* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Reactions to resin-based dental materials in patients

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

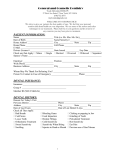

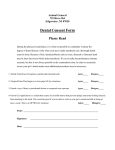

Contact Dermatitis 2009: 61: 313–319 Printed in Singapore. All rights reserved © 2009 John Wiley & Sons A/S CONTACT DERMATITIS Reactions to resin-based dental materials in patients–type, time to onset, duration, and consequence of the reaction ANDERS TILLBERG1 , BERNDT STENBERG2 AND ANDERS BERGLUND3 1 Faculty of Medicine, Institute of Clinical Dentistry, University of Tromsø/Public Dental Service Competence Centre of Northern Norway, Tromsø, Norway, 2 Faculty of Medicine, Department of Public Health and Clinical Medicine, and 3 Faculty of Medicine, Department of Odontology, Umeå University, Umeå, Sweden Objective: The aim of the present study was to determine the types of side-effects occurring and for how long they lasted in a group of patients with side-effects assessed to be caused by resin-based materials. Methods: A total of 618 reports were received by the Swedish National Register of Side-Effects to Dental Materials, among which 36 were on patients with reactions assessed to be caused by resin-based restorative materials. The group examined consisted of 25 women and 11 men, with a mean age of 47.8 ± 15.6 years. A follow-up was done through a structured telephone interview. Results: The majority of symptoms were intra-oral or a combination of intra-oral and extra-oral symptoms that appeared within the first 24 hr after treatment. The most common adverse effects reported were skin problems, oral ulcers, and burning mouth. Within less than a week, the reactions had disappeared in 50% of the patients. Conclusion: Immediate reactions to resin-based materials were more prevalent than delayed allergic reactions, and the mechanism of the immediate reactions is probably non-allergic in most cases. There is a need for developing provocation tests to verify the association between the reaction and the material, and also to identify the offending component. Key words: adverse effects; allergy; dental materials; resin-based materials. © John Wiley & Sons A/S, 2009. Accepted for publication 29 April 2009 In recent years, both scientific institutions and the general public have shown great interest in the possible side-effects from a number of dental materials. The prevalence of side-effects from dental materials is considered to be low in relation to the vast number of dental treatments undertaken and vary with the type of treatment (1, 2). There is, however, a lack of data concerning the frequency and the type of such side-effects. The reporting schemes in Scandinavia present the best estimates, which suggest that some sort of adverse reaction may occur in 1 in 700 to 1 in 2600 dental procedures (3–6). Since the exact number of persons exposed is not known, the magnitude of reactions is difficult to estimate. Complexities in analysing the reports on sideeffects from dental materials have also undoubtedly contributed to the absence of reliable data concerning the frequency of side-effects. Epidemiological data suggest that the majority of side-effects from dental resins are allergic contact in nature (7). Among dental professionals, allergic contact dermatitis has been studied in a number of papers (8–11). However, published information on contact allergy in patients has mainly been based on case reports (12–18). In 1996, the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare established a register on the side-effects of dental materials where reports were received from dentists, dental hygienist, and physicians. Since the register is a compilation of information on many patients, it enables analysis on more than individual case reports. 314 TILLBERG ET AL. The aim of the present study was to describe the type and duration of side-effects that occurred as well as treatment and long-term consequences in a group of patients with side-effects assessed to be caused by resin-based materials for direct dental restorations. Contact Dermatitis 2009: 61: 313–319 Patch test Altogether eight patients had test according to the Dental (Chemotechnique® Diagnostics, www.chemotechnique.se) used clinics in Sweden. undergone patch Screening Series Vellinge, Sweden; at Dermatology Materials and Methods The Swedish Register of Side-Effects of Dental Materials The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfares Register of Side-Effects of Dental Materials was established in Sweden in 1996 to monitor and evaluate adverse reaction from dental materials. This register was set up in collaboration with Medical-Odontological faculty of the University of Umeå, Sweden. As a similar reporting procedure had been in function since 1993 at the University of Bergen, Norway (19, 20), the Swedish unit exchanged experiences with the Norwegian unit. The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfares Register of Side-Effects of Dental Materials was phased