* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Why do some business relationships persist

Predictive analytics wikipedia , lookup

Marketing plan wikipedia , lookup

Marketing ethics wikipedia , lookup

Social marketing wikipedia , lookup

Market environment wikipedia , lookup

High-commitment management wikipedia , lookup

Networks in marketing wikipedia , lookup

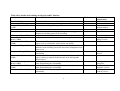

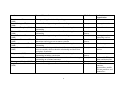

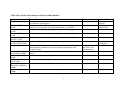

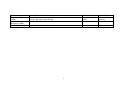

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Commerce - Papers (Archive) Faculty of Business 2012 Why do some business relationships persist despite dissatisfaction? a social exchange review Venkata K. Yanamandram University of Wollongong, [email protected] Lesley White Charles Sturt University Publication Details Yanamandram, V. K. & White, L. (2012). Why do some business relationships persist despite dissatisfaction? a social exchange review. Asia Pacific Management Review, 17 (3), 301-319. Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Why do some business relationships persist despite dissatisfaction? a social exchange review Abstract This paper reviews the relevant theories and marketing literature to develop a theoretical foundation for understanding the process and outcome of struggling business-to-business (B2B) customer relationships. Specifically, the paper provides a social exchange perspective of the factors that influence the likelihood of dissatisfied customers remaining in a present relationship by serving as deterrents to discontinuing the relationship. In doing so, the paper identifies the common features of, noteworthy differences among, and gaps in these theories. The paper also connects determinant factors to an outcome variable in order to explain what drives a customer in managing an unsatisfying business relationship, and therefore makes a conceptual contribution by proposing the effect of mediating variables, namely dependence and calculative commitment. Support for the hypothesised relationships would imply that specific investments are related to dependence or calculative commitment, which continues to play a role in generating customer outcomes. Keywords business, despite, do, dissatisfaction, social, exchange, review, relationships, why, persist Disciplines Business | Social and Behavioral Sciences Publication Details Yanamandram, V. K. & White, L. (2012). Why do some business relationships persist despite dissatisfaction? a social exchange review. Asia Pacific Management Review, 17 (3), 301-319. This journal article is available at Research Online: http://ro.uow.edu.au/commpapers/3186 Why do Some Business Relationships Persist Despite Dissatisfaction? A Social Exchange Review Venkata Yanamandram (Corresponding author) School of Management & Marketing, University of Wollongong, NSW 2522, Australia. Phone: +61 2 4221 3754 Fax: +61 2 4221 4154 Email: [email protected] Lesley White, Faculty of Business, Charles Sturt University, NSW 2795, Australia. Why do Some B2B Relationships Persist Despite Dissatisfaction? A Social Exchange Review Abstract This paper reviews the relevant theories and marketing literature to develop a theoretical foundation for understanding the process and outcome of struggling business-tobusiness (B2B) customer relationships. Specifically, the paper provides a social exchange perspective of the factors that influence the likelihood of dissatisfied customers remaining in a present relationship by serving as deterrents to discontinuing the relationship. In doing so, the paper identifies the common features of, noteworthy differences among, and gaps in these theories. The paper also connects determinant factors to an outcome variable in order to explain what drives a customer in managing an unsatisfying business relationship, and therefore makes a conceptual contribution by proposing the effect of mediating variables, namely dependence and calculative commitment. Support for the hypothesised relationships would imply that specific investments are related to dependence or calculative commitment, which continues to play a role in generating customer outcomes. Keywords: Social exchange theory, dissatisfied customer, business-to-business, services 1 1. Introduction Customers are commonly dissatisfied with the relationship they have with their service providers (Colgate and Lang, 2001), but how customers react to dissatisfaction is the crucial issue for marketing managers (Richins, 1987). Just as satisfied customers are not necessarily loyal (Rowley and Dawes, 2000), dissatisfied customers are not always disloyal (Hirschman, 1970). This paper reviews the relevant theories and marketing literature to develop a theoretical foundation for understanding the process and outcome of struggling B2B customer relationships. Although previous research provides a foundation for understanding the development, defection and maintenance of sound relationships, only limited work exists on the continuation of troubled B2B relationships (Tahtinen and Vaaland, 2006). Scholars note that future research should examine reasons to remain in a B2B services context (Colgate et al., 2007) and also explore the impact of dissatisfaction on the effects of buyer entrapment in a business service context (Liu, 2006). Moreover, no research has hitherto proposed mediating factors under the condition of dissatisfaction in the B2B services sector. The literature argues that the alternative outcomes of a customer either ending or continuing a struggling relationship not only depend on the determinant factors or switching barriers, but also on the essential nature of the relationship (Tuominen and Kettunen, 2003). This paper makes three contributions to marketing theory on why dissatisfied customers stay in a relationship. First, the paper provides a social exchange perspective of the factors that serve as deterrents to discontinuing the relationship. Second, the paper connects determinant factors to an outcome variable in order to explain what drives a customer in managing an unsatisfying customer relationship. Third, the paper focuses on a business services context, which is an under-researched area for this research problem. 2 The remainder of the paper is organised as follows. It begins with a review of the broad social exchange framework, followed by a discussion of the ‘investment model’ (Rusbult, 1980), the ‘model of cohesiveness’ (Levinger, 1979) and the ‘tripartite model of commitment’ (Johnson, 1973). These theories together incorporate important economic and social forces and also the fair/unfair distribution of the economic and social forces that guide the outcome of struggling relationships (Rusbult et al., 2006). The following section identifies the common features of, noteworthy differences among and gaps in these theories, and then delineates the choice of concepts to investigate the reasons that influence the likelihood of remaining in a present relationship by serving as deterrents to discontinuing the relationship. We then report key B2C (business-to-consumer) and B2B marketing studies in this area, synthesise the existing marketing literature and propose mediating hypotheses. The study concludes with discussion and suggestions for future research. 