* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Long-term mortality predictors in patients with chronic bifascicular

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

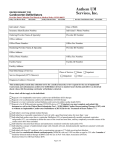

CLINICAL RESEARCH Europace (2009) 11, 1201–1207 doi:10.1093/europace/eup181 Electrophysiology and Ablation Long-term mortality predictors in patients with chronic bifascicular block Julio Marti-Almor*, Merce Cladellas, Victor Bazan, Carmen Altaba, Miguel Guijo, Joaquim Delclos, and Jordi Bruguera-Cortada Cardiology Department, Hospital del Mar, 25-29 Passeig Maritim, Barcelona 08003, Spain Received 15 April 2009; accepted after revision 10 June 2009; online publish-ahead-of-print 3 July 2009 To evaluate the long-term mortality rate and to determine independent mortality risk factors in patients with bifascicular block (BFB). Patients with BFB are known to have a higher mortality risk than the general population, not only related to progression to atrio-ventricular block but also due to the presence of malignant ventricular arrhythmias. Previous observational and epidemiological studies including a high proportion of patients with structural heart disease have shown an important cardiac mortality rate and may not reflect the real outcome of patients with BFB. ..................................................................................................................................................................................... Methods From March 1998 until December 2006, we prospectively studied 259 consecutive BFB patients, 213 (82%) of whom and results presenting with syncope/pre-syncope, undergoing electrophysiological study. After a median follow-up of 4.5 years (P25:2.16– P75:6.41), 53 patients (20.1%) died, 19 (7%) of whom due to cardiac aetiology. Independent total mortality predictors were age [hazard ratio (HR) 1.04, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.01–1.09], NYHA class II (HR 2.17, 95% CI 1.05 –4.5), atrial fibrillation (HR 2.96, 95% CI 1.1 –7.92), and renal dysfunction (HR 4.26, 95% CI 2.04–9.01). An NYHA class of II (HR 5.45, 95% CI 2.01–14.82) and renal failure (HR 3.82, 95% CI 1.21–12.06) were independent predictors of cardiac mortality. No independent predictors of arrhythmic death were found. ..................................................................................................................................................................................... Conclusion Total mortality, especially of cardiac cause, is lower than previously described in BFB patients. Advanced NYHA class and renal failure are predictors of cardiac mortality. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Keywords Mortality † Bifascicular block † Electrophysiological study Introduction Chronic bifascicular block (BFB) defined as left bundle branch block (LBBB) or right bundle branch block (RBBB) associated either with a left anterior fascicular block (LAFB) or left posterior fascicular block (LPFB) is a particular form of intraventricular conduction delay. The estimated prevalence in an adult non-selected population is 1–1.5%,1 and the mortality rate ranges 2–14%.2 This mortality rate is higher than in an age- and sex-matched population without BFB in the Framingham study.3 However several epidemiological studies have shown a similar longevity for patients with or without bundle branch block.4,5 However in observational studies, BFB patients with syncope, especially in the setting of structural heart disease and low left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), showed a higher mortality rate, ranging 29 –38%.2,6,7 In these patients, pacemaker implantation prevents death for advanced atrio-ventricular block,8 but this therapy does not improve survival and neither decreases the incidence of sudden cardiac death (SCD) that ranges 14–42%.7,9 – 11 These findings suggest that the poor long-term prognosis in BFB patients may be partially related to an increased risk of malignant ventricular arrhythmias in the setting of a severely impaired conduction system, especially in the presence of severe ventricular dysfunction. The discrepancy between epidemiological and observational studies may be explained by a higher proportion of patients with structural heart disease and low LVEF in those series reporting a high cardiac mortality rate, including SCD,9,10,12 and also by the fact that most of these studies were carried out in the 1980s, when the treatment of structural heart disease was quite different from that employed currently, and could not represent a majority of patients with BFB nowadays. * Corresponding author. Tel: þ34 932483489, Fax: þ34 932483489, Email: [email