out in 2002. Selection of study objects A total of 618 reports were received by the National Register of Side-Effects from 1996 to 1999, among which 456 reports were on patients and 162 on dental practitioners. Among the patients, 15% reported complaints in connection with treatment with composite and bonding materials. Specialists from the Department of Dental Materials Science, Faculty of Odontology, Umeå University, evaluated the reported reactions in collaboration with medical experts from occupational and environmental medicine and dermatology. The connection between the material and the reaction was assessed as ‘Probable’, ‘Possible’, ‘Uncertain’, or ‘Unclassifiable’, depending on the probability of the relationship and on the quality of information submitted by the reporter. A report was classified as ‘Probable’ when the reaction was well known, the investigation of the patient was complete, and no alternative explanation was feasible. When the investigation was insufficient but the reaction was well known and a time correlation could be established between treatment and reaction, then the classification ‘Possible’ was used because a relation could not be excluded. The inclusion criteria for the patients participating in the study were that they should have: (1) reactions suspected to be caused by resin-based materials for direct dental restorations; (2) reactions that the Side-Effects Registers Expert group had assessed to be ‘Probable’ or ‘Possible’; and (3) reactions occurring during the years 1996–1999. Telephone interview The patients (n = 36) who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were examined via a telephone interview with pre-determined questions (Fact Box 1) developed in collaboration with the Side-Effect Registers Expert group. The mean follow-up time between the report to the register and the telephone interview was 17 months (range 4–32 months). All 36 patients participated in the telephone interview. Fact Box 1. The content of the questionnaire (telephone interview) Background variables Marital status, number of children, education, type of work, contact with chemicals (epoxy and isocyanate), current employment situation, and work demands Remaining problems (symptoms) at follow-up Intra-oral symptoms: e.g. burning mouth, dry mouth, increased salivation, taste disorder, pain from temporomandibular joint, and stiffness/ numbness General symptoms: e.g. fatigue, headache, nausea, anxiety, depression, sleeping problems, vertigo, eye symptoms, skin symptoms, circulatory symptoms, and muscular and joint problems Consequences for the future Dental treatment, avoidance of plastics, etc. Consequences for work-related issues Stopped working, change of working capacity (work hours, sick leave, disability pension, early retirement pension) Diseases of importance for the patients’ symptoms Asthma, hay fever, eczema, and atopy Reactions in connection with replacement Type of reaction Examination performed by Dentists, medical doctor (general practioner or specialist), complimentary care Action taken due to symptoms No action, removal of dental restorations, and medication Contact Dermatitis 2009: 61: 313–319 REACTIONS TO RESIN-BASED DENTAL MATERIALS Ethical considerations The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine and Odontology, Umeå University. Information obtained from the register with complimentary addition through the telephone interview Time between treatment and symptom alleviation. The reactions disappeared within less than a week for more than half of the patients. In 25% of the patients, the symptoms remaining after 18 months (Table 4) were in all cases local, e.g. irritation and ulcers, unspecified intra-oral problems; pain from the gingiva that spread up through the nostrils; blisters on the tongue and lips; difficulties in eating and swallowing due to blisters and a stinging, burning sensation intra-orally. Consequences of the reactions. In 12 cases, the reported reactions have not had any consequences, but in 11 cases the patients had avoided restoring their teeth again with the same material. Furthermore, in eight cases, the patients had the material removed while four of the patients had not dared to go to the dentist after the reaction, which took place more than 1 year before the telephone interview. In one case, the patient had visited the dentist but did not allow the dentist to restore her cavities because she was afraid of new reactions. History of atopy and reported health problems. Three patients had had a test-verified atopic illness. Eight patients had or have had asthma before the reported reactions, and six patients had had hay fever. One patient had suffered food allergy caused by milk, egg fish, and hazelnuts. Ten of the patients reported that they had had eczema, six of them had undergone a patch test that verified contact allergy (not to resin-based materials) before the reported reaction. The allergens were nickel, chromate, and gold. Affection of the working capacity. In 26 cases, the patients were fully