2. Literature Review 2.1 Social Exchange Framework Ouchi (1980) argues that parties engaged in exchange relationships can serve their long-range goals by looking beyond short-term, financially driven interests and considering the welfare of their exchange partners. In this regard, social exchange theories serve as one explanation for justifying exchange decisions, where parties evaluate relationships in a behavioural context for achieving the goals of the relationship (Thibaut and Kelley, 1959). A social exchange framework refers to any theoretical approach that focuses on the exchange of resources between or among people. Different exchange models emphasise some (but not all) of the four components of a social exchange framework: (1) balance of rewards and costs; (2) fairness or equity of the exchange; (3) comparison level; and (4) comparison 3 level for alternatives (Sprecher, 1998). The basic premise of the social exchange framework, and each of these theories, is that ‘each party in a dyad engages in a diverse set of exchanges to influence each other and attain the most favourable outcomes — that is, to maximise rewards and minimise costs’ (Byers and Wang, 2005, p. 204). Because these theories assess the nature of relationships by providing rules for evaluating the fair dispersal of economic and social value, the social exchange framework is important for understanding relationship development, relationship satisfaction and relationship stability (Rusbult et al., 2006). The following section reviews the social exchange theories relevant to the development of hypotheses in this current study. 2.1.1. Investment Model The investment model (eg, Rusbult, 1980) is based on the principles of interdependence theory (Thibaut and Kelley, 1959) and employs interdependence constructs namely satisfaction (which is influenced by the extent to which a partner fulfils the individual’s most important needs) and poor quality of alternatives, to analyse the tendency to persist in a relationship. Thus, interdependence theory identifies two means (satisfaction and quality of alternatives) through which dependence grows, where dependence refers to ‘the extent to which an individual “needs” a given relationship or relies uniquely on the relationship for attaining desired outcomes’ (Rusbult et al., 2006, p. 618). However, there is added component build into the investment model. Specifically, the model argues that satisfaction and quality of alternatives do not fully explain dependence, and it accounts for the development of dependence and commitment in two respects. First, it asserts that dependence is influenced by satisfaction, quality of alternatives and investment size. Investments enhance dependence because the act of investment increases the costs of ending a relationship, in that defecting would mean leaving behind cumulative investment, thus serving as a powerful psychological inducement to persist (Rusbult et al., 2006). Dependence describes the additive 4 effects of wanting to persist (feeling satisfied), needing to persist (having high investments) and having no choice but to persist (possessing poor alternatives) (Rusbult et al., 2006). Second, the model suggests that commitment emerges as a consequence of increasing dependence. Ultimately, an individual’s decision to remain in or terminate a relationship is most directly influenced by feelings of commitment, which is a subjective state that includes both cognitive and emotional components, and directly influences a wide range of behaviours in an ongoing relationship, and also summarises the nature of an individual’s dependence on a partner (Rusbult et al., 2006). The model further suggests that feelings of commitment are influenced by positive forces such as strong satisfaction, which make the individual want a relationship more, and also by negative forces, such as investing important resources. 2.1.2. Levinger’s Model of Cohesiveness The model of cohesiveness (Levinger, 1979) defines cohesiveness as an individual’s tie, bond or union in a relationship, and posits that the durability of a personal relationship depends on three broad types of forces: (1) current attractions, or the forces that drive individuals toward a relationship, (2) alternative attractions, or the forces that pull individuals away from their relationship and (3) barriers, or the forces that influence the likelihood of remaining in a present relationship by serving as deterrents to discontinuing the relationship, even when attraction forces reduce or cease to exist. The three broad types of forces are assumed to exert independent effects on cohesiveness and probability of persisting in a relationship (Rusbult et al., 2006). Thus, according to the model, a greater level of cohesiveness will result from a high level of attraction, a high level of barriers and a low level of alternative attractions. 5 2.1.3. Johnson’s Tripartite Model of Commitment The tripartite model of commitment (Johnson, 1973) considers commitment as a motivation to continue in a personal relationship. The model focuses on people making decisions and acting within situational opportunities and constraints, which are in turn shaped by larger-scale structural arrangements. Specifically, the model identifies three bases of commitment: (1) personal or ‘want to’ commitment, (2) moral or ‘ought to’ commitment and (3) structural or ‘have to’ commitment. Personal commitment represents a person’s desire and choice to stay in a relationship, and results from positive attitude towards ones’ partner, positive attitude toward the relationship, and relational identity or the extent to which the relationship is part of one’s self-identity. Moral commitment represents a felt obligation to remain in a relationship, and results from the moral obligation not to end the relationship, the sense of personal obligation to one’s partner, and the need to maintain consistency in one’s beliefs and cultural values. Structural commitment represents a feeling that one must remain in the relationship, and results from the unavailability of or relative unattractiveness of available alternatives, social pressure such as their network not approving of relationship dissolution, the difficulty of processes necessary to end the relationship, and irretrievable investments, such as expenditures of resources and/or effort, time, sacrifice and pledges. The model argues that when low levels of personal and moral commitments are present, the effect of structural commitment will become more prominent and will contribute to a sense of being entrapped in the relationship. Consequently, a partner will feel constrained by the costs of dissolution to stay. The following section reviews the common features of, noteworthy differences among, and gaps in the most prominent extant theories of commitment reviewed in this section. 