protected] Published on behalf of the European Society of Cardiology. All rights reserved. & The Author 2009. For permissions please email: [email protected]. Downloaded from europace.oxfordjournals.org by guest on December 3, 2010 Aims 1202 The purpose of the present study is to describe the clinical characteristics and outcome of a cohort of patients with BFB undergoing an electrophysiological study (EPS), in order to ascertain the total, cardiac, and arrhythmic mortality rate and to identify their independent risk factors in a long-term follow-up period. Methods Patient population Electrophysiological study The EPS was performed in the fasting and unsedated state, after withdrawal of all anti-arrhythmic medication for at least five or more half-lives. Two tetrapolar 6 French catheters with a 5 mm interelectrode distance were inserted percutaneously under local anaesthesia through the femoral vein and positioned in the high right atrium (and subsequently moved to the right ventricular apex for ventricular stimulation when considered necessary) and the His bundle region. Our study protocol included assessment of the basal conduction intervals and refractory periods, as described elsewhere.8 Programmed ventricular stimulation was performed in all patients from the apex and the outflow tract of the right ventricle with up to three extra stimuli; minimal coupling interval was 200 ms, and basic drive pacing was performed at cycle lengths of 600, 500, and 430 ms. The endpoint of ventricular stimulation was induction of monomorphic ventricular tachycardia (VT) or sustained ventricular arrhythmia requiring electrical cardioversion. Stimuli were delivered at twice the diastolic threshold with a pulse width of 2 ms using the universal programmable stimulator (Biotronik Inc., Berlin, Germany). The intracardiac and surface ECG (leads V1, V6, I, and III) were recorded on a laboratory system duo (Bard Inc., Boston, USA), at a paper speed of 100 mm/s. The EPS was considered positive for diagnostic of conduction disturbance when the HV interval was 70 ms in symptomatic patients or 100 ms in asymptomatic patients either at baseline or after pharmacological stress-testing with ajmaline (1 mg/kg) or procainamide (10 mg/kg) and also if infra-Hisian block was detected during rapid atrial pacing from 500 ms to the Wenckebach cycle length. The EPS was also considered positive if sustained ventricular arrhythmias able to reproduce clinical symptoms were induced. Treatment and follow-up Symptomatic patients with a positive result on the EPS were treated with pacemaker or an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) as appropriate, according to the guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology.15 All patients were followed up at the outpatient’s clinic 3, 6, 12, and 24 months after EPS. Patients with a pacemaker were followed up at least once a year for life. Patients with an ICD were controlled at least every 6 months for life. In patients with a negative EPS, a tilt test was performed according to the Italian protocol16 and/or a loop recorder inserted to ascertain the cause of syncope. Asymptomatic patients were followed up once a year for 2 years and then referred to the general practitioner. In March 2007, all patients received a telephone call in order to check for life status, syncope recurrences, and hospitalization for any reason. If the patient was dead, the cause was investigated by the hospital records department or by the General Mortality Registry of Catalonia, Spain. Statistical analysis Continuous data with a normal distribution are presented with mean and standard deviation. Those with a not-normal distribution are expressed as median with 25th and 75th percentile. Categorical data are presented as percentages. We analysed three separated models of mortality: total, cardiac, and arrhythmic mortality. For each model, clinical characteristics, ECG, and EPS results were compared by using Student’s t-test or ANOVA for Gaussian variables and by the Mann– Whitney or Kruskal– Wallis test for non-Gaussian variables. Differences in proportions were compared by a x2 analysis or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. We assessed the relationship between clinical characteristics, ECG disturbances, and EPS results for each of the three mortality outcomes, by using a univariate Cox proportional hazards survival model. The multivariate Cox model included all variables that achieved at least marginal significance (P-value ,0.1) as predictors in each model of mortality in the univariate analysis. Those variables for which their exclusion did not change significantly the likelihood of the model and did not change .15% the estimates of the remainder variables were removed of the model. First-order interactions were also Downloaded from europace.oxfordjournals.org by guest on December 3, 2010 Between March 1998 and December 2006, 284 consecutive patients with chronic BFB underwent EPS and were prospectively included and analysed. The LBBB and RBBB patterns were diagnosed according to standard definition.13 Left anterior fascicular block was defined as a mean frontal QRS axis less than 2308 and LPFB as a mean frontal QRS axis .908 in the absence of ECG criteria for right ventricular hypertrophy. The study population was divided into patients with syncope/presyncope (‘symptomatic’ group) or other symptoms/no symptoms (‘asymptomatic’ group). Syncope was defined as complete loss of consciousness with a loss of postural tone with spontaneous and quick recovery. Pre-syncope was defined as a near-syncope situation but without complete loss of consciousness. Patients with advanced congestive heart failure (NYHA class IV), candidates for resynchronization therapy, those with life expectancy under 1 year, those who did not give the informed consent, and those with unspecific conduction delay disturbance not accomplishing ECG criteria for either LBBB or RBBB were excluded. Additionally, patients with an incomplete clinical follow-up were also excluded. The study protocol was explained in detail to each patient before inclusion, and signed informed consent was obtained. Before EPS was performed, all patients were carefully interviewed, with special emphasis on the presence/absence of dyslipaemia, hypertension, diabetes, smoking history, and previous or present cardiac disease. Ischaemic cardiomyopathy was defined as a 70% stenosis of one or more epicardial coronary vessels as documented by angiography in patients with impaired systolic function. These variables were confirmed when the patient received treatment for each of them and considered potential risk factors. Smoking was considered a risk factor when a patient was an active smoker at inclusion. The severity of congestive heart failure was assessed by the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification, and class II or III was considered a potential risk factor. Careful physical examination including carotid sinus massage (in the symptomatic group), routine laboratory tests, and a Doppler echocardiography to characterize structural heart disease were also performed. Renal function was evaluated by estimation of glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) using the Modification on Diet on Renal Disease equation14 (http://nephron.org/cgi-bin/ MDRD_GFR/cgi). Renal failure was divided into mild failure (eGFR 40 – 59 mL/min/1.73 m2) and severe failure (eGFR ,40 mL/min/ 1.73 m2). Under 35% LVEF assessed by echocardiography (Simpson’s rule) was defined as a potential risk factor. The QRS width and the PR interval in the 12-lead ECG were also assessed. J. Marti-Almor et al. 1203 Mortality predictors in chronic bifascicular block tested. Results are expressed in hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Kaplan– Meier survival curves with log-rank test evaluated univariate associations between clinical events and each kind of mortality. Results Electrophysiological study In 162 patients (63%), the EPS was positive either for the diagnosis of conduction disturbances (158 patients) or for VT induction (6 patients). Of note, VT inducibility was not associated with a higher mortality of any kind (Table 2). An ICD was implanted in seven patients: six inducible patients and one non-inducible patient by fulfilling the MADIT II criteria. All inducible patients had structural heart disease (ischaemic aetiology in five and Table 1 Total mortality descriptive analysis Variables Total (n 5 259) Alive (n 5 206) Dead (n 5 53) Male, n (%) 176 (68) 139 (67) 37 (69) 0.93 Age ( mean + SD) Syncope/pre-syncope, n (%) 73 + 9 213 (82) 72 + 9 168 (82) 75 + 9 45 (83) 0.08 0.85 P-value ............................................................................................................................................................................... NYHA .II, n (%) 60 (23) 39 (19) 21 (40) 0.002 Structural heart disease, n (%) Hypertension, n (%) 122 (47) 172 (66) 87 (42) 134 (65) 35 (65) 38 (71) 0.004 0.46 Diabetes, n (%) 77 (30) 60 (29) 17 (32) 0.69 Dyslipaemia, n (%) Active smoker, n (%) 77 (30) 29 (11) 64 (31) 24 (12) 13 (24) 5 (9) 0.35 0.79 LVEF,35%, n (%) 30 (12) 19 (9) 11 (20) 0.01 Renal function eGFR 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 151 (58) 130 (63) 21 (40) 83 (32) 64 (31) 18 (34) 26 (10) 12 (6) 14 (26) eGFR 40– 59 mL/min/1.73 m2 eGFR ,40 mL/min/1.73 m2 ECG ,0.001 