pain, flexibility, strength and motor control will indirectly improve gait mechanics (E) Activity modification: sleeping with pillow in between legs to prevent adduction of L LE during rolling towards R, taking note of specific position that causes minimal pain during initiation of sleep and utilize that position every night The aforementioned treatment above that addresses pain and flexibility might indirectly decrease sleep disturbance (E) Patient education about importance of pain management and not exercising past the threshold that increases her symptoms The aforementioned treatment above that addresses pain, improving flexibility, strength and motor control will indirectly improve ability to perform activities 24 maximal intensity as intensity as perceived by perceived by the patient (eg. the patient (eg. cuts, change cuts, change of speed) of speed) L = Left; R = Right; NPRS = Numenc Pam Ratmg Scale; (E) = Educational Intervention; NSAID = Non Steroid Anti-Inflammatory Drug; ITB = Iliotibial Band; ITBS = Iliotibial Band Syndrome; LEs = Lower Extremities; UEs =Upper Extremities; eg. =Example Given; PA =Posterior Anterior; FABER = Flexion Abduction External Rotation; TFL =Tensor Fascia Lata; MMT =Manual Muscle Test; RDL = Romanian Deadlift; (+) =Positive; (-) =Negative; SPT = Student Physical Therapist; PNF = Proprioceptive Neuromusuclar Facilitation; LEFS = Lower Extremity Functional Scale 25 Overall Approach During this episode of care, the patient was seen once a week for seven sessions over the span of eight weeks. The overall treatment strategy utilized was a multifaceted approach with an emphasis on therapeutic exercises and neuromuscular control to address all deficits. The plan of care was constructed to address the body structure and function impairments and activity limitations identified from the subjective and objective examinations. By addressing the impairments found in the body structure and function and activity categories, the multifaceted approach indirectly improved the participation restrictions caused by ITBS. PICO question: For a 22 year oldfemale with sub-acute ITBS, what is the best combination of conservative treatment (i.e. not surgical) for the management of ITBS? Vander Wrop et al. 1 conducted an extensive, quality-controlled, systematic review; one of their conclusions was that there is limited evidence to support a specific treatment ofiTBS. Five studies on the conservative treatment ofiTBS met the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review, with evidence level between 1b to 2b according to the Centre of Evidence Based Medicine. Overall, the results on the conservative treatment of ITBS provided some evidence of the effectiveness and benefits of pain medication or injection, stretching of the ITB, hip abduction exercises, and advice about training. 1 Unfortunately, no randomized clinical trials have investigated the benefit ofthese different treatments in isolation. 1 26 While there is no consensus for which conservative treatment is superior, numerous studies, clinical reviews and systematic reviews have suggested that conservative treatment plans with a multifaceted approach appears to be effective in the management of ITBS. 1-4· 11 •12•16•17•20 •24"27 Several clinical reviews, cohort studies, and case reports have outlined conservative treatment progressions, beginning with treatment of the acute inflammatory response, progressing through a corrective treatment phase, and an eventual return to regular activities. A summary of the treatment progression is outlined in the next paragraph. 3•12•16•17.24 -27 Care in the acute phase focuses on measures to relieve pain and inflammation such as ice, oral NSAIDs, corticosteroids, and soft tissue massage have been suggested. Patient education is critical to a successful outcome, as activity limitation or modifications are needed to reduce the repetitive stress at the lateral femoral epicondyle. Once acute inflammation subsides, stretching exercises addressing all flexibility deficits can begin, with particular attention given to increasing the length of the TFL and ITB complex. Strengthening approaches for ITBS have supported strengthening of the hip abductors, some have recommended multidimensional movement patterns involving weight shift, and other aspects of hip abductor function as treatment strategies. Improvement with neuromuscular control during gait has also been suggested as a useful approach for ITBS. Gradual return to activity is dependent upon being able to perform exercises or movements with proper form and no pain. 27 Since there is no evidence that suggests a specific combination of treatment that is superior to another, I decided to utilize a multifaceted treatment progression outlined by clinical reviews, cohort studies, and case reports that had successful outcomes. 