capable of working. However, in one case, the patient stated that he had been incapable of working for 9 months due to intraoral problems, e.g. burning mouth and ulcers that he related to his dental restorative material. In another case, a dental assistant was unable to work since she could not stay in the dental clinic mainly due to respiratory problems. A further 5 of the patients were senior citizens and 3 were prematurely retired because of disabilities unrelated to their dental materials. Sick leave related to dental materials. Of the 36 patients studied, 30 had not been on any sick leave due to the reactions. Three patients had been on sick leave for 2 weeks or less and a further three between 9 and 28 months. One of the patients was still on sick leave after 28 months due to difficulties in eating and swallowing. None of the 36 patients had been forced to retire prematurely because of the reported health problems. Results Information obtained from the register The group interviewed consisted of 25 women and 11 men, with a mean age of 47.8 ± 15.6 years (range 8–73). The connection between the material and the reaction was assessed by the Side-Effect Registers Expert group as ‘Probable’ in 13 patients and as ‘Possible’ in 23 patients. The most frequently reported materials suspected to be causing the reactions are listed in Table 1. The types of the symptoms and signs, and time between treatment and reactions The locations of the symptoms experienced by the patients together with the point of time of the first appearance of the symptoms are given in Fig. 1. Among those cases with intra-oral symptoms and signs, necrosis of the oral mucosa and a stinging, burning sensation in mouth were most frequently reported. Among the extra-oral symptoms and signs, skin reactions, e.g. rash and itching, were reported in 10 cases (Table 2). Most of the reactions (83%, n = 30) occurred within the first 24 hr after treatment of which almost two-third of the cases (n = 19) reacted during dental treatment (Fig. 1). A patient who had an immediate skin reaction after exposure to a temporary crown and bridge material is shown in Fig. 2. Action taken due to symptoms In most of the cases, no action was taken due to the symptoms (Table 3). Table 1. Materials suspected to cause the reactions Reported material n Primer, bonding, and composite resin Primer and bonding Primer Composite resin Composite cement for crown and bridges Etching gel Composite resin and amalgam Fluoride varnish, etching gel, and fissure sealant Primer, bonding, composite, and temporary cement Material for temporary crowns 14 12 1 1 2 2 1 1 1 1 More than one material is reported. 315 316 TILLBERG ET AL. Contact Dermatitis 2009: 61: 313–319 Fig. 1. Distribution of 36 patients stratified by the location of symptoms, time to onset of the symptoms, and result of patch test (Dental Screening Series, Sweden). Table 2. Type of symptoms and signs Symptom Intra oral Intra-oral sores Burning mouth Necrosis of the oral mucosa Swelling of the lips, oral cavity, and throat Extra oral Skin problem (rash and itching) Swelling of the face Extra-oral symptoms, not mentioned above* Asthmatic reactions Extra-oral sores n 7 7 5 4 10 7 5 4 2 More than one symptom is reported. Fig. 2. A patient who has just received a temporary bridge. Urticaria occurred on her arms and neck. Work-related exposures to chemicals. Seven of the patients examined reported that they were, or had been, occupationally exposed to chemicals in acrylates. The chemicals were, among others, developing liquids for photographs and plastics used to cover pictures, epoxy resins for sealing floors, composite resins, and solvents in dental clinics. Three of ∗ Headache, anxiety, difficulties in concentrating, vertigo, fatigue, palpitation, pain from muscles and joints. the patients reported that they were working with acrylates; a printmaker, a painter, and a dental assistant, whereas two of the patients reported that they were working with epoxy resin; a painter and a construction worker. The latter was tested and not found to be allergic to epoxy resin. Referrals or treatment after the reported reaction. Dentists had examined 5 of the patients, and Contact Dermatitis 2009: 61: 313–319 REACTIONS TO RESIN-BASED DENTAL MATERIALS Table 3. Action taken due to symptoms (n = 36) bias, which may either enhance or impair the recall of memory. However, self-generated information will be better remembered than, e.g. information that is simply readable, in cognitive science this is referred to the so-called generation effect. Therefore, the information obtained from the register combined with the information from the telephone interview will give a sufficient description of the patients’ situation. Methacrylic compounds are nowadays widely used in restorative dentistry, and composite resin restorations have almost completely replaced by amalgam fillings in Scandinavia (7). The acrylic content of dental composites poses a risk for adverse reactions. Although the quantities of the substances released