Atrial fibrillation, n (%) 12 (5) 6 (3) 6 (11) 0.02 PR interval .200 ms, n (%) QRS width, ms 128 (49) 144.6 + 15.1 101 (48) 143.9 + 14.6 27 (50) 146.1 + 17.0 0.84 0.36 LAFB þ RBBB, n (%) LPFB þ RBBB, n (%) 131 (50) 22 (8) 101 (48) 19 (9) 30 (56) 3 (6) LBBB, n (%) 106 (40) 86 (41) 20 (37) 0.53 158 (61) 121 (59) 37 (70) 0.36 6 (2) 4 (2) 2 (4) 0.61 Kind of BFB EPS HV interval .70 ms, n (%) VT inducibility, n (%) NYHA, New York Heart Association functional class; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; BFB, bifascicular block; LBBB, left bundle branch block; RBBB, right bundle branch block; LAFB, left anterior fascicular block; LPFB, left posterior fascicular block; eGFR, estimation of glomerular filtration rate; VT, ventricular tachycardia. Downloaded from europace.oxfordjournals.org by guest on December 3, 2010 Twenty-five of the initial 284 patients were excluded from analysis due to incomplete clinical information or unspecific ECG conduction delay. Of the remaining 259 patients, 213 (82%) were studied for syncope or pre-syncope, and 46 patients were asymptomatic. The symptomatic group included 172 patients with syncope and 41 with pre-syncope, without baseline clinical differences between them. The asymptomatic group included 22 BFB patients undergoing catheter ablation of supraventricular tachycardia and an additional 24 patients with BFB undergoing EPS for preoperative risk evaluation, due to the presence of severe conduction disturbances. The clinical characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. The predominant structural heart disease was ischaemic and hypertensive cardiomyopathy (46 patients each), followed by dilated cardiomyopathy (20), valvular heart disease (10), and 1 single case of obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Median LVEF of this subgroup was 53% (P25:39–P75:59). The QRS duration in symptomatic patients was significantly shorter [140 (131 –148) ms] as opposed to the asymptomatic group [152 (148–168) ms; P ¼ 0.016]. Similarly, the PR interval was 290 (220– 372) ms in the asymptomatic, as opposed to 215 (186 –249) ms in the symptomatic group (P ¼ 0.006). In the whole group, the median LVEF was 63% (P25:54 –P75:66), and in 30 patients (12%), it was ,35%. Sixty patients (23%) were in NYHA class II or higher. Patients were under statins, ACE-inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and beta-blockers in 28, 41, 19, and 12%, respectively. There were no differences in the beta-blockers intake between symptomatic (24/217) and asymptomatic (8/46) patients. 1204 J. Marti-Almor et al. Table 2 Hazard ratio for total and cardiac mortality during the follow-up using bivariate Cox models Variables Total mortality (n 5 53) Cardiac mortality (n 5 19) Male 1.03 (0.58–1.84) 1.04 (0.39– 2.74) Age Syncope/pre-syncope 1.04 (1.01–1.08) 1.08 (0.52–2.21) 1.0 (0.95–1.05) 1.86 (0.43– 8.05) ............................................................................................................................................................................... NYHA .II 3.13 (1.79–5.51) 6.93 (2.69– 17.87) Structural heart disease Hypertension 2.3 (1.31– 4.04) 1.33 (0.74–2,39) 4.45 (1.47– 13.42) 2.94 (0.85– 10.13) Diabetes 1.16 (0.64–2.08) 1.49 (0.58– 3.81) Dyslipaemia Active smoker 0.77 (0.41–1.47) 1.09 (0.64–1.87) 0.66 (0.22– 2.01) 1.06 (0.43– 2.62) LVEF ,35% 2.95 (1.5– 5.78) 4.75 (1.77– 12.74) Renal function eGFR 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 Reference eGFR 40–59 mL/min/1.73 m2 Atrial fibrillation PR interval .200 ms Kind of BFB 1.46 (0.78–2.75) 1.46 (0.49– 4.35) 5.06 (2.54–10.1) 5.82(1.93–17.52) 2.77 (1.18–6.51) 0.05 (indeterminate) 1.35 (0.75–2.42) 1.48 (0.59– 3.72) LAFBþRBBB Reference LPFBþRBBB LBBB 0.46 (0.14–1.53) 0.9 (0.51– 1.61) 0.46 (0.06– 3.6) 1.08 (0.42– 2.76) 0.95(0.53– 1.69) 2.07 (0.50–8.54) 1.06 (0.42– 2.71) 3.18 (0.42– 24.05) EPS HV interval .70 ms VT inducibility NYHA, New York Heart Association functional class; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; BFB, bifascicular block; LBBB, left bundle branch block; RBBB, right bundle branch block; LAFB, left anterior fascicular block; LPFB, left posterior fascicular block; eGFR, estimation of glomerular filtration rate; VT, ventricular tachycardia. dilated cardiomyopathy in one) and LVEF ,35%. Six patients presented with appropriate shock ICD therapies during follow-up (five inducible and one non-inducible). In 156 patients, a pacemaker was implanted, and in the follow-up, 102 patients used the pacemaker for progression to atrio-ventricular block. Total mortality After a median follow-up period of 4.5 (P25:2.16–P75:6.41) years, 53 (20.1%) patients died. There were no differences