6 3. Comparison of Theoretical Models The models proposed by Levinger, Rusbult and Johnson share four common features (Rusbult et al., 2006). First, all three models directly or indirectly consider the positive forces that induce an individual into a relationship. These positive forces are termed ‘attraction’ in Levinger’s model, ‘satisfaction’ in Rusbult’s and ‘personal commitment’ in Johnson’s. Second, all three models consider investments that bind an individual to a relationship. These forces are termed ‘barriers’ (Levinger), ‘investment size’ (Rusbult) and ‘irretrievable investments’ (Johnson). Third, all three models consider alternative quality. These forces are termed ‘alternative attractions’ (Levinger), ‘quality of alternatives’ (Rusbult) and ‘availability of or ‘attractiveness of available alternatives’, although presented as a dimension of structural commitment (Johnson). Fourth, all three models propose that the net outcome of factors promoting stability is to generate increased motivation to continue. This motivation is termed ‘cohesiveness’ (Levinger), ‘commitment’ (Rusbult) and ‘motivation to continue’ (Johnson). The three theories also attempt to explain ‘unjustified persistence or the tendency to remain involved in a relationship that is not particularly satisfying’ (Rusbult et al., 2006, p. 616). However, the three models differ in how they categorise the variables that promote commitment (Rusbult et al., 2006). For example, while Johnson’s model suggests that social pressure, termination procedures, irretrievable investments and potential alternatives are components of structural commitment, Levinger considers social pressure, termination procedures and irretrievable investments as components of barriers. Rusbult regards social pressure, termination procedures and irretrievable investments as part of investments. With respect to alternatives of attractiveness, both Levinger and Rusbult deem alternatives to be a separate force, while Johnson considers alternatives to be part of structural commitment. Each of the three models has some limitations (Rusbult et al., 2006). Levinger’s model, developed as an integrative tool to explain commonalities across diverse findings such 7 as attractions, alternative attractions and barriers, advances no instrument to measure model constructs. Johnson’s model distinguishes between different types of commitment, but does not provide clear operational definitions of constructs, and presents no overall measure of commitment. Several gaps in Rusbult’s investment model underpin this current research’s investigation. First, according to the model, commitment is the primary force in relationships. Drigotas and Rusbult (1992, p. 62) argue that the emphasis on commitment ‘served to deemphasize the original interdependence construct for predicting persistence in struggling relationships, namely the degree of dependence on a relationship ― dissatisfying as it is, the relationship may nevertheless fulfil important needs that cannot be fulfilled in alternative relationships’. Thus, researchers using the investment model to explain persistence in dissatisfying relationships should include both dependence and commitment. Drigotas and Rusbult (1992) propose a model of break-up decisions extending interdependence theory, and find support for several relationships: (1) dependence is a primary determinant of commitment, (2) commitment mediates the relationship between dependence and decisions to remain and (3) commitment mediates the relationship between other features of the relationship and stay-leave decisions. Second, empirical work that uses the investment model supports the claim that persistence in struggling relationships is partially attributable to poor alternatives and high investments (Rusbult and Martz, 1995). This suggests that poor alternatives and high investment may better explain a constraint-based component of commitment, rather than using a global construct of commitment, which Rusbult, Martz and Agnew (1998) define as ‘intent to persist in a relationship, including… feelings of psychological attachment’ (p. 359). The investments described in the investment model are similar to the relationshipspecific investments (RSIs) proposed in B2B relationships (Williamson, 1985). Evidence 8 exists that RSIs can be made at both the inter-organisational level and interpersonal levels — usually termed ‘switching costs’ and ‘interpersonal relationships’ respectively (Wathne et al., 2001). Switching costs arise from organisational-level investments in transaction-specific assets (Williamson, 1985); while interpersonal relationships derive from an individual’s investment in social capital (Coleman, 1988). Thus, when examining investments in business exchange relationships, Rusbult’s investment concept is represented by switching costs and interpersonal relationships. Regarding commitment, Johnson (1973) refers to structural commitment as the feeling that one must remain in the relationship, suggesting that it is a constraint-based commitment. The marketing literature also discusses several constraintbased forms of commitment, including viewing commitment as entirely calculative (eg., Geyskens, Steenkamp and Scheer, 1996; Gilliland and Bello, 2002). Overall, by adapting the social exchange framework to business exchange relationships, the constructs of attractiveness of alternatives, investments at the interorganisational and at the interpersonal level (namely switching costs and interpersonal relationships respectively) hold the most promise in explaining dependence and calculative commitment (Rusbult et al., 2006). These constructs influence the likelihood of remaining in a present relationship (repurchase intentions) by serving as deterrents to discontinuing the relationship. In order to confine its scope, this paper only proposes the mediating relationships between the determinant factors and behavioural outcomes. The next section reviews the key B2C and B2B empirical studies on relationship ending and staying in the marketing literature. 4. Empirical Studies on Relationship Ending and Staying Insert Table 1 here Insert Table 2 here 9 Tables 1 and 2 report the key B2C and B2B marketing studies on relationship ending and staying, which focus on the process or behaviours associated with relationship ending/switching; the factors that influence ending/switching behaviour; and the factors that influence the likelihood of remaining in a present relationship by serving as deterrents to discontinuing the relationship. The studies provide evidence that dissatisfaction arising from service failures or with the quality of service outcome or interaction, acts as a breakdown trigger (Roos, 1999) or a predisposing factor (Halinen and Tahtinen, 2002) and provokes a change in a customer’s attitude towards the switching (Bansal and Taylor, 1999). This alters the current state of the relationship (Anton, Camarero and Carrero, 2007) and initiates the dissolution process (Coulter and Ligas, 2001). During the dissolution process, there may be a temporary or permanent, fading, in the relationship strength between the customer and the service provider, where the outcome of the process may be unknown (Tuominen and Kettunen, 2003). However, the dissolution process includes several stages, which may act as critical decisive moments, because the customer firm can use a voice strategy including complaining and negotiating with its partner in order to restore the relationship (Alajoutsijarvi, Moller and Tahtinen, 2000; Halinen and Vaaland, 2002). The decision to delay or stop the ending process may further depend on swaying factors (Roos, 1999), mooring variables (Bansal, Taylor and James, 2005), attenuating factors (Tahtinen and Vaaland, 2006) or switching barriers (Burnham, Frels and Mahajan, 2003; Colgate and Lang, 2001; Colgate et al., 2007; Jones, Mothersbaugh and Beatty, 2002; Panther and Farquhar, 2004). These variables, if found to be ‘potent enough’ (Colgate et al., 2007, p. 212), will influence the likelihood of remaining in a present relationship by serving as deterrents to discontinuing the relationship. Conversely, if they are not potent enough, the customer may consider leaving the service provider (Bansal, Taylor and James, 2005), or actually leave (Keaveney, 1995). 