are probably too small to cause systemic reactions, local skin or mucosal reactions may arise from direct contact with dental composites (21). It is often difficult to assess side-effects since the quality of the information in the material safety data sheet (MSDS) is often insufficient and may in some cases be incorrect (22–25). Moreover, MSDS do not need to specify components in low concentrations, which could be relevant to, e.g. allergic reactions. It has been suggested that a more stringent control of the risks with dental materials would be of importance from the patients’ and dental practioners’ point of view (26). Documented incidents of adverse reactions in patients caused by resin-based materials in dentistry are quite rare, despite of their extensive use. Underreporting is suspected to be high (27) which in turn leads to incidence figures that are unreliable. The problem has been recognized by van Noort et al. (27) who suggested that a pro-active reporting system should be established even if it takes time to generate useful information. When side-effects of dental materials are discussed, it must be clear whether they refer to patients or to dental practitioners. In a report from the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfares Register of Side-Effects from Dental Materials, it was reported that patients and dental practitioners reacted to different dental materials (28). A conceivable explanation for this is that the exposure is different between the groups. The practitioners are handling the materials when they are in their most reactive phase, whereas the patients often are exposed to set materials. Moreover, the relevance of a positive patch-test reaction to a substance in the dental screening series is not always easy to assess, and the symptoms might also be caused by other sources than dental materials. In addition to the dental screening series, tests with other substances must be considered for testing. In the present study, 13 reports dealt with primer and bonding, non-cured products that in in vitro Action taken n No treatment Removal of dental materials Corticosteroid treatment (one topical and three systemic) Antihistamine tablets Chlorhexidine (mouth rinse) Stopped working (dental nurse) Attended to hospital 19 8 4 2 1 1 1 Table 4. Time between treatment and symptom alleviation (n = 36) Time n Disappeared in less than a week after treatment Disappeared between 1 and 2 weeks after treatment Symptom still present after 18 months 19 8 9 specialists within medicine had examined 8 of the patients. Eight patients had been patch tested (Fig. 1). Furthermore, only 3 patients showed allergic type IV reactions to resin-based materials (1, non-rigid plastic; 2, methylmethacrylate, ethylenglycol dimethacrylate, hydroxyethyl methacrylate, dimethylaminoethyl methacrylate, and tethrahydrofurfuryl methacrylate; 3, methylmethacrylate). One of the 36 patients had been seeking treatment within the field of ‘alternative medicine’. Discussion In the present study, it was found that the majority of symptoms suspected to have been caused by resin-based materials were intra-oral or a combination of intra-oral and extra-oral symptoms that appeared within the first 24 hr after treatment. The most common adverse effects reported were skin problems, oral ulcers, and burning mouth. Within less than a week, the reactions disappeared in half of the patients, and in an equal number of patients no actions were taken due to the symptoms. Four of the patients had avoided visiting the dentist again after the reaction. This study was relatively extensive in comparison to earlier studies that were mainly based on case reports. The consistency in the answers to the telephone interviews is considered to be high since a protocol with pre-determined questions was used for all patients. The majority of symptoms appeared during treatment or at least within the first day, which indicates the need for new examination routines. However, it would have been desirable if all patients had been examined by a specialist in dermatology, which would have increased the credibility of the information given by the patients. The follow-up time between the reported symptoms and telephone interview must be taken under consideration because it might have introduced memory 317 318 TILLBERG ET AL. studies (29, 30) have shown to have a cytotoxic potential. Lönnroth et al. (30) have shown that the liquid component in resin products has a strong irritation capacity. Most of these reactions can be avoided by observing precautions such as following safe handling procedures and practices for dental practitioners that handle non-cured polymers manually (17). The most common adverse effects reported were skin problems and contact dermatitis, which is in line with earlier findings (7). In the present study, the most frequent oral manifestations included intraoral ulcers, swollen lips, and respiratory reactions such as swollen throat and asthma; the latter also has been reported to be common among dental practitioners (31). Burning mouth was reported in 20% of the patients (n = 7) but the role of contact allergy in the pathogenesis of burning mouth syndrome is unclear (32). The aetiology of burning mouth has also been suggested to be multifactorial with several local and systemic aetiological factors such as xerostomia, iron deficiency, lack of B-vitamins, and diabetes. Pharmaceuticals, e.g. levothyroxin and antihypertensive drugs, can also be associated with burning mouth (33, 34). Furthermore, depression and anxiety have frequently been reported among patients with burning mouth, which indicates that psychosomatic components may be involved (33, 35). Dental treatment involves the use of a wide range of materials. There are different clinical presentations of contact allergy to dental materials intra-orally but this entity is still not fully understood (36). Moreover, psychological stress has been reported to have a negative effect on wound healing of the oral mucosa which supports the idea that psychological strain plays an important role as an aetiological factor in the reactions of the oral mucosa (37, 38). Seven patients in the present study reported a work-related exposure to plastic before the symptoms appeared. Since none of these patients were verified as allergic to plastic, it is not likely that this exposure could explain the patients’ symptoms. Case reports (15–17) have shown that most reactions occurred during or close after insertion of the dental filling material. Almost 90% of the patient in the present study reported a similar reaction pattern. An immediate reaction is usually a type I reaction if the reaction is confirmed as allergic. Normally, the allergen is a protein/polypeptide like those found in latex products. This type of reaction affects above all atopic patients. Atopic patients were not over-represented among those with immediate reactions, and proteins are not a part of the content in composites. This observation indicates a non-allergic background for the reactions. There Contact Dermatitis 2009: 61: 313–319 are, however, exceptions from this ‘protein rule’. It has been reported that isocyanate and formaldehyde can cause IgE sensitization (39, 40), and this can occur also in previously non-atopic persons. It should be further investigated whether there are IgE-mediated reactions to composite materials. This should be investigated. More difficult but perhaps more urgent is the development of provocation tests to establish a relationship between the materials and reactions when it is of a non-allergic nature. Conclusion Immediate reactions to resin-based materials were more prevalent than delayed allergic reactions, and the mechanism of the immediate reactions is probably non-allergic in most cases. The mechanism of the immediate reactions should be further studied. Because of a lack of relevant provocation tests, we still have had great difficulties in verifying the association between the reaction and the material and also to identify the offending component when the mechanism is non-allergic. This is an important future research issue. References 1. Hensten-Pettersen A. Skin and mucosal reactions associated with dental materials. Eur J Oral Sci 1998: 106: 707–712. 2. Mjör I A. Biological side effects to materials used in dentistry. J R Coll Surg Edinb 1999: 44: 146–149. 3. Kallus T, Mjor I A. Incidence of adverse effects of dental materials. Scand J Dent Res 1991: 99: 236–240. 4. Jacobsen N, Aasenden R, Hensten-Pettersen A. Occupational health complaints and adverse reactions as perceived by personnel in public dentistry. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1990: 19: 155–159. 5. Jacobsen N, Hensten-Pettersen A. Occupational health problems and adverse patient reactions in orthodontics. Eur J Orthod 1989: 11: 254–264. 6. Jacobsen N, Hensten-Pettersen A. Occupational health problems and adverse patient reactions in periodontics. J Clin Periodontol 1989: 16: 428–433. 7. Kanerva L, Alanko K, Estlander T, Jolanki R, Lahtinen A, Savela A. Statistics of occupational contact dermatitis from (meth)acrylates in dental personnel. Contact Dermatitis 2000: 42: 175–177. 8. Rustemeyer T, Frosch P J. Occupational skin diseases in dental laboratory technicians. (I). Clinical picture and causative factors. Contact Dermatitis 1996: 34: 125–133. 9. Wallenhammar L M, Ortengren U, Andreasson H, Barregard L, Bjorkner B, Karlsson S, Wrangsjo K, Meding B. Contact allergy and hand eczema in Swedish dentists. Contact Dermatitis 2000: 43: 192–199. 10. Geukens S, Goossens A. Occupational contact allergy to (meth)acrylates. Contact Dermatitis 2001: 44: 153–159. 11. Wrangsjö K, Swartling C, Meding B. Occupational dermatitis in dental personnel: contact dermatitis with special reference to (meth)acrylates in 174 patients. Contact Dermatitis 2001: 45: 158–163. 12. Carmichael A J, Gibson J J, Walls A W. Allergic contact dermatitis to bisphenol-A-glycidyldimethacrylate (BISGMA) dental resin associated with sensitivity to epoxy resin. Br Dent J 1997: 183: 297–298. Contact Dermatitis 2009: 61: 313–319 13. Kanerva L, Alanko K, Estlander T. Allergic contact gingivostomatitis from a temporary crown made of methacrylates and epoxy diacrylates. Allergy 1999: 54: 1316–1321. 