between syncope and pre-syncope patients. Cardiac aetiology was the cause of death in 19 patients (7%). Of the 34 (13%) patients with a non-cardiac death, 15 died from cancer and 19 due to a concomitant illness such as pneumonia in 5, stroke in 4, cirrhosis in 3, hip fracture in 3, sepsis of abdominal origin in 2, diabetic cetoacidosis in 1, and aplastic anaemia in 1. The 2 year and 5 year cumulative survival rate was 94 and 79%, respectively (Figure 1). The analysis of clinical, electrocardiographic, and electrophysiological BFB patient characteristics identified the following predictors of total mortality (Table 1): An NYHA II (40% of deaths vs. 19% of survivors; P ¼ 0.002), structural heart disease (65 vs. 42%, respectively; P ¼ 0.004), an ejection fraction ,35% (20 vs. 9%, respectively; P ¼ 0.01), renal failure with an eGFR Figure 1 Kaplan– Meier survival curves for total and cardiac mortality. Total mortality was mainly due to non-cardiac aetiology. The 2 year total mortality rate was 6%. ,40 mL/min/1.73 m2 (26 vs. 6%, respectively; P , 0.001), and atrial fibrillation (11 vs. 3%, respectively; P ¼ 0.02). The total, cardiac, and arrhythmic mortality were not influenced by the BFB type (Tables 1 and 2). Of note, an HV interval .70 ms was not associated with an increased total mortality (Table 1). In six patients, an HV interval 100 ms was observed at baseline, Downloaded from europace.oxfordjournals.org by guest on December 3, 2010 eGFR ,40 mL/min/1.73 m2 ECG 1205 Mortality predictors in chronic bifascicular block Table 3 Hazard ratio for total and cardiac mortality and for the presence of ventricular arrhythmias during the follow-up using multivariate Cox models Variable HR 95% IC P-value ................................................................................ Total mortality Age 1.04 1.01–1.09 0.02 Atrial fibrillation eGFR ,40 mL/min/1.73 m2 2.96 4.29 1.10–7.92 2.04–9.01 0.03 ,0.001 NYHA II 2.17 1.05–4.52 0.03 2.41 0.99–5.84 0.05 NYHA II 5.45 2.01–14.82 0.001 eGFR ,40 mL/min/1.73 m2 3.82 1.21–12.06 0.02 LVEF ,35% Cardiac mortality and in six additional patients, the administration of infra-His-stressing drugs induced an HV interval 100 ms. No differences in mortality were observed in this subset of patients. Bivariate Cox regression analysis confirmed that the variables implicated in the total mortality were atrial fibrillation, eGFR ,40 mL/min/1.73m2, NYHA II, structural heart disease, ejection fraction ,35%, and age (Table 2). The aforementioned univariate associations were tested in the multivariate Cox model. This model showed that age, NYHA II, atrial fibrillation, and eGFR ,40 mL/min/1.73 m2 were independent predictive factors for total mortality. Nevertheless, LVEF ,35% was marginally significant (Table 3). Cardiac mortality In our series, 19 (7%) patients died from cardiac causes, 6 of whom due to SCD, 11 from heart failure progression, and 2 from fatal myocardial infarction. The descriptive analysis showed that the variables related to cardiac mortality were the following: an NYHA II (58% of cardiac deaths when compared with 21% in the survivors, P , 0.001), structural heart disease (79 vs. 45%, respectively; P ¼ 0.004), LVEF ,35% (33 vs. 10%, respectively; P ¼ 0.01), and renal failure with eGFR ,40 mL/min/1.73 m2 (42 vs. 15%, respectively; P ¼ 0.02). Hypertension showed only marginal statistical significance. In the bivariate Cox regression analysis, the variables that showed an increased risk for cardiac mortality were an NYHA II (P 0.001), an LVEF ,35% (P ¼ 0.007), structural heart disease (P ¼ 0.01), and eGFR ,40 mL/min/1.73 m2 (P ¼ 0.01), as shown in Table 2. Multivariate Cox regression analysis demonstrated that only advanced NYHA class and depressed eGFR increased the risk for cardiac mortality (Table 3). Arrhythmic mortality Six patients (2.3%) died from SCD. In only two of them, ventricular fibrillation was the first rhythm detected by an emergency care unit. The rest were possibly due to arrhythmic origin but Discussion The main finding in our study is a lower total mortality rate (20.1% in a median follow-up of 4.5 years) than expected in comparison with previous studies, mainly due to lower cardiac and sudden death mortality rates in our BFB population. Dhingra et al.17 analysed 517 patients with BFB, and a total mortality of 38% was determined after a 7 year follow-up period, with SCD being mainly responsible for this mortality rate. In addition, McAnulty et al.7 established a total mortality rate among BFB patients of 29%, 42% of which due to SCD. These discrepancies could be related to a higher percentage of patients with structural heart disease and lower LVEF in these previous studies. Moreover, drugs