10 Studies that have investigated deterrents to discontinuing the relationship, with the exception of Colgate and Lang (2001) and Colgate et al. (2007), examine determinant factors or switching barriers predicatively − by asking customers to consider dropping their service provider instead of an actual switching consideration. Therefore, investigating a group of customers (namely stayers) who have considered switching, but decide to stay with their service providers, would offer ‘insight into true behaviour rather than predicted behaviour’ (Colgate et al., 2007, p. 211). Colgate et al. (2007) examined stayers who had recently considered switching their service provider, but ultimately decided to stay. However, their investigation was in a B2C services context, and their sample also included customers who were comfortable and/or satisfied with their current provider, although whether those customers were comfortable and/or satisfied as a consequence of service recovery or otherwise is unknown. Thus, a gap exists in the research: to investigate the reasons customers stay amongst dissatisfied complaining customers who have considered switching — in a B2B services, rather than in a B2C services context. Among the studies that have considered deterrents to discontinuing the relationship, only a few investigated this subject in a B2B market. Extant examples have studied the effects of: (1) switching costs (Lam et al., 2004; Ping, 1993; Sengupta, Krapfel and Pusateri, 1997; Tahtinen and Vaaland, 2006; Wathne, Biong and Heide, 2001); (2) interpersonal relationships (Tahtinen and Vaaland, 2006; Wathne, Biong and Heide, 2001); and (3) unattractiveness of alternative providers (Ping, 1993; Tahtinen and Vaaland, 2006); Of these, only Tahtinen and Vaaland (2006) examine ‘struggling’ business relationships. 5. Mediating Hypotheses The social exchange theories reviewed thus far provide a basis for proposing that dependence and/or calculative commitment mediate the effect of satisfaction, investments and 11 the attractiveness of alternatives on repurchase intentions. Since this research focuses on unsatisfactory relationships, it is only possible to extend mediating hypotheses between investments, attractiveness of alternatives and repurchase intentions. Regarding investments, the literature has found a significant association between switching costs and repurchase intentions/loyalty, in a B2C services context (Bansal and Taylor, 1999; Burnham, Frels and Mahajan, 2003; Jones, Mothersbaugh and Beatty, 2002); and in a B2B context (Lam et al., 2004; Wathne, Biong and Heide, 2001). Within the switching costs domain, the dimension of benefit-loss costs is consistently found to have a strong impact on behavioural/repurchase intentions, although the relationship between benefit-loss costs and repurchase intentions has only been investigated in a B2C services context (Jones, Mothersbaugh and Beatty, 2002; Patterson and Smith, 2003). Jones, Mothersbaugh and Beatty (2002) expected benefit-loss costs to be more strongly associated with repurchase intentions than are other switching costs, and found support for their hypothesis. Thus, given that the direct effect of benefit-loss costs on repurchase intentions are powerful in a B2C services context, it seems unlikely that dependence or calculative commitment should completely mediate the relationship between benefit-loss costs and repurchase intentions in a B2B services context either. The only study located that proposes mediating hypotheses between switching costs and repurchase intentions is Bansal, Irving and Taylor (2004), who found that calculative commitment partially mediated the relationship between switching costs and switching intentions in a B2C services context. This reasoning and associated evidence led to the following hypotheses: H1: Dependence partially mediates the relationship between benefit-loss costs and repurchase intentions. H2: Calculative commitment partially mediates the relationship between benefit-loss costs and repurchase intentions. 12 According to the investment model, commitment partially or wholly mediates the effects of investments on decisions to remain. Rusbult, Martz and Agnew (1998) operationalised investments as the perceived magnitude of the relationship assets that would be lost if the relationship were to be terminated. Therefore, according to the investment model, commitment partially or wholly mediates the effects of sunk costs on a decision to remain or leave. The consumer services marketing literature contains evidence on the direct effect of sunk costs on repurchase intentions in a B2C services context (Jones, Mothersbaugh and Beatty, 2002). Additionally, if investments in assets that are specific to a particular environment are considered important, and if losing those investments would have little value outside a particular relationship, then this should increase a customer’s dependence and a customer’s calculative commitment respectively, and these in turn should increase the customer’s repurchase intentions. Since a strong effect of sunk costs on repurchase intentions has not been demonstrated in a marketing context, the relationship between sunk costs and repurchase intentions could be argued to be completely mediated by either dependence or calculative commitment. This reasoning leads to the following hypotheses: H3: Dependence completely mediates the relationship between sunk costs and repurchase intentions. H4: Calculative commitment completely mediates the relationship between sunk costs and repurchase intentions. Regarding interpersonal relationships that are considered as investments at the interpersonal level (Wathne, Biong and Heide, 2001), a qualitative study found that a personal relationship was the primary motivation to stay in a business service relationship, even if strong reasons to seek another provider existed (Young and Denize, 1995). The present study 13 argues that interpersonal relationships are less important than switching costs in influencing dependence or calculative commitment, which suggests a weak effect. For