28 Chapter 6 Outcomes Table 4 Outcomes OUTCOMES :?; :~~~¥.: ' ;"Rf'lnV,J!'ISJ~' f_,,' ,_,_,. ~:"''.!'' "" Outcome Initial Follow-up NPRS via patient report, Ober's Test, Noble Compression Test 1. l. Change Goal Met (YIN) 2. 3. 4. Muscle length tests 1. 2. 3. Left lateral thigh of constant variable nature: overall (3-9/10), at rest (3/10), aggravation with activity (9/10) Lumbar region: intermittent variable (0-1110) Ober's Test: (7/10) Noble Compression Test: (7/10) Hamstring length (popliteal angle test): R = 142°, L = 132° Hip flexors via Thomas' Test: R knee flexed = 1oo from table, L knee flexed= 27° from table; R knee straight = parallel with table, L knee straight = 10° from table ITB via Ober's Test: R = -3° past 2. 3. 4. Left lateral thigh of intermittent variable nature: overall (0-4/10), at rest (0-111 0), aggravation with activity (3-411 0) Lumbar region: (0/10) Ober's Test: (1/10) Noble Compression Test: (1110) • 1. 2. 3. 4. NPRSMDC=3 points Left lateral thigh pain decreased by 3-5 points Lumbar pain decreased by 1 point Ober's Test pain decreased by 6 points Noble Compression Test pain decreased by l.Y 2. y 3. y 4. y 6po~ 1. 2. 3. Hamstring length (popliteal angle test): R = 147°, L = 145° Hip flexors via Thomas' Test: L/R knee flexed = parallel with table, L/R knee straight = parallel with table ITB via Ober' s Test: R = -5° past horizontal plane of table; L = 0° from horizontal plane oftable • I. 2. 3. Mean value of popliteal angle for women43 = 152° (SD = 10.6°) Hamstring length: R=+5°,L= +12° Thomas' Test improved to negative Ober's Test improved to negative l.N 2. y 3. y 29 MMT 1. 2. Observation of functional movements 1. 2. 3. ; ;"~:?:!,;""''I" "~ horizontal plane of table; L = 7° away from horizontal plane of table Hip abductors: L = 4/5, R = 515 External rotators: L = 4/5, R = 515 Squat: center of mass deviates over L LE > R LE during descend, no provocation of symptoms Step up: no abnormalities observed with R LE; (+)Trendelenburg observed with L LE with provocation of symptoms/chief complaint Step down: (+)Trendelenburg observed bilaterally with no provocation of symptoms/chief complaint Outcome "-"' -~ ::', Initial LEFS l. ~!"J~- 1. Hip abductors: L l. = 5/5, R = 5/5 2. 1. 2. 3. External rotators: L = 5/5, R = 515 Squat: no deviations observed Step up: no abnormalities observed with R LE; (+)Trendelenburg observed with L LE, but noted improvements in consecutive weeks, no provocation of symptoms/chief complaint Step down: no abnormalities observed with R LE (+)Trendelenburg observed with L LE, but noted improvements in consecutive weeks\ 2. l. 2. 3. L hip abductors improved by 1 point L external rotators improved jlyl_p()int Squats: improved to even distribution of weight during movement Step ups: improvements made with L LE, but continues to have (+)Trendelenburg sign; improved to no provocation of symptoms/chief complaint Step downs: improvements made with L LE, but continues to have (+)Trendelenburg sign; Jln"·T Follow-up Change l.Y 2. y l.Y 2.N 3.N ~ Goal Met (YIN) LEFS 57/80 1. LEFS 75/80 • l. MCDandMCID = 9 points Increased by 18 points, or 2 MCD andMCID l.Y 30 Observational analysis of posture 1. Observational analysis of gait 1. Patient report of sleep disturbance 1. Decreased weight bearing on L side during standing and sftting (+)Trendelenburg observed with L LE; decreased stance time with L LE leading to decreased stride length with R LE; increasing stride length with L LE provokes patient's symptoms/chief complaint Unable to sleep through the night secondary to pain; difficulty finding a comfortable position during initiation of sleep; waking through night during position changes, especially with rolling towards R 'i:~"t:<.~~ t~;;,:::~o11:r ,,,.c,:, 1. 1. 1. No deviations in weight bearing in standing and sitting (-)Trendelenburg observed with L LE; normalized gait symmetry in stance time and stride; increasing stride length with L LE still provokes symptoms/chief complaint 1. Improved postural deviations l.Y 1. Improved to (-) Trendelenburg sign and normalized gait symmetry; but continues to be provoked by longer strides with L LE l.N Able to sleep through the night with pillow in between legs; no difficulty finding a comfortable position during initiation of sleep 1. Improved to be able to sleep through the night and no longer have difficulty finding a comfortable position during initiation of sleep l.Y - Outcome Initial Follow-up Change Patient report of participation in hobbies 1. 1. 