such as ACE-inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, betablockers, or statins, with proven survival benefits, were less frequently administered when these studies were published than currently. Finally, whether a higher proportion of BFB patients undergoing pacemaker implantation in our population may have lowered the mortality rate is not clear. In more recent studies, Tabrizi et al.11 analysed 100 patients with BFB, reporting a mortality rate of 33%, half of them due to SCD. In this study, 57% of patients had structural heart disease, with a mean LVEF of 46%, and in 23% of them, the LVEF was ,35%. In contrast, in our study, only 47% of patients had structural heart disease, with median LVEF of 63% and only 12% of patients with a severe left ventricular dysfunction (LVEF ,35%). Furthermore, in Tabrizi et al.’s study, the proportion of patients treated with ACE-inhibitors (27%) was much lower than in our study (41%), with a similar rate of beta-blockers intake. Importantly, the outcomes of our patient population are in agreement with the B4-Study (Bradyarrhythmia Bundle Branch Block Study).18 In this study of more than 400 patients with chronic BFB (mainly LBBB), a similar total mortality rate of 5.7% is described in a 18-month follow-up period (2 year total mortality rate of 6% in our series). The clinical characteristics of the B4-Study population, including a mean LVEF of 56 + 12% and 50% of structural heart disease, were similar to our study (median of LVEF of 63% and structural heart disease present in 47% patients). We believe our study accurately represents the current characteristics and clinical outcomes of patients with BFB, especially those who are symptomatic for syncope or pre-syncope. Predictors of mortality in bifascicular block patients In the present study, an advanced NYHA functional class is associated with any kind of mortality. There is considerable evidence supporting that patients with heart failure have a higher mortality rate when conduction delay disorders are present. In the MADIT II trial, which included more than half of patients with NYHA II, a higher total and cardiac mortality rates were observed in patients with intraventricular conduction delay, when compared with patients with narrow QRS.19 Additional studies have Downloaded from europace.oxfordjournals.org by guest on December 3, 2010 eGFR, estimation of glomerular filtration rate; NYHA, New York Heart Association functional class; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction. unwitnessed. No independent predictor for this kind of mortality was found. 1206 Study limitations In this analysis, a comparative age- and sex-matched group of patients without BFB was not used. Nevertheless, the mortality rate in our study is lower than previously described and is essentially related to non-cardiac death. We believe that the use of a comparative group would have not changed our results. A relatively short-term follow-up in our series may also account for the low mortality rate observed. However, previous series with even shorter follow-up periods have shown higher mortality rates than in the present study. It is unclear whether a larger number of patients would have influenced the mortality results in our series. The small number of patients with unspecific EGC conduction delay (only four patients) did not allow us to establish the long-term outcome of this subset of patients. Bifascicular block patients with low ejection fraction and structural heart disease may not be sufficiently represented in our study and might have changed the results obtained. We included 24 asymptomatic patients for surgery risk evaluation, and this subgroup, although asymptomatic, had a more extensive conduction disorder. However, we believe that this selection bias has not affected the final results of the study. Conclusions In this study, the total and especially cardiac mortality rates are lower than previously reported. A different drug strategy including ACE-inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, beta blockers, or statins, and the fact of including a relatively healthy population may have changed the natural history of patients with chronic BFB. An advanced NYHA class and the presence of renal failure are independent predictors of total and cardiac mortality in patients with chronic BFB. Conflict of interest: none declared. References 1. Scheinman MM, Peters RW, Morady F, Sauve MJ, Malone P, Modin G. Electrophysiologic studies in patients with bundle branch block. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1983;6:1157 –65. 2. McAnulty JH, Kauffman S, Murphy E, Kassebaum DG, Rahimtoola SH. Survival in patients with intraventricular conduction defects. Arch Intern Med 1978;138:30 –5. 