example, researchers investigating transaction-specific assets argue that human asset specificity (relationship-specific investments at the interpersonal level) may originate in unconscious learning-by-doing processes, which are probably redeployable to alternative relationships after time. They thereby become general investments, and therefore, may have lesser impacts on perceived dependence than firm-level switching costs (Noorderhaven, Nooteboom and Berger, 1998). Similarly, evidence exists that social bonds have no influence on calculative commitment between customers and suppliers in complex buying situations (Han and Wilson, cited in Wilson, 1995) or in the B2B context (Cater and Zabkar, 2009), because a company can rarely justify bad decisions based on friendship between boundary-spanning personnel alone (Gounaris, 2005). Since mediating effects are typically proposed when evidence emerges of a relatively strong direct effect between a predictor variable and an outcome variable (Baron and Kenny, 1986), a mediating proposition is not offered regarding interpersonal relationships. Regarding attractiveness of alternatives, mixed results are evident across studies. For example, Jones, Mothersbaugh and Beatty (2000) found no significant association between attractiveness of alternatives and repurchase intentions when modelled with switching costs and interpersonal relationships. However, they did find that the relationship between attractiveness of alternatives and repurchase intentions was moderated by satisfaction. In contrast, Patterson and Smith (2003), in a B2C services context, found that the attractiveness of alternatives had a significant, though a small negative effect on behavioural intentions when satisfaction, interpersonal relationships and various switching costs were included in the model. Similarly, Bansal, Irving and Taylor (2004) and Bansal, Taylor and James (2005), in a B2C services context, found a significant relationship between attractiveness of alternatives 14 and switching intentions. In a B2B context, Ping (1993) found no significant association between attractiveness of alternatives and loyalty, but found a significant association between attractiveness of alternatives and intention to leave. In a subsequent study, Ping (1994) found that overall satisfaction moderates the association between attractiveness of alternatives and intention to leave. In view of the conflicting findings, and the fact that mediating effects are typically proposed when there is evidence of a relatively strong direct effect between a predictor variable and an outcome variable, we do not propose a mediating effect hypothesis between the attractiveness of alternatives and repurchase intentions. Figure 1 depicts the proposed model for establishing mediation, which involves four steps (Baron and Kenny, 1986). First, the independent variable must be significantly associated with the dependent variable. Second, the independent variable must be significantly associated with the presumed mediator. Third, the presumed mediator must be significantly associated with the dependent variable. Finally, the previously significant relationship between the independent variable and dependent variables should become non-significant when the mediator is included; if it does, then the direct effect is said to be fully mediated. However, if the effect of the previously significant relationship between the independent variable and the dependent variable in only reduced, and not zero, when the mediator is included, then the direct effect is said to be partially mediated. This current study proposes mediation relationships only. It is possible to extend hypotheses between other variables of the social exchange framework (independent variables namely interpersonal relationships and attractiveness of alternatives, and dependent variables namely dependence and calculative commitment); however, these are not the focus of this current paper. 15 6. Discussion Support for the hypothesised relationships would imply that the potential loss of special privileges if the customer were to switch from their current service provider is related to a feeling of dependence on the service provider. This degree of dependence on the relationship continues to play a role in generating customer outcomes. The potential loss of special privileges also results in calculative commitment, which influences a customer to intend to continue repurchasing services. The mediation mechanisms imply that sunk costs are related to dependence or calculative commitment more than repurchase intentions, and that dependence or calculative commitment continues to play a role in generating customer outcomes. An understanding of the mediating function of the key variables of dependence and calculative commitment can also be advantageous for service managers in inducing dissatisfied customers to stay. For example, a service provider might choose to foster customer retention by increasing various switching costs. However, a time lag persists between the introduction of these measures and the outcome. In the interim, service providers can monitor changes in customers’ dependence and calculative commitment — thus increasing managerial awareness of the reasons for continuing the relationship. However, service firms that retain dissatisfied customers may be encouraging the spread of negative word-of-mouth, who may become hostile, engaging in communication sabotage (Jones, Mothersbaugh and Beatty, 2000). While customers may repurchase services because of the perception that switching costs and resultant dependence and calculative commitment are high, offending service firms may not be insured against customer defection over the long-term. This is because the losses from service failures would be outweighed more heavily than the gains received during complaint-handling (Smith, Bolton and Wagner, 1999). From this point of view, dependence 16 may be experienced as one of the costs of participating in a particular relationship (Sabatelli and Shehan, 1993). Consequently, customers may wish to reduce their dependence on the service provider, unless a substantial recovery takes place, where equity and satisfaction are restored to their original levels. One solution to managing struggling customer relationships may be to adopt a strategic perspective on service failure management, because of its potential to contribute to firms’ learning at organisational levels (La and Kandampully, 2004). Such learning can not only be used to make improvements in the service firms’ outcome, procedural and interactional aspects of complaint handling, but also “to create a set of knowledge that can be used for…transformational change…, with the ultimate objective being to establishing a sustainable competitive advantage based on superior customer value” (La and Kandampully, 2004, p.392). By adopting a strategic perspective on service failure management, overall satisfaction regains the focus. Overall satisfaction, in turn, has a strong impact on customer retention and profitability (Oliver, 1997). 