1. Unable to maintain workout routine secondary to pain- unable to run or play soccer, only able to tolerate elliptical for <30 minutes; symptoms will be aggravated to 9/10 post exercise that lasts -30 minutes after cessation Able to perform ·elliptical for 30 minutes prior to ons"et/aggravation of symptoms to 34/1 0 that lasts for -1 0 minutes after cessation; able to play soccer and run, but experiences aggravation of symptoms to 34/10 that lasts -10 minutes after but Goal Met (YIN) Improvements made, but symptoms continues to be aggravated by hobbies l.N 31 GROC 1. Not applicable (n/a) stated that it did not hinder her performance as much as before 1. +7 1. +5 indicates a clinically important change; patient reported a + 7 1. n/a L = Left; R = Right; ITB = Iliotibial band; NPRS = Numeric Pain Rating Scale; MDC = Minimal detectable change; SD =Standard deviation; Y =yes; N =No; LEs =Lower Extremities;(+)= Positive;(-)= Negative; LEFS =Lower Extremity Functional Scale; MCID =Minimal clinical important difference; GROC = Global Rating of Change Scale 32 Discharge Statement The patient attended Pro Bono Clinic for treatment with the diagnosis of "lateral thigh pain" for seven visits over a span of eight weeks. The patient received manual therapy, soft tissue massage, manual stretching, therapeutic exercises, and patient education to address signs and symptoms consistent with ITBS. Not all of the patient's goals were met during this episode of care; however, significant progress was achieved. Objectively, the patient achieved improvements associated with decrease in pain, increase in strength and flexibility, as well as improvement with motor control and gait kinematics. While the patient continued to be limited with participation of her hobbies, she reported that she felt a significant improvement in her condition due to this episode of care. Additionally, the GROC of+7 indicated that this episode of care made a significant improvement in her health status. Upon discharge, the patient was independent with a home exercise program, and was provided instructions on how to progress the home exercise program. No follow up visits were made. DC G-Code with modifier: G8979 CI 33 Chapter 7 Discussion Overall, the plan of care provided for the patient was successful. While the patient did not meet all of the proposed long-term goals, significant progress and meaningful changes were made during this episode of care. The patient objectively met more than half the proposed goals, and subjectively reported an overall improvement with her condition, as well as her ability to perform activities and participate with hobbies. Improvements can be attributed to the patient's participation with Pro-Bono Clinic, as shown by the GROC score and patient report, and interventions that improved her underlying dysfunctions and compensatory patterns. Several factors might have contributed to the patient not reaching all proposed long term goals, such as: limited number of visits allotted per week, inability of the student physical therapist to immediately diagnose ITBS during initial evaluation, inadequate adherence to the home exercise program and recommendation to limit aggravating activities as reported by the patient. The patient responded to the treatment provided as expected. This expectation came from utilizing a multifaceted conservative treatment approach outlined by previous studies and cases that had successful outcomes. The multifaceted conservative treatment approach that was utilized for this patient was a strength of this episode of care, as a variety of progressive interventions were provided to address the patient's underlying dysfunction and compensatory patterns. There were several limitations throughout this episode of care. Limited amount of visits hindered the 34 evaluation process as well as decreased the treatment frequency allotted to the patient; this might have affected the patient's outcome. Another limitation was the poor objective data obtained for motor control of squats, step up, and step down, as well as for impaired posture and gait mechanics. While observational analysis can provide information on gross impairments or dysfunction, it is difficult to objectively measure visual observation; this becomes problematic to objectively assess whether a patient has regressed or made improvements. Future studies should obtain measurable and objective data for the aforementioned movements via force plates to assess weight distribution, plumb line hanging from a ceiling to assess posture, and motion cameras to assess abnormal kinematics. Lastly, ankle kinematics was not assessed during this episode of care, and there is evidence suggesting that the ankle has a role in the development ofiTBs.?