3. Schneider JF, Thomas HE Jr, Sorlie P, Kreger BE, McNamara PM, Kannel WB. Comparative features of newly acquired left and right bundle branch block in the general population: the Framingham study. Am J Cardiol 1981;47:931 –40. 4. Fahy GJ, Pinski SL, Miller DP, McCabe N, Pye C, Walsh MJ et al. Natural history of isolated bundle branch block. Am J Cardiol 1996;77:1185 –90. 5. Smith S, Hayes WL. The prognosis of complete left bundle branch block. Am Heart J 1965;70:157 –9. 6. Dhingra RC, Denes P, Wu D, Chuquimia R, Amat-y-Leon F, Wyndham C et al. Syncope in patients with chronic bifascicular block. Significance, causative mechanisms, and clinical implications. Ann Intern Med 1974;81:302 –6. 7. McAnulty JH, Rahimtoola SH, Murphy E, DeMots H, Ritzmann L, Kanarek PE et al. Natural history of ‘high-risk’ bundle-branch block: final report of a prospective study. N Engl J Med 1982;307:137 –43. 8. Scheinman MM, Peters RW, Suave MJ, Desai J, Abbott JA, Cogan J et al. Value of the H-Q interval in patients with bundle branch block and the role of prophylactic permanent pacing. Am J Cardiol 1982;50:1316 –22. 9. McAnulty JH, Rahimtoola SH, Murphy ES, Kauffman S, Ritzmann LW, Kanarek P et al. A prospective study of sudden death in ‘high-risk’ bundle-branch block. N Engl J Med 1978;299:209–15. 10. Denes P, Dhingra RC, Wu D, Wyndham CR, Amat-y-Leon F, Rosen KM. Sudden death in patients with chronic bifascicular block. Arch Intern Med 1977;137: 1005 –10. 11. Tabrizi F, Rosenqvist M, Bergfeldt L, Englund A. Long-term prognosis in patients with bifascicular block—the predictive value of noninvasive and invasive assessment. J Intern Med 2006;260:31 –8. Downloaded from europace.oxfordjournals.org by guest on December 3, 2010 underlined that heart failure patients with intraventricular conduction delay and/or QRS widening have an increased mortality rate.20,21 In our study, the documentation of atrial fibrillation was associated with a higher total mortality rate. These results are in accordance with previous evidence of a higher mortality rate in patients with atrial fibrillation, not exclusively due to a higher number of stroke events.22 Surprisingly, in our series, atrial fibrillation increases the total mortality but not the cardiac mortality. Whether this incongruence accounts for the low number of atrial fibrillation patients in our population is not clear. It is generally accepted that an LVEF ,35% is clearly linked to a higher mortality rate associated with SCD or progression of heart failure.20 In our study, the survival rate of patients with low LVEF after a 5 year follow-up was 50% in comparison with 84% in patients with LVEF .35%, with a cardiac mortality rate of 33 and 10%, respectively, P ¼ 0.01. However, in the multivariate Cox regression analysis for total mortality, LVEF ,35% was not statistically significant (HR 2.4, 95% CI 0.99–5.8). This result can be explained by the low proportion of patients with depressed LVEF in our study. More than half of cardiac deaths in our population were due to heart failure. In this group (10 patients), the LVEF was not inferior to the LVEF of patients who died from other cardiac causes (41 vs. 44%, respectively). Noteworthy, seven of these patients had advanced atrio-ventricular block in the follow-up. Evolution to terminal heart failure could have been facilitated by permanent right ventricular apex stimulation in this subgroup, as supported by previous evidence in BFB patients.21,23,24 According to previous studies,25,26 renal failure increases total mortality and cardiac mortality in patients with BFB (39 vs. 11% of total mortality; P , 0.001, and 42 vs. 15% of cardiac mortality; P ¼ 0.02, compared with normal renal function patients, respectively). Induction of sustained monomorphic VT in the EPS is lower than in previous studies in patients with BBF and syncope,27,28 probably due to a relatively healthy population included in our study. Clinical arrhythmic events during follow-up may not be predicted by inducibility either in symptomatic or in asymptomatic patients.29 In fact, we were not able to demonstrate a relationship between VT inducibility and arrhythmic mortality, in accordance with previous evidence.30 In the MADIT II trial, among the 593 patients who underwent EPS, no statistical differences in appropriate therapies between inducible and non-inducible patients were found.31 Importantly, the absence of VT inducibility in our population was associated with an excellent outcome, with no ventricular arrhythmia documentation during follow-up, except for a single patient. It is suggested by this study that a strict control of the renal function, atrial fibrillation, and NYHA class might have an influence in the prevention of total mortality in patients with BFB. In BFB patients, an EPS may be indicated for the assessment of progression to advanced AV block, but not for mortality prediction, especially in the setting of relatively healthy patients. J. Marti-Almor et al. Mortality predictors in chronic bifascicular block 23. Lamas GA, Lee KL, Sweeney MO, Silverman R, Leon A, Yee R et al. Ventricular pacing or dual-chamber pacing for sinus-node dysfunction. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:1854 –62. 24. Sweeney MO, Hellkamp AS, Lee KL, Lamas GA. Association of prolonged QRS duration with death in a clinical trial of pacemaker therapy for sinus node dysfunction. Circulation 2005;111:2418 –23. 25. Chonchol M, Goldenberg I, Moss AJ, McNitt S, Cheung AK. Risk factors for sudden cardiac death in patients with chronic renal insufficiency and left ventricular dysfunction. Am J Nephrol 2007;27:7 –14. 26. Goldenberg I, Moss AJ, McNitt S, Zareba W, Andrews ML, Hall WJ et al. Relations among renal function, risk of sudden cardiac death, and benefit of the implanted cardiac defibrillator in patients with ischemic left ventricular dysfunction. Am J Cardiol 2006;98:485 –90. 27. Click RL, Gersh BJ, Sugrue DD, Holmes DR Jr, Wood DL, Osborn MJ et al. Role of invasive electrophysiologic testing in patients with symptomatic bundle branch block. Am J Cardiol 1987;59:817 –23. 28. Ezri M, Lerman BB, Marchlinski FE, Buxton AE, Josephson ME. Electrophysiologic evaluation of syncope in patients with bifascicular block. Am Heart J 1983;106: 693 –7. 29. Englund A, Bergfeldt L, Rehnqvist N, Astrom H, Rosenqvist M. Diagnostic value of programmed ventricular stimulation in patients with bifascicular block: a prospective study of patients with and without syncope. J Am Coll Cardiol 1995;26: 1508 –15. 30. Buxton AE, Lee KL, DiCarlo L, Gold MR, Greer GS, Prystowsky EN et al. Electrophysiologic testing to identify patients with coronary artery disease who are at risk for sudden death. Multicenter Unsustained Tachycardia Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1937 –45. 31. Daubert JP, Zareba W, Hall WJ, Schuger C, Corsello A, Leon AR et al. Predictive value of ventricular arrhythmia inducibility for subsequent ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation in Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial (MADIT) II patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:98–107. Downloaded from europace.oxfordjournals.org by guest on December 3, 2010 12. Dhingra RC, Wyndham C, Bauernfeind R, Denes P, Wu D, Swiryn S et al. Significance of chronic bifascicular block without apparent organic heart disease. Circulation 1979;60:33 –9. 13. Criteria Committee of the New York Heart Association. Nomenclature and Criteria for Diagnosis of Diseases of the Heart and Great Vessels. Boston: Little, Brown; 1973. p238 – 9. 14. Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, Stevens LA, Zhang YL, Hendriksen S et al. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 2006; 145:247 –54. 15. Brignole M, Alboni P, Benditt DG, Bergfeldt L, Blanc JJ, Thomsen PE et al. Guidelines on management (diagnosis and treatment) of syncope—update 2004. Executive Summary. Eur Heart J 2004;25:2054 – 72. 16. Bartoletti A, Alboni P, Ammirati F, Brignole M, Del Rosso A, Foglia Manzillo G et al. ‘The Italian Protocol’: a simplified head-up tilt testing potentiated with oral nitroglycerin to assess patients with unexplained syncope. Europace 2000;2:339–42. 17. Dhingra RC, Palileo E, Strasberg B, Swiryn S, Bauernfeind RA, Wyndham CR et al. Significance of the HV interval in 517 patients with chronic bifascicular block. Circulation 1981;64:1265 –71. 18. Moya A, Garcia-Civera R, Brugada J, Croci F, Menozzi C, Ammirati F et al. The management of syncope in patients with bundle branch block: a multicenter prospective study. Europace 2008;10 (Suppl. 10):i 44. 19. Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, Klein H, Wilber DJ, Cannom DS et al. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2002;346:877–83. 20. Rosanio S, Schwarz ER, Vitarelli A, Zarraga IG, Kunapuli S, Ware DL et al. Sudden death prophylaxis in heart failure. Int J Cardiol 2007;119:291 – 6. 21. Sharma AD, Rizo-Patron C, Hallstrom AP, O’Neill GP, Rothbart S, Martins JB et al. Percent right ventricular pacing predicts outcomes in the DAVID trial. Heart Rhythm 2005;2:830 – 4. 22. Friberg L, Hammar N, Pettersson H, Rosenqvist M. Increased mortality in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: report from the Stockholm Cohort-Study of Atrial Fibrillation (SCAF). Eur Heart J 2007;28:2346 –53. 1207