14. Koutis D, Freeman S. Allergic contact stomatitis caused by acrylic monomer in a denture. Australas J Dermatol 2001: 42: 203–206. 15. Koch P. Allergic contact stomatitis from BISGMA and epoxy resins in dental bonding agents. Contact Dermatitis 2003: 49: 103–115. 16. Martin N, Bell H K, Longman L P, King C M. Orofacial reaction to methacrylates in dental materials: a clinical report. J Prosthet Dent 2003: 90: 225–227. 17. Tanoue N, Nagano D T, Matsamura H. Use of a lightpolymerized composite removable partial denture base for a patient hypersensitive to poly(methyl methacrylate), polysulfone, and polycarbonate: a clinical report. J Prosthet Dent 2005: 93: 17–20. 18. Connolly M, Shaw L, Hutchinson I, Ireland A J, Dunnill M G S, Sansom J E. Allergic contact dermatitis from bisphenol-A-glycidyldimethacrylate during application of orthodontic fixed appliance. Contact Dermatitis 2006: 55: 367–368. 19. Gjerdet N R. Reporting of adverse reactions to dental biomaterials. Criteria and preliminary results from the Norwegian registry. I: dental amalgam and alternative direct restorative materials. In: Red, Mj ør I A, Pakhomov G N (eds): Geneve, WHO, 1997: 141–148. 20. Gjerdet N R, Askevold E. National reporting of adverse reactions to dental materials. The Norwegian Registry (Abstract). J Dent Res 1998: 77: 1532. 21. Tang A T, Bjorkman L, Ekstrand J. New filling materials – an occupational health hazard. Ann R Australas Coll Dent Surg 2000: 15: 102–105. 22. Henriks-Eckerman M L, Kanerva L. Product analysis of acrylic resins compared to information given in material safety data sheets. Contact Dermatitis 1997: 36: 164–165. 23. Kanerva L, Henriks-Eckerman M L, Jolanki R, Estlander T. Plastics/acrylics: material safety data sheets need to be improved. Clin Dermatol 1997: 15: 533–546. 24. Henriks-Eckerman M L, Suuronen K, Jolanki R, Alanko K. Methacrylates in dental restorative materials. Contact Dermatitis 2004: 50: 233–237. 25. Keegel T, Saunders H, Lamontagne A D, Nixon R. Are material safety data sheets (MSDS) useful in the diagnosis and management of occupational contact dermatitis? Contact Dermatitis 2007: 57: 331–336. 26. Tillberg A, J ärvholm B, Berglund A. Risks with dental materials. Dent Mater 2008: 24: 940–943. 27. van Noort R, Gjerdet N, Schedle A, Bjorkman L, Berglund A. An overview of the current status of national reporting systems for adverse reactions to dental materials. J Dent 2004: 32: 351–358. 28. The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare: The National Register of Side-Effects of Dental Materials - REACTIONS TO RESIN-BASED DENTAL MATERIALS 29. 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 36. 37. 38. 39. 40. 319 Annual Report for 2001, [2002-125-6] Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen, 2002 (in Swedish). Dahl J E. Irritation of dental adhesive agents evaluated by the HET-CAM test. Toxicol In Vitro 1999: 13: 259–264. Lönnroth E C, Dahl J E, Shahnavaz H. Evaluation the potential occupational hazard of handling dental polymer products using the HET-CAM technique. Int J Occup Saf Ergon 1999: 5: 43–57. Piirilä P, Hodgson U, Estlander T, Keskinen H, Saalo A, Voutilainen R, Kanerva L. Occupational respiratory hypersensitivity in dental personnel. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2002: 4: 209–216. Eisen D, Eisenberg E. Oral lichen planus and the burning mouth syndrome. Is there a role for patch testing? Am J Contact Dermat 2000: 11: 111–114. Bergdahl M, Bergdahl J. Burning mouth syndrome: prevalence and associated factors. J Oral Pathol Med 1999: 28: 350–354. Scalla A, Checchi L, Montevecchi M, Marini I. Update on burning mouth syndrome: overview and patient management. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2003: 14: 275–291. Bergdahl J, Anneroth G, Perris H. Cognitive therapy in the treatment of patients with resistant burning mouth syndrome: a controlled study. J Oral Pathol Med 1995: 24: 213–215. De Rossi S, Greenberg M. Intraoral contact allergy: a literature review and case reports. J Am Dent Assoc 1998: 129: 1435–1441. Kiecolt-Glaser J K, Marucha P T, Malarkey W B, Mercado A M, Glaser R. Slowing of wound healing by psychological stress. Lancet 1995: 346: 1194–1196. Marucha P T, Kiecolt-Glaser J K, Favagehi M. Mucosal wound healing is impaired by examination stress. Psychosom Med 1998: 60: 362–365. Jones M G, Floyd A, Nouri-Aria K T et al. Is occupational asthma to diisocyanates a non-IgE-mediated disease? J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006: 117: 663–669. Wisnewski A V. Developments in laboratory diagnostics for isocyanate asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2007: 7: 138–145. Address: Anders Tillberg, DDS, PhD Faculty of Medicine Institute of Clinical Dentistry University of Tromsø 9018 Tromsø Norway Tel: +47 776 49131 Fax: +47 776 49101 e-mail: [email protected]