- 10•13 •14 Although conservative treatment appears to be beneficial in the management of ITBS, the evidence in support of such management appears to be limited and of insufficient quality at this time. Further research of the clinical effect of conservative therapies, or of a specific conservative therapy in the treatment of ITBS, will be of great benefit to the evidence based management of this condition. Until then, the evidence utilized to assist with management of patients with ITBS is based on anecdotal evidence from studies and case reports with small and heterogeneous samples. 35 References 1. van der Worp MP, van der Horst N, de Wijer A, Backx FJ, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW. Iliotibial band syndrome in runners: a systematic review. Sports medicine. Nov 1 2012;42(11):969-992. 2. Kirk KL, Kuklo T, Klemme W. Iliotibial band friction syndrome. Orthopedics. Nov 2000;23(11):1209-1214; discussion 1214-1205; quiz 1216-1207. 3. Fredericson M, Wolf C. Iliotibial band syndrome in runners: innovations in treatment. Sports medicine. 2005;35(5):451-459. 4. Ellis R, Hing W, Reid D. Iliotibial band friction syndrome--a systematic review. Manual therapy. Aug 2007;12(3):200-208. 5. Nishimura G, Yamato M, Tarnai K, Takahashi J, Uetani M. MR findings in iliotibial band syndrome. Skeletal radiology. Sep 1997;26(9):533-537. 6. Nemeth WC, Sanders BL. The lateral synovial recess of the knee: anatomy and role in chronic Iliotibial band friction syndrome. Arthroscopy : the journal of arthroscopic & related surgery : official publication of the Arthroscopy Association ofNorth America and the International Arthroscopy Association. Oct 1996;12(5):574-580. 7. Messier SP, Edwards DG, Martin DF, et al. Etiology of iliotibial band friction syndrome in distance runners. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. Jul 1995;27(7):951-960. 36 8. Louw M, Deary C. The biomechanical variables involved in the aetiology of iliotibial band syndrome in distance runners - A systematic review of the literature. Physical therapy in sport: official journal of the Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Sports Medicine. Feb 2014;15(1):64-75. 9. Ferber R, Noehren B, Hamill J, Davis IS. Competitive female runners with a history of iliotibial band syndrome demonstrate atypical hip and knee kinematics. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. Feb 201 0;40(2):52-58. 10. Grau S, Krauss I, Maiwald C, Axmann D, Horstmann T, Best R. Kinematic classification of iliotibial band syndrome in runners. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. Apr 2011;21(2):184-189. 11. McNicol K, Taunton JE, Clement DB. Iliotibial tract friction syndrome in athletes. Canadian journal ofapplied sport sciences. Journal canadien des sciences appliquees au sport. Jun 1981 ;6(2):76-80. 12. Noble CA. Iliotibial band friction syndrome in runners. The American journal ofsports medicine. Jul-Aug 1980;8(4):232-234. 13. Noehren B, Davis I, Hamill J. ASB clinical biomechanics award winner 2006 prospective study ofthe biomechanical factors associated with iliotibial band syndrome. Clinical biomechanics. Nov 2007;22(9):951-956. 14. Orchard JW, Fricker PA, Abud AT, Mason BR. Biomechanics of iliotibial band friction syndrome in runners. The American journal ofsports medicine. May-Jun 1996;24(3):375-379. 37 15. Taunton JE, Ryan MB, Clement DB, McKenzie DC, Lloyd-Smith DR, Zumbo BD. A retrospective case-control analysis of2002 running injuries. British journal ofsports medicine. Apr 2002;36(2):95-1 01. 16. Beers A, Ryan M, Kasubuchi Z, Fraser S, Taunton JE. Effects of Multi-modal Physiotherapy, Including Hip Abductor Strengthening, in Patients with Iliotibial Band Friction Syndrome. Physiotherapy Canada. Physiotherapie Canada. Spring 2008;60(2):180-188. 17. Fredericson M, Cookingham CL, Chaudhari AM, Dowdell BC, Oestreicher N, Sahrmann SA. Hip abductor weakness in distance runners with iliotibial band syndrome. Clinical journal ofsport medicine : official journal of the Canadian Academy ofSport Medicine. Jul2000;10(3):169-175. 18. Noehren B, Schmitz A, Hempel R, Westlake C, Black W. Assessment of strength, flexibility, and running mechanics in men with iliotibial band syndrome. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. Mar 2014;44(3):217-222. 19. Evans P. The postural function of the iliotibial tract. Annals of the Royal College ofSurgeons ofEngland. Jul1979;61(4):271-280. 20. Orava S. Iliotibial tract friction syndrome in athletes--an uncommon exertion syndrome on the lateral side ofthe knee. Britishjournal ofsports medicine. Jun 1978;12(2):69-73. 38 21. Renne JW. The iliotibial band friction syndrome. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. Dec 1975;57(8):1110-1111. 