7. Conclusion and Future Research The literature suggests that switching barriers or factors play a major role in retaining customers. This research proposes that the alternative outcomes of a customer either ending or continuing a dissatisfactory relationship depend on the switching barriers or determinant factors, and also on the essential nature of the relationship, such as dependence or calculative commitment. Thus, this paper has considered the influence that complex relationships have in responding to struggling B-to-B service relationships, and has a laid a foundation for further research concerning the retention of dissatisfied customers. Future research could seek empirical support for the hypotheses presented here. In addition, scholars investigating customer retention note that further research is needed to 17 understand the moderating characteristics of relationships (for example, Homburg and Giering, 2001). One variable that future research could investigate is the moderating effect of the duration of the relationship. In turn, the effect this has on the effect that switching costs and commitment have on relationship outcomes may be of interest from a managerial perspective. For example, knowledge on how short- and long-term relationships differ could help managers to develop specific strategies for both relationship types (Verhoef, Franses and Hoekstra, 2002). 18 Table 1 Key Studies on Switching and Staying in B2C Markets Author Focus of Research Fornell (1992) Keaveney (1995) Colgate, Stewart and Kinsella (1996) Stewart (1998) Roos (1999) Coulter and Ligas (2000) Jones, Mothersbaugh and Beatty (2000) Ganesh, Arnold and Reynolds (2000) Colgate and Hedge (2001) Colgate and Lang (2001) Keaveney and Parthasarathy (2001) Jones, Motherbaugh and Beatty (2002) Burnham, Frels and Mahajan (2003) Patterson and Smith (2003) Method Factors that deter customers from discontinuing the relationship Critical incidents causing switching behaviour Reasons for switching service providers Survey Interviews Survey Process of customer exit Critical incident and critical path leading from the trigger of the incident to switching (process of switching) Stages in dissolution process Factors that deter customers from discontinuing the relationship Interviews Interviews Characterize differences between switchers and stayers in aspects such as satisfaction, involvement and loyalty Process of switching by examining the antecedents that influence both switching behaviour and formal complaints made prior to exit Factors that deterred customers from discontinuing the relationship Characterize differences between switchers and stayers with aspects relating to attitude, behavior and socio-demographic characteristics Various dimensions of switching costs that deterred customers from discontinuing the relationship Various dimensions of switching costs that deterred customers from discontinuing the relationship Factors that deterred customers from discontinuing the relationship 19 Interviews Survey Product/ Organisation Various services Various services Financial services (student market) Banking services Supermarket Interviews Various Banking and hair styling services Banking services Survey Banking services Survey Banking and insurance services Online services Survey Survey Survey Survey Banking and hairstylists Credit card and telephone services Travel agencies and medical services. Author Focus of Research Method Tuominen and Kettunen (2003) Bansal, Irving and Taylor (2004) Panther and Farquhar (2004) Phase preceding the relationship ending process Survey Product/ Organisation Airline services Factors influencing service provider switching Survey Auto repair services Factors that deterred customers from discontinuing the relationship Factors that deterred customers from discontinuing the relationship Factors influencing service provider switching Survey Financial services Interviews, Survey Survey Financial services Effects of customer satisfaction, relationship commitment dimensions and triggers on customer retention Factors that deterred customers from discontinuing the relationship Factors and mediating variables that influence switching with a focus on variables that weaken the relationship and those that precipitate dissolution Factors that deterred customers from discontinuing the relationship including satisfaction Effects of factors that deterred customers from discontinuing the relationship on relational outcomes Factors influencing service provider switching Factors influencing customer commitment Interviews, Survey Survey White and Yanamandram (2004) Bansal, Taylor and James (2005) Gustafsson, Johnson and Roos (2005) Vazquez-Carrasco and Foxall (2006) Anton, Camarero and Carrero (2007) Colgate et al. (2007) Jones et al. (2007) Wieringa and Verhoef (2007) Bügel, Buunk and Verhoef (2010) 20 Auto repair and hairstyling services Telecom. services Hairdressing Survey Automobile insurances services Interviews, Survey Survey Various services Survey Survey Banks, cable TV, phone and hairstylists. Energy services Banks, health insurance, supermarkets, mobile telecom providers and automotives. Table 2 Key Studies on Switching and Staying in B2B Markets Author Ping (1993) Heide and Weiss (1995) Young and Denize (1995) Ennew and Binks (1996) Sengupta, Krapfel and Pusateri (1997) Gronhaug, Henjesand and Koveland (1999) Haugland (1999) Alajoutsijarvi, Moller and Tahtinen (2000) Giller and Matear (2001) Wathne, Biong and Heide (2001) Lam, Shankar, Erramilli and Murthy (2004) Tahtinen and Vaaland (2006) Focus of Research Antecedents and response intentions of hardware retailers when there are problems with suppliers Factors that influence whether buyers stay with an existing provider or switch to a new provider once the consideration set is formed Reasons for continuing relationships despite mistakes by suppliers Method Survey Interviews Product/Firm Hardware retailers Computer workstations Accountants Links between customer retention, defection, and service quality Survey Banks Factors that deter customers from discontinuing the relationship Interviews, Survey Various Reasons why long-term relationships fade away Case Study Factors that influence the duration of buyer–seller relationships by investigating the differences between ongoing relationships and terminated ones Communication strategies at a particular stage of the dissolution process Process of relationship ending Longitudinal Interviews and Questionnaires Case Study Furniture production Farmed salmon Various Case Study Various Determinants of switching Interviews Banking Antecedents of customer retention Survey Courier services Factors that deter customers from discontinuing the relationship Interviews Oil industry 21 Survey Author Tidstrom and Ahman (2006) Bogomolova and Romaniuk (2009) Yen and Horng (2010) Focus of Research Process of ending inter-organizational cooperation by identifying the reasons and stages of the ending Reasons for brand defection Method Longitudinal Case Study Interviews Product/Firm Construction industry Financial service Factors that drive switching intention Survey Electronics 22 Figure 1 Proposed Mediation Relationships Dependence Switching Costs (benefit-loss and sunk costs) REPURCHASE INTENTIONS Calculative Commitment References Alajoutsijärvi, K., Möller, K. Tähtinen, J. (2000) Beautiful exit: how to leave your business partner. European Journal of Marketing, 34(11/12), 1270-1289. Antón, C., Camarero, C., Carrero, M. (2007) The mediating effect of satisfaction on consumers’ switching intention. Psychology & Marketing, 24(6), 511-538. Austin, W.G. (1979) Justice, freedom, and self-interest in intergroup conflict. in Austin, W.G., Worchel, S. (eds). The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Brooks/Cole, Monterey, California. Bansal, H.S., Shirley F.T. (1999) The service provider switching model (SPSM). Journal of Service Research, 2(2), 200-218. Bansal, H.S., Irving, G., Taylor, S.F. (2004) A three-component model of customer commitment to service providers. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32(3), 234-50. Bansal, H.S., Taylor, S.F., James, Y. (2005) ‘Migrating’ to new service providers: toward a unifying framework of consumers’ switching behaviors. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 33(1), 96-115. Baron, R.M., Kenny, D.A. (1986) The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173-1182. Bogomolova, S., Romaniuk, J. (2009) Brand defection in a business-to-business financial service. Journal of Business Research, 62, 291-296. Bügel, M.S., Buunk, A.P., Verhoef, P.C. (2010) A comparison of customer commitment in five sectors using the psychological investment model. Journal of Relationship Marketing, 9, 229. Burnham, T.A., Frels, J.K., Mahajan, V. (2003) Consumer switching costs: a typology, antecedents, and consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 31(2), 109-126. Byers, S.E., Wang, A. (2005) Understanding sexuality in close relationships from the social exchange perspective. in Harvey, J.H., Wenzel, A., Sprecher, S. (eds.). The Handbook of Sexuality in Close Relationships. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, New Jersey, 203-234. Cater, B., Zabkar, V. (2009) Antecedents and consequences of commitment in marketing research services: The client's perspective. Industrial Marketing Management, 38 (7), 785-797. Coleman, J.S. (1988) Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94(S1), 95-120. Colgate, M., Hedge, R. (2001) An investigation into the switching process in retail banking services. The International Journal of Bank Marketing, 19(5), 201-12. Colgate, M., Lang, B. (2001) Switching barriers in consumer markets: an investigation of the financial services industry. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 18(4), 332-47. Colgate, M., Norris, M. (2001) Developing a comprehensive picture of service failure. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 12(3/4), 215-34. Colgate, M., Stewart, K., Kinsella, R. (1995) Customer defection: a study of the student market in Ireland. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 14(8), 23-29. Colgate, M., Tong, V.T., Lee, C.K., Farley, J.U. (2007) Back from the brink: why customers stay. Journal of Service Research, 9(3), 211-28. Colwell, S.R., Hogarth-Scott, S. (2004) The effect of cognitive trust on hostage relationships. Journal of Services Marketing, 18(5), 384-394. Coulter, R., Ligas, M. (2000) The long good-bye: the dissolution of customer-service provider relationships. Psychology & Marketing, 17(8), 669-695. Cronin, J.J., Brady, M.K., Hult, G.T. (2000) Assessing the effects of quality, value and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. Journal of Retailing, 76(2), 193-218. Fornell, C. (1992) A national customer satisfaction barometer: the Swedish experience. Journal of Marketing, 56(1), 6-21. Drigotas, S.M., Rusbult, C.E. (1992) Should I stay or should I go?: a dependence model of breakups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62(1), 62-87. Ganesh, J., Arnold, M.J., Reynolds, K.E. (2000) Understanding the customer base of service providers: an examination of the differences between switchers and stayers. Journal of Marketing, 64(3), 65-87. Geyskens, I., Steenkamp, J., Scheer, L.K. (1996) The effects of trust and interdependence on relationship commitment. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 13(4), 303-317. Giller, C., Matear, S. (2000) The termination of interfirm relationships. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 15(2), 94-112. Gilliland, D.I., Bello, D.C. (2002) Two sides to attitudinal commitment: the effect of calculative and loyalty commitment on enforcement mechanisms in distribution channels. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 30(1), 24-43. Goodwin, C., Ross, I. (1992) Consumer responses to service failures: influence of procedural and interactional fairness perceptions. Journal of Business Research, 25(2), 149163. Gounaris, S.P. (2005) Trust and commitment influences on customer retention: insights from business-to-business services. Journal of Business Research, 58(2), 126-140. Grønhaug, K., Henjesand, I.J., Koveland, A. (1999) Fading relationships in buisness markets: an exploratory study, Journal of Strategic Marketing, 7(3), 175-190. Gustafsson, A., Johnson, M.D., Roos, I. (2005) The effects of customer satisfaction, relationship commitment dimensions, and triggers on customer retention. Journal of Marketing, 69(4), 210-218. Halinen, A., Tahtinen, J. (2002) A process theory of relationship ending. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 13(2), 163-180. Halinen, A., Tahtinen, J. (2002) A process theory of relationship ending. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 13(2), 163-180. Heide, J.B., Weiss, A.M. (1995) Vendor consideration and switching behavior for buyers in high-technology markets. Journal of Marketing, 59(3), 30-43. Hirschman, A.O. (1970) Exit, Voice and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations and States. Harvard University Press, Cambridge. Homburg, C., Furst, A. (2005) How organizational complaint handling drives customer loyalty: an analysis of the mechanistic and the organic approach. Journal of Marketing, 69(3), 95-114. Homburg, C., Giering, A. (2001) Personal characteristics as moderators of the relationship between customer satisfaction and loyalty: an empirical analysis. Psychology & Marketing, 18(1), 43-66. Johnson, M.P. (1973) Commitment: a conceptual structure and empirical application. Sociological Quarterly, 14(3), 395-406. Jones, M.A., Mothersbaugh, D.L., Beatty, S.E. (2000) Switching barriers and repurchase intentions in services. Journal of Retailing, 76(2), 259-274. Jones, M.A., Mothersbaugh, D.L., Beatty, S.E. (2002) Why customers stay: measuring the underlying dimensions of services switching costs and managing their differential strategic outcomes. Journal of Business Research, 55(6), 441-450. Jones, M.A., Reynolds, K.E., Mothersgbaugh, D.L., Beatty, S.E. (2007) The positive and negative effects of switching costs on relational outcomes. Journal of Service Research, 9(4), 335-355. Keaveney, S. (1995) Consumer switching behaviour in service industries: an exploratory study. Journal of Marketing, 59(2), 71-82. Keaveney, S., Parthasarathy, M. (2001) Customer switching behavior in online services: an exploratory study of the role of selected attitudinal, behavioral and demographic factors. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 29(4), 374-390. La, K., Kandampully, J. (2004) Market oriented learning and customer value enhancement through service recovery management, Managing Service Quality, 14(5), 390-401. Lam, S.Y., Shankar, V., Erramilli, M.K., Murthy, B. (2004) Customer value, satisfaction, loyalty, and switching costs: an illustration from a business-to-business service context. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32(3), 293-311. Lapidus, R.S., Pinkerton, L. (1995) Customer complaint situations: an equity theory perspective. Psychology & Marketing, 12(2), 105-122. Levinger, G. (1979) A social exchange view on the dissolution of pair relationships. in Burgess, R.L., Huston, T.L. (eds.). Social Exchange in Developing Relationships. Academic Press, New York, 169-193. Lind, E.A., Tyler, T.R. (1988) The Social Psychology of Procedural Justice. Plenum, New York. Liu, A.H. (2006) Customer value and switching costs in business services: developing exit barriers through strategic value management. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 21(1), 30-37. Masterson, S.S., Lewis, K., Goldman, B.M., Taylor, M.S. (2000) Integrating justice and social exchange: the differing effects of fair procedures and treatment of work relationships. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 738-748. Montgomery, B.M. (1993) Relationship maintenance versus relationship change: a dialectical dilemma. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 10(2), 205-223. Noorderhaven, N.G., Nooteboom, B., Berger, H. (1998) Determinants of perceived interfirm dependence in industrial supplier relations. Journal of Management and Governance, 2(3), 213-232. Oliver, R.L. (1997) Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer, Irwin/McGrawHill, New York. Ouchi, W.G. (1980) Markets, bureaucracies, and clans. Administrative Science Quarterly, 25(1), 129-141. Panther, T., Farquhar, J.D. (2004) Consumer responses to dissatisfaction with financial service providers: an exploration of why some stay while others switch. Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 8(4), 343-353. Patterson, P.G., Smith, T. (2003) A cross cultural study of switching barriers and propensity to stay with service providers. Journal of Retailing, 79(2), 107-120. Ping, R.A. (1993) The effects of satisfaction and structural constraints on retailer exiting, voice, loyalty, opportunism and neglect. Journal of Retailing, 69(3), 320-352. Ping, R.A. (1994) Does satisfaction moderate the association between alternative attractiveness and exit intention in a marketing channel?. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 22(4), 364-371. Richins, M.J. (1987) A multivariate analysis of responses to dissatisfaction. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 15(3), 24-31. Roos, I. (1999) Switching processes in customer relationships. Journal of Service Research, 2(1), 68-85. Rowley, J., Dawes, J. (2000) Disloyalty: a closer look at non-loyals. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 17(6), 538-547. Rusbult, C.E. (1980) Commitment and satisfaction in romantic associations: a test of the investment model. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 16(2), 172-186. Rusbult, C.E. Martz, J.M. (1995) Remaining in an abusive relationship: an investment model analysis of nonvoluntary commitment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21(6), 558-571. Rusbult, C.E., Coolsen, M.K., Kirchner, J.L., Clarke, J.A. (2006) Commitment. in Vangelisti, A.L., Perlman, D. (eds.). The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationships. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 615-636. Rusbult, C.E., Martz, J.M., Agnew, C.R. (1998) The investment model scale: measuring commitment level, satisfaction level, quality of alternatives, and investment size. Personal Relationships, 5(4), 357-391. Sengupta, S., Krapfel, R. Pusateri, M. (1997) Switching costs in key account relationships. The Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 17(4), 9-16. Sabatelli, R.M., Shehan, C. (1993) Exchange and resource theories”, in Boss, P., Doherty, W., LaRossa, R., Schuum, W., Steinmetz, S. (eds.), Sourcebook of Family Theories and Methods, Plenum Press, New York. Smith, A., Bolton, R., Wagner, J. (1999) A model of customer satisfaction with service encounters involving failure and recovery. Journal of Marketing Research, 36(3), 356-372. Sprecher, S. (1998) Social exchange theories and sexuality. The Journal of Sex Research, 35(1), 32-43. Stewart, K. (1998) An exploration of customer exit in retail banking. The International Journal of Bank Marketing, 16(1), 6-14. Tahtinen, J., Vaaland, T. (2006) Business relationships facing the end: why restore them?. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 21(1), 14-23. Tidstrom, A., Ahman, S. (2006) The process of ending inter-organizational cooperation, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 21(5), 281-290. Tax, S.S., Brown, S.W., Chandrashekaran, M. (1998) Customer evaluations of service complaint experiences: implications for relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 62(2), 60-76. Thibaut, J.W., Kelley, H.H. (1959) The Social Psychology of Groups. Wiley, New York. Tuominen, P., Kettunen, U. (2003) To fade or not to fade? That is the question in customer relationships, too. Managing Service Quality, 13(2), 112-123. Vazquez-Carrasco, R., Foxall, G.R. (2006) Positive vs. negative switching barriers: the influence of service consumers’ need for variety. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 5(4), 367-379. Verhoef, P.C., Franses, P.H., Hoekstra, J.C. (2002) The effect of relational constructs on customer referrals and number of services purchased from a multiservice provider: does age of relationship matter?. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 30(3), 202-216. Wathne, K.H., Biong, H., Heide, J.B. (2001) Choice of supplier in embedded markets: relationship and marketing program effects. Journal of Marketing, 65(2), 54-66. White, L., Yanamandram, V. (2004) Why customers stay: reasons and consequences of inertia in financial services. Managing Service Quality, 14(2/3), 183-194. Wieringa, J.E., Verhoef, P.C. (2007) Understanding customer switching behavior in a liberalizing service market. Journal of Service Research, 10(2), 174-186. Williamson, O.E. (1985) The Economic Institutions of Capitalism. Free Press, New York. Wilson, D.T. (1995) An integrated model of buyer-seller relationships. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23(4), 335-345. Yen, Y-X., Horng, D-J. (2010) Effects of satisfaction, trust and alternative attractiveness on switching intentions in industrial customers. International Journal of Management and Enterprise Development, 8(1), 82-101. Young, L., Denize, S. (1995) A concept of commitment: alternative views of relational continuity in business service relationships. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 10(5), 22-37.