22. Fairclough J, Hayashi K, Toumi H, et al. The functional anatomy of the iliotibial band during flexion and extension of the knee: implications for understanding iliotibial band syndrome. Journal ofanatomy. Mar 2006;208(3):309-316. 23. Ekman EF, Pope T, Martin DF, Curl WW. Magnetic resonance imaging of iliotibial band syndrome. The American journal ofsports medicine. Nov-Dec 1994;22(6):851-854. 24. Baker RL, Souza RB, Fredericson M. Iliotibial band syndrome: soft tissue and biomechanical factors in evaluation and treatment. PM & R : the journal of injury, function, and rehabilitation. Jun 2011 ;3(6):550-561. 25. Lavine R. Iliotibial band friction syndrome. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine. 201 0;3(1-4): 18-22. 26. Pettitt R, Dolski A. Corrective neuromuscular approach to the treatment of iliotibial band friction syndrome: a case report. Journal ofathletic training. Jan 2000;35(1 ):96-99. 27. Shamus J, Shamus E. The Management of Iliotibial Band Syndrome with a Multifaceted Approach: A Double Case Report. International journal ofsports physical therapy. Jun 2015;10(3):378-390. 39 28. Gunter P, Schwellnus MP. Local corticosteroid injection in iliotibial band friction syndrome in runners: a randomised controlled trial. British journal of sports medicine. Jun 2004;38(3):269-272; discussion 272. 29. Hariri S, Savidge ET, Reinold MM, Zachazewski J, Gill TJ. Treatment of recalcitrant iliotibial band friction syndrome with open iliotibial band bursectomy: indications, technique, and clinical outcomes. The American journal ofsports medicine. Jul2009;37(7):1417-1424. 30. U H. Medline Plus: Drugs, Supplements & Herbal Information 08/15/2014; http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/meds/a681 004.html. Accessed 2/3/15. 31. Hawker GA, Mian S, Kendzerska T, French M. Measures of adult pain: Visual Analog Scale for Pain (VAS Pain), Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS Pain), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPGS), Short Form-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS), and Measure oflntermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain (ICOAP). Arthritis care & research. Nov 2011 ;63 Suppl 11 :S240-252. 32. Spadoni GF, Stratford PW, Solomon PE, Wishart LR. The evaluation of change in pain intensity: a comparison of the P4 and single-item numeric pain rating scales. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. Apr 2004;34(4): 187-193. 40 33. Hislop HAD, Brown M. Daniel's and Worthingham's Muscle TestingTechniques of manual Examination and Performance Testing. 9th edition. St. Louis Missouri: Elsevier Saunders. 2014. 34. Cuthbert SC, Goodheart GJ, Jr. On the reliability and validity of manual muscle testing: a literature review. Chiropractic & osteopathy. 2007;15:4. 35. Colaco J DN, Karmacharya N, Holbein-Jenny M. Interrater reliability and validity of ober's, noble compression, and modified thomas tests. Physical therapy. 2002: June 5-8, 2002. 36. Reese NB BW. Use of an inclinometer to measure flexibility of the iliotibial band using the Ober test and the modified Ober test: differences in magnitude and reliability of measurements. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. 2003 Jun;33(6):326-30. 37. Gose JC, Schweizer P. Iliotibial band tightness. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. 1989;10(10):399-407. 38. Whatman C, Hume P, Hing W. The reliability and validity of physiotherapist visual rating of dynamic pelvis and knee alignment in young athletes. Physical therapy in sport : official journal of the Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Sports Medicine. Aug 20 13; 14(3): 168-174. 39. Maclachlan L, White SG, Reid D. Observer Rating Versus Three-Dimensional Motion Analysis of Lower Extremity Kinematics during Functional Screening Tests: A Systematic Review. International journal of sports physical therapy. Aug 2015;10(4):482-492. 41 40. Binkley JM, Stratford PW, Lott SA, Riddle DL. The Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS): scale development, measurement properties, and clinical application. North American Orthopaedic Rehabilitation Research Network. Physical therapy. Apr 1999;79(4):371-383. 41. Kamper SJ, Maher CG, Mackay G. Global rating of change scales: a review of strengths and weaknesses and considerations for design. The Journal of manual & manipulative therapy. 2009;17(3):163-170. 42. Stephens B, Gross DP. The influence of a continuum of care model on the rehabilitation of compensation claimants with soft tissue disorders. Spine. Dec 1 2007;32(25):2898-2904. 43. Youdas JW, Krause DA, Hollman JH, Harmsen WS, Laskowski E. The influence of gender and age on hamstring muscle length in healthy adults